Abstract

As hacking techniques become more sophisticated, vulnerabilities have been gradually increasing. Between 2010 and 2015, around 80,000 vulnerabilities were newly registered in the CVE (Common Vulnerability Enumeration), and the number of vulnerabilities has continued to rise. While the number of vulnerabilities is increasing rapidly, the response to them relies on manual analysis, resulting in a slow response speed. It is necessary to develop techniques that can detect and patch vulnerabilities automatically. This paper introduces a trend of techniques and tools related to automated vulnerability detection and remediation. We propose an automated vulnerability detection method based on binary complexity analysis to prevent a zero-day attack. We also introduce an automatic patch generation method through PLT/GOT table modification to respond to zero-day vulnerabilities.

1. Introduction

The number of vulnerabilities is increasing rapidly due to the development of new hacking techniques. Between 2010 and 2015, around 80,000 vulnerabilities were newly registered in the major database known as the CVE (Common Vulnerability Enumeration) [1]. In recent years, the scope of security threats has also been expanded; i.e., IoT [2], Cloud [3], etc. The number of zero-day vulnerabilities has soared to the point that specialists can no longer be relied upon to respond to vulnerabilities. In order to respond quickly to a zero-day attack, automated vulnerability detection and automatic patching processes are necessary. In this paper, we propose a technology that performs fuzzing and symbolic execution based on binary complexity to automatically detect vulnerabilities. In addition, we propose an automatic patching technique to modify the GOT/PLT table to patch binary for a quick response to the attack of an automated vulnerability detection. In Section 2, we analyze trends and techniques for automated vulnerability detection and automated vulnerability remediation. In Section 3, we introduce our method that automatically detects vulnerability using a hybrid fuzzing based on binary complexity analysis and automatic patch vulnerability by loading a safe library through the GOT/PLT table modification. In Section 4, our experimental results are presented. Finally, in Section 5, we discuss our conclusion and future work.

2. Related Works

2.1. Automated Vulnerability Detection

2.1.1. Fuzzing

Fuzzing is a testing method that causes the target software to crash by generating random inputs. Fuzzing was first introduced by the University of Wisconsin’s Professor Miller Project in 1988 [4]. The project was promoted to test the reliability of Unix utilities by generating random inputs. The professor in this project confirmed that arbitrary input values were delivered to the computer under the influence of the storm while trying to login remotely to his computer. The program was terminated due to the unintended input value and this experience evolved into the concept of fuzzing, which injects random input values into software and causes errors.

Fuzzing is divided into dumb fuzzing and smart fuzzing, and is dependent on input modeling and divided into Mutation Fuzzing and Generation Fuzzing according to the test case generation method. Dumb fuzzing is the simplest form of fuzzing technology because it generates defects by randomly changing the input values to the target software [5]. The test case creation speed is fast because it is simple to change the input value; however, it is difficult to find a valid crash because the code coverage is narrow. Smart Fuzzing is a technology that generates input values suitable for the format through target software analysis and the generation of errors [6,7,8,9]. Smart fuzzing has the advantage of knowing where errors can occur through a software analysis. A tester can create a test case for that point to extend code coverage and generate a valid crash. However, there is a disadvantage in that it requires expert knowledge to analyze the target software, and it takes a long time to generate a template suitable for software input. Mutation fuzzing is a test technique to modify the data samples to enter the target software. Generation fuzzing is a technology that models the format of the input values to be applied to the target software and creates a new test case for that format. Recently, an evolutionary fuzzing technique has been introduced that generates new input values by providing feedback on the target software’s response [10,11].

2.1.2. Symbolic Execution

Symbolic execution is a technique that explores feasible paths by setting an input value to a symbol rather than a real value. The symbolic execution was first published in King’s paper in 1975 [12]. This test technique was developed to verify that a particular area of software may be violated by the input values. The symbolic execution is largely divided into the offline symbolic execution and the online symbolic execution. The offline symbol execution solves by choosing only one path to create a new input value by resolving the path predicate [13]. The program must be executed from the beginning to explore other paths, so there are disadvantages because it causes overhead due to re-execution. The online symbolic execution is the way in which states are replicated and path predicates are generated at every point where the symbol executor encounters the branch statement [14,15]. There is no overhead associated with reissuing using the online method, but the downside is that it requires the storage of all status information and the simultaneous processing of multiple states, leading to significant resource consumption. In order to solve this problem, the hybrid form symbol is suggested.

The hybrid symbolic execution saves state information through online symbolic execution whenever a branch statement is executed and proceeds until memory is exhausted [16]. When there is no more space to save, a switch to the offline symbolic execution occurs and a path search is performed. We have solved the memory overflow problem of the online symbolic execution by applying the method of saving the state information and using it later through the hybrid symbolic execution. In addition, it solves the overhead of the offline symbolic execution because it does not need to be executed again from the beginning. In recent years, the concolic execution, which is a method of testing by substituting an actual value (Concrete Value) and testing a mixture of symbolic executions, has been proposed. This technique is a technique of actually assigning a concrete input value and generating a new input value by solving the path expression when the actual input value meets the branching statement. The reason for executing the actual value is that if the symbolic executor encounters a difficult problem and it takes a long time or does not solve the problem, the test can no longer be performed. However, if the actual value is substituted, a deeper path search becomes possible.

2.1.3. Hybrid Fuzzing

The hybrid fuzzing method is a technique where the automatic exploitation of vulnerabilities combines the advantages of fuzzing to generate random input values with the concolic execution to track the program execution path. The hybrid fuzzing solves the fuzzer incompleteness and the path explosion problem of the concolic execution. Driller is a typical tool for hybrid fuzzing [17]. The driller uses the fuzzer to search for the initial segment of the program. If the process is stopped by the conditional statement, the concolic engine is used to guide the next section and the fuzzer takes over again and searches for vulnerabilities in the deep path more quickly. Driller is a hybrid fuzzing tool using AFL (American Fuzzy Lop) [9] and Angr [18]. AFL is a fuzzer that generates and transforms input values through a genetic algorithm and Angr is an engine that performs symbol execution by converting binary codes into Valgrind’s VEX IR, which is also known by Mayhem and S2E [19] as the most optimized symbol execution engine. The driller performs fuzzing through the AFL and calls the concolic execution engine Angr for the purpose of finding a new state transition path, if the fuzzer is no longer able to find additional state transitions. In this case, the main reason that the fuzzer cannot find the additional state transition path is that it cannot generate specific input values to satisfy complex conditional statements in the software. The concolic execution engine that receives the control right at that point generates the input value, satisfying the complex condition by using the constraint solver. The generated value is passed to the fuzzer’s queue and the control is also passed to the fuzzer to perform the fuzzing. The driller can perform this process repeatedly to search for a fast and deep path. An important factor in determining efficiency in this analytical flow is the avoidance of the path explosion, which is a limiting point inherent in the concolic execution. This is because the limited execution path is analyzed by the input value generated through the fuzzing. The tools and features related to automated vulnerability detection techniques are shown in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Automated Vulnerability Detection Tool Comparison.

2.2. Automated Vulnerability Remediation

2.2.1. Binary Hardening

Binary Hardening can be divided into OS-level memory hardening technologies and Compiler-level binary reinforcement technologies. First, OS-level memory-enhancing technologies include ASLR (Address Space Layout Randomization), DEP (Data Execution Prevention/Not Executable), and ASCII—Armor. The ASLR is a technique that provides an Image Base value randomly when a program is mapped to a virtual memory. It is a security technique that prevents attacks by making it difficult for attackers to figure out the memory structure of the target programs. DEP/NX is a technology to prevent code from being executed in data areas such as stacks and heaps. It limits the execution authority over the stack or heap area, thereby preventing attacks. ASCII—Armor is a technology that protects a shared library space from the buffer overflow attacks by inserting NULL(\x00) bytes in the top of its address. The inserted NULL bytes make it impossible to reach the address.

The technologies that are applicable to the compilers are PIE (Position Independent Executable), SSP (Stack Smashing Protector), and RELRO (Relocation Read-Only. First, PIE is a technology that is similar to the ASLR provided by the operating system to apply the logical addresses during the compilation so that the addresses mapped to the virtual memory are random each execution time. The difference with ASLR is that the ASLR applies the random address to the stack, heap, and shared library space of the memory area and the PIE applies the logical addresses in binary to randomization. A SSP is a technique to prevent an attack that can overwrite SFP (Saved Frame Pointer) by inserting a specific value (Canary) for monitoring into the stack, especially between the buffer and SFP. In case of a buffer overflow attack, to overwrite the SFP, an attacker also overwrites the canary so that the monitoring modulated canary detects the buffer overflow attack. Finally, the RELRO is a technology to protect memory from being changed by making the ELF binary or data area of the process read-only. There are two types of methods, partial RELRO and full RELRO, depending on the state of the GOT domain. Although partial RELRO with a writable GOT domain can consume less resources and execute faster than full RELRO, it is vulnerable to attacks such as a GOT overwrite. On the other hand, full RELRO with a read-only GOT domain consumes more resources and is slower than the partial RELRO, but it could prevent the attack using the GOT domain. Features related to binary hardening techniques are shown in the Table 2.

Table 2.

Binary Hardening technique comparison.

2.2.2. Automatic Patch Generation

A major technology for automatic patch generation is generating patches using genetic algorithms. Genprog, announced in 2009, is the technology that has had the biggest impact on studies on automated patching [20]. Genprog a technique to automatically patch C language-based programs. After converting the source code structure of the target software to AST (Abstract Syntax Tree), it patches the anomaly node with three modifications; delete, add, and replace. To modify nodes, it uses templates for each error. According to the study, 55 of the 105 common bugs were modified, and vulnerabilities such as Heap Buffer Overflow, Non-Overflow Dos, Integer Overflow, and Format String vulnerability were patched.

Another technology for automatic patch generation is automated patch generation using error report information. R2Fix is the typical tool for generating a patch automatically using error report information, it is based on the fact that there are many errors in the developed software that have not been modified due to a lack of resources to correct the already known errors [21]. R2Fix automatically performs patches by combining error correction patterns, machine learning, and patch generation techniques. R2Fix consists of three modules: Classifiers, Extractor, and Patch Generator. Classifiers apply machine learning to collect error information from error reports and automatically categorize, Extractors extract the general parameters (file name, version, etc.) and detailed information parameters (buffer name, size, bound check condition, etc.) for each type of error, and lastly, the Patch Generator generates and applies patch codes using modification patterns. According to the study, R2Fix performed a vulnerability patch for buffer overflow, null pointer reference, and memory leakage in Linux kernels, Mozilla, and Apache. It also created 57 patches for common errors, five of them were patches for new errors not expected by the developer.

Among the automatic patch generation technologies, there is a technique using patch information written by experts. PAR is a representative tool for generating patches by automatically using patch information written by experts [22]. It manually analyzes more than 60,000 patches to find several common patterns, and automatically generates patches based on those patterns. PAR creates patches through a total of three steps: Fault Localization, Template-based Patch Candidate Generation, and Patch Evaluation. The Fault Localization phase uses a statistical fault positioning algorithm that assign weights to each running syntax based on a Positive/Negative test case. In this step, the key assumption is that the syntax on which the Negative test case is executed is likely to be faulty. First, it runs both test cases and records the route. The route is then divided into four groups, (1) execution syntax visited by both groups; (2) execution syntax for visiting Positive only; (3) execution syntax for visiting Negative only and (4) execution syntax not visited by both groups, and assigned weights. The weights are 1.0 for (3), 0.1 for (1), and 0 for others. Depending on the weights assigned, this creates a candidate patch on that position. During the Template-based Patch Candidate Generation phase, a total of 10 modification templates are applied, including Parameter Replacer, Method Replacer, and Expression Replacer, for each fault location and each candidate patch. The generation of candidate patches is carried out in three stages: (1) AST Analysis; (2) Context Check; and; (3) Program Edition. Step (1), AST scan of the target program occurs and it analyzes the location of the error and its proximity. Step (2) examine whether it is possible to modify the location with the modification template and, if applicable, create a candidate patch by rewriting the AST for the target program based on the script that is predefined in the modify template in Step (3). Finally, the Patch Evaluation phase evaluates the suitability of the candidate patches created using the various test cases collected from the issue trackers (Bugziila, JIRA, etc.) of the target program. For each candidate patch, the candidate patch carrying out all test cases are selected and applied as final patches.

3. Automated Vulnerability Detection and Remediation Method

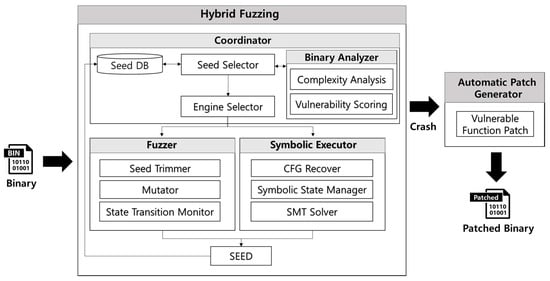

Fuzzing works much faster than symbolic execution and is capable of exploring a deeper range of code depths. However, it is difficult for a fuzzer to explore widespread code. Symbolic execution can discover possible paths of the program, but exploring is limited due to path explosion with an explosive number of paths. Many types of hybrid fuzzers are available to complement these mutual strengths and weaknesses. However, most hybrid fuzzers choose a vulnerability detection engine without analyzing the target program. A program has complex parts such as loops and recursions that are hard to explore, but some parts of the program are simply reachable. Accordingly, it is possible to identify which parts are advantageous for fuzzing or symbolic execution. In this paper, we introduce a binary analysis method to identify the advantageous areas for fuzzing and symbolic execution, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Automated Vulnerability Detection and Remediation Architecture.

Hybrid fuzzing based on binary analysis selects fuzzing and symbolic execution through binary complexity metrics. Using the selected vulnerability search engine, it creates a new seed that causes a state transition. The newly created seed is used to analyze the binary complexity again and repeats the same process. Hybrid fuzzing based on a binary analysis will then proceed to the next five steps:

- Seed Selection: Seed selection is a step to select the input value to be used for vulnerability detection. In a first iteration, a seed scheduler selects a seed defined by the user to detect vulnerability. From a second iteration, a new seed created by the seed generation engine is selected for the next step.

- Binary Analysis: A binary analysis module executes the target binary in an instrumentation environment. As a binary is executed, disassembly code and function call information are extracted through binary instrumentation. Binary complexity and vulnerability scores are analyzed using the extracted information. The results of the complexity analysis determine whether to run a fuzzer or symbolic executor to detect vulnerabilities. The results of the vulnerability score will be used to determine whether a detected crash is exploitable in future research.

- Engine Selection: The engine selection module chooses one of the fuzzing and symbolic execution engines according to the result of the complexity analysis. The symbolic execution engine is executed if the complexity analysis result is smaller than a specific threshold; otherwise, the fuzzing engine is selected.

- Seed Generation: The fuzzer or symbolic executor is executed to generate seeds to be used in the next iteration. The seed generation process is performed until a state transition occurs. When a state transition occurs, the seed value that caused the state transition is stored in the seed DB.

- Repeat.

For automated vulnerability remediation, the vulnerable function-based patch technique is utilized to create a weak function list and modify the PLT/GOT with respect to the corresponding functions, to induce a call to a safe function. This is an application of the mechanism of lazy binding that the binary performs as a dynamic linking method to use a shared library. In addition, as shown in Table 3, the vulnerable function list is composed of 50 functions that can cause each of the four types of vulnerability, such as buffer overflow, format string, race condition, and multiple command execution.

Table 3.

List of Vulnerable Functions by Vulnerability Type.

3.1. Binary Analysis

3.1.1. Instrumentation

To extract binary information, we leveraged a QEMU instrumentation tool [23]. QEMU is a virtualization tool that is often used for binary dynamic analysis. QEMU produces a TCG (tiny code generator) that converts binary code to IL (intermediate language). After converting, QEMU inserts a shadow value at the IL to extract the information we want to analyze. We utilize this instrumentation function to obtain disassembly code information and function call information.

3.1.2. Complexity Analysis

We utilized the Halstead complexity metrics to analyze binary complexity. The metrics were published in 1977 by Maurice Howard Halstead [24]. The metrics are intended to determine the relationship between measurable properties and Software Complexity. The metrics were originally developed to measure the complexity of the source code, but we applied it to measure the complexity of the assembly code. We analyzed the binary complexity by measuring the number of operators and operands in the assembly code using the metrics in Table 4.

Table 4.

Halstead Complexity Metrics.

3.1.3. Vulnerability Scoring

When executing the binary, it traces all the function calls of the executed path. In the traced function calls, we check whether a function from the vulnerable functions shown in Table 5 is called. We assigned a vulnerability score separately for dangerous functions and banned functions as shown in Table 5. The number of a called function, which is defined as a dangerous function, is shown in Table 5. We accumulate scores whenever a dangerous function or a banned function is called. We refer to research on detecting vulnerabilities through software complexity and vulnerability scoring [25]. We are planning to extend this research to automatic exploit generation and automatic patch generation.

Table 5.

Functions for Vulnerability Scoring.

3.2. Engine Selection

The Engine Selection Module choose between the fuzzing and symbolic execution engine through a complexity analysis of the target binary. For the complexity analysis, the user defined the threshold value and put this value as an input of the engine selection. The number of operators, number of operands, total operators, and total operands extracted from dynamic binary instrumentation are used to measure program difficulty. If the program difficulty is lower than the threshold, the engine selection module chooses the symbolic executor. If not, the fuzzer is selected. The algorithm for the vulnerability detection engine selection is as follows.

| Algorithm: Selection of Vulnerability Detection Engine |

| Input: Threshold T Data: Difficulty D, , , , Result: Seed S function Engine Selection(T); begin D ← Complexity (, , , ); if D < T then S ← Symbolic Executor(); else S ← Fuzzer(); end return S; end |

3.3. Fuzzing

We used AFL (American Fuzzy Lop), which is an evolutionary fuzzer using a genetic algorithm. AFL performs fuzzing in three main steps. First, the AFL mutates the seed value with various bit mutation strategies (e.g., interest bit flip, subtract/add bit flip). Second, the AFL continues to monitor the execution status and records the state transition to expand code coverage. Third, the AFL trims parts that do not affect the state transition to minimize the range of mutation. By repeating the above three steps, the input value is developed in the direction of the state transition. We did not modify the core engine of the AFL Fuzzer and considered only its coordination with the symbolic executor. The Fuzzer operates when the binary analysis result is greater than the threshold.

3.4. Symbolic Execution

The Angr tool was used for Symbolic Execution. Angr utilizes Valgrind’s VEX IR to build a symbolic execution environment. SimuVEX, which is a VEX IR emulator, produces an environment to execute a symbolic state translated from binary through VEX IR. If the branch statement is encountered while executing binary, the path predicate for the branch is generated and the z3 solver tries to solve the constraint in the path predicate. Angr also provides various functions for analyzing the control flow graph. The main function is backward slicing, which helps to locate the source of a variable on a program slice. We will develop this backward slicing function to find the root cause of a vulnerability. It produces two methods to recover the control flow graph. We did not modify the symbolic execution engine. The symbolic executor operates when the binary analysis result is less than the threshold.

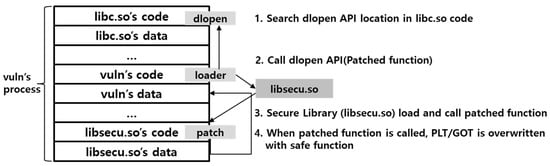

3.5. Automatic Binary Patch

The execution file of the Linux environment is the ELF (Executable and Linkable File) format. The structure of the ELF file is briefly shown in Figure 2, of which the text section contains the code necessary for execution. In this section, the code is the main () function and is the initialization for configuring the execution environment, consisting of argc/argv argument processing, stack setting, library loading for normal execution of the main () function, and the termination processing code.

Figure 2.

ELF file structure modification.

Replacing the constructor area of the binary with the secure library loader (secure_libs_loader) ensures that GOT can be changed before the main () function calls the weak function. The role of the loader is to ultimately load libsecu.so, which is a safe library in the same memory space as binary. The loader finds the address of the first dlopen () function as shown in Figure 3, and loads libsecu.so in the memory. After libsecu.so is loaded, the loader calls a function that performs a PLT/GOT patch within the library.

Figure 3.

Secure_libs_loader operation process.

All processes occur before the main () function is executed. Therefore, the patch process accesses the GOT via the PLT of the vulnerability function to which the actual address is not yet bound. Since it has never been called, the patch is executed by overwriting the GOT of the vulnerable function with the address for the binding (usually PLT + 6 location) with the address of the safe function.

This technique is aimed at minimizing binary modification and indirectly replacing vulnerable functions with safe functions. In other words, it is necessary to modify the constructor in order to load the library of the binary circle, but there is no need to worry about the side-effects, such as destroying the original program without touching other code parts. In addition, since the loaded library is in the form of a shared library, it can be maintained and repaired independently. IoT devices such as smart phones and smart TVs based on Linux are more likely to be applied as targets, therefore flexibility and scalability can be expected.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. CFG Recovery Analysis

CFG recovery analysis is often used for the static analysis of vulnerabilities. Among the CFG recovery techniques, backward slicing is useful for root cause analysis because it extracts the only path information in which the binary is executed. We have a plan to utilize this analysis method to analyze the root cause of vulnerability. For benchmarking, we compared CFG recovery speed with the following tools, shown in Table 6, targeting 131 species of CGC challenge binaries [26]. We compared these tools on a server with a 3.60 GHz Intel Core i7-4960X 2 CPU and 4 GB of RAM. The backward slicing tool was slowest because of resource consumption, and the fastest tool was BAP with 1.63 s.

Table 6.

CFG Recovery speed comparison.

4.2. Binary Patch Result

We used a Peach Fuzzer to trigger crashes of the open source software and compared the number of crashes before and after applying the patches in order to evaluate how many crashes we can eliminate through the automatic patch method. We chose eight open sources that were selected in descending order of the number of published vulnerability reports. We evaluated our method on a server with a 2.30 GHz Intel (R) Xeon E5-2650v3 CPU and 64 GB of RAM. The vulnerable functions shown in Table 7 were converted to safe functions by safe library loading. Let B be the number of crashes before the patch, and A be the number of crashes after the patch. The method of measuring the crash removal rate was evaluated as R as shown in the following equation.

R(%) = (B − A)/B × 100

Table 7.

Comparison before and after patch.

As a result, the average vulnerability removal rate was 59%, and the vulnerabilities of 25% binaries were completely removed by automatic patch.

5. Conclusions

The number of vulnerabilities is increasing rapidly due to the development of new hacking techniques. However, time-consuming software analysis depending on a vulnerability analyst make it difficult to respond to attacks immediately. We proposed a method of Hybrid Fuzzing based on a binary complexity analysis. We also introduced an automated patch technique that modifies the PLT/GOT table to translate vulnerable functions into safe functions. The proposed model removed an average of 59% of crashes in eight open-source binaries, and 100% in two binaries. Because a 100% removal rate of crashes means that they are not exploitable, the result is significant, which means that a hacker cannot attack any more. With these results, we can respond more quickly to hacker attacks without the help of experts.

As a subject of future study, we will study automatic exploit generation to verify the patched binary and root cause analysis of vulnerability to patch vulnerable parts directly. We will also research the automatic classification of vulnerabilities by modeling various data mining techniques [27,28] and machine learning techniques [29,30].

Author Contributions

J.J. designed the system and performed the experiments; T.K. contributed to study design; H.K. help revise paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Institute for Information & communications Technology Promotion (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2017-0-00184, Self-Learning Cyber Immune Technology Development).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- U.S. National Vulnerability Database. Available online: http://cve.mitre.org/cve/ (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- Kang, W.M.; Moon, S.Y.; Park, J.H. An enhanced security framework for home appliances in smart home. Hum.-Centric Comput. Inf. Sci. 2017, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, N.; Ji, S.Y.; Chaudhary, A.; Concolato, C.; Yu, B.; Jeong, D.H. A survey of cloud-based network intrusion detection analysis. Hum.-Centric Comput. Inf. Sci. 2016, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.P.; Fredriksen, L.; So, B. An empirical study of the reliability of UNIX utilities. Commun. ACM 1990, 33, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zzuf—Caca Labs. Available online: http://caca.zoy.org/wiki/zzuf (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- Peach Fuzzer. Available online: https://www.peach.tech/ (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- Sulley. Available online: https://github.com/OpenRCE/sulley (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- Aitel, D. An introduction to SPIKE, the fuzzer creation kit. In Proceedings of the BlackHat USA Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 29 July–1 August 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bekrar, S.; Bekrar, C.; Groz, R.; Mounier, L. A taint based approach for smart fuzzing. In Proceedings of the IEEE Fifth International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation, Montreal, QC, Canada, 17–21 April 2012; pp. 818–825. [Google Scholar]

- American Fuzzy Lop. Available online: http://lcamtuf.coredump.cx/afl/ (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- Honggfuzz. Available online: https://github.com/google/honggfuzz (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- King, J.C. Symbolic execution and program testing. Commun. ACM 1976, 19, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godefroid, P.; Levin, M.Y.; Molnar, D.A. Automated whitebox fuzz testing. NDSS 2008, 8, 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Cadar, C.; Dunbar, D.; Engler, D.R. KLEE: Unassisted and Automatic Generation of High-Coverage Tests for Complex Systems Programs. OSDI 2008, 8, 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Ciortea, L.; Zamfir, C.; Bucur, S.; Chipounov, V.; Candea, G. Cloud9: A software testing service. ACM SIGOPS Oper. Syst. Rev. 2010, 43, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.K.; Avgerinos, T.; Rebert, A.; Brumley, D. Unleashing mayhem on binary code. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–23 May 2012; pp. 380–394. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, N.; Grosen, J.; Salls, C.; Dutcher, A.; Wang, R.; Corbetta, J.; Shoshitaishvili, Y.; Kruegel, C.; Vigna, G. Driller: Augmenting Fuzzing through Selective Symbolic Execution. NDSS 2016, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Shoshitaishvili, Y.; Wang, R.; Salls, C.; Stephens, N.; Polino, M.; Dutcher, A.; Grosen, J.; Feng, S.; Hauser, C.; Kruegel, C. Sok: (State of) the art of war: Offensive techniques in binary analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, San Jose, CA, USA, 22–26 May 2016; pp. 138–157. [Google Scholar]

- Chipounov, V.; Kuznetsov, V.; Candea, G. S2E: A Platform for In-Vivo Multi-Path Analysis of Software Systems. In Proceedings of the Architectural Support for Programming Langugaes and Operating Systems, Newport Beach, CA, USA, 5–11 March 2011; pp. 265–278. [Google Scholar]

- Stephanie, F.; Thanh, V.N.; Westley, W.; Claire, L.G. A Genetic Programming Approach to, Automated Software Repair. In Proceedings of the 11th Annual Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computationm, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–12 July 2009; pp. 947–954. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Yang, J.; Tan, L.; Hafiz, M. R2Fix: Automatically generating bug fixes from bug reports. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation, Luxembourg, 18–22 March 2013; pp. 282–291. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Nam, J.; Song, J.; Kim, S. Automatic patch generation learned from human-written patches. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Software Engineering, San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–26 May 2013; pp. 802–811. [Google Scholar]

- QEMU. Available online: https://www.qemu.org/ (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- Halstead, M.H. Elements of Software Science; Elsevier North-Holland: New York, NY, USA, 1977; p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- DARPA Cyber Grand Challenge. Available online: http://archive.darpa.mil/cybergrandchallenge/ (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- Shudrak, M.O.; Zolotarev, V.V. Improving fuzzing using software complexity metrics. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Security and Cryptology, Seoul, Korea, 25–27 November 2015; pp. 246–261. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, B.; Smaine, M. A Chi-Square-Based Decision for Real-Time Malware Detection Using PE-File Features. J. Inf. Process. Syst. 2016, 12, 644–660. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.H.; Shin, H.S.; Nasridinov, A. A Comparative Study on Data Mining Classification Techniques for Military Applications. J. Converg. 2016, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, F.; Lindner, F.; Rieck, K. Vulnerability extrapolation: Assisted discovery of vulnerabilities using machine learning. In Proceedings of the 5th USENIX conference on Offensive Technologies, San Francisco, CA, USA, 8 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gustavo, G.; Guilermo, L.G.; Lucas, U.; Sanjay, R.; Josselin, F.; Laurent, M. Toward Large-Scale Vulnerability Discovery using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the Sixth ACM conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy, New Orleans, LA, USA, 9–11 March 2016; pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).