1. Introduction

The benefits of a co-production of knowledge with indigenous communities through participatory research methods that respect their priorities, beliefs, and worldviews and empower communities in the process of addressing conservation challenges are now widely recognised and advocated by many researchers [

1,

2]. Art-based research is a growing new field, which is defined as the inclusion of creative arts in research methods [

3,

4]. This can be done during any or all phases, such as in data generation, analysis, interpretation, and/or representation of results. The integration of art in participatory environmental research specifically is also now an emerging and growing field with the potential to deliver numerous benefits to biodiversity conservation [

5]. This is because art can evoke emotions, cultivate empathy, capture the multi-sensorial nature of lived experience, and promote self-reflection and consciousness about complex environmental changes [

3,

6]. Through art, researchers can identify different perceptions, emotions, and social values related to nature, which are often overlooked by traditional research and that unavoidably influence conservation efforts [

5,

7]. Art also offers unique ways to build bridges between indigenous knowledge and other types of knowledge, enriching the possibilities for genuine knowledge co-production and the stimulation of critical thinking [

7,

8]. For example, visual arts offer powerful resources for communicating complex science in understandable ways [

9]. Visual arts have also shown a great capacity to foster creative solutions to complex problems, and this capacity is increased when solutions are discussed in groups [

10]. Collective artworks have proved to be particularly useful vectors to express opinions and reflect on common resources and identities (such as the meaning of environmental resources and territory), able to incite a sense of place and increase the motivation to care for them [

11]. In addition, the use of art in environmental research has been documented to be a powerful tool to decrease the distance between researchers and other stakeholders, empower all participants, enhance conversations in creative, harmonious, and inclusive ways and foster reflections towards transformative actions for biodiversity conservation [

5].

In our study, we aimed to understand the challenges facing the conservation of maize biodiversity in Mexico as perceived by indigenous farming communities and to advance the co-creation of shared solutions to these challenges based on their own hopes and agency for action. Thus art-based methods emerged as potentially useful to our purposes. However, the majority of art-based research projects that we were aware of tended to involve the participation of artists and/or art expertise [

3,

9,

11,

12,

13]. Despite the significant benefits that bringing artists and scientists together can have, in this case, our purpose was to diminish as much as possible the intervention of external influences on the community and the establishment of hierarchies of expertise, allowing participants to define their own problems and strategies for change. We wanted a method that would be able to empower community participants to express their experiences and emotions, minimise bias toward literacy as a requirement for participation, and actively help to acknowledge and capture the importance of culture in agricultural practice [

3,

6,

13,

14].

In our search for such a method, we were particularly drawn to an art-based method known as Photovoice [

15]. Photovoice was originally articulated for participatory needs assessment in the area of public health and is described as a method that aims to “enable people to record and reflect their community’s strengths and concerns” [

15]. Thus, Photovoice’s main goals are to give voice to marginalized people by exploring their perceptions and emotions on a topic, to empower participants by recognizing their knowledge and expertise, and to stimulate reflections that highlight participants’ own responsibilities, strengths, and resources in a non-hierarchical way. All of this is designed to promote and facilitate transformative action for social and environmental change and justice [

16,

17].

Photovoice has received increased uptake in recent years and has been used as a method in the fields of public health [

18,

19,

20] psychology [

21], education [

22], and social science [

23]. It has also been implemented to a lesser extent, although with positive outcomes, in community-based environmental and indigenous studies research [

17,

24]. For example, Thompson [

25] found in Photovoice a useful way to raise the voices of young farmers from Sierra Leone on their needs and relationship to the environment after civil war. Bennett and Dearden [

26] also used Photovoice as a means to reflect on socio-ecological changes and their impacts on natural resources management and climate change adaptation in Thailand.

However, practitioners using this method have also noticed some limitations and have modified Photovoice with aims to increase its beneficial outcomes. Castleden and Garvin [

27] showed that to encourage participation and include as many voices as possible, they needed to modify the method in terms of its structure and schedule so that it was more flexible in terms of recruitment time, and a training session was replaced by several visits to participants. During these visits, researchers also found an opportunity to perform semi-structured interviews that helped them get more information and a better understanding of individual thoughts and perspectives. Additionally, they could identify priorities that should be included in group discussions. The authors underlined how the extension of the time and visits helped to increase the feeling of trust in the relationship between participants and the research team. They also noted that the traditional way of conducting Photovoice can limit participation from elders, who may have mobility restrictions. Gervais and Rivard [

28] have also created SMART Photovoice, a modified version of Photovoice to work with women farmers in Rwanda in the post-genocide context. They created SMART with the intention of making Photovoice a more context adapted methodology and increasing participants’ involvement in all sections of the research project, thereby promoting participants’ empowerment and ownership over the project. Another adjustment to Photovoice was suggested by Glenis and Boulton [

29], who described the importance of adapting Photovoice to the local culture. They therefore proposed Maori-voice, which includes traditional Maori forms of expression such as storytelling, proverbs, and meaning making in relation to the photos taken. They highlighted how adapting Photovoice to cultural forms is a key for participants’ ownership and feelings of belonging in the research project.

We could clearly see the value of using the Photovoice method. However, we also saw limitations. Although the developers of Photovoice have emphasized that photography is an accessible art form [

15], they also describe the importance of running training workshops with participants. This is so that they both understand the ethical and privacy issues that can arise when taking people’s photo [

30] and to train them in how to use the technology of the camera. For us, these factors seemed to, in an unintentional way, challenge the removal of hierarchical relations since the technical device of the camera required outside expertise from the outset. The method also potentially imposed the use of a particular technical tool for communication that required a reliance on others to process to fruition. This is perhaps particularly the case when cameras and photography are not already an integrated part of the community’s culture. Furthermore, we saw that although photography was an art form that was particularly useful for capturing and communicating present day realities, it was less directly capable of communicating historical relationships and/or presenting future visions and ideals. We considered this restriction to be important since by mentally travelling through time, participants may increase their awareness of the socio-ecological changes that have occurred and discover positive changes that can enhance conservation [

24]. Remembering and retelling history through storytelling helps to recognise traditional indigenous knowledge and promote the intergenerational transfer of knowledge and values. Also, having individual reflections on history can help increase collective reflection when they are discussed with a broader audience that shares the same past [

31]. Given the potential value and benefits of Photovoice though, we chose to address these limitations by modifying and expanding the method to what we called CreativeVoice, which would allow participants to choose whether they would like to use photography or other art forms to present their perspectives and for their artwork and discussions to capture and span different time periods.

The diversity of native maize in Mexico, developed over thousands of years of cultivation and selection, is currently under threat from a range of socio-political and cultural developments. These include the substitution of native by conventional seeds, market changes due to free trade agreements such as NAFTA [

32,

33], conflicting policies on the import and cultivation of genetically modified organisms [

34,

35], and emigration of the labor force provoking abandonment of the land and a set of socio-cultural changes [

36,

37]. In many indigenous communities, modernization, urbanisation, and globalisation have dramatically affected the ability or motivation of farming communities to continue playing the (largely unpaid and unrecognised) role of agrobiodiversity conservationists [

36,

37].

We applied CreativeVoice as a novel approach for local engagement. We were specifically interested in farmers’ perceptions of the challenges that native maize farming is facing in Mexico. We aimed to collect perspectives from participants of different ages and genders in two indigenous farming communities. Since the presence of diverse perspectives can influence the development of shared strategies for action towards native maize conservation, we employed CreativeVoice as a method to stimulate discussion, reveal diverging perspectives and to inspire community members to think creatively about both the challenges they face for continuing maize biodiversity conservation and the solutions they may collectively pursue. We discovered that the co-creation of knowledge between researchers and indigenous communities for advancing sustainability benefits significantly from the type of integration of art and science present in this method and therefore share the CreativeVoice method and our experiences with it in this paper.

2. Locations and Methods

2.1. Locations

We worked with two different indigenous communities in the state of Oaxaca, which is recognised as a center of diversity for maize [

38]. A landrace of maize is a variable population that is locally identifiable, characterized by its adaptation to specific environmental conditions and closely associated with the traditional uses and knowledge of those that have developed it (Negri 2007). The 35 landraces of maize present in Oaxaca represent approximately 70% of the maize richness of the country. The distribution and surface area cultivated with these races depend on the decisions of indigenous farmers’ [

39]. Oaxaca is also known for its great cultural diversity, containing 16 different indigenous peoples, with Zapotec, Mixtec, and Mixe peoples being the largest groups in the state. In Oaxaca, handicrafts and other creative and artistic expressions are also a widespread and important part of the cultural life. Oaxacan people find in the arts means to express their cultural identity, political conflicts and victories, and ecological relationships [

40,

41,

42].

The present study was developed in two contrasting indigenous farming communities, in terms of ethnicity, social organisation, and ecological conditions (

Figure 1).

Nuevo Santiago Tutla (Tutla): Mixe people populate Tutla, which has a community management of the land and every decision is taken collectively in the community assembly. Tutla is located eight hours from Oaxaca City in the Sierra Norte, bordering with Isthmus of Tehuantepec. The main economic activity in the community is agriculture/livestock farming. Community members of Tutla, mainly young members, normally experience temporary national migration to nearby cities for study or temporary jobs. Mixe people are well known for using music as a traditional artistic expression, with their skills for playing wind instruments and their community string orchestras being broadly recognized [

43].

Santiago Apostol (Apostol): Zapotec people populate Apostol. In Apostol, the land is private property, and then there is no legal obligation to ask for collective permission regarding decisions over the land. Apostol is located just an hour’s drive from the capital city of Oaxaca, in the municipality of Ocotlan, in Central Valleys region of Oaxaca. We did not find an official document describing the migration rate of the community; but participants stated that approximately more than 50% of the population has permanently migrated to the United States of America, bringing a constant cultural exchange between migrants and the remaining community members. Zapotec people have previously used a diversity of artistic expressions such as painting, pottery, textiles, woodcarving, music, dance, and more recently graffiti to communicate their perspectives, thoughts, and struggles [

40,

42].

2.2. The CreativeVoice Method

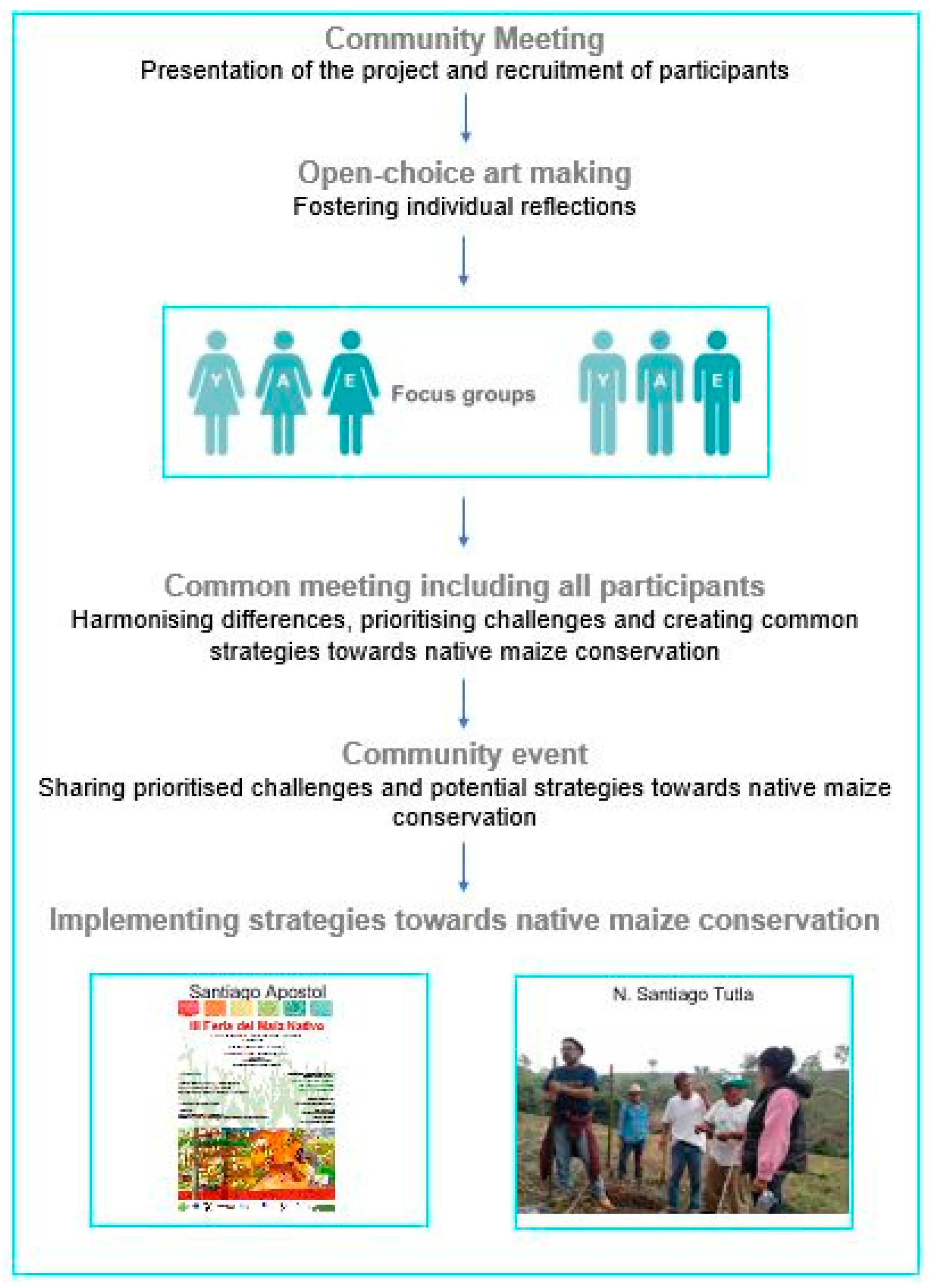

CreativeVoice shares the principles and many of the same steps as Photovoice. However, some amendments were made to overcome some of the limitations described above (

Figure 2).

As a first step, we called for a community meeting to inform the communities about the project and invite members to participate. This meeting aimed to present the objectives of the project, answer questions and clarify any potential doubts participants could have about their involvement. We called for volunteers to join and asked those who registered to give their written consent to participate in the project. This consent included a statement that acknowledged that they would always retain ownership over their artwork and that they had the freedom to leave the project at any time. We soon understood that a community meeting was necessary to inform the community and to introduce our research team, but that we also needed additional efforts to recruit participants and obtain the representation that we wanted. Therefore, visits to individuals identified as potential volunteers by other communitarian members were conducted. These visits were useful to encourage members to participate and gave us the opportunity to get more information on individual perspectives about native maize conservation. They were also a means to develop and increase trust between participants and researchers, particularly in Apostol, to assure them that we wanted a collaboration and not only extraction of their knowledge, as had been previously experienced by the community.

Registered participants were then asked to create artwork to portray their own story and history of native maize in their community. Participants were also particularly encouraged to reflect on the role of native maize and its diversity in their daily lives, changes over time that could influence (negatively or positively) the conservation of native maize biodiversity, and what they would like to do (or not do) to maintain this into the future. Here, the major methodological amendment that we felt was important was to offer participants other forms of artistic expression in addition to photography as a way to communicate their lived experience. We felt that it was particularly important to open up forms of the creative arts that were more commonly used in the participants’ culture and that they may therefore feel more comfortable and capable working with. Since we were specifically aiming to work with elders (50+ years), adults (25–50 years), and adolescents (12–25 years) of both genders, we also felt that it was important not to only offer a single art form that may be more familiar or comfortable for one of these age or gender groups. While we were open to the use of any art form, nevertheless, we found it important to give examples of different types to help communicate the task. We did this by presenting three categories of creative arts: (1) photos/video, (2) poems/stories/songs, and (3) drawings/paintings.

They were then given a month to create their artwork, and any materials they needed were provided by the project. It is important to highlight that the task was not immediately understood and engaged with by all participants. Thus, during this month of artwork creation time, project researchers made visits to the communities to stay in touch with the participants, help clarify the task and check if more materials were required. This follow up was particularly important for the elders participating in the project, who were used to more hierarchical relationships with researchers and therefore hesitated to accept that they were being given an open task with freedom of expression. It was therefore of great importance in the early stages that the researchers were able to carefully clarify the doubts participants had about what was being asked of them without solving or overly framing the task for them. Without doing this with care, there was the possibility of perpetuating hierarchical relationships between researchers and participants and the risk of having perspectives biased through the influence of the researcher. Striking this balance between having a frame for the task and the project but allowing freedom for the participants to come with their own problem formulations and forms of expression was one of the ongoing learning challenges associated with applying this method.

After the creation of their artwork, just as in Photovoice, participants were invited to bring them to small focus group discussions. These small focus groups were initially divided by gender and age, which helped us to minimize potential power imbalances among men and women as well as among elders and youth and effectively allowed us to first collect the perspectives of the different social groups in isolation. Other imbalances generated by the social and political status of participants could not be avoided in the focus groups, but were tackled through inclusive facilitation techniques, encouraging the expression of all voices and giving the same value to all interventions. The participants in each focus group discussion shared their motivations for creating their particular artwork and talked about what it represented for them in terms of the challenges facing maize conservation in their community before the conversation was then opened up to the group more broadly.

Following the focus group discussions, a common meeting was held for all of the participants to share the perspectives that emerged across the different age and gender groups. In this meeting, the participant groups shared their different views on the challenges and their causes. Bringing the participants together to discuss these differences as a group helped the work to reconcile the differences and bridge the different understandings of the value of and threats to native maize farming. In this meeting participants first worked in small groups to prioritize the identified challenges from the focus group discussions before a plenary session with all participants decided upon the priority challenges for the community as a whole and the potentially feasible solutions to be pursued.

Finally, a community-wide event was held in which, participants’ motivation to get involved in the project, their artworks, discussions, conclusions, and proposed solutions were shared with all community members, including those that had not participated in other parts of the project. The purpose of this event was to share the results of the project with a broader audience and to gather community support for the implementation of the solutions, hoping as well to increase the awareness of the role native maize plays in their identity and life and the importance of its conservation. Following this meeting, the shared strategies to address the challenges that were agreed on were implemented and/or begun.

In previous years, the community of Santiago Apostol had hosted a festival coordinated by the Oaxacan organisation of the Network in Defense of Maize to celebrate the value of native maize. However, the network decided to give other communities in Oaxaca the opportunity to host the festival and therefore it was no longer going to be being held in Santiago Apostol. Apostol participants in the project thought that continuing the festival and making it a tradition in the community would be a relevant strategy for addressing the challenges they identified related to native maize conservation. Therefore, participants in the project organised when the next festival was and specifically focused on including more members of the community in the planning process. In contrast, in Tutla, workshops in agroecological techniques were seen as an important strategy to confront the challenges they identified for native maize conservation. Internal conflicts (unrelated to the project) in the community of Tutla prohibited the workshops being implemented immediately. Although the project’s researchers facilitated one workshop after the conflicts were resolved, the momentum had been lost and interest for running further workshops decreased. Another strategy identified in both communities that aimed at the transfer of traditional farming knowledge was the establishment of experimental plots in schools. However, this was made difficult by an incompatibility between the schedules of the school year and native maize farming. The steps and activities performed in our case study are schematically described in

Figure 3.

After the conclusion of the CreativeVoice process, we conducted a voluntary and anonymous evaluative feedback process using a questionnaire with open-ended questions. This was to better understand how participants had experienced the method and to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of the approach, as perceived by them. The short questionnaire contained six questions that gathered information about the role that creating artwork played in getting them involved in the project and to what extent the use of various art forms was appreciated and useful for the participants (e.g., in terms of helping to stimulate reflection and discussion and as a mean to increase visibility, involvement and support at a community level). Quotations from participant answers to this questionnaire were translated by one of the authors to include them in this paper. On the basis of this questionnaire and our observations, we present the results and discuss the benefits and challenges associated with the CreativeVoice approach of integrating art and science for biodiversity conservation.

3. Results

Despite offering a broader range of creative art forms than Photovoice, we expected that photography would still be most appealing to many of the participants, especially the younger generations, who can often be attracted to technological tools. However, photography proved not to be the most popular choice among the art categories, and embroidery actually emerged as the dominant form chosen across both of our communities. This is particularly interesting since it was not originally presented in our category examples and highlights the value of remaining open in the art forms offered. For the women, embroidery dominated across all age groups and clearly demonstrates the significance of offering genres of the creative arts that connect with the community’s own culture. In Oaxaca, embroidery is a very traditional, common, and popular form of artistic expression. While embroidery was a form preferred by women rather than men, there was no dominant preference for it among any particular age group or community. Indeed, across the communities and age groups, a broad spectrum of different art forms was ultimately chosen, including embroidery, stories, drawings, photos, mural newspapers, and paintings (including watercolors, oil paintings, and a huge wall mural in the main street of one of the communities). Not only were a diverse set of creative arts employed by participants to tell their stories and give their perspectives, diverse challenges to maize biodiversity conservation were also highlighted through the CreativeVoice process. These included climate change, new social standards creating needs difficult to fulfill through maize farming, changes in agricultural systems from traditional to an agrochemical dependent system, agroindustry influence, and transgenic corn. The artwork captured and portrayed the history of maize in the communities and how this history plays an important role in their daily lives and cultural identity, such as their family connections and culinary uses. Examples of some of the artworks created during the CreativeVoice process and short descriptions of their representations are included in

Figure 4.

In the process of creating their artwork, participants increased their awareness of how maize biodiversity interacts with their history and daily life. Through the artwork and their presentation in the focus groups, participants reflected on the richness of maize and all the important links it had within their history and culture and all that could be lost if native maize diversity disappears. They reflected upon family and community links, diversity of culinary uses, and indigenous farmers’ food security and independence. In other cases, artwork was used to affirm the value of maize as life itself for these communities and the way that it will always survive because there will always be some farmers willing to conserve it and the traditional way of life (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). Indeed, through the questionnaire, participants expressed that before creating the artwork, they took the existence of this biodiversity and the social and cultural traits links to it largely for granted, without really reflecting on what they could lose if native maize disappears.

“It was like I was asleep. Maize gives us everything and now I see how important our native maize is and I’m more aware of its value over hybrid maize.”

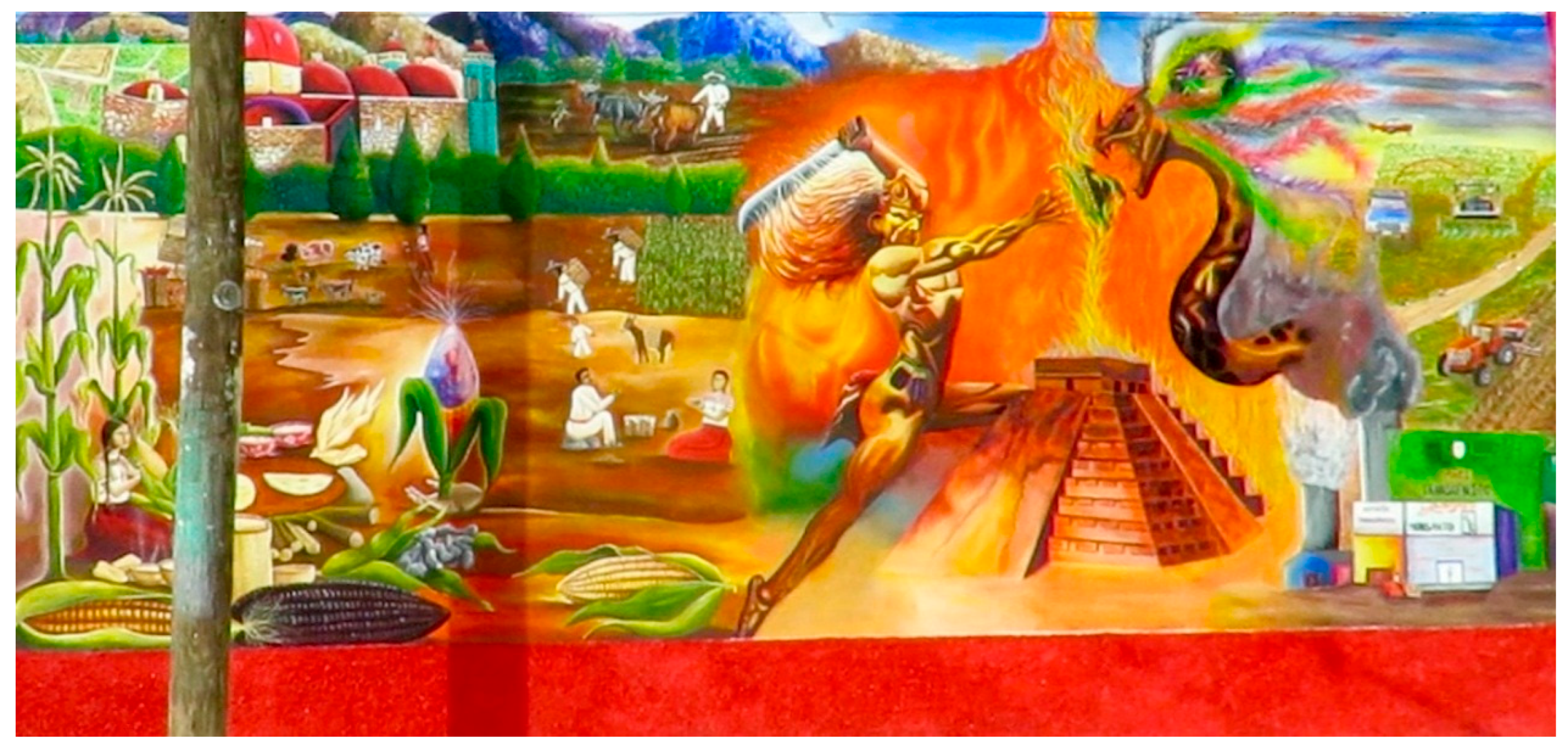

Particularly, in Apostol, the creation of a mural by seven young men facilitated reflections within the community on the value of native maize in their lives, history, and identity and how the agrochemical industry and new varieties are threatening it. Also, by creating this mural together, the young men were in contact with elders in the community, and this encouraged them to reflect on some of the important social links promoted by native maize farming that are now poorly practiced in their community, such as volunteer collective work. As one of the mural artists said,

“It was nice to reflect on maize and talk with elders about our history to paint the mural, but it was even nicer to remember the benefits of working collectively, as a team. We had fun and the work was less difficult. I guess that was the same feeling our grandparents had when they farmed collectively.”

This learning is important because if these cultural connections are forgotten, maize can appear as just another a food crop and/or a simple market product that can easily be replaced or substituted by other crops or products. Furthermore, without these deep connections between maize and these indigenous cultures being recognised, the value awarded to farming can decrease and the sense of pride in being a farmer be lost. All of these changes put conservation of native maize biodiversity at risk and were identified by participants as threats.

We aimed to increase the potential of the Photovoice method by opening up the choice of art forms to a wider range of possibilities. Rather than just recording current conditions with photographs, the broader range of artforms provided the participants with the opportunity to imaginatively travel through time and reflect over the conditions that could put native maize conservation at risk and how to value their own history and cultural identity moving forward. Artwork such as murals and embroideries were used to represent the long-term history of maize farming and changes over time, which would not have been possible through photography, which is typically limited to capturing the present or at least restricted to the historical photos available to participants.

We can confirm through the answers given in the evaluative questionnaire that participants positively welcomed the amendment to expand the Photovoice method with the freedom to choose the art form of preference. They stated that having the possibility of using traditional forms of artistic expression, such as embroidery, made them feel more comfortable, particularly as it seemed a more authentic or natural way to express themselves.

“It wouldn’t be the same thing with paintings or photos, which is not the traditional way. I like better embroidery as it is simpler for me and it is more of my tradition.”

One of the main benefits we experienced in using an art-based method in our participatory research was the way that it helped to disrupt the knowledge hierarchies between researchers and participants, which are often present in traditional research methods. Artworks serve as focal points for facilitating an easy sharing of perspectives and allowed conversations to take place within a relaxed atmosphere. There is no correct answer for creating or discussing artworks and their meaning. Art allows for the communication of perspectives beyond language and no particular expertise is required to comment on it or develop one’s own understanding and interpretation in relationship to it [

9,

11]. This was evident in our focus group discussions where participants could comment on the various artworks without feeling the need to have any special knowledge or expertise. Even better, recognising themselves as experts on the topic also empowered them to take action.

Even though not all participants made art, we found that having a least one artwork was essential to catalyse the conversations and discussions. In the focus groups, the artworks served as the means for participants to collectively remember, tell and reconstruct their history, helping them to become aware of the challenges facing native maize biodiversity conservation and the importance of addressing them together. Participants were able to build upon other participants’ memories and in their discussions about the challenges and their causes. This form of discussion connected participants with different social or economic statuses and different stories and lifestyles in the community, placing them on the same level as they all shared community memories. The artwork helped make the participatory process more equitable as they opened a space in which participants could recognize, remember, and discuss a common cultural identity. We also observed, the individual and collective level reflections created through the generation and discussion of artwork gave participants a greater sense of ownership over the project by allowing them to frame the problem and the solutions based on their own knowledge, experience, resources, and forms of expression.

The inclusion of a common meeting with participants of all the focus groups proved to be particularly important, especially for reconciling the different perspectives that emerged in the focus groups on the challenges facing native maize biodiversity conservation, their causes and the responsibility of each group in terms of their contribution to these challenges. For example, a key discussion topic that was brought to the common meeting was the lack of interest from youth in native maize farming. All participants, including the young, acknowledged the lack of interest from youth in native maize farming as a significant problem for keeping maize biodiversity alive. However, at this common meeting, it became clear that the elders were blaming the youth for being lazy and disrespectful by not valuing native maize as they should, while young participants felt that their parents and grandparents were pushing them away from the land in the name of progress (i.e., getting an education, finding better jobs and careers). During the common meeting we were able to collectively reflect on these disagreements and participants were then better able to see and accept their contribution to the problem. Mutual “forgiveness” occurred and a desire to work together towards native maize conservation was built, which would not have been possible if discussions had only taken place in focus groups.

While CreativeVoice allowed art forms such as written stories, the majority of artworks created in our project were visual arts. This created a particularly useful tool for participants to enhance the visibility of

their project and attract other community members’ interest in it. Participants joyfully noted how community members who were not active partners in the project could now see their history and cultural identity reflected in the artworks.

“I chose to participate because I could show our history. We cannot make the past come back, but we can always remember our history and I wanted to tell my history and to be remembered, I would love that people could work on the land as in the old days. Now it is not the same, but it was a beautiful way of doing things.”

“People who didn’t know about the project became interested in our work when they saw our artworks.”

“In this way (through the stories represented in the artworks) people in the community realized the importance of using native maize and were encouraged not to buy other kinds of maize sold in the stores.”

The artworks also increased awareness and promoted reflections among non-participant community members concerning the value of native maize and the changes that could put it at risk over time. They also became aware that members of their community were willing to implement strategies to try and overcome some of the challenges and that these active members needed support from the community to achieve the goal of native maize conservation. This was more evident in the case of Apostol, where the wall mural served as a constant reminder of the importance of native maize for Apostol members’ history and cultural identity and how non-native seeds and agriculture systems are threatening its ongoing conservation (

Figure 7).

4. Lessons Learned from Using CreativeVoice

CreativeVoice shares the benefits claimed by other Photovoice and art-based research projects, such as being a powerful tool to promote reflection and raise awareness of the issue at stake, empowering participants by recognising their knowledge and expertise, and supporting more equitable relations between researchers and participants [

3,

6,

7,

15,

30]. CreativeVoice also adds advantages for participatory sustainability research by overcoming some of the limitations found in Photovoice method and lends itself to easy adaptation to a range of age, gender, or cultural contexts.

In our study, the creation of artwork offered significant benefits for fostering individual level reflections among relevant actors for the sustainability challenge we were focused on, namely the conservation of native maize biodiversity. The artworks were also potent catalysers for discussions during focus group sessions, which enhanced collective level reflections on the topic. Since no specific expertise or involvement of professional artists is needed to discuss, interpret and share stories when various forms of artistic expression are available (in contrast to PhotoVoice, where instruction from professional photographers is often involved), our method decreased the potential for hierarchical relationships between the research team and participants to emerge. Decreasing the inclusion of external collaborators, such as the professional photographers used in Photovoice, also increased the participants’ self-reliance and recognition of their own capacities, and reinforced their ownership over the project. Artwork is a powerful means to explore in depth perceptions, emotions, and histories related to native maize among farmers and community members and attractive tools to engage the attention of non-participants, bringing the opportunity to think about native maize conservation to a broader audience. Together, this had the effect of helping to empower participants to recognize the validity of their own knowledge and expertise and to take the appreciation of other community members regarding their concern for native maize conservation in their community as further inspiration and motivation for action.

The task given to participants in our CreativeVoice case study—to reflect on the history of changes affecting native maize biodiversity conservation—had an important influence on their reflections and findings. We encouraged the participants to tell their own stories through different type of art forms. Our observations regarding the value of art for doing this supports the findings of Fernández-Llamazares and Cabeza [

24] that storytelling can be a powerful vector for identifying key threats to native maize biocultural conservation, as well as for promoting knowledge transfer and reducing the distance between generations. In addition, we observed that discussing community memories related to native maize during the focus group discussions helped create an atmosphere of equity among participants from different social and educational levels in the community, since they all shared the same historical background and were facing the same problems.

We witnessed that through the steps of CreativeVoice, participants could experience the phases needed to reach Freire’s critical consciousness, as also demonstrated in other studies using Photovoice [

16]. These phases include first a “magical phase” in which people accept their (undesirable) situation as fate without contesting or reflecting on it. In this phase, they feel incapable of transforming the situation and they expect it will improve without their active participation. The second phase is a “naïve phase” in which people achieve an awareness of the problem and its causes but do not reflect on their own responsibilities and contributions to the problem, rather they tend to blame their peers. Finally, there is a “critical phase” in which people are capable of assuming some responsibility for the problem. In this phase, people can identify their capacities to transform the situation towards positive change through collective actions [

44]. We observed that through the creation of artworks and the focus group discussions, participants could enter the naïve phase by having individual reflections on the challenges of native maize conservation in their communities and the potential causes of these challenges. During the focus groups, we observed that the participants had difficulties articulating potential solutions to the identified challenges and were blaming others for the undesirable parts of their reality, particularly in Apostol, where elders blamed the young and vice-versa. However, in the joint meeting, where the discussions from the focus groups were shared and collectively reflected upon, participants could recognise their own responsibilities and actively worked to reconcile their differences. This saw them thinking about their own capacities and desires to positively change the current situation and allowed them to enter into the critical phase by collectively creating solutions to defend the diversity of native maize in their communities and finding the motivation to act. We cannot claim that our project achieved a transformative change at a community level. However, we could identify that through the different steps of CreativeVoice, an individual transformation in the participants occurred and therefore ignited in them the will to take action for positive change in their community. Particularly in the case of Apostol, participants did follow their desire to continue the festival and turn it into a tradition in the community, by continuing to organize it again in later years with the support of the local authorities.

We also observed that the modifications we made to the traditional Photovoice method in our CreativeVoice approach created significant additional benefits. As in Castleden and Garvin [

27], we found it highly beneficial to stay flexible and not restrict the enrolment of participants to only one recruiting session. Allowing an extended time for recruitment and using personal visits to potential participants to encourage their participation proved useful to motivate members to join the project and helped us clarify any potential doubts. Furthermore, the visits and individual informal interviews allowed us to create a deeper understanding of individual perspectives, including the perspectives of those gender and age categories who were not able to participate more actively due to time restrictions. Also, we saw that these visits helped to increase the trust from participants and community members in the research team and to create a more harmonious and horizontal relationship based on the informal exchange of thoughts, perspectives and personal memories. Particularly in Apostol, participants expressed that these visits made them overcome the fear (created by previous experiences with researchers) of participating in something that would potentially only extract their knowledge and to reassure them that they were getting involved in a truly collaborative project.

CreativeVoice has also gained much from offering a broad spectrum of art forms to participants. As was our initial hope, CreativeVoice overcame the Photovoice challenge of potentially restricting participation from older members of the community, a limitation also of concern to Castleden and Garvin [

27]. We felt that elders could find it difficult to manage a camera and would not feel comfortable expressing their perspectives through photography, which could decrease their feeling of ownership over the project. Since CreativeVoice was open to any kind of art, the technological and mobility requirements of the traditional Photovoice method were no longer present. In fact, the lack of requirements for any particular set of special skills or resources means that CreativeVoice has the advantage of being adaptable to any age, gender, or cultural context. The modification of Photovoice made by Glenis and Boulton [

29] to create Maori-Voice, was further extended in our study. Since we also felt it was important to allow for cultural adaptation, we left the choice of art form open as a way to allow the method to discover and enable local preferences to emerge, such as embroidery in our case. Moreover, not imposing particular artforms based on assumptions of their cultural relevance also proved to be important. For example, in Tutla our expectation that music or poems would be used was high due to their historical significance of music in this community as a traditional form of artistic expression. However, participants did not opt for any song, melody, or poem to express their perspectives regarding native maize conservation. In contrast, their choices were more connected to embroidery, drawings, and paintings. This means that we consider it important to remain open for the use of all types of art forms, even when you expect certain forms to be of particular relevance within a certain culture or community.

While our experience supported the notion that integrating art into research offered significant benefits, we certainly faced some difficult questions and challenges while applying the CreativeVoice approach and would like to present these so as to prepare others that may be interested in adopting and trying the approach. CreativeVoice certainly shares some challenges faced by other art-based methods, such as the ethical issues considered in [

30]. To address some of these, we made the decision that the participants would always retain ownership of their artwork and made sure they were aware of this. However, we still needed to find a way to balance potential expectations for confidentiality and acknowledgement when presenting the project’s work. In our case, we created a consent form in which it was stated that information from the group discussions and the feedback questionnaire would always remain confidential, however, they had the option of giving us permission to use images of their artworks with acknowledgement of them as the creators.

We also found that while some participants were very motivated to create artworks, others were somewhat scared or overwhelmed by the idea, either due to the time it was perceived as requiring or a sense of their own lack of artistic abilities. For some people, the creation of artworks was seen to require particular creative skills that they felt themselves lacking in. In the beginning, we encouraged all participants in the project to create an artwork. However, we saw that this was excluding those members of the community that were interested in the topic but were not enthusiastic about creating art. To address this challenge associated with our method, we therefore decided to make the creation of an artwork optional and not a requirement for participating in the focus group or community level discussions. We would, however, suggest that for the method to be effective, it is important to secure at least one artwork for any group discussion and indeed to have more participants producing artworks than not to ensure that a diverse range of works and perspectives can be used to spark and stimulate discussions.

As for every participatory research project, we had to be sensitive to the inner dynamics of the communities and try to avoid provoking any trouble or exacerbating any inequalities. We knew that previous research projects working in the communities had offered money in exchange for participation and that this had provoked divisions and misunderstandings. Wanting to avoid this, we constantly clarified that we would not give or receive money. However, we did offer art materials to those involved in the project since we did not want participation in the project to create a financial burden. This sometimes required careful reflection and navigation. For example, the provision of different amounts and qualities of materials to different participants can create jealousy or a feeling of discrimination among them. Giving everyone the option to create any form (and size) of artwork they like inevitably creates challenges for how to distribute materials in a fair manner. Our approach was to be open with the participants that the selection of materials was up to each of them and was therefore not about us favoring certain participants over others. It is also relevant to reflect on how to deal with people requesting more materials than they may need to create their artwork. To deal with this, we set a limit on the provisions, depending on the type and scale of the artwork being created.

However, perhaps the greatest difficulty we faced was in communicating the task and having our participants accept that they were being given the freedom to create whatever they wanted within the context of our research project. Furthermore, when we asked participants to create an artwork, we were initially apparently not providing any new knowledge and this seemed like we had nothing to offer them. In the traditional Photovoice method, the training workshop could give participants the feeling that they were learning new skills in exchange of their participation. However, in the beginning of CreativeVoice, it was uncertain for participants what they had to gain from being involved in the project. Since the real value of the artworks did not actually emerge until the focus group and community level discussions and exhibitions, the participants therefore had to overcome a feeling that they may be wasting their time in the phase of creating the artworks. As researchers, we also had to be patient and persistent since we had to explain the task often and continue to offer encouragement until the participants could really feel engaged in the project and start making their artworks. Consequently, it takes time and patience from both the researchers and participants to generate a sense of clarity and ownership over the CreativeVoice process.

We also experienced some level of participant inconsistency and quitting, which lead to a reduction in the number of participants participating in focus group discussions from what was initially registered (although some of these participants chose to rejoin at later stages of the project). We also experienced interest from other community members that wanted to be included in the later steps of CreativeVoice, such as to participate in the joint meeting. We considered it important that our project be inclusive and therefore chose to remain open to newly interested people at various stages of the project, as we found this important for assuring continuity of the conservation efforts beyond the life of the project and the support of the community to keep pursuing the shared solutions and action steps agreed upon. We asked the initially registered participants if they agree to include new people and the process they would like to see followed for doing this. This is important to keep and increase the participants’ feeling of ownership over the project and how it proceeds. While we experienced a positive transformative potential in the application of the CreativeVoice method, we do recommend further follow-up studies for documenting the value of the method in other contexts as well as the level of ongoing actions taken towards biocultural native maize conservation in the communities we worked with