Abstract

China, as a non-Mediterranean country with non-Mediterranean climate, is taking olive cultivation as an important part of its agricultural development. In order to highlight some important facts about the history, status, distribution, and trends of the olive industry in China, we performed analyses based on Internet databases, online GIS software, and scientific papers. Results show that the olive industries have been concentrated in several key areas in Gansu, Sichuan, Yunnan, Chongqing, and Hubei. However, the business scope of olive enterprises is still narrow, the scale of enterprises is generally small, and individual or family management of farmers plays an important role. Thus, increased investment and policies are needed to enhance their capacities of R&D and production, and Chinese investigators should carry out socio-economic studies at the microcosmic level and take the initiative to innovate the products by cooperating with people in the same professions worldwide.

1. Introduction

Due to the well-balanced oil composition and the great commercial value of the olive (Olea europaea L.), many traditional and emerging countries have developed their olive industries, such as Spain, Italy, Greece, France, the USA, and Australia. With the expansion of olive cultivation areas, the development of emerging growing regions and traditional cultivated areas have attracted researchers’ attention, and it is clear that most of these regions have Mediterranean climates or belong to the Mediterranean area. However, it is interesting that China, as a non-Mediterranean country with non-Mediterranean climate [1], is taking olive introduction and cultivation, starting more than 50 years ago [2], as an important part of its crop introduction and agricultural development [3]. The FAO sees the introduction and development of olives in China as an exceptional experiment [4], which has been carried out on the fact that China is a vast country with a north–south latitude spanning of nearly 50°, resulting in a wide variety of ‘microclimates’. Therefore, it was expected to find some suitable growing areas in China for olive trees [5], especially in the western provinces of China, such as Gansu, Sichuan, Shaanxi, and Yunnan. However, from the perspective of rigorous academic research, the current situation of the development of the olive sector in China, and whether it can maintain itself in some sustainable way or promote the sustainable development of the Western China, has no clear answers. On a scientific level, from the 1960s to the 2010s very few studies have focused on olive industries in China from a macro and quantitative perspective since it is still in the early stages of development when compared with the Mediterranean countries. Thus, this paper wants to highlight some important facts about the history, status, distribution, and trends of the olive industry in China. Academics might be attracted by these facts when they approach the issue of sustainability with a specific focus on olive cultivation and industrialization in China.

2. History of the Olive’s Introduction to China

Olive trees were grown sporadically in China as early as the ninth century, most of which were brought back by missionaries and businessmen for ornamental usage without any economic benefit [6]. In 1956, the government of Albania sent 30 olive trees as a gift to China. These trees were introduced and cultivated in the big cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. Six trees were cultivated in the Nanjing botanical garden of Zhongshan, Chinese Academy of Sciences, where they have gone through the indoor and outdoor experiments, and three of them bloomed and yielded in 1963 [7]. This was regarded as the first introduction and cultivation of cultivated olive trees in Modern China. In November 1959, Mr. Zou Bingwen (1893–1985) recommended the introduction of olives to the Ministry of Agriculture based on his experiences in the FAO [8]. In Mr. Zou’s proposal, some important information might help us recognize the purposes or aims of China’s olive introduction. He mentioned the following points: (1) olive oil was the highest quality edible oil in the world and could be used as the main source of food; (2) after the October Revolution, the Soviet Union attached great importance to the development of olives; (3) the average yield of 787.5 kg/ha of olive oil in the Soviet Union was much more than the corresponding average yields of peanut oil (375 kg/ha) and soybean oil (270 kg/ha) in China in the 1950s; (4) the olive tree’s cold resistance was more outstanding than many other evergreen fruit trees, which means it can live in temperatures of −8 °C without any freezing injury; (5) olive trees are beautiful, with strong and adaptable wood, and could grow in arid and barren soils which are not suitable for many other crops; (6) the olive oil processing method is so simple that the small scale waterpower mills could be competent; (7) China is a big agricultural country endowed by nature with rich agricultural resources, which has a long history of farming and the tradition of intensive cultivation as well as a huge rural population that would be able to find a suitable place for olive trees. Mr. Zou’s proposal received the attention of the Ministry of Agriculture and the responsible officers quickly organized the relevant units to establish the working schedules for the olive’s introduction. The introduced germplasm resources included 1696 seedlings, 60 kg of seeds, and 202 cuttings. The introduction points were concentrated in the major cities of Kunming, Nanjing, Chengdu, Changsha, Nanchang, Guiyang, Wuhan, Hangzhou, Guangzhou, Xian, and Beijing. Mengzi County, Yunnan province and Miyi County, Sichuan province were the only small towns that received some of this germplasm. The introduction of this stage proved preliminarily that olives, a Mediterranean plant, could grow normally without serious cold or freezing injury. The success of the introduction test had become an important reason for the popularization of olives.

Prime Minister Zhou Enlai’s visit to Albania on 31 December 1963 is regarded as another cause of the large-scaled introduction of olive trees to China [9]. As a witness, Premier Zhou was impressed by the olive trees and their accompanying culture, which had been passed down from ancient mythology, as well as their miraculous efficacy in health care. Thus he decided to introduce olives in a large scale to China. On 19 January 1964, two senior technicians were sent to China with 10,680 strains and 4 varieties of olive seedlings on a special Albanian ship. When it arrived in Zhanjiang port on 18 February 1964, the olive seedlings were sent to eight provinces (districts) in the south of the Yangtze River. Most of the more than 10,000 seedlings were conducted experimental production in the National forest farms such as Haikou forest farm of Kunming. The provinces of Guangxi, Yunnan, Sichuan (including Chongqing) and Guizhou had undertaken the main production tasks, thus their introduced seedlings accounted for more than 90% of the total, and more than 80% of the seedlings were concentrated in the cities of Liuzhou, Guilin, Kunming, Chongqing, which were likely to be considered as the main production bases. The main introduction areas and the distribution of seedlings are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Seedling counts in the main introduction areas in 1964 1,2.

Since large-scale introduction in 1964, the cultivated areas have obviously expanded in China. From then on, led by the Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Forestry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and other national institutions, olive germplasm resources from Albania, the Soviet Union, and some Western countries have been introduced to China many times, and observational experiments—such as growth, drought resistance, cold resistance, disease, grafting, fertilization and irrigation—have been carried out. Since 1978, China has carried out step by step the policy of reform and opening up, bringing along a quickened pace in agricultural reform and development. Thus, more and more Chinese researchers have been sent to the Western countries—such as Italy, France, and Spain—to investigate their olive cultivation and industry. As a result, olive trees have been cultivated almost all over China’s Southern provinces and regions as well as in some Northern provinces such as Gansu and Shaanxi until 2017. Although the South of Gansu and the South of Shaanxi belong to the typical ‘south’ or the Yangtze River Valley in the view of geographical science, and their climate and vegetation have distinct southern characteristics, they were marginalized or even completely ignored in the introduction process in 1964. This phenomenon might reflect the complexity and diversity of the natural, cultural, and social environment in China. The advantages of soil and climate have finally made Longnan city, Gansu province become the most suitable area for olive cultivation in China. This success might rely on the spontaneous introduction of Shaanxi and the technological exchanges between Shaanxi and Gansu. Through the successful introduction of Hanzhoung, Shaanxi province and Longnan, Gansu province, olive trees have spread to the traditional or cultural northern regions and provinces of China. After more than half a century of introduction, Chinese researchers have found the suitable areas for olive production in China, and according to the differences of climate and soil conditions, these regions are divided into the primary and secondary suitable areas. Table 2 shows the suitable areas for olives cultivation in China. Table 3 shows the different major cultivars or varieties in the main grown areas of Gansu, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Chongqing.

Table 2.

Suitable areas for olive growth in China [11].

Table 3.

The main varieties of olives in China [12,13,14,15,16,17].

3. Status and Trends

In recent decades, the olive industry in China has been concentrated in several important regions in the suitable areas. Since 2006, Longnan city, Gansu province has become the largest olive cultivation and industrial base in China. By the end of 2009, the provinces could be ranked according to their cultivated olive areas as: Gansu, Sichuan, Chongqing, Yunnan, Shaanxi, Hubei, and Jiangsu. Besides Gansu, Sichuan and Yunnan also have realized their olive industrialization. In 2015, according to the output of olive fruit, Gansu, Sichuan, and Yunnan were the top three provinces in turn. It is known from Table 4 that in 2015, there were 65,600 hectares of olive trees planted in the above three provinces, and 37.4 thousand tons of olive fruits and 4902 tons of virgin olive oil were cultivated, which generated an income of 0.26 billion US dollars (based on the exchange rate in 2015) in the 39 counties.

Table 4.

Industrialization of olives in the main three provinces in 2015 [18].

In 1985, the first olive enterprise in China was established in Santai county of Mianyang city, Sichuan province [19]. By the end of 2015, there were more than 40 olive enterprises in China, and more than 20 virgin olive oil production lines were established. Traditional olive oil production methods—such as stone mill and direct mechanical extrusion, water press, and plate and frame filtration—have been very rare in China. However, crushing, fruit pulp mixing, centrifugal decanting, and centrifugal separation technologies have been widely used in olive processing in China. In particular, centrifugal dip technology includes three-phase and two-phase centrifugal systems. The three-phase centrifugal system is the most commonly used method in the intensive production areas such as Gansu, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Chongqing. In this process, grated olives are released directly into a three-phase separator. Water, oil, and pomace are separated. The main drawback of this method is that a lot of water is needed. The two phase centrifuge system, also known as an ‘ecosystem’ for the grated olives, can be separated in a two phase centrifuge (oil and pomace), which might reduce the consumption of fresh water and eliminate the production of waste water. Thus, this process has been used in some demonstration areas such as Longnan, Gansu. In order to describe the new changes since 2016, we got the data of olive enterprises in China through the Internet and analyzed their regional distributions. The data source websites included: Baidu enterprise credit (BEC), TianYan Cha (TYC), QiXin Bao (QXB), the National Enterprise Credit Information Publicity System (NECIP), and the National Administration for Code Allocation to Organizations (NACAO). The interactive query platforms of the above five websites were used to get the preliminary results, which are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Preliminary results of the olive industry and related organizations in China

The main research objects were the province, municipality, and autonomous region. The results did not contain data from Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. After the irrelevant and repeated records were excluded, it was found that there were 2825 olive enterprises in China by January 2018, and 2459 of them were in operation. The Beijing Shenzhou Olives Technology and Development company, founded in 1988, might be the oldest enterprise in operation according to its registration time, which is a scientific and technological enterprise initiated and controlled by the Chinese Academy of Forestry Sciences.

3.1. Time Trend

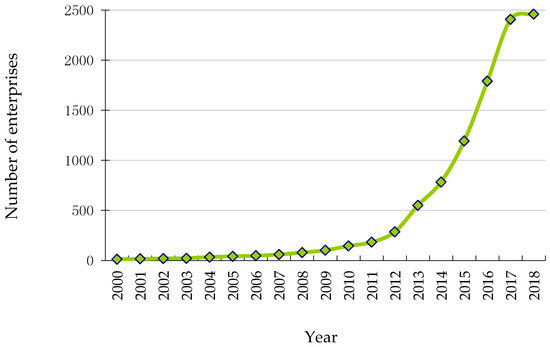

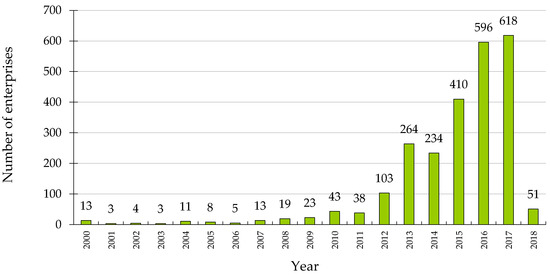

There are only 12 enterprises which were established before 2000 (excluding 2000). Among them, six were in Gansu; three were in Sichuan; one was in Shandong, Yunnan, and Beijing respectively. In the period of 2001~2008, the annual number of new registered enterprises was below 20, and the growth was also slow. Since 2009, olive enterprises in China have been increasing significantly, especially in the last five years since 2012. In 2012, the number of newly registered enterprises exceeded 100, and in the following two years, more than 200 new registrations have been made annually. In the three years of 2015~2017, 410, 596, and 618 enterprises were added in each year. Since the olive industry has been supported by the governments of Western provinces in recent years, 92.56% of the existing enterprises were registered after 2012. In 2016 and 2017, the number of registered enterprises reached 1214, accounting for 49.37% of the total. There were 286 enterprises in operation for more than five years, accounting for 11.63% of the total; and 60 enterprises have been in operation for more than 10 years, accounting for 2.44% of the total. Figure 1 shows the annual growth of the number of olive enterprises in China. Figure 2 shows the registration time distribution (data in 2000 includes previously registered ones).

Figure 1.

Annual trend of the number of the olive enterprises in China.

Figure 2.

The distribution of the registered years of the olive enterprises in China.

3.2. Types and Businesses

Among the 2459 enterprises, there are five corporations (joint stock companies); 28 private associations; 582 limited liability companies (LLC); 1342 partnerships; and nearly 500 family farms, planting bases, and other sole proprietorships (SP). The number of the partnerships and the SP is about 1800, accounting for nearly 75% of the total business entities. No quoted companies were found. It is seemed that the sizes of the olive enterprises in China are generally small and that household management has played an important role in olive growing regions. Only three companies of Garden City, XIANGYU, and Enlai have respectively opened their offices or branches in Beijing, Shenzhen, and Guangzhou. The companies of Garden City and XIANGYU have established their O2O marketing channels through Tmall.net and Jingdong.net. However, most of the other enterprises have not yet made obvious distribution channels across the whole country, and their offices or branches are mostly within their provinces, indicating that these enterprises have not formed any cross-regional collaboration networks.

The businesses are concentrated in seedling cultivation and seedling sales, and only a few companies are engaged in the production of olive oil and related products. There are 1459 enterprises engaged in olive planting, 852 engaged in seedling cultivation, 108 engaged in olive oil production and operation, and only 69 engaged in olive cosmetics and skin care products. There are 144 enterprises that have developed the olive tourism based on their farms or forests. There are 119 enterprises whose registered capital was more than 20 million Yuan (3.17 million USD) (Figure 3). Among them, 62 enterprises are in Gansu, accounting for 51% of the total. This reflects that Gansu’s olive investment has been at the forefront. Some enterprises in Gansu province have begun investing in other olive growing areas such as Yunnan and Sichuan.

Figure 3.

Distribution of enterprises whose registered capital is more than 20 million Yuan (3.17 million USD).

In China, a corporation (joint stock company) is generally regarded as a public company because of the large amount of its investment (at least more than 793.65 thousand USD) and the relatively large holders (not restricted by 50 persons). Thus, the number and businesses of the corporations might reflect the olive industrialization process in China. There are five corporations in olive cultivation and the related investments, products, and services. Among them, Yunnan Supply & Market E-commerce (SME) and Jin Feng Hui Oils & Fats (JFH) belong to Yunnan province; Green Lustre Fruit and Vegetable (GLFV) is in Gansu; Ruifu Sesame Oil (RSO) is in Shandong; and China Oil Agriculture (COA) is in Zhejiang (Table 6).

Table 6.

Olive corporations (limited by share) in China.

SME is the only e-commerce company among the five corporations, which belongs to the Yunnan Supply and Marketing Cooperative Union. This organization was founded by the Yunnan government and its agricultural leading enterprises; SME has built its e-commerce platform named “Cloud Commodity” and is operating the “cloud supply and marketing” shop on Taobao network. SME provides tea, fungus, fruit, Chinese traditional medicinal materials, vegetables, and dried fruits to consumers. However, there are no olive-related commodities in the website of SME, indicating that olive are only a small part of its business planning, the corresponding products or services are still lacking. JFH, RSO, and COA are engaged in oils and fats and the related products, while GLFV is engaged in fruits and vegetables and other agricultural products. JFH mainly deals in rapeseed oil and soybean oil, whose brand of ”Jincaihua” is a blended product of olive and rapeseed, not including virgin olive oil. RSO mainly produces small mill oil, and its olive business involves the filling, packing, and sales of the imported olive oil, which has little relationship with the olive growing or development areas in China. COA originally produced and sold some plant seedlings. The edible oil and the olive cultivation were included in its main business after 2015. GLFV owns two olive brands—Green Lustre Manor and Dai Shi Na—but the products of these two brands were not popular. It is undoubted that although the above five corporations have their relatively larger registered capital, their olive-related products or services are extremely limited.

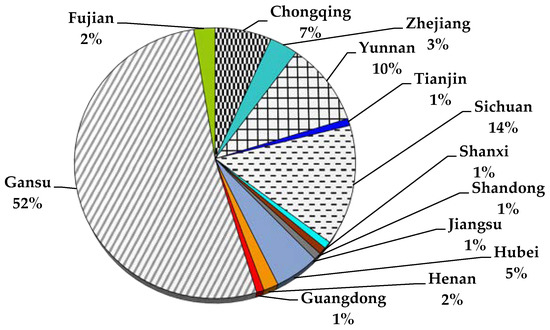

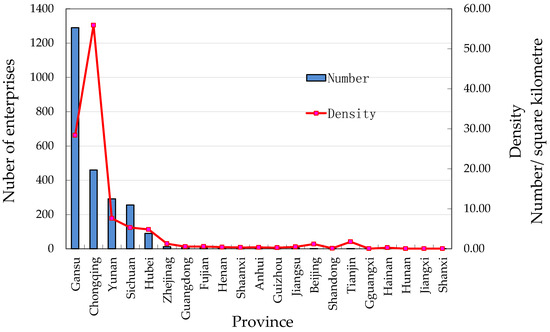

3.3. Distribution and Density

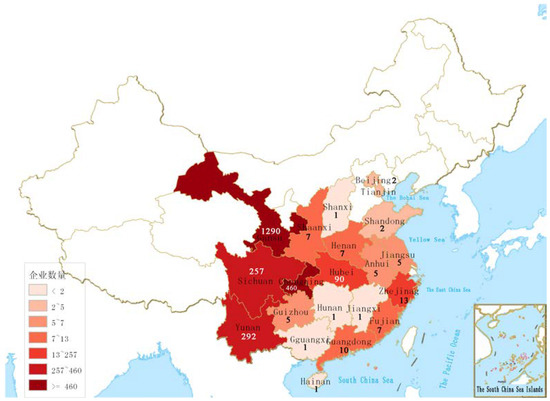

As shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, the olive enterprises in China are mainly distributed in Gansu, Chongqing, Yunnan, Sichuan, and Hubei. All of the top five provinces have 2388 enterprises, accounting for 97.11% of the total throughout the country. There are 1290 olive enterprises in Gansu province, accounting for 52.46% of the total, showing a strong regional concentration. There are 460 enterprises in Chongqing, accounting for 18.71% of the total. With a larger amount of registered enterprises than Sichuan and Yunnan, Chongqing has become one of the important regions in the olive development. The density of enterprises in Chongqing is 55.89/km2, which has exceed the record of Gansu (28.39/km2), ranking the first in China. The distribution of the enterprises has a strong consistency with the cultivated area and the amount of fruit production, which indicates that due to the olive fruit needing to be processed in time after its harvest, the related enterprises are mostly distributed in their planting and producing areas when facing the lack of cold storage for fresh olive fruit in China.

Figure 4.

Distribution and density of the olive enterprises in China.

Figure 5.

Distribution map of the olive enterprises in China.

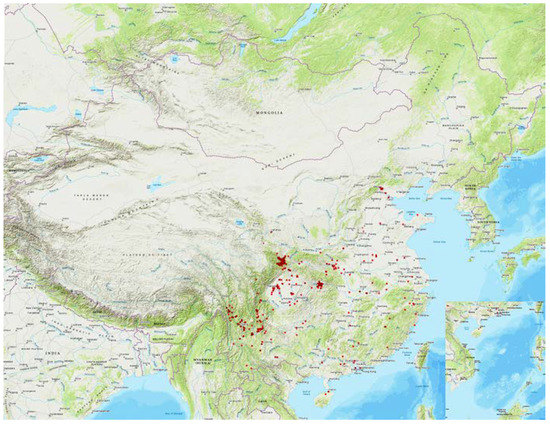

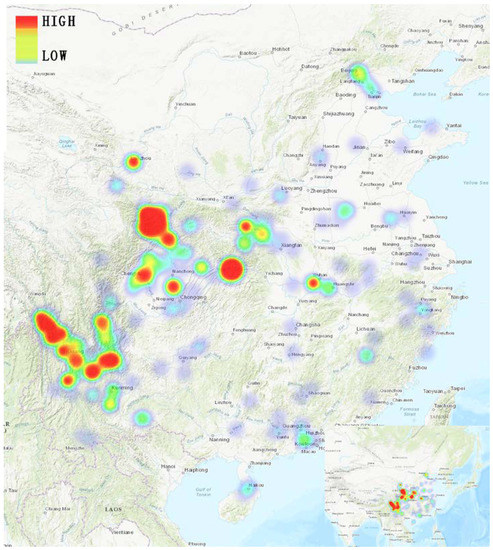

The registered addresses of the enterprises were converted to latitude and longitude, and the converted data were presented in a scatter point through the GeoHey GIS software (https://geohey.com/) and visualized by the thermal map. The results are shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7. The geographical distribution of the olive enterprises is both extensive and concentrative, and has the following characteristics: (i) olive enterprises have been distributed in the 21 provinces, municipalities, autonomous regions, and chartered cities in north and south China. (ii) nine centralized hot areas of olive development have been formed in China, they are (1) Lanzhou, Gansu; (2) Longnan, Gansu and Guangyuan, Sichuan; (3) Chengdu and Mianyang, Sichuan; (4) Nanchong, Sichuan and Chongqing main city; (5) Northeast of Chongqing; (6) Lijiang and Diqing, Yunnan; (7) Chuxiong, Yunnan; (8) Liangshan, Sichuan; and (9) Shiyan, Hubei. Among them, Lanzhou, Chengdu and Chongqing are large cities; the other regions are located in the Qinba mountain area, Jinsha river dry hot valley, Sichuan hilly area, and other poverty-stricken or minority areas. (iii) Enterprises in Lanzhou and Chengdu are more concentrated. Enterprises in Chengdu are mainly concentrated in the main urban area and the Jintang County, located in the east of Longquan Mountain. Enterprises in Lanzhou are mainly concentrated in its main urban area too. Compared with other capital cities such as Kunming, Wuhan, and Chongqing, the number of enterprises in the above two cities is obviously higher. In recent years, the development of enterprises in Mianyang, Deyang, and Ziyang near Chengdu has also been rapid, which has become the representative of the olive industry in a megacity city and its surrounding areas. In the above 9 areas, olive companies are further concentrated in 11 places. They are Longnan of Gansu; Shiyan of Hubei; Mianyang, Panzhihua and Liangshan, Guangyuan, Dazhou, and Chengdu of Sichuan; Lijiang, Chuxiong, and Diqing of Yunnan; and the province-level municipality of Chongqing. The distribution of the olive enterprises in the above 11 areas is shown in Table 6.

Figure 6.

Scatter point map of the olive enterprises in China.

Figure 7.

Thermal map of the olive enterprises in China.

From Table 7, we can see that the distributions of the olive enterprises in Chuxiong, Longnan, and Chongqing are very concentrated. The number of enterprises in Longnan is not only ranked first, but also far exceeds the total of the other 10 regions, reaching 1250, and its olive industry is mainly concentrated in Wudu area. Wudu alone has 1148 enterprises, the other 2 counties of Wenxian and Dangchang in Longlan have 80 and 18 companies respectively.

Table 7.

Distribution of olive enterprises in the typical 11 areas.

Chuxiong has 62 enterprises, which are mainly distributed in Yongren County (61). The total development area of Yongren county is about 7600 hectares, and its olive industry has been strongly supported by the government in Yunnan. Before 2010, the first large-scale planting base in Yunnan had been built in Yongren, with an area of about 133.3 hectares. In 2015, the planting area was expanded to more than 1300 hectares, and about 6600 hectares of planting area in the future of 2020 were planned. Most of the olive enterprises in Yongren are family farms, planting bases, and other sole proprietorships. Thus, the development of Yongren needs to further strengthen the role of the leading enterprises. Diqing is another one key area of poverty alleviation in Yunnan, thus there are more than 100 olive businesses in this area, but their scales are generally small.

The enterprises in Chongqing are concentrated in nine counties. The number of the total is 454. Among them, 417 are located in Fengjie County, and another 27 are registered in Hechuan County. The local government of Fengjie planned to develop 10,000–13,000 hectares of olive forest, and has completed the development of 1500 hectares by 2017. There are 38 enterprises in Chengdu, and 33 of them are registered in Jintang County. The olive development of Chengdu is characterized by a comprehensive development of agricultural tourism. In recent years, the planning and construction of the Tianfu new area has attracted the olive planting into the Shuangliu, Hua Yang, and other counties in the Tianfu new area, but their development goals are not to produce olive oil, but to form landscape or scenery by planting olive trees and other ornamental flowers and trees, and building traditional European architectures. As a typical area for the development of olive industry around a megacity in recent years, Jintang county has gradually taken the road of comprehensive development of the olive rural tourism, olive culture, and olive oil processing experience, relying on Chengdu’s huge tourist market. Jintang has planned to develop olive growing area of about 6600 hectares, and by 2017, it has achieved about 3000 hectares.

The enterprises in Dazhou, Sichuan are mainly concentrated in Kaijiang and Xuanhan County, and the number of the enterprises is relatively small, with a total of 11. Six of them are in Kaijiang and the other five enterprises are in Xuanhan. Guangyuan and Mianyang are closely related in Sichuan. The number and distribution of olive enterprises in these two places is also very similar. However, Guangyuan has become the key object of the overall planning of poverty alleviation in the Qinba Mountains and Daba Mountains in recent years because of the high pressure on poverty alleviation in the local mountainous counties, such as Qingchuan. Therefore, the number of the olive enterprises in Guangyuan is more than that of Mianyang. The enterprises in Mianyang mainly concentrated in its main city area of Youxian and the Santai County. Led by the local leading enterprises, an annual production and processing capacity of more than 3000 tons of olive oil has been formed in Mianyang. Panzhihua and Liangshan are the most important introduction and development zones for olives in Sichuan as they have a large suitable area for olive cultivation. The introduction and development of olives in these two areas not only has a long history, but also plays an important role in local poverty alleviation. Thus, the policy support is great, which results in a relatively large number of counties involved in the development of olive.

It is interesting that the number of the enterprises in Lijiang and Shiyan is equal to 74. Furthermore, Lijiang has been supported by the industrial capital and technologies from Longnan, Gansu. Gansu’s Garden City Co., Ltd., one of the leading enterprises in Longnan, has completed its capital output in Lijiang, and has registered and put into operation the two branches of Lijiang Garden City and Shangri-La Garden City. The experience, capital, and technologies from Gansu, combined with the local policies and the important geographical location of Lijiang, might be expected to lead to the further development of olive, driven by the consumption of its famous leisure tourism. Shiyan is located in Hubei Province and the introduction and development of olive tree in Hubei is early, and the experience accumulated in Hubei is expected to play an active role. Shiyan has a geographical position in Qinba mountain area, thus it is now regarded as the ‘new continent’ of olive developing outside of Sichuan, Yunnan, and Gansu.

3.4. Development Potential

According to the land resources needed for olive development, there are some limitations in the development of olive industry in Wudu County of Longnan city, Gansu province. The land suitable for planting olives in Longnan is rather limited to its low elevation area along the Bai Longjiang River. There are about 19 thousand hectares suitable for olive trees in Wudu, and the total area of the entire Longnan is about 20 to 30 thousand hectares. Even with the development of the very limited suitable land in the Kang County and the Li County, the total area of the suitable development of olives in Longnan is also difficult to exceed 50 thousand hectares. By 2017, the area of olive planting in Longnan has reached 40 thousand hectares [20]. In order to meet the needs of a variety of operations, some land will continue to be planted with pepper and other economic crops, so the actual planting area will be lower. Longnan’s olive industry, due to the limit of the scale of the land, will be developing towards the direction of optimizing the product structure and improving the brand. The further improvement of olive industry in China might require the development of other regions especially Liangshan, Dali, Chuxiong, and Lijiang along the dry and hot valleys of the Jinsha River. An overview of the potential of olive planting in the main districts and counties is shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Potential of olive planting in the main districts and counties.

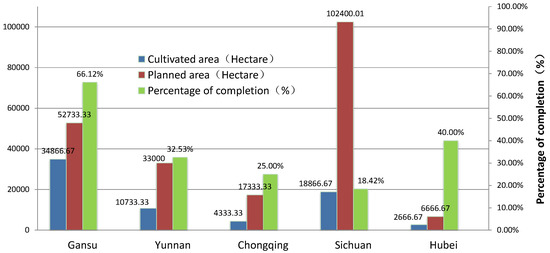

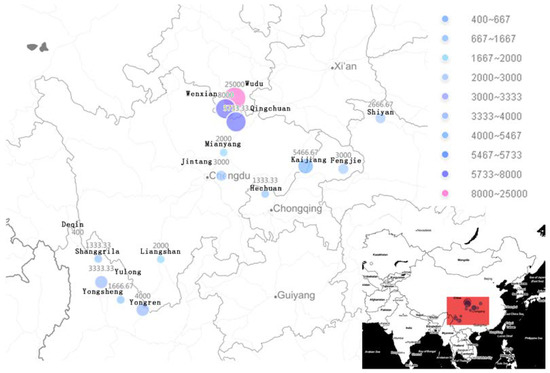

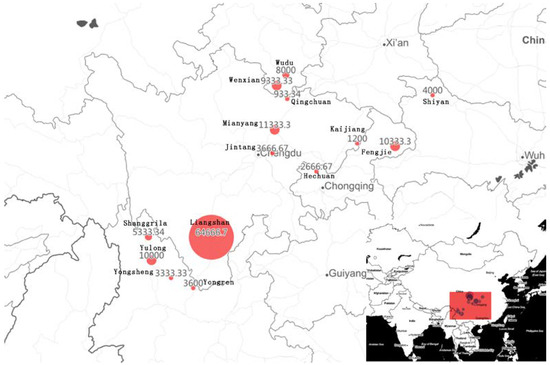

According to Table 8, the planting area of olives in these 17 districts has exceeded 70 thousand hectares, which accounts for 33.75% of the total planned area for more than 206 thousand hectares in the next few years. Among them, the development degree of Qingchuan, Wudu, and Kaijiang Dangchang is at the highest level, reached 86, 82, 75.76, and 77.78%, respectively. Wudu is very close to its development limit, and the increase in the area of future olive planting in Longnan might depend mainly on Wenxian. The other main planting areas, except Longnan, ranked according to the relative development potential (unfinished percentage) are: Liangshan > Mianyang > Shangri-La > Fengjie > Yulong > Li Zhou > Hechuan/Yongsheng > Shiyan > Jintang > Wenxian > Yongren. The main planting areas ranked according to the absolute development potential (unfinished planned cultivation area) are as follows: Liangshan > Mianyang > Fengjie > Yulong> Wenxian > Wudu > Shangri-La > Shiyan > Jintang > Yongren > Yongsheng > Hechuan > lizhou > Kaijiang > Qingchuan > Dangchang. Liangshannn, Sichuan province is the most promising area for olive production and processing. Yulong and Fengjie also have the great potential for future development. Although Shiyan, Jintang, Wenxian, and Yongren have completed 40–50% of their total planned areas, they still have considerable potential for planting and development because of their large planned or growing area. Furthermore, Figure 8 shows the relative development potential (unfinished percentage) of the main provinces: Sichuan > Chongqing > Yunnan > Hubei > Gansu, as well as the absolute development potential (unfinished planned cultivation area) ranking: Sichuan (83,533.34 ha) > Yunnan (22,266.67 ha) > Gansu (17,866.66 ha) > Chongqing (13,000 ha) > Hubei (6666.67 ha). The geographical distributions of the cultivated areas and the potentials are also shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 8.

The status and potential of olive planting in the main provinces.

Figure 9.

Distribution of the cultivated areas (hectares) in the main districts and counties.

Figure 10.

Distribution of the non-planted planned areas (hectares) in the main districts and counties.

In recent years, Chinese researchers have done some work about the quality, yield, and their relationship identification for the introduced varieties and locally bred varieties [21]. Olive mill wastewater (OMW) arises from the production of olive oil in olive mills. It is produced seasonally by a large number of small olive mills scattered throughout the olive oil-producing areas [22]. Chinese researchers attempted to solve this problem by making olive wine [23,24]. The corresponding products have been produced and gained benefits in the local market of Gansu and Sichuan province [25,26]. As olive trees were planted in the subtropical and temperate monsoon climate regions of China, their fruit oil content is usually lower than those of Mediterranean origin, but the volume of fruit, the pulp rate, and content of the olive polyphenols were relatively higher [27]. Therefore, the comprehensive development of table olive, oil, and leaf has gradually become the consensus of the Chinese olive industry and academic circles in recent years. However, as table olive cultivation and deep processing has become an internationally modernized industry, the related scientific output is so abundant and the product is very rich; but for Chinese consumers, table olive products are extremely limited and less. According to the statistics of International Olive Council, China has an annual olive oil import of 30,000 to 40,000 tons, which far exceeds the import of table olives [28,29]. This is mainly because foreign table olive products are mostly slightly salty pickles with a soft mouth-feel, which does not completely satisfy the demands of Chinese consumers. Through the Chinese Journal Full-Text Database (CJFD), we found that studies on olives in China date back to 1964. The SCI papers from China that report olive studies date back to 2001 [30], but the number of papers has increased at a relatively low rate. During the past few years, the number of research papers involving olive trees and olive oil has increased significantly to cater to the increased demand in the olive market due to the interests shown by Chinese consumers for Mediterranean diets as well as the wide-scale acceptance of Western-style foods. However, the SCI papers published by Chinese scholars have just mainly focused on the introduction and the cultivation of olive trees as well as the extraction of valuable pharmaceuticals, the identification of olive oil, and organic components, rarely involving specific processing issues. The SCI papers from China mainly involved the following four aspects: (1) introduction and cultivation, (2) pharmaceutical value, (3) component analysis, and (4) social events. In spite of some increase in the recent number of domestic research papers, most of the research results for planting and product processing of olives in Chinese monsoon climate regions are abundant. However, most of them were not translated into other languages such as English and were not submitted to any international journals. If they were written in English, more researchers might be concerned about the progress of Chinese research and development of olives. In 2016, China’s Olive Industry Innovation Strategic Alliance (COIISA) was founded, which might facilitate the exchange and cooperation of Chinese research institutions with authoritative bodies such as the International Olive Council [31].

As most of the scientific output concerning olives in China has been published in Chinese journals, their content is often related to rural poverty alleviation and prosperity and their topics have included: (1) market and policies, (2) introduction and cultivations, (3) international exchange, (5) olive fruits, olive oil, olive cannel, olive wine, table olive, as well as the comprehensive benefit such as intercropping and breeding and even olive eggs (from a hen who has eaten olive fruit). In the future, more studies might be needed on fruit harvesting. With the expansion in olive cultivation areas in China, the focus of studies might shift from introduction and cultivation to harvesting and processing.

5. Discussion

Since the 1964 introduction and development of olives in China, more than 60 years have passed. Before 1964, the experimental introduction areas were concentrated in the cities of Nanjing, Kunming, Chengdu and some other provincial capital cities. In 1964, the planned large-scale productive introduction was concentrated in Liuzhou, Guilin, Kunming, Chongqing, Dushan, and other places in the southwest regions of China, it has since expanded to 15 provinces, chartered cities, and autonomous regions in the south and north of China. If we compare the introduction process of olive and other crops—such as pumpkin, watermelon, and capsicum—in China, the main features of the introduction and development of olives could be found as the follows: the sources, targets, and routes of olive germplasm resources are clearly distinguishable; the planned introductions had been supported by the power of modern sciences and technologies accompanied by top-down cultural communication and political propaganda, which showed or annotated the national strength of the New China and had the symbolic meaning of national integration; the selection and distribution of the introduction points in the plan were obviously attached to the southern provinces and avoided the northern ones, but the spontaneous technological diffusion between regions has countered this tendency. As an example, Shaanxi and Gansu were not in the planned areas in the large-scale introduction in 1964. However, the spontaneous introductions in Shaanxi and the spontaneous technology diffusion and cultural exchange between Shaanxi and Gansu were the important reasons leading to the emergence of Gansu later. From big cities such as Nanjing, Beijing, and Wuhan to the western counties such as Wudu, Yongsheng, et al., there have been obvious regional changes and evolutions in such a long period of olive cultivation and development in China. However, studies on this history and the differences and causes between different regions are relatively limited, though they are so obvious. In order to explore the reasons of regional differences and seek methods leading to more efficiency, more studies on the regional changes should be carried out. The main driving forces and resistances to the introduction and development of olives in China should be summed up too.

According to our analysis, the introduction of olive trees in China has experienced its evolution for more than half a century, but most of the olive growing areas in China are still at the initial stage of agricultural industrialization, especially when talking about the scales of the olive enterprises and their products. As an economic crop, olive oil or table olives lacked normal trade and consumption channels in China before 2000, and the consumption of olive oil and other related products in China was also very limited for such a long time. Thus, olive planting was disastrous in the 1990s because it could not produce enough benefits for the farmers, and especially could not bring short term economic benefits. Since the implementation of the policy of reform and opening up in China, especially since the beginning of this century, the industrialization development of olives in China has changed from the initial comprehensive promotion to the key development in the western areas because of stimulus from the imported olive oil. Most of the cultivation seedlings and the production of olives has been concentrated in several important areas in Gansu, Sichuan, Yunnan, Chongqing, and Hubei and has contributed to local poverty alleviation and development. However, the business scope of the olive enterprises in these areas is still narrow, which was concentrated on the cultivation and sales of seedlings. Though there are many enterprises engaged in fruit transportation and picking, the number of enterprises engaged in olive oil and its related products is very less; the scale of enterprises is generally small, and the individual or family management of farmers still plays an important role in China’s olive industry. Thus, increasing investment and policies are needed to enhance their capacities for R-&-D and production, as well as the corresponding services. It is fortunate that a few enterprises in Longnan city, Gansu province have begun to invest in planting areas in Yunnan and Sichuan to achieve a multi-channel acquisition of expanded production and olive fruit, which might bring the technology, experience, and lessons of Longnan to other areas in western China.

It is undoubted that in the western provinces or regions of China—such as Gansu, Sichuan, Shaanxi, Yunnan, Chongqing, and Hubei—olive cultivation has been used as a corresponding method of the policy of poverty alleviation and as a result, various enterprises of different sizes have been established to gain market benefits. However, when talking about olives, which are as equally important as wine in Mediterranean agriculture and culture, many Chinese consumers only know that it is some plant or tree which can provide olive oil. Furthermore, they might directly express their dislike of table olives because of their flavor, and most Chinese consumers could not recognize the differences between Chinese olives (Canarium album (Lour.) Raeusch.) and olives (Olea europaea L.), even though they are more and more enjoying olive oil as it can bring them health and good flavours. In fact, China has a long history of pickle processing as well as a strong culture of fermentation and brewing. Consumers do not feel strange about the healthful fruit pickle, such as table olives, even though they come from Mediterranean countries, but it is necessary to modify the Chinese consumer’s characteristics according to their preferences and to carry out studies on marketing. Studies in China, based on the recognition that Chinese consumers favor sweet fruit products, successfully developed table olive products with Chinese characteristics, such as olive wine, candied olives, olive dairy products, olive jam, and sour and sweet fermented olive fruits. However, few comprehensive and systematic studies have been carried out on these products, and the market feedback has also been limited. The lack of knowledge of olive products for Chinese consumers might be attributed to the lack of industrialization and its related research. By the end of 2017, no domestic study has focused on the business process management (BPM) or life cycle assessment (LCA) of olive production, or producer/consumer decision-making and marketing, which is somewhat associated with the scale of production and processing enterprises and the regional limitations, and is an indication that the production and value chain studies are insufficient. Therefore, more effort needs to be applied to studies on these fields and related microeconomic and market studies are needed too.

China, as a non-Mediterranean country, has introduced and cultivated olives successfully, which has been regarded as an achievement in the world history of varietal introduction. However, there is still a huge gap in the scale of production, product quality, and marketing between China and Mediterranean countries. Mediterranean countries, the EU, and the USA are the three major forces in olive R&D. In terms of olive production and corresponding culture, the Mediterranean countries stand out; production from Spain, Greece, and Italy are in the top in terms of extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) [32], and the Spanish cultivation areas and production have ranked first in for such a long time. As far as the table olive is concerned, some non-Mediterranean countries such as the USA have played an important role in the olive trade, which somewhat indicates the relatively high quality of their research topics and achievements, and their experiences are worth emulating for Chinese researchers. It is also interesting that the US is faced with a similar bottleneck to China during the promotion of olive planting and industrial expansion due to its monsoon climate (such as in Georgia and Florida), so it is worthwhile for Chinese developers and scholars to communicate with their American peers and learn from their development and research experiences. In recent years, international olive studies have paid more attention to the fields of product processing, sustainability, and olive tourism [33]. In the 10 years of 2004~2014, China’s olive oil imports increased by 792% and maintained an annual growth rate of 10% [34]. With the growth of China’s economy and the increase of the residents’ income, the Chinese consumption group of olive oil might further expand and become a big consumer of olive oil in the near future. IOC has made statistics on the product types of olive oil imported to China. It was found that China’s olive oil products were mainly imported from Europe. Extra virgin and virgin olive oil accounted for about 78% of the total import of olive oil in China, and about 8% was the ordinary olive oil and 14% was the pomace oil. At the same time, Chinese olive oil production has improved. According to the records of IOC, China produced about 5000 tons of extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) and virgin olive oil (VOO) in 2015~2016, which increased by 75% over 2014~2015. However, olive oil in China only accounts for about 1% of the total consumption of nearly 30 million tons of edible oil per year. The worldwide consumption of olive oil is about 2~3% of the total consumption of nearly 100 million tons of edible oil, of which EVOO accounts for about 1.8%; therefore, if the consumption of olive oil in China reaches 50% of the world’s average level (accounting for 1~1.5% of total edible oil), China will consume about 300 thousand tons to 450 thousand tons of olive oil per year. If the world average is reached, it needs to consume about 600 thousand tons of olive oil per year. As a non-Mediterranean region and a non-Mediterranean climate country, China is not only one of the importers of olive oil, but also a growing country for the cultivation and industrialized development of olive oil. Thus Chinese investigators should carry out socio-economic studies at the microcosmic levels and take the initiative to innovate the products by cooperating with people in the worldwide olive indutry. This will allow them to tap the potential of Chinese consumers for olives and to develop the Chinese olive industries for use of the oil, fruits, and leaves. With the further deepening of Chinese people’s understanding of olives and their function and culture, Chinese society is expected to bring about innovations in consumption concepts, research methods, development ideas, production methods, and health standards through the consumption and study of olive oil and its related knowledge. China’s olive oil markets and olive industries might both have a bright future.

6. Conclusions

China’s introduction of olives has spanned more than half a century. As a result, some western provinces such as Gansu, Sichuan, Yunnan, Shaanxi, Chongqing and Hubei succeeded to develop their olive industries, and the olive sector began to play an important role in the economic and social development of western China. However, the planting areas of olives in China have changed significantly. The experimental introduction sites before 1964 were distributed in the big cities along the Yangtze River. After 2001, olives’ cultivation and industrialization were concentrated in some western provinces. Nine centralized hot areas have been formed in China. In these 9 areas, Olive companies are concentrated in 11 places. As Wudu County, Gansu province is very close to its development limit, the increase in the area in the future in Gansu will depend mainly on Wenxian county. The other main planting areas except Longnan ranked according to the relative development potential are: Liangshan > Mianyang > Shangri-La > Fengjie > Yulong > Li Zhou > Hechuan/Yongsheng > Shiyan > Jintang > Wenxian > Yongren. The main planting areas ranked according to the absolute development potential are as fellows: Liangshan > Mianyang > Fengjie > Yulong> Wenxian > Wudu > Shangri-La > Shiyan > Jintang > Yongren > Yongsheng > Hechuan > lizhou > Kaijiang > Qingchuan > Dangchang.

Author Contributions

J.S. and C.S. conceived and designed the research; J.S. and W.Z. analyzed the data; L.P. contributed analysis tools; J.S. and C.S. wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the International Cooperation Project of Sichuan Provincial Science and Technology Department, P.R.C (2013HH0017) and the Youth Program Special Fund of Central Colleges and Universities Basic Scientific Research Expenses of the Southwest Minzu University (2017NZYQN21).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dias, L.B.M.P. Internationalization Process of Gallo Worldwide: Introduction of Olive in a Non-Traditional Market—China. Ph.D. Thesis, NSBE-UNL, Omaha, NE, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.A.; Liu, L.; Gu, Y. Olive Introduction and Breeding in China. I. The Theory and Practice of Olive Introduction in China. Riv. Ortoflorofrutticoltura Ital. 1981, 65, 413–432. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K.Z.; Xiao, Q.W.; Liang, M.C.; Jia, R.F.; Zhang, L.; Wei, L. Investigation and Analysis on Development Situation of Olive in Qingchuan County. Nonwood For. Res. 2007, 25, 117–119. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bourdellès, J.L. The olive-tree in People’s Republic of China. Introduction and development: an exceptional experiment. Hommes Et Plantes 2002, 11, 11–19. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, C.; Xu, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, T.; Yang, Z.; Ding, C. Quality, composition, and antioxidant activity of virgin olive oil from introduced varieties at Liangshan. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 78, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Z.; Chen, Q.; Luo, J.J.; Bai, X.Y.; Wang, Y.; Kong, L.X. Development and Industrial Prospect of China’s Olive. Biomass Chem. Eng. 2013, 47, 41–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.Z. Review and Prospect of Introduction and Development of Olives in China; China Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2010; pp. 17–20. ISBN 978-7-5038-6054-6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y. Development of edible woody oil industry in China based on olive introduction. Nonwood For. Res. 2010, 28, 119–124. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiburenzhe. The 50th Anniversary of Commemorating Prime Minister Zhou Enlai’s Introduction of Olive. Available online: http://www.360doc.com/content/14/1026/12/493864_420025708.shtml (accessed on 31 October 2017). (In Chinese).

- Li, J.Z. Review and Prospect of Introduction and Development of Olives in China; China Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2010; pp. 28–46. ISBN 978-7-5038-6054-6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W. Olives and Their Cultivation Techniques; China Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2010; p. 47. ISBN 7-5038-3814-0. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kong, W.; Li, W.; Xing, W.; Dong, M.; Rui, H.; Wei, Z. Research on the fruit quality of the main cultivated olive varieties in wudu district. J. Chin. Cereals Oils Assoc. 2016, 31, 87–92. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.J.; Chen, B.; Yeng, X.J.; Lan, L.; Wu, B.L.; Chen, T. A preliminary report on introducing Olea europaea in Jintang county located in the low hilly region of Longquan mountains. J. Sichuan For. Sci. Technol. 2013, 34, 84–88. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L. Study on the Photosynthetic Characteristics of Liangshan Introduced Olive (Olea europaea L.) Cultivars. Master’s Thesis, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu City, Sichuan Province, China, May 2016. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Na, H.E.; Li, Y.J.; Ning, D.L.; Ting, M.A.; Xiao, L.J. Evaluation on drought stress tolerance of six olive varieties cultivated in Yunnan. J. West China For. Sci. 2013, 42, 107–110. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 20 Thousand Mu Olive Harvesting in Fengjie County, Which Is Expected to Earn More than 4 Million Yuan. Available online: http://cq.qq.com/a/20161108/014505.htm (accessed on 17 April 2018). (In Chinese).

- Discussion on the Cultivation and Management Technology of Olive in Fengjie County. Available online: https://wenku.baidu.com/view/2212e60ab6360b4c2e3f5727a5e9856a561226ad.html (accessed on 20 April 2018). (In Chinese).

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J. Prospects Expectation for Development of Oil Olive Industry Development in China from the Domestic and Foreign Olive Oil Market. North. Hortic. 2017, 18, 184–191. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.Z. Review and Prospect of Introduction and Development of Olives in China; China Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2010; p. 96. ISBN 978-7-5038-6054-6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z.; Tian, M.; Wang, B. Olive in Wudu Mountain: Growth Meteorological Condition and Suitable Climate Division. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2016, 31, 161–166. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Zhan, M.; Yang, Z.; Zumstein, K.; Chen, H.; Huang, Q. The Major Qualitative Characteristics of Olive (Olea europaea L.) Cultivated in Southwest China. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 5958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paraskeva, P.; Diamadopoulos, E. Technologies for olive mill wastewater (OMW) treatment: A review. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2006, 81, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Gang, H.; Guo, X.; Hu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Gou, X. Antioxidant activity of olive wine, a byproduct of olive mill wastewater. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 54, 2276–2281. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Guo, Z.; Cai, G.; Ye, Z.W. Development of Twelveridge Chiner Olive Wine. Liquor-Mak. Sci. Technol. 2013, 41, 82–84. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, T.Z.; Ying, L.I.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.F.; Sheng, W.J.; Zhu, X.; Han, S.Y. Volatile Compound Analysis of Olea europaea L. Wine. Food Sci. 2014, 35, 161–166. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.M.; Li, J.T.; Wu, X.Y.; Shu, J.X.; Cheng, L.P.; Jiang, H.T. Analysis of fermentation rule and aromatic composition of olive wine fermented with different species of yeast strains. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2014, 35, 203–208. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.Z.; Fan, J.R.; Peng, J.G.; Yang, H.B.; Yang, B.N.; He, M.B. Analysis of the oil content and its fatty acid composition of fruits for introduced olive cultivars in Sichuan province. Sci. Silv. Sin. 2010, 46, 91–100. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- IOC. World Olive Oil Figures. Available online: http://www.internationaloliveoil.org/estaticos/view/131-world-olive-oil-figures (accessed on 31 July 2017).

- IOC. World Table Olive Figures. Available online: http://www.internationaloliveoil.org/estaticos/view/132-world-table-olive-figures (accessed on 31 July 2017).

- He, Z.M.; Wu, J.C.; Yao, C.Y.; Yu, K.T. Lipase-catalyzed hydrolysis of olive oil in chemically-modified AOT/isooctane reverse micelles in a hollow fiber membrane reactor. Biotechnol. Lett. 2001, 23, 1257–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Finance Net. China Olive Industry Innovation Strategy Alliance Established. Available online: http://finance.china.com.cn/roll/20160827/3879746.shtml (accessed on 25 August 2017). (In Chinese).

- Chiara, R.G.; Laura, D.C.; Francesco, P.F. Tunisian Extra Virgin Olive Oil Traceability in the EEC Market: Tunisian/Italian (Coratina) EVOOs Blend as a Case Study. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekhay, O.; Arriaza, M. How Attractive Is Upland Olive Groves Landscape? Application of the Analytic Hierarchy Process and GIS in Southern Spain. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOC. Olive Growing in China. Available online: https://www.oliveoilmarket.eu/olive-growing-in-china (accessed on 31 March 2018).

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).