The Challenge to Foster Foreign Students’ Experiences for Sustainable Higher Educational Institutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations and Model Development

2.1. The Stakeholder Theory

2.2. Experiential Marketing

2.3. Erasmus Students as a New Target Market for Tourism

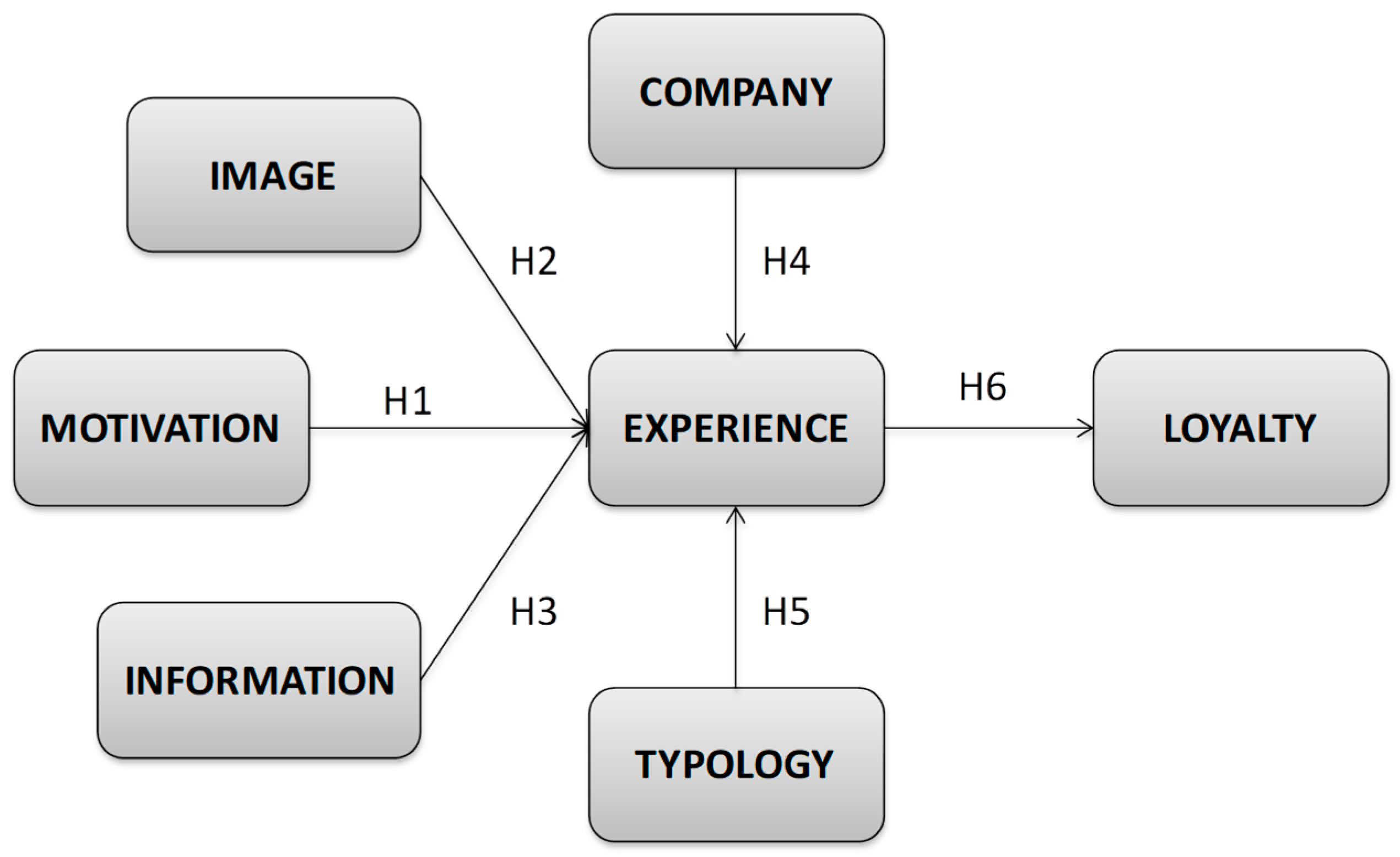

3. Theoretical Model Development

4. Method

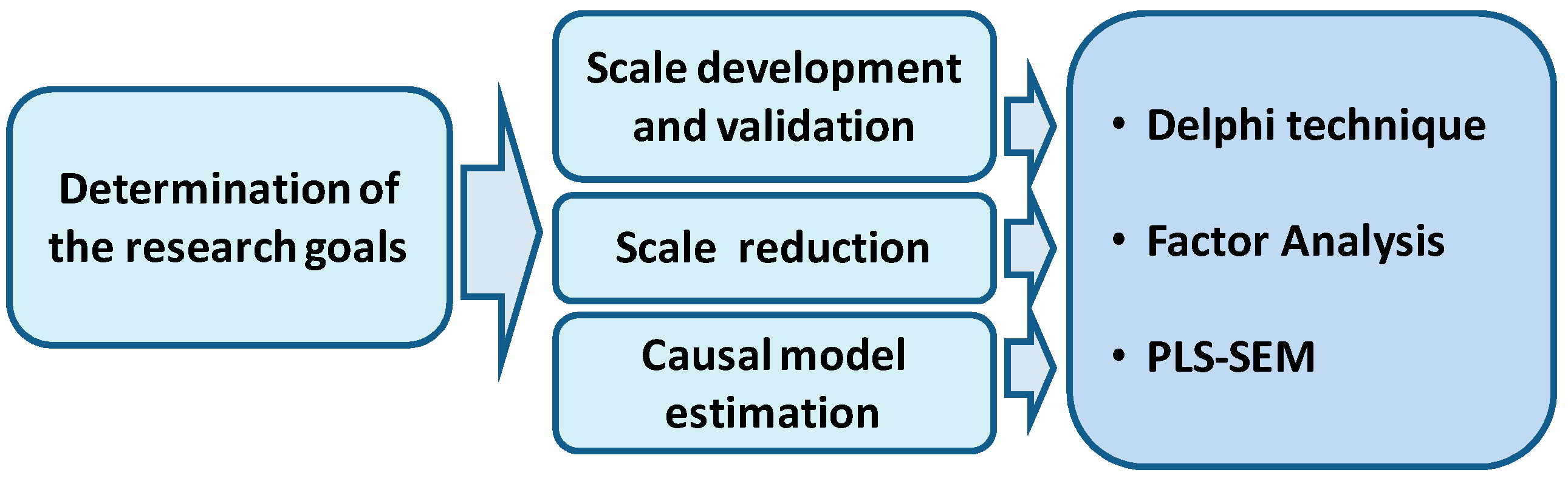

4.1. Techniques

4.2. Sample and Procedure

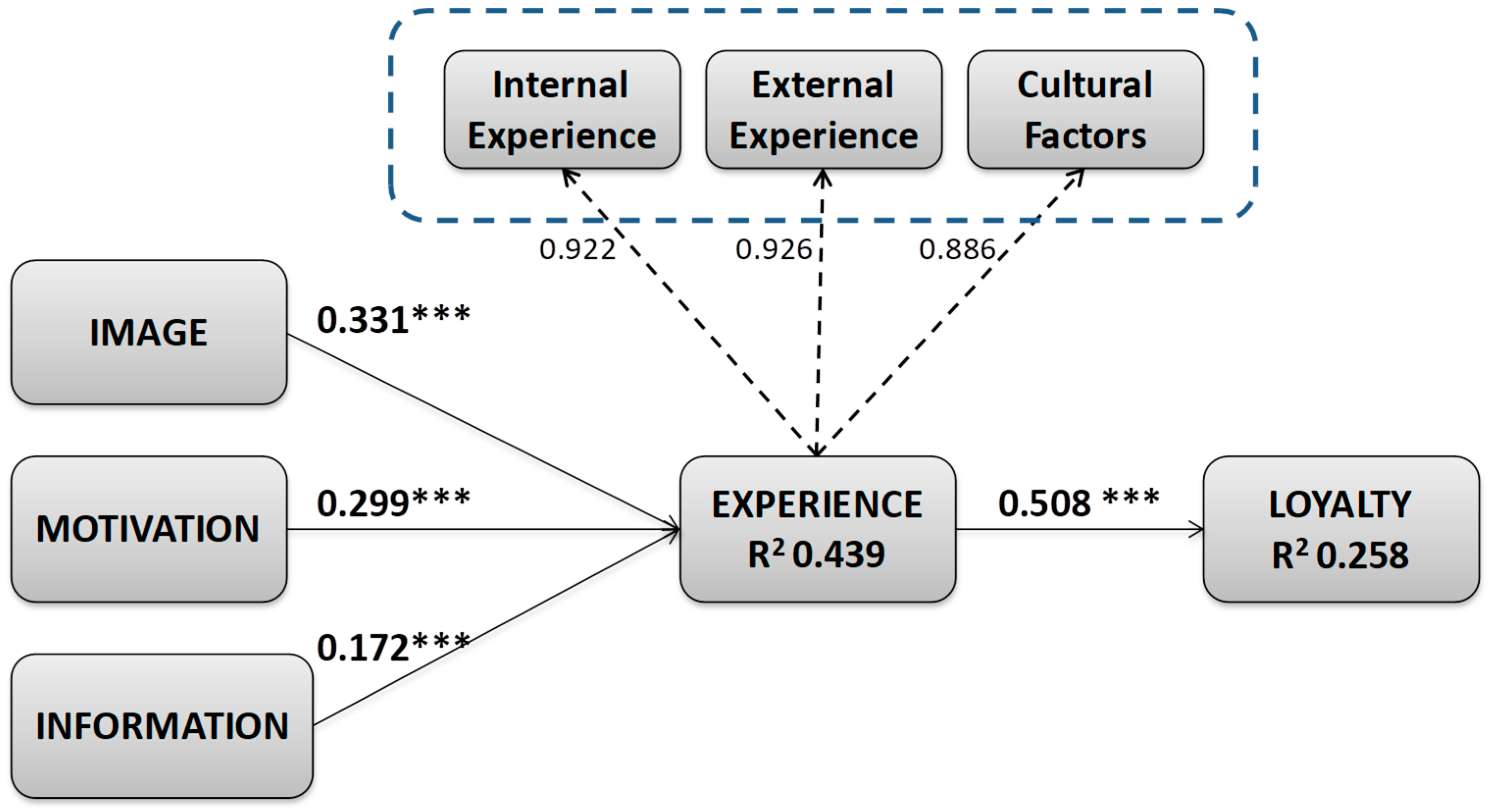

5. Results and Discussion

6. Concluding Remarks

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Scales of Measure

- Budget available (MOT1)

- Events and festivals (MOT2)

- Visiting as much as I can to take profit from my grant (MOT3)

- Visiting with family and friends (MOT4)

- Proximity (IM01)

- Monuments and history (IM02)

- Good reputation (IM03)

- Avoiding routine without spending so much money (IM04)

- Countryside (IM05)

- Beaches (IM06)

- Visiting friends (IM07)

- Cultural activities (IM08)

- Regional festivities and traditions (IM09)

- With other Erasmus students (CQ1)

- With the friends I met at the destination (CQ2)

- I used to travel alone (CQ3)

- Adventure (TP1)

- History and heritage (TP2)

- Sun and beach (TP3)

- Leisure and entertainment (TP4)

- Packages from tourist agencies (INFO1)

- Other Erasmus students’ recommendations (INFO2)

- Packages from Erasmus agencies (INFO3)

- Own plans and timetable (INFO4)

- Packages from tourist agencies for Erasmus students (INFO5)

- Happy to have had a new experience (EXP01)

- To have enjoyed the activities offered by the destination (EXP02)

- To have enjoyed the tourist experience (EXP03)

- Emotions (EXP04)

- Once in a lifetime (EXP05)

- Unique place (EXP06)

- To experience something new (EXP07)

- Good memories from local people (EXP08)

- Local culture experiences (EXP09)

- Friendship with local people (EXP10)

- Freedom experiences (EXP11)

- Refreshing experiences (EXP12)

- Revival experiences (EXP13)

- I did something significant (EXP14)

- I did something important in my life (EXP15)

- I learned about myself (EXP16)

- I visited one place where I have always wanted to go (EXP17)

- I did activities that I have always wanted to do (EXP18)

- I was very interested in all of the activities offered at the destination (EXP19)

- I explored the destination on my own (EXP20)

- I acquired new knowledge (EXP21)

- I knew a new culture (EXP22)

- I will try to come back to this country next year (LOY1)

- I will encourage family and friends to visit the country (LOY2)

- I have enjoyed my time in this country (LOY3)

- I will share my experience with colleagues and social networks (LOY4)

References

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone Publishing Limited: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo-Abondanoa, J.M.; Trujilloa, M.A.; Guzmána, A. Corporate Governance in Higher Education Institutions in Colombia. 2012. Available online: http://aplicaciones2.colombiaaprende.edu.co (accessed on 4 October 2017). (In Spanish).

- Altbach, P.G.; Reisberg, L.; Rumbley, L.E. Trends in Global Higher Education: Tracking an Academic Revolution; Report for the 2009 World Conference on Education, UNESCO; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. Corporate social responsibility education in Europe. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 54, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.J.; Peirce, E.; Hartman, L.P.; Hoffman, W.M.; Carrier, J. Ethics, CSR, and sustainability education in the Financial Times top 50 global business schools: Baseline data and future research directions. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 73, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Mainardes, E.W. University social responsibility: A student base analysis in Brazil. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2016, 13, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeShields, O.W., Jr.; Kara, A.; Kaynak, E. Determinants of business student satisfaction and retention in higher education: Applying Herzberg’s two-factor theory. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2005, 19, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC). Travel & Tourism Economic Impact 2016. Spain. 2016. Available online: www.wttc.org (accessed on 14 February 2017).

- EHEA. European Higher Education Area and Bologna Process. 2017. Official Web Page. Available online: www.ehea.info (accessed on 14 February 2017).

- Rutherford, J. Cultural Studies in the Corporate University. Cult. Stud. 2005, 19, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, R.; Nedeva, M. Employing Discourse: Universities and Graduate Employability. J. Educ. Policy 2010, 25, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, E.; Franco, M. The importance of networks in the transnational mobility of higher education students: Attraction and satisfaction of foreign mobility students at a public university. Stud. High. Educ. 2016, 41, 1627–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, G.; Scholes, K. Exploring Corporate Strategy; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ruf, B.M.; Muralidhar, K.; Brown, R.M.; Janney, J.J.; Paul, K. An empirical investigation of the relationship between change in corporate social performance and financial performance: A stakeholder theory perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 32, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, C. What’s a Business for? Available online: http://faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/brchen/what%20is%20a%20business%20for.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2018).

- Shiller, R.J. The Subprime Solution: How Today’s Global Financial Crisis Happened, and What to Do about It; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B.; Buchholtz, A.K. Business and Society: Ethics, Sustainability, and Stakeholder Management; Cengage Learning: Stamford, CT, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, M.J.; Buhovac, A.R. Making Sustainability Work: Best Practices in Managing and Measuring Corporate Social, Environmental, and Economic Impacts; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultén, B. Sensory marketing: The multi-sensory brand-experience concept. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2011, 23, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leighton, D. Step back in time and live the legend: Experiential marketing and the heritage sector. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2007, 12, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Alant, K. The hedonic nature of wine tourism consumption: An experiential view. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiotsou, R.; Ratten, V. Future research directions in tourism marketing. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2010, 28, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapito, D.; Mendes, J.; Valle, P. Exploring the conceptualization of the sensory dimension of tourist experiences. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilansky, S. Experiential Marketing: A Practical Guide to Interactive Brand Experiences; Kogan Page: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.S.; Hsiao, H.D.; Yang, M.F. The study of the relationships among experiential marketing, service quality, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty. Int. J. Org. Innov. 2011, 3, 352–378. [Google Scholar]

- Carù, A.; Cova, B. Revisiting consumption experience. More humble but complete view of the concept. Mark. Theory 2003, 3, 259–278. [Google Scholar]

- Walls, A.; Okumus, F.; Wang, Y.; Kwun, D. An epistemological view of consumer experiences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Prayag, G.; Deesilatham, S.; Cauševic, S.; Odeh, K. Measuring Tourists’ Emotional Experiences: Further Validation of the Destination Emotion Scale. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.H.E.; Wu, C.K. Relationships among experiential marketing, experiential value, and customer satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2008, 32, 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.R.; Hudson, S. Understanding and meeting the challenges of consumer/tourist experience research. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Ritchie, J.B.; McCormick, B. Development of a scale to measure memorable tourism experiences. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, M.H. Heritage interpretation, place branding and experiential marketing in the destination management of geotourism sites. Transl. Spaces 2015, 4, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMP. Erasmus Mundus Programme. 2017. Available online: http://eacea.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 14 February 2017).

- Teichler, U. Temporary Study Abroad: The life of ERASMUS students. Eur. J. Educ. 2004, 39, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streitwieser, B.; Van Winkle, Z. The Erasmus citizen: Stundents’ conceptions of citizenship identity in the Erasmus mobility programme in Germany. In Internationalisation of Higher Education and Global Mobility; Streitwieser, B., Ed.; Oxford Studies in Comparative Education, Symposium Books: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, C.; Martins, D. Erasmus Intensive Programme Interhealth–Denmark. A story of experiences and feelings. J. Comen. Assoc. 2008, 17, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Aktan, E.; Sari, B.; Kaymak, I. An Inquiry on application process of EU Erasmus Programme & students’ views regarding Erasmus programme of student exchange. Exedra Revista Científica 2010, 1, 239–268. [Google Scholar]

- Moisă, C. Some Aspects Regarding Tourism and Youth’s Mobility. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 14, 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Cvikl, H.; Artič, N. Can mentors of Erasmus student mobility influence the development of future tourism? Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 19, 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Drozdowska, M.; Duda-Seifert, M. Preferences of Erasmus Students Concerning Culinary Tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. Res. 2014, 4, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez González, C.; Bustillo Mesanza, R.; Mariel, P. The determinants of international student mobility flows: An empirical study on the Erasmus programme. High. Educ. 2011, 62, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupnik, S.; Krzaklewska, E. ESNSurvey 2006: Exchange Students’ Rights; ESN AISBL: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tapachai, N.; Waryszak, R. An examination of the role of beneficial image in tourist destination selection. J. Travel Res. 2000, 39, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, H.; Raposo, M. The influence of university image on student behaviour. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2010, 24, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubillo, J.M.; Sánchez, J.; Cervino, J. International students’ decision-making process. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2006, 20, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.; Saura, I. Value dimensions, perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty: An investigation of university students’ travel behaviour. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, D.; Lin, C.H. Why Do First-Time and Repeat Visitors Patronize a Destination? J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papabitsiba, V. Study Abroad and Experiences of Cultural Distance and Proximity: French Erasmus Students. In Languages for Intercultural Communication and Education: Living and Studying Abroad, Research and Practice; Byram, M., Weng, A., Eds.; Multilingual Matters Ltd.: Clevedon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Plog, S. Why destination areas rise and fall in popularity: An update of a Cornell Quarterly classic. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Admin. Q. 2001, 42, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigram, J.J.; Wahab, S. (Eds.) Tourism, Development and Growth: The Challenge of Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lew, A.; McKercher, B. Modeling tourist movements: A local destination analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.Q.; Qu, H. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J.; Brady, M.K.; Hult, G.T.M. Assessing the effects of quality, value and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigne, J.E.; Sanchez, M.I.; Sanchez, J. Tourism image, evaluation variables and after purchase behaviour: Inter-relationship. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, J.F.; Morais, D.B.; Norman, W. An examination of the determinants of entertainment vacationers’ intentions to visit. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.M.; Hsu, M.H.; Lai, H.; Chang, C.M. Re-examining the influence of trust on online repeat purchase intention: The moderating role of habit and its antecedents. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 53, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, C.; Pawlowski, S.D. The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design considerations and applications. Inf. Manag. 2004, 42, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.J.; Jones, S.; Huntley, C.D.; Seddon, C. What are the key elements of cognitive analytic therapy for psychosis? A Delphi study. Psychol. Psychother. 2017, 90, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, B.; Marques, R.; Neto, O. Delphi technique as a consultation method on regulatory impact assessment (RIA)—The Portuguese water sector. Water Policy 2017, 19, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuribayashi, M.; Hayashi, K.; Akaike, S. A proposal of a new foresight platform considering of sustainable development goals. Eur. J. Futures Res. 2018, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, M.I. Using experts’ opinions through Delphi technique. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2007, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.L. Tourism Analysis: A Handbook, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.; Njite, D. Relationship between destination image and tourists’ future behavior: Observations from Jeju island, Korea. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli Palacio, M.; Martín, J. Tourists’ characteristics and the perceived image of tourist destinations: A quantitative analysis—A case study of Lanzarote, Spain. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, W.J.; Wolfe, K.; Hodur, N.; Leistritz, F.L. Tourist word of mouth and revisit intentions to rural tourism destinations: A case of North Dakota, USA. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo Peña, A.; Frías Jamilena, D.; Rodriguez-Molina, M. The perceived value of the rural tourism stay and its effect on rural tourist behaviour. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Prayag, G. Image, satisfaction and loyalty-The case of Cape Town. Anatolia 2008, 19, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgas-Coll, S.; Palau-Saumell, R.; Sánchez-García, J.; Callarisa-Fiol, L.J. Urban destination loyalty drivers and cross-national moderator effects: The case of Barcelona. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1309–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I. Principal Component Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, vii–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, P.B.; Gaskin, J. Partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modeling (SEM) for building and testing behavioral causal theory: When to choose it and how to use it. Prof. Commun. IEEE Trans. 2014, 57, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuberg, L.G. Causality: Models, reasoning, and inference. Book review. Econom. Theory 2003, 19, 675–685. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl, J. Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, F.; Keeney, S. Enhancing rigor in the Delphi technique research. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2011, 78, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streukens, S.; Leroi-Werelds, S. Bootstrapping and PLS-SEM: A step-by-step guide to get more out of your bootstrap results. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technical Data Sheet | |

|---|---|

| Universe | Incoming Students |

| Geographical scope | Region of Extremadura (Spain) |

| Population census | 496 (course 2015–2016) |

| Period under study | March, April, and May 2015 |

| Method of gathering information | Electronic questionnaire reinforced by phone calls |

| Sample | 202 |

| Participation index | 40.72% |

| Maximum error sample | 5.3% |

| Confidence Level | 95% |

| Delphi Method Specifications | |

|---|---|

| Design type | Classical |

| Participants/panelists | 10 experts (five experts from the tourist sector, five experts from Erasmus institutions) |

| Geographical scope | Region of Extremadura (Spain) |

| Rounds | Two rounds |

| Items to validate | Forty in the first round, and 44 in the second round, considering that four items were added by participants |

| Variables | Motivation, Image, Information, Company, Typology, Experience, Loyalty |

| Scale for validation | 0 Strongly disagree; 1 Disagree; 2 Somewhat disagree; 3 Neutral; 4 Somewhat agree; 5 Agree; 6 Strongly agree |

| Items | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXP16 | 0.803 | 0.205 | 0.155 | −0.159 |

| EXP15 | 0.786 | 0.262 | 0.302 | −0.096 |

| EXP13 | 0.727 | 0.326 | 0.281 | 0.025 |

| EXP12 | 0.717 | 0.33 | 0.226 | 0.13 |

| EXP14 | 0.697 | 0.359 | 0.266 | −0.063 |

| EXP11 | 0.664 | 0.331 | 0.192 | 0.004 |

| EXP05 | 0.506 | 0.269 | 0.361 | 0.023 |

| EXP21 | 0.477 | 0.415 | 0.334 | 0.066 |

| EXP20 | 0.475 | 0.194 | 0.352 | 0.007 |

| EXP10 | 0.288 | 0.812 | 0.044 | −0.035 |

| EXP08 | 0.333 | 0.808 | 0.087 | −0.033 |

| EXP09 | 0.362 | 0.718 | 0.157 | −0.054 |

| EXP02 | 0.11 | 0.622 | 0.54 | 0.01 |

| EXP01 | 0.357 | 0.566 | 0.333 | 0.029 |

| EXP07 | 0.423 | 0.523 | 0.427 | −0.025 |

| EXP04 | 0.468 | 0.502 | 0.357 | 0.152 |

| EXP06 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.413 | 0.24 |

| EXP19 | 0.233 | 0.293 | 0.733 | −0.04 |

| EXP18 | 0.42 | 0.052 | 0.73 | −0.08 |

| EXP17 | 0.464 | 0.031 | 0.688 | −0.095 |

| EXP03 | 0.145 | 0.569 | 0.621 | 0.043 |

| EXP22 | −0.063 | −0.026 | −0.075 | 0.954 |

| % of standard deviation | 49.937 | 6.552 | 5.188 | 4.675 |

| Accumulated % | 49.937 | 56.488 | 61.677 | 66.351 |

| Hypotheses Structural Path A → B | Original Path Coefficient (β) | Expected Sign | Mean Sub-Sample Path Coefficient | t-Value (Standard Error) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Motivation → Experience | 0.298 | + | 0.298 | 4.08 *** (0.07) | Confirmed √ |

| H2: Image → Experience | 0.331 | + | 0.334 | 4.92 *** (0.06) | Confirmed √ |

| H3: Information → Experience | 0.172 | + | 0.173 | 2.79 *** (0.06) | Confirmed √ |

| H4: Company → Experience | 0.059 | + | 0.066 | 0.91 (0.06) | X |

| H5: Typology → Experience | 0.122 | + | 0.123 | 1.74 (0.07) | X |

| H6: Experience → Loyalty | 0.508 | + | 0.505 | 8.66 *** (0.05) | Confirmed √ |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bañegil-Palacios, T.M.; Sánchez-Hernández, M.I. The Challenge to Foster Foreign Students’ Experiences for Sustainable Higher Educational Institutions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020495

Bañegil-Palacios TM, Sánchez-Hernández MI. The Challenge to Foster Foreign Students’ Experiences for Sustainable Higher Educational Institutions. Sustainability. 2018; 10(2):495. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020495

Chicago/Turabian StyleBañegil-Palacios, Tomás M., and M. Isabel Sánchez-Hernández. 2018. "The Challenge to Foster Foreign Students’ Experiences for Sustainable Higher Educational Institutions" Sustainability 10, no. 2: 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020495

APA StyleBañegil-Palacios, T. M., & Sánchez-Hernández, M. I. (2018). The Challenge to Foster Foreign Students’ Experiences for Sustainable Higher Educational Institutions. Sustainability, 10(2), 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020495