Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Social Isolation among North Korean Refugee Women in South Korea: The Moderating Role of Formal and Informal Support

Abstract

1. Introduction

Background: Traumatic Events and PTSD among North Korean Refugee Women

2. Literature Review

2.1. Relationship between PTSD and Social Isolation

2.2. Moderation Effect of Formal and Informal Social Support

2.3. Covariates

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Social Isolation

3.2.2. PTSD

3.2.3. Formal Support

3.2.4. Informal Support

3.2.5. Covariates

3.3. Data Analysis Plan

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Husban, M.; Adams, C. Sustainable Refugee Migration: A Rethink towards a Positive Capability Approach. Sustainability 2016, 8, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachocka, M. The Twin Migration and Refugee Crises in Europe: Examining the OECD’s Contribution to the Debate. In Rocznik Instytutu Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej, 14(4 Re-thinking the OECD’s Role in Global Governance: Members, Policies, Influence); 2016; pp. 71–99. Available online: http://yadda.icm.edu.pl/yadda/element/bwmeta1.element.ekon-element-000171439566 (accessed on 1 October 2016).

- Crush, J.; Tevera, D.S. (Eds.) Zimbabwe’s Exodus: Crisis, Migration, Survival; Southern African Migration Programme; African Books Collective: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bris, P.; Bendito, F. Lessons Learned from the Failed Spanish Refugee System: For the Recovery of Sustainable Public Policies. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1446. [Google Scholar]

- Crush, J. The dark side of democracy: Migration, xenophobia and human rights in South Africa. Int. Migr. 2001, 38, 103–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, M.Y.; Chi, I.; Kim, H.J.; Palinkas, L.A.; Kim, J.Y. Correlates of depressive symptoms among North Korean refugees adapting to South Korean society: The moderating role of perceived discrimination. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 131, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Unification. Statistic for North Korean Refugees in South Korea. Available online: http://www.unikorea.go.kr/unikorea/business/NKDefectorsPolicy/status/lately/ (accessed on 1 March 2018).

- Lee, D.Y. The Task of Establishing the ‘Constitutional Identity’ and the Constitutional Status of North Korean Defectors. Justice 2013, 136, 27–63. [Google Scholar]

- The New York Times. Life in South hard for North Koreans. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2000/04/24/world/life-in-south-hard-for-north-koreans.html (accessed on 24 April 2010).

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittaway, E.; Muli, C.; Shteir, S. ‘I have a voice—Hear me!’ Findings of an Australian Study Examining the Resettlement and Integration Experience of Refugees and Migrants from the Horn of Africa in Australia. Available online: https://refuge.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/refuge/article/view/32084 (accessed on 17 April 2018).

- Jeon, B.H.; Kim, M.D.; Hong, S.C.; Kim, N.R.; Lee, C.I.; Kwak, Y.S.; Park, J.H.; Chung, J.; Chong, H.; Jwa, E.K. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among North Korean defectors living in South Korea for more than one year. Psychiatry Investig. 2009, 6, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, B.H. Between defector and migrant: Identities and strategies of North Koreans in South Korea. Korean Stud. 2008, 32, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynie, M. The Social Determinants of Refugee Mental Health in the Post-Migration Context: A Critical Review. Can. J. Psychiatry 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, M.; Kushner, K.E.; Dennis, C.; Kariwo, M.; Letourneau, N.; Makumbe, K.; Makwarimba, E.; Shizha, E. Social support needs of Sudanese and Zimbabwean refugee new parents in Canada. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2017, 13, 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, R.; Melville, F.; Steel, Z.; Lacherez, P. Trauma, Post-Migration Living Difficulties, and Social Support as Predictors of Psychological Adjustment in Resettled Sudanese Refugees. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2006, 40, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, A.L.; Peterson, C.; Ubelhor, D. War-related trauma and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder among adult Kosovar refugees. J. Trauma. Stress 2002, 15, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sautter, F.J.; Glynn, S.M.; Thompson, K.E.; Franklin, L.; Han, X. A couple-based approach to the reduction of PTSD avoidance symptoms: Preliminary findings. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2009, 35, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoellner, L.A.; Pruitt, L.D.; Farach, F.J.; Jun, J.J. Understanding heterogeneity in PTSD: Fear, dysphoria, and distress. Depress. Anxiety 2014, 31, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sheikh, N.A.M.; Thabet, A.A.M. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder due to War Trauma, Social and Family Support among Adolescent in the Gaza Strip. J. Nursing Health Sci. 2017, 3, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, N.; Anstey, K.J.; Windsor, T.D.; Luszcz, M.A. Disability and depressive symptoms in later life: The stress-buffering role of informal and formal support. Gerontology 2011, 57, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, P.R. The impact of child symptom severity on depressed mood among parents of children with ASD: The mediating role of stress proliferation. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2006, 36, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozbay, F.; Johnson, D.C.; Dimoulas, E.; Morgan, C.A., III; Charney, D.; Southwick, S. Social support and resilience to stress: From neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2007, 4, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- King, D.W.; Taft, C.; King, L.A.; Hammond, C.; Stone, E.R. Directionality of the association between social support and posttraumatic stress disorder: A longitudinal investigation. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 36, 2980–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffaye, C.; Cavella, S.; Drescher, K.; Rosen, C. Relationships among PTSD symptoms, social support, and support source in veterans with chronic PTSD. J. Trauma. Stress 2008, 21, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clapp, J.D.; Beck, J.G. Understanding the relationship between PTSD and social support: The role of negative network orientation. Behav. Res. Ther. 2009, 47, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubos, R. Social Capital: Theory and Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Noh, J.W.; Park, H.; Kwon, Y.D.; Kim, I.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, S.G. Gender Differences in Suicidal Ideation and Related Factors among North Korean Refugees in South Korea. Psychiatry Investig. 2017, 14, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Loon, L.; Van de Ven, M.O.; Van Doesum, K.; Hosman, C.M.; Witteman, C.L. Parentification, stress, and problem behavior of adolescents who have a parent with mental health problems. Fam. Process 2017, 56, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Lim, S.Y.; Jun, J.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Yoo, S.Y.; Kim, S.; Gwak, A.R.; Kim, J.-C.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, S.J. The effect of traumatic experiences and psychiatric symptoms on the life satisfaction of North Korean refugees. Psychopathology 2017, 50, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdonald, D.S. The Koreans: Contemporary Politics and Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cathcart, A.; Korhonen, P. Death and Transfiguration: The Late Kim Jong-il Aesthetic in North Korean Cultural Production. Popul. Music Soc. 2017, 40, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report on Human Rights Abuses or Censorship in North Korea. Available online: https://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/266853.htm (accessed on 11 January 2017).

- Yi, S.H. The Social and Psychological Acculturation of North Korean Refugees; SNU Press: Seoul, Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.J. The Abuses of Human Rights and Identity Change Processes of Women Defectors from North Korea: Focusing on Married Lives of North Korean Women Defectors in North Korea, China, and South Korea. Ph.D. Thesis, Hanyang University, Seoul, Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, B.; Kim, J.Y.; Ryu, W. Intimate partner violence against women among North Korean refugees: A comparison with South Koreans. J. Interpers. Violence 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karunakara, U.K.; Neuner, F.; Schauer, M.; Singh, K.; Hill, K.; Elbert, T.; Burnha, G. Traumatic events and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder amongst Sudanese nationals, refugees and Ugandans in the west Nile. Afr. Health Sci. 2004, 4, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lankov, A. North Korean refugees in Northeast China. Asian Surv. 2004, 44, 856–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Gerber, J. ‘We Just Do What We Think Is Right. We Just Do What We Are Told: ‘Perceptions of Crime and Justice of North Korean Defectors. Asia Pac. J. Police Crim. Justice 2009, 7, 21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, E.; Schloenhardt, A. North Korean refugees and international refugee law. Int. J. Refug. Law 2007, 19, 215–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Lee, M.K.; Chun, K.H.; Lee, Y.K.; Yoon, S.J. Trauma experience of North Korean refugees in China. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001, 20, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Oh, S. The MMPI-2 profile of North Korean female refugees. Korean J. Psychol. Gen. 2010, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.Y.; Choi, J.H.; Ryu, W. Impact of PTSD on North Korean Defector’s Social Adjustment in South Korea; Focused on the Moderating Effect of Resilience and Social Interaction. Korean J. Soc. Welf. Stud. 2012, 43, 343–367. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.; Yoo, S. North Korean Defectors Panel Study (Economic Adaptation, Mental Health Physical Health); North Korean Refugees Foundation: Seoul, Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, E.B.; Rosser-Hogan, R. Trauma experiences, posttraumatic stress, dissociation, and depression in Cambodian refugees. Am. J. Psychiatry 1991, 148, 1548–1551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, S.G.; Litz, B.T.; Weathers, F.W. Social anxiety, depression, and PTSD in Vietnam veterans. J. Anxiety Disord. 2003, 17, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, N. Participatory action research with asylum seekers and refugees experiencing stigma and discrimination: The experience from Scotland. Disabil. Soc. 2014, 29, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoom, M.R. Social isolation of the stateless and the destitute: A study on the refugee-camp and the sullied slum of Dhaka city. Urban Stud. Res. 2016, 2016, 9017279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindert, J.; von Ehrenstein, O.S.; Priebe, S.; Mielck, A.; Brähler, E. Depression and anxiety in labor migrants and refugees–A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heeren, M.; Wittmann, L.; Ehlert, U.; Schnyder, U.; Maier, T.; Müller, J. Psychopathology and resident status–comparing asylum seekers, refugees, illegal migrants, labor migrants, and residents. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 818–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harman, R.; Lee, D. The role of shame and self-critical thinking in the development and maintenance of current threat in post-traumatic stress disorder. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2010, 17, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cloitre, M.; Miranda, R.; Stovall-McClough, K.C.; Han, H. Beyond PTSD: Emotion regulation and interpersonal problems as predictors of functional impairment in survivors of childhood abuse. Behav. Ther. 2005, 36, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehring, T.; Quack, D. Emotion regulation difficulties in trauma survivors: The role of trauma type and PTSD symptom severity. Behav. Ther. 2010, 41, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.H.; Park, E.; Park, J.; Jung, T. Social Adaptation of College Students from North Korea: A Case Study with Focus on Complex-PTSD. Korean J. Stress Res. 2008, 21, 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Thew, G.R.; Gregory, J.D.; Roberts, K.; Rimes, K.A. Self-critical thinking and overgeneralization in depression and eating disorders: An experimental study. Behav. Cognit. Psychother. 2017, 45, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Kolk, B.A. Developmental trauma disorder: Toward a rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories. Psychiatr. Ann. 2017, 35, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Kaczkurkin, A.N.; Mclean, C.P.; Foa, E.B. Emotion Regulation Is Associated With PTSD and Depression among Female Adolescent Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse. Psychol. Trauma. Theory, Res. Pract. Policy 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzeszutek, M.; Oniszczenko, W.; Firląg-Burkacka, E. Social support, stress coping strategies, resilience and posttraumatic growth in a Polish sample of HIV-infected individuals: Results of a 1 year longitudinal study. J. Behav. Med. 2017, 40, 942–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, A.J.; Scarapicchia, T.M.; McDonough, M.H.; Wrosch, C.; Sabiston, C.M. Changes in social support predict emotional well-being in breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 2017, 26, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elzinga, B.M.; Schmahl, C.G.; Vermetten, E.; van Dyck, R.; Bremner, J.D. Higher Cortisol Levels Following Exposure to Traumatic Reminders in Abuse-Related PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003, 28, 1656–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQuaid, R.J.; McInnis, O.A.; Paric, A.; Al-Yawer, F.; Matheson, K.; Anisman, H. Relations between plasma oxytocin and cortisol: The stress buffering role of social support. Neurobiol. Stress 2016, 3, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, B.; Brewin, C.R.; Rose, S. Gender, social support, and PTSD in victims of violent crime. J. Trauma. Stress 2003, 16, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, M.; Anderson, J.; Beiser, M.; Mwakarimba, E.; Neufeld, A.; Simich, L.; Spitzer, D. Multicultural meanings of social support among immigrants and refugees. Int. Migr. 2008, 46, 123–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.R.; Siu, O.L.; Yeh, A.G.O.; Cheng, K.H.C. Informal social support and older persons’ psychological well-being in Hong Kong. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. 2008, 23, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, G.; Minushkin, S.; Cohn, D. Hispanics and Health Care in the United States: Access, Information and Knowledge; Pew Hispanic Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado-de-Mendoza, A.; Gonzales, F.A.; Serrano, A.; Kaltman, S. Social isolation and perceived barriers to establishing social networks among Latina immigrants. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 2014, 53, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, B.A. Examining the relationship between stress and lack of social support in mothers of children with autism. Focus Autism Dev. Disab. 2002, 17, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, S.E.; Filipas, H.H. Correlates of formal and informal support seeking in sexual assault victims. J. Interpers. Violence 2001, 16, 1028–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H. Changes in the North Korean Economy Reported by North Korean Refugees. North Korean Rev. 2008, 4, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, W.T. Issues and problems of adaptation of North Korean defectors to South Korean society: An in-depth interview study with 32 defectors. Yonsei Med. J. 2000, 41, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.C. A study on North Korean Defectors adaptations to local community-focusing on North Korean women. Korean Acad. Qual. Res. Soc. Welf. 2015, 9, 201–225. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Unification. Nationwide Survey about Settlement of North Korean Refugees in South Korea; Kerea Hana Foundation: Seoul, Korea, 2017.

- Ministry of Unification. Nationwide Survey about Social Integration Survey for North Korean Refugees; Kerea Hana Foundation: Seoul, Korea, 2017.

- Sohn, H.M. The Korean Language; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, J.K.; Cho, J.A. Issues in the Integration Education for North Korean Refugees and South Korean Hosts. Korean Psychol. Assoc. 2008, 14, 487–518. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.R.; Ko, Y.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Park, Y.M.; Lee, H.R. School Life of North Korean Defectors Born in the Third Country: Qualitative Case Study. Korean Acad. Soc. Welf. 2017, 39, 205–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.R. The effect of the adjustment stress and the social support on the depressive symptoms of the North Korean defectors. Korean Acad. Soc. Welf. 2005, 57, 193–217. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.; Cho, Y.; Yoon, I.J. Social inclusion and length of stay as determinants of health among North Korean refugees in South Korea. Int. J. Public Health. 2009, 54, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidet, E. Social capital and work integration of migrants: The case of North Korean defectors in South Korea. Asian Perspect. 2009, 33, 151–179. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A.G. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1992, 1, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S. The Relationship among Leisure Sports participation, Social Support, Loneliness and Social Network of the Elderly. Ph.D. Thesis, Myung-Ji Universsity, Seoul, Korea, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, D.; Peplau, L.A.; Fergusson, M.L. Developing a measure of loneliness. J. Personal. Assess. 1978, 42, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, W.T.; Yoon, D.R.; Um, J.S. Survey Results of Adaptation and Life of North Korean Defectors in South Korea, 2001. Korean Unific. Stud. 2003, 7, 155–208. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Choi, B. The Effectiveness of PTSD Program of North Korean Refugees: For North Korean Female Refugees. Korean J. Woman Psychol. 2013, 18, 533–548. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. Y.; Ryu, W. A Study on Cycle of Child Abuse among North Korean Refugee Women: Focused on Aggravating Effects of Spouse Abuse. Korean Fam. Welf. Assoc. 2016, 52, 375–399. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, D.A.; Roberts, W.C. Experiences of violence, perceptions of neighborhood, and psychosocial adjustment among West African refugee youth. Int. Perspect. Psychol. Res. Pract. Consult. 2015, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.L. Desiring Place: Iranian” refugee” women and the cultural politics of self and community in the Diaspora. Comp. Stud. South Asia Afr. Middle East 2000, 20, 180–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, B.A. 3-year follow-up study of psychosocial functioning and general symptoms in settled refugees. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2002, 106, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothbaum, B.O.; Kearns, M.C.; Reiser, M.E.; Davis, M.J.S.; Kerley, M.K.A.; Rothbaum, M.A.O.; Mercer, K.B.; Price, M.; Houry, D.; Ressler, K.J. Early intervention following trauma may mitigate genetic risk for PTSD in civilians: A pilot prospective emergency department study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boateng, A. Survival voices: Social capital and the well-being of Liberian refugee women in Ghana. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2010, 8, 386–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Shin, H.K. In Plans to Enhance the Capability of the Security Police to Prevent Social Deviance of North Korean Defectors, 2013. Korean Assoc. Public Secur. Adm. 2013, 9, 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben, J.R. Sources of social support and burnout: A meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoits, P.A. Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What next? J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Sherman, D.K.; Taylor, S.E. Culture and social support. Am. Psychol. 2008, 63, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crush, J.; Ramachandran, S. Xenophobia, International Migration and Human Development; No. HDRP-2009-47; Human Development Report Office (HDRO), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Revised September 2009. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/hdr/papers/hdrp-2009-47.html (accessed on 1 September 2009).

- Sow, P.; Adaawen, S.A.; Scheffran, J. Migration, social demands and environmental change amongst the Frafra of Northern Ghana and the Biali in Northern Benin. Sustainability 2014, 6, 375–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachocka, M. The European Union and international migration in the early 21st century: Facing the migrant and refugee crisis in Europe. In Re-thinking EU Education on and Research for Smart and Inclusive Growth (EuInteg); PECSA: Warsaw, Poland, 2015; pp. 531–557. Available online: https://depot.ceon.pl/handle/123456789/10269 (accessed on 17 April 2018).

- Castles, S. Development and migration—Migration and development: What comes first? Global perspective and African experiences. Theoria 2009, 56, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffran, J.; Marmer, E.; Sow, P. Migration as a contribution to resilience and innovation in climate adaptation: Social networks and co-development in Northwest Africa. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 33, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N (%) | M (SD) * | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | - | 42.78 (9.23) | 21–77 | |

| Duration in South Korea | - | 6.49 (2.27) | 2–16 | |

| Monthly Income | No income | 7 (4.5) | - | - |

| Under $1000 | 55 (35.7) | - | - | |

| $1000–$1999 | 45 (29.2) | |||

| $2000–$2999 | 29(18.8) | - | - | |

| Over $3000 | 18(11.7) | - | - | |

| Employment & Work difficulties | Single | 36 (23.2) | - | - |

| Married | 118(76.8) | - | - | |

| Language & Culture difficulties | Suicidal ideation | 61 (39.6) | - | |

| Suicidal plan | 48 (31.2) | - | - | |

| Suicidal attempt | 26 (16.9) | - | - | |

| Any suicidal risk | 69 (44.8) | - | - | |

| Social isolation | - | 2.09 (0.39) | - | |

| PTSD | 89 (59.7%) | - | ||

| Formal support | - | 2.56 (0.60) | - | |

| Informal support | - | 2.58 (0.57) | - | |

| Variables | Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | 95% CI | |

| Constant | 1.994 | 0.225 | [1.55, 2.44] | |

| Age | −0.009 | 0.034 | −0.019 | [−0.08, 0.06] |

| Duration in South Korea | 0.097 | 0.050 | 0.148 | [0.00, 0.20] |

| Income | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.032 | [0.00, 0.00] |

| Employment & work difficulties | 0.107 | 0.048 | 0.182 * | [0.01, 0.20] |

| Language & culture difficulties | 0.042 | 0.021 | 0.171 * | [0.00, 0.08] |

| PTSD | 0.199 | 0.050 | 0.296 *** | [0.10, 0.30] |

| Formal support | −0.046 | 0.053 | −0.070 | [−0.15, 0.06] |

| Informal support | −0.187 | 0.057 | −0.277** | [−0.30, −0.07] |

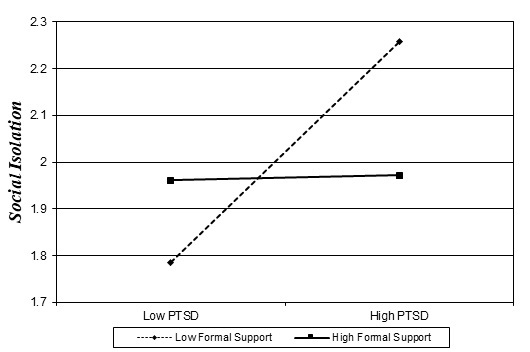

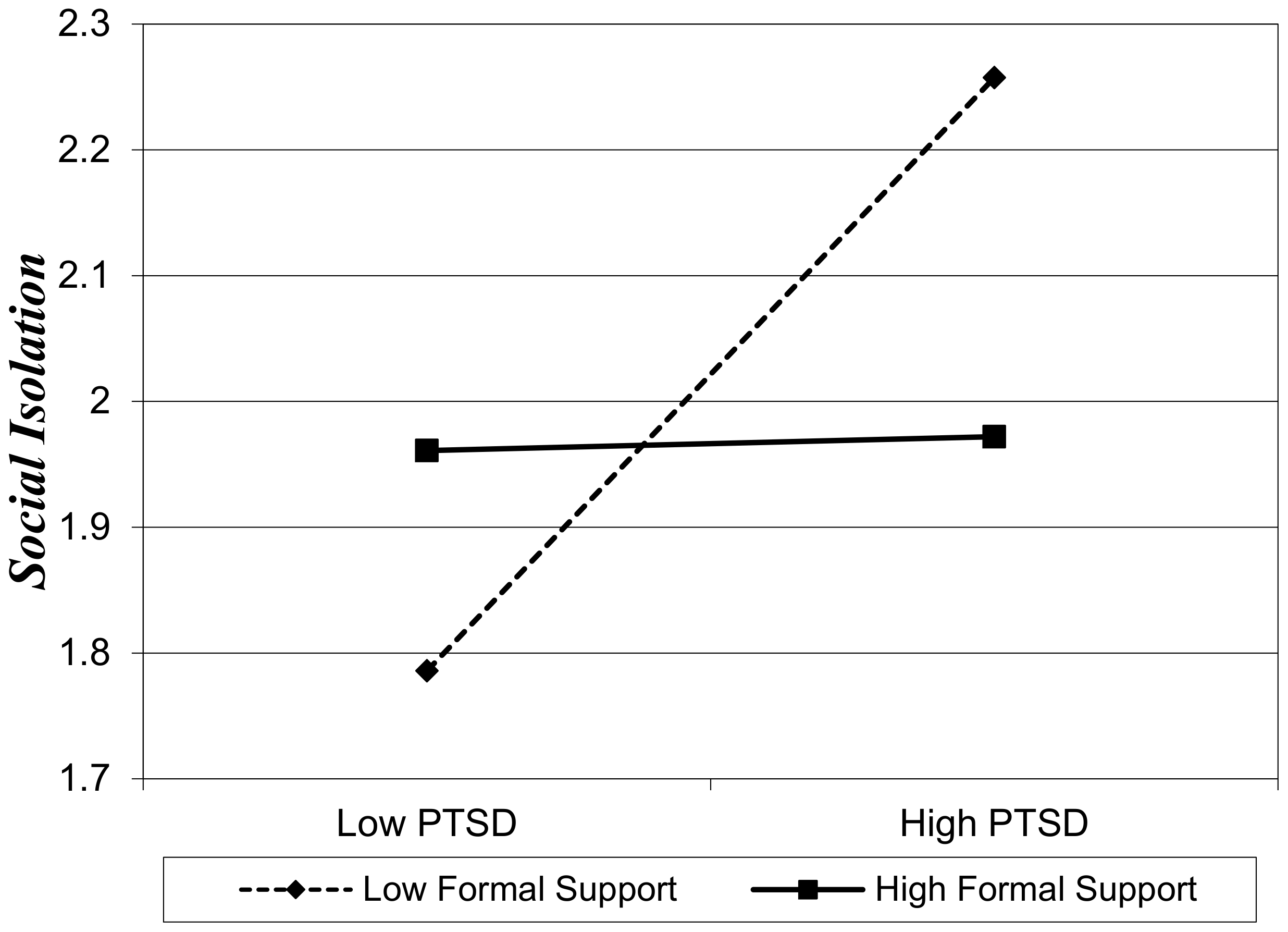

| PTSD X Formal support | −0.317 | 0.097 | −0.258 ** | [−0.51, −0.13] |

| PTSD X Informal support | 0.174 | 0.090 | 0.158 | [0.00, 0.35] |

| R2 | 0.279 | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.286 ** | |||

| F | 6.567 *** | |||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ryu, W.; Park, S.W. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Social Isolation among North Korean Refugee Women in South Korea: The Moderating Role of Formal and Informal Support. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041246

Ryu W, Park SW. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Social Isolation among North Korean Refugee Women in South Korea: The Moderating Role of Formal and Informal Support. Sustainability. 2018; 10(4):1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041246

Chicago/Turabian StyleRyu, Wonjung, and Sun Won Park. 2018. "Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Social Isolation among North Korean Refugee Women in South Korea: The Moderating Role of Formal and Informal Support" Sustainability 10, no. 4: 1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041246

APA StyleRyu, W., & Park, S. W. (2018). Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Social Isolation among North Korean Refugee Women in South Korea: The Moderating Role of Formal and Informal Support. Sustainability, 10(4), 1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041246