Abstract

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has become a major part of the foodservice industry due to external forces which encourage enterprises’ responsiveness. In reality, consumers’ social concern influences their attitudes towards foodservice firms’ socially responsible practices and purchase decisions, thereby influencing senior management to react. Considering this issue, this study examines the impact of senior management’s ethical leadership in evaluating operational, commercial, and economic performances along with the mediating role of CSR in the foodservice industry. A conceptual model was formulated and empirically tested based on responses from 196 foodservice franchise firms in South Korea. The results indicated ethical leadership significantly influenced CSR and operational performance, while CSR also had a positive effect on operational and commercial performances. Additionally, operational performance had a significantly positive influence on commercial performance, which subsequently enhanced economic performance. Overall, the findings highlight the role that ethical leadership exhibited by senior management of foodservice franchises influenced initiation of CSR activities, which provide implications for research and industry practice and is outlined.

1. Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is referred to as “the broad array of strategies and operating practices that a company develops in its efforts to deal with and create relationships with its numerous stakeholders and the natural environment” [1] (p. 10). Since its origin, CSR has shifted from community-level activities (e.g., donation to local facilities or communities) to societal level initiatives (e.g., running a business that will not harm the environment or society) [2]. This expansion has been led by ideological thinking that an organization plays a role as a positive force for social change, as well as driven by the return on investment from CSR initiatives [3]. Moreover, CSR activities contribute to a firm’s social legitimacy, and enable appeal to its institutional environment’s socio-cultural norm [4,5]. Accordingly, the flow of sustained support and resources from external and internal stakeholders is ensured by social legitimacy [5], which ultimately enhances social and financial performances [6,7].

Despite the growing volume of research about the business perspectives of CSR, scholars from various business fields, including Strategy, Marketing, and Organizational Behavior have called for more research on internal (i.e., roles of employees or senior management) rather than external components that shape CSR initiatives in the first place [3,8]. Particularly, the role of senior management is central to understand external events [9], as they are largely driven by selective attention and interpretation, as well as the firm’s internal environment that includes management system and structure [10]. Based on the perceptions of specific events, senior management views social issues as opportunities or threats, and develops certain commitments to address such issues [11]. Within the context of a franchise system, senior management plays a more significant role to encourage its franchisor and franchisees to initiate CSR practices than other industries [12], as they are required to comply with the established rules and standards by the franchise contract [13]. In essence, senior management’s operating philosophy motivates its franchise business to fulfill social goals and objectives, and advocates business engagement with a socially-oriented perspective [14]. Thus, it is necessary to assess the relationship between leadership possessed by senior management and organizational practices and/or strategies (e.g., CSR initiatives) [15].

Furthermore, recent literature has also highlighted a need to develop leadership theories with regards to the interrelationship among CSR, ethical leadership, and organizational performance [3,16]. A leadership theory based on ethical perspectives broadens notions about the conventional leader-subordinate relationship to the leader-stakeholder relationship. It is contended that “building and cultivating…ethically sound relations toward different stakeholders is an important responsibility of leaders in an interconnected stakeholder society” [17] (p. 101). Waldman, Siegel, and Javidan considered the inevitable need to bridge the CSR literature and leadership theory, and called for an integration of various leadership dimensions and practices [18]. Ethical leadership style brings socially-oriented changes and initiatives to an organization as a driver of CSR initiatives [19]. Ethical leadership means to “demonstrate integrity and high ethical standards, considerate and fair treatment of employees, and hold employees accountable for ethical conduct” [20] (p. 130). Even though ethical leadership is considered as a driver of organizational effectiveness (e.g., employee performance [21]; psychological empowerment [22]), there is a paucity of research that investigates how ethical leadership influences CSR’s effectiveness to generate desirable organizational outcomes.

Previous studies have conducted the influences of CSR initiatives on stakeholders’ retention, loyalty, task performance, and support [3]. However, little is known about how senior management’s leadership style drives a firm’s CSR initiatives and enhances organizational consequences [3,19]. Given the growing interest in CSR as a global corporate priority, the influence of senior management leadership on CSR practices remains limited and needs further examination [3,19]. Applying the notions to strategic management and ethical leadership, senior management with strong ethical and responsible leadership tend to more likely create a socially responsible organizational culture. Since the perception of CSR is intangible, and may be vague, it needs to be implemented by tangible policies and processes (i.e., CSR activities) to realize its full performance [23].

The purpose of this study is to investigate how ethical leadership adopted by senior management of a firm influences its CSR activities and organizational outcomes. The study is placed within the context of foodservice franchise industry, and examines the perspectives from the franchise country’s headquarters based in Seoul, South Korea. In the Korean franchise industry, the system is generally comprised of a top-down decision-making process, and its structure is highly centralized and formalized with authority concentrated at the senior management level [24]. The top-down structure is typical in South Korean society as there is a power distance and hierarchy, which differs from those in western societies [25]. Hence, an examination will enhance knowledge and practices of a socially oriented food service franchising business in South Korea.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Franchise Industry

Franchise is a business model where a franchisor grants to franchisees a right to distribute, sell, market, as well as produce the franchisor’s services and/or products. To operate a franchise business, the franchisees are in exchange for a fee under permission of the franchisor’s reputation, trademarks, name, and guidance such as techniques and procedures [13]. Franchising businesses are beneficial in the sense that franchisees can easily initiate their business with a small investment along with operational and technical skills learned by franchisors. On the other hand, franchisors can also reach rapid market growth and profitability using franchisees’ capital and labor force [26]. The relationship between a franchisor and franchisee relies heavily on a franchise contract or agreement of two parties so that both should act in the brand’s interest [13,27]. The inter-dependent relationship under the franchise contract mutually benefits two parties (i.e., franchisor and franchisee) to be successful, as well as consider whether CSR activities can enhance performance [27]. Therefore, characteristic of the franchise industry offers a context to explore the influences of CSR activities on organizational performance.

2.2. Ethical Leadership

Although organizations’ ethical behavior has shown rapid growth, there is no consensus on how to best study this phenomenon [28,29]. While ethical leadership has been a focal point, the concept still suffers from disintegration and confusion [28]. The research literature has attempted responses from a combination of empirical and philosophical standpoints [30], or prescriptive, philosophical perspectives [31]. However, “What exactly is ethical leadership?” has yet to be clearly defined [32].

In management studies, ethical leadership is defined as “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making” [20] (p. 120). Based on the approach, a construct of ethical leadership built on a 10-item “Ethical Leadership Scale (ELS)” has been advanced by Brown et al. [20]. The construct embraces the dimension of a leader as moral managers (i.e., who discuss ethical norms or standards with subordinates and offer proper punishments and rewards with regards to ethical/unethical behaviors), and a moral person (i.e., a caring, honest, and principled individual who makes balanced decisions) [20]. In addition, the construct includes critical aspects of other leadership components, such as integrity [33]. However, a moral-manager’s focus of ethical leadership differentiates it from other styles via its transactional nature [28].

On the basis of a social learning perspective, it has been argued that a leader influences the ethical conduct of subordinates through modelling [34]. Such modelling embraces a wide range of “psychological matching processes” [20] (p. 119) that encompasses observational imitation, learning, and identification. The social learning perspective proposes that anyone who can learn from a direct experience can also learn indirectly via observing the behaviors of others and their consequences [35]. In an organizational context, employees can learn via attention to their leader and emulate their values, attitudes, and behaviors [36]. Hence, ethical leaders can be more of a source of guidance and role model due to style and position. Moreover, employees can be taught about expected behaviors, and rewarded via role modelling. Therefore, a leader is of importance and a likely source of modelling by virtue of assigned status, role, success, and possessed power to influence and enforce behaviors and consequences, respectively [36]. The status and power of a leader can also enhance appeal, which makes subordinates pay more attention to the ethical leader’s modeled behaviors [36].

2.3. Corporate Social Responsibility

CSR has been conceptualized as the notion that corporations need to indirectly and directly contribute to the social welfare of a community and society through engagement in activities [37,38,39]. Although scholars have emphasized a corporate’s economic interest and activity, which benefits social goods over the past three decades (e.g., produce a product for community and consumers, whereas being profitable for the business and its stakeholders) [40], several diverse aspects of CSR have emerged [41,42,43]. For example, Carroll [44,45] conceptualizes CSR as a multi-dimensional construct model [43]. The pyramid model embraces four responsibilities: “economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic.” This model considers economic responsibility as the most fundamental aspect of CSR initiatives, and a firm pursues the highest level of CSR aspect with advancement towards philanthropic CSR [44,45].

Based on the multifaceted CSR model, the concept of economic responsibility relates to a firm’s engagement to maximize benefits for the business and its shareholders [46]. Moreover, a firm’s legal responsibility is associated with engagement in a code of ethics or fair rules that “embody moral standards, norms or expectations that reflect a concern for what stockholders view as fair or just” [45] (p. 41). Legal responsibility is based on the principles of utilitarianism and justice [45]. Basically, ethical responsibility is related to a firm’s involvement in social morality at a level that exceeds legal responsibility. As the highest order of CSR initiatives, philanthropic responsibility can be voluntary and demonstrate ideal corporate citizenship. Although the environmental dimension of CSR was not included in Carroll’s CSR model, it needs to be considered. Environmental responsibility refers to a firm’s voluntary activities that demonstrate the inclusion of environmental concerns in interactions with various stakeholders (e.g., non-profit organization, government, consumer, etc.) and in business operations [42]. The multi-dimensional CSR model is a beneficial tool as it embraces the different aspects and levels of activities, and provides a comprehensive assessment of initiatives [45]. The model has also been employed to investigate CSR issues in the restaurant industry [43,47,48], while research has not assessed the direct effect on performance of food service franchises, despite the significant influence reported in various contexts [43].

2.4. Organizational Performance

Previous research has used financial, economic, stock market measures, or rate of market share measures to investigate marketing strategies’ influence on organizational performance [49]. However, several empirical studies as well as theoretical models have indicated that effective economic performance can be achieved with improvement of two separate aspects of organizational performance—operational (i.e., production stage-oriented) and commercial performance (i.e., market stage-oriented) [50,51].

At the first level of product management, operational performance is considered as a major indicator that incorporate components associated with the improvement of efficiency in procedures (e.g., a firm’s innovation capacity, procedures’ flexibility and time, and product quality [49,52]). Thus, the operational performance construct reflects the effectiveness of the operation systems and production with regards to quality, speed, flexibility, costs, etc. [50]. At the second level, organizational performance needs to embrace other indicators, such as firm’s capacity to manage and improve its connections to suppliers, customers, local community, and society [53]. Therefore, a firm’s commercial performance is defined as its commercial function’s effectiveness. It reflects the firm’s ability to meet clients’ demands, and align its behavior and commercial offers with societal values in consideration [54]. Ultimately, the financial and economic performance is a reflection of all the monetary consequences of a firm’s economic activities. As the most traditionally used variable, economic performance reflects measures based on a firm’s profit after tax, economic consequences, sales growth, or market share [55]. This study proposes that a firm’s CSR initiatives may have significant positive results for its procedures that contribute to the enhancement of operational efficiency (i.e., operational performance). This results in improvement of relationships with stakeholders via establishment of responsible attitudes toward society and the environment (i.e., commercial performance). Finally, the operational and commercial performances can improve firm’s economic benefits [49].

Prior research has mainly employed financial performance measures as a consequence of a firm’s socially-oriented activities, which has led to inconsistent results [49]. Hence, more empirical evidence on the interrelationships among the multi-dimensions of organizational performance is needed [55]. Additionally, there is lack of literature with respect to the influence of CSR on product and market-oriented performance, and subsequent implications to adopt initiatives [56]. Consequently, division of organizational performance as independent dimensions can be more effective to examine the hierarchical influences of CSR on organizational performance.

2.5. Research Hypothesis Development

Within an organization, a leader focuses attention on ethical codes via frequent communications about the ethical and social aspects of the firm’s business activities [57]. In accordance with the ethical aspects of leadership, senior management may establish clear and relevant societal responsibilities (e.g., CSR activities), and encourage employees to initiate them [58]. Thus, this study assumes that ethical leadership can be a driver of CSR activities based on social learning. The following hypothesis is formulated:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Ethical leadership is positively associated with CSR.

A leaders’ strategic choice, which is based on their personalities, values, and experiences influences a firm’s performance [23]. Essentially, leaders’ ethical attributes greatly affect their strategic choices and decisions [23,59]. Thus, a firm and its performances can be seen as reflections of ethical characteristics embodied by the leader [60]. Empirical research based on this notion indicates that leaders’ ethical leadership has been significantly associated with organizational performance and in different organizational life cycles [61]. Accordingly, the following hypotheses is outlined:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Ethical leadership is positively associated with operational performance.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Ethical leadership is positively associated with commercial performance.

Several empirical studies have examined the impact of CSR on firm performance with a wide range of positive consequences over the past three decades [62,63]. The fundamental notion is that CSR enhances performance with the improvement of relationships with other stakeholders, which affects expenses and revenues [63]. From a revenue perspective (or commercial standpoint), an enhanced stakeholder relationship attracts new investment opportunities and customers that enables a firm to charge a premium price [64]. From a cost perspective (or operational standpoint) via enhanced relationship, trust leads to decrease in certain processes and transaction costs. CSR activities enhance financial performance and can induce consumers to purchase products and services [63]. More specifically, targeting socially-oriented consumers enables firms to maximize their profits as CSR activities may directly affect satisfaction and loyalty [65]. Therefore, CSR initiatives are advantageous to operational, commercial, and economic performances. The following hypotheses are noted:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

CSR is positively associated with operational performance.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

CSR is positively associated with commercial performance.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

CSR is positively associated with economic performance.

Prior literature has investigated CSR initiatives’ organizational outcomes, corporate image, corporate reputation, and core competences [66]. This study is based on a multidimensional approach of a firm’s performance which proposes that CSR activities may have significant positive outcomes and contribute to increase in operational efficiency. A firm may also enhance its relationship with stakeholders with the adoption of socially responsible behaviors. Such operational and commercial performances may allow a firm to enhance its economic consequences. To measure organizational performance, Hubbard [67] suggests a hierarchical organizational performance model to link the micro to the macro components of organizational performance (i.e., operational activities to market performance). According to Hubbard [67], business activities that embrace social, economic, and environmental perspectives will influence different levels and direction of a firm’s performance since they affect each operation differently due to their complexity. Hence, as demonstrated by Fraj-Andrés et al. [49], this study also seeks to identify the dimensions of organizational performance derived from applying CSR initiatives that benefit firms. The following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Operational performance is positively associated with commercial performance.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Operational performance is positively associated with economic performance.

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

Commercial performance is positively associated with economic performance.

Under strong ethical leadership, a firm is more likely to engage in CSR practices since leaders not only implement CSR activities with determination and consistency, but also support initiatives with solid actions, which in turn enhances the firm’s performance over time [68]. Since CSR is not a short-term engagement project, hence it needs to be formed from strong ethical leadership. In practice, ethical leaders will invest and implement more in CSR initiatives which can positively affect a firm’s performance [69]. However, if a leader with strong ethical leadership does not engage in CSR activities, his/her leadership style cannot directly enhance firm performance [68]. Based on the notion, ethical leadership will indirectly influence firm performance through CSR activities. Hence, the following hypothesis is formulated:

Hypothesis 10 (H10).

CSR mediates the influence of ethical leadership on organizational performance.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

The unit of analysis consisted of international and domestic foodservice franchising firms’ country level headquarters (e.g., Olive Garden, Dunkin Donuts, Lotteria, Pizza Hut, etc.) in South Korea. Since the foodservice industry account for 72.4% of the Korean franchise industry [70], this study only focused on foodservice franchise firms. Firms were selected from the 2015 Korean Franchise General Control registry released by the Korea Fair Trade Commission. Only foodservice franchising firms that had implemented CSR practices (e.g., support fair trade practices; support the welfare of communities) were selected. A total of 418 were compiled, and the lead author contacted representatives at each firm. The objectives of the study were explained to each contact, and upon approval were subsequently requested to distribute the questionnaire (i.e., translated from English to Korean by three bilingual professionals) to their middle-level managers at their headquarters. All completed questionnaires were collected after two weeks during October 2015. Following removal of several responses due to missing information, a final sample of 196 respondents was achieved with a response rate of 46.9 percent.

The rationale to focus on middle-level management is due to the fact that they are immersed in the operational aspects of business practices, and are also most suited to evaluate senior leadership and organizational performance. Additionally, middle-level managers are usually requested to complete various questionnaires as representatives of their respective companies [71]. In the questionnaire, each manager was requested to evaluate their senior management’s ethical leadership style as they are considered to be the primary source to develop and initiate strategies or activities [72]. In addition, participants were asked to assess the business’s performance based on its internal and external reports in terms of finances and CSR.

3.2. Operationalization of Variables

Each construct was measured with multiple items adapted from the literature. All items except for organization’s performance were measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale anchored by “strongly disagree” and “strongly agree.” The ethical leadership construct was measured with ten items [20]. The CSR construct comprised of twenty-three items [38] to measure economic (7 items), legal (6 items), ethical (6 items), and philanthropic (4 items). More specifically, the economic CSR dimension was operationalized as indicate how a franchise company perceived its economic performance. The legal CSR dimension was related to a franchise company’s perception of compliance with law and legal standards. The ethical CSR dimension was emphasized as franchise company’s perception of its ethical behavior. The philanthropic CSR dimension addressed a franchise company’s behavior as well as its interest in philanthropic activities. Finally, organization’s performance was measured on a 7-point Likert scale anchored by “with respect to our competitors, our position is much worse” and “with respect to our competitors, our position is much better”—operational (5 items), commercial (6 items), and economic (5 items) [49]. Additionally, operational performance focuses on the overall improvement of efficiency of processes, while commercial performance is associated with the commercial function’s effectiveness. Economic performance refers to monetary consequences from its economic activities.

4. Results

4.1. Profile of Respondents

Males accounted for 90.3 percent of the respondents while females were 9.7 percent. This skewed result was reflective of the Korean business climate whereby females accounted for only 9 percent of top management position in 2016 [73]. Also, 51.0 percent of the respondents were in their 40 s, and 27.6 percent noted as 30 s, followed by 50 years and above (20.4 percent). Furthermore, 73.5 percent of the respondents were 2- or 4-year college degree holders; 21.4 percent had a graduate degree, and 5.1 percent had a high school diploma. The franchise headquarters varied in size (i.e., numbers of employees), and largely included between 21–40 (33.7 percent) and 41–80 (28.6 percent).

4.2. Data Analysis

In order to assess the unidimensionality of each construct, both confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for CSR dimensions and CFA for all measures were performed using AMOS 20.0. As demonstrated by Lee, Park, and Lee [74], this study operationalized CSR as a latent second order factor composed of four dimensions: economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic activities. First, CFA was conducted to initially identify the dimensions of CSR. Several items were dropped to maintain the level of convergent validity (e.g., standardized factor loadings were lower than 0.5 [75]). All standardized factor loadings were greater than 0.6 (p < 0.01) that provided evidence of convergent validity after the purification procedure (see Table 1). The CFA results suggest the data fit the model: (χ2 = 214.310, d.f. = 84, χ2/d.f. = 2.551, p < 0.001, NFI = 0.905, IFI = 0.940, TLI = 0.925, CFI = 0.940, RMSEA = 0.089).

Table 1.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for corporate social responsibility (CSR) dimensions.

Second, CFA for the measurement model was performed to assess the validity of measures and overall measurement quality. Eight items were dropped to maintain the level of discriminant and convergent validity [75]. After the purification procedure, all standardized factor loadings were greater than 0.6 (p < 0.01) that provided evidence of convergent validity (see Table 2). CFA results suggest the data fit the model: (χ2 = 549.637, d.f. = 199, χ2/d.f. = 2.762, p < 0.001, NFI = 0.906, IFI = 0.924, TLI = 0.911, CFI = 0.923, RMSEA = 0.085).

Table 2.

Results of CFA for measurement model.

Two measures, Composite Construct Reliability (CCR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE), were examined to assess reliability as well as discriminant and convergent validity of the latent constructs. The CCR coefficients all exceeded 0.7 which are noted as the minimum requirement. Also, each AVE estimate exceeded its corresponding interfactor squared correlations [76] which indicates an acceptable level of discriminant validity between any two latent variables (see Table 3). Therefore, the measurement models for ethical leadership, CSR, operational performance, commercial performance, and economic performance constructs were justified in the structural model.

Table 3.

Construct intercorrelations (Φ), mean, standard deviation (SD), Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Composite Construct Reliability (CCR).

Lastly, common method bias was tested via Harman’s one-factor test [38]. A one-factor solution suggests χ2 = 1,767.235 and d.f. = 209 compared with χ2 = 549.637 and d.f. = 199 for the five-factor model. Since the five-factor model had a better fit, common method bias was not a consideration.

4.3. Testing Hypothesized Structural Models

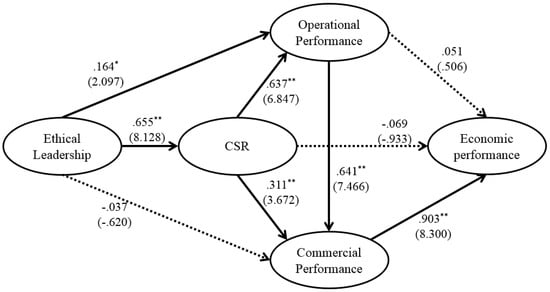

The proposed model was analyzed via structural equation modeling to infer causality between variables [75], and the data fit the model quite well (see Figure 1): χ2 = 549.637, d.f. = 199 (χ2/d.f. = 2.762), p < 0.001, NFI = 0.908, IFI = 0.923, TLI = 0.910, CFI = 0.922, RMSEA = 0.085. The variance explained by the structural relationship was 42.9 percent for CSR, 57.0 percent for operational performance, 76.2 percent for commercial performance, and 80.1 percent for economic performance.

Figure 1.

Estimates of structural equation modeling. Standardized coefficient (t-value), solid line: significant path, dotted line: non-significant path, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

H1 to H3 posit that ethical leadership influences CSR, operational performance, and commercial performance. The results suggest that ethical leadership significantly and positively influenced CSR (coefficient = 0.655, p < 0.01) and operational performance (coefficient = 0.164, p < 0.05), but did not significantly affect commercial performance (coefficient = −0.037, n.s.). Therefore, the results supported H1 and H2, but not H3.

H4 to H6 postulate that CSR influences operational, commercial, and economic performances. Results showed that CSR significantly and positively influenced operational performance (coefficient = 0.637, p < 0.01) and commercial performance (coefficient = 0.311, p < 0.01). These results support H4 and H5. However, CSR did not significantly affect economic performance (coefficient = −0.069, n.s.), and was not supportive of H6.

As hypothesized, operational performance had a significant influence on commercial performance (coefficient = 0.641, p < 0.01), and commercial performance also significantly influenced economic performance (coefficient = 0.903, p < 0.01), thus established support for H7 and H9. Finally, the impact of operational performance on economic performance was not statistically significant (coefficient = 0.051, n.s.), and hence H9 was not supported (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Standardized structural estimates.

4.5. Mediation Test

A Sobel test was conducted to rigorously investigate the mediating roles of CSR, operational, and commercial performances between ethical leadership and economic performance (H10) [77]. In addition, the indirect effects of ethical leadership and CSR on performances were analyzed through the bootstrapping method of AMOS 20.0 with Bootstrap ML and Monte Carlo (95% bootstrap CIs). Findings showed ethical leadership had a significant indirect influence on operational performance through CSR (coefficient = 0.547, p < 0.01) (see Table 5). Also, ethical leadership had a significant direct influence on operational performance (coefficient = 0.164, p < 0.05). Therefore, CSR was regarded as a partial mediator in the relationship between ethical leadership and operational performance (Z-value = 5.210, p < 0.01).

Table 5.

Mediation test.

In addition, CSR had a significant indirect impact on commercial performance through operational performance (coefficient = 0.408, p < 0.01). CSR also had a significant direct impact on commercial performance (coefficient = 0.311, p < 0.01). Thus, operational performance was considered as a partial mediator in the relationship between CSR and commercial performance (Z-value = 5.018, p < 0.01). Meanwhile, CSR had a significant indirect influence on economic performance through commercial performance (coefficient = 0.682, p < 0.01). CSR did not have a significant direct effect on economic performance. Hence, commercial performance was regarded as a full mediator in the relationship between CSR and economic performance (Z-value = 3.331, p < 0.01). Finally, operational performance had a significant indirect influence on economic performance through commercial performance (coefficient = 0.579, p < 0.01). Operational performance did not have a significant direct effect on economic performance. Thus, commercial performance was considered a full mediator in the relationship between operational performance and economic performance (Z-value = 5.510, p < 0.01).

5. Discussion

This study advances knowledge about how each firm’s performance can be enhanced by its ethical leadership style and CSR activities. While the existing literature has investigated antecedents and consequences of CSR; however, empirical studies on the ethical leadership-CSR-firm outcome link is lacking [3,78]. This study provides new findings with the role of CSR as a core mediator in the relationship between senior management’s ethical leadership and the three dimensions of performance in the context of Korean foodservice franchise industry. Such findings have utility in application as the culture of giving is considered to be the most effective approach for a business in South Korea [79].

The focus on senior management is important given their role and influence on the initiation of CSR activities and subsequent organization’s performance. Senior management cognitions and behaviors (i.e., top management leadership) are essential to establish and initiate strategy and/or policy [23]. Hence, this study extends the current literature as the link between ethical leadership, CSR and organizational outcomes were examined. The findings indicated that ethical leadership-based CSR activities seem to be beneficial to enhance each step of organizational outcomes. To generate greater understanding of the consequences of CSR, it was illustrated to divide the organizational outcomes into three independent performances (i.e., operational, commercial, and economical performance).

Within the hospitality and tourism literature and industry applications, CSR has recently become one of the most important topics [43], and the ability to apply such findings may be significant to establish and maintain long-term competitiveness of enterprises [38]. The foodservice industry, in particular, needs to be actively involved in social issues, such as in public health, food wastes, etc. [43]. Consumers expect foodservice enterprises to operate responsibly, and look for detailed information on food preparation, production, and leftovers they consume as well as influences on health of consumers, society, and environment [80]. Thus, foodservice enterprises need to design operations to generate positive influences for society that impact multiple stakeholders [38]. Through CSR initiatives, foodservice enterprises can manage their positive image in society, and generate more trust and brand appeal especially among socially-conscious stakeholders [81]. Consequently, foodservice enterprises with a positive social image can attract new franchisees, suppliers, investors, and customers and be competitive. Therefore, foodservice enterprises need to recognize that they have a social responsibility with regards to the natural environment, consumers, and society [81], which leads them to achieve success through enhancement of performances.

This study demonstrates that ethical leadership of senior management at the franchisor level can, through its CSR activities lead to high levels of economic performance, including operational and commercial performances within the franchise system. The enhancement of senior management’s ethical leadership can be an avenue to initiate additional CSR activities to meet increased societal and consumer demands [82]. Thus, senior management at franchisors need to: (1) focus on the tangible and formal aspects of their ethical infrastructure; (2) build up a code of ethics, a well-designed training on ethics centered leadership for top management, and incentive policies of promoting ethical conduct [83] (p. 290). In essence, senior management needs to firmly establish and sustain, as well as communicate ethical control systems to employees at their headquarters and franchisees to optimally support CSR activities.

The findings also address that it is valuable for foodservice franchise firms to establish and initiate CSR practices to increase operational and commercial performance, which in turn enhances economic performance. Foodservice franchise firms tend to be perceived as being negatively impactful to the natural environment as they generate excessive waste and use non-recyclable packaging materials for delivery services or take-out [84]. Franchisors should review social and environmental policies and practices from various stakeholder perspectives, including society, franchisees, and government [38]. Additionally, they should also assess their level of philanthropic activity, which can make a real difference from competitors, and lead towards profitability.

This study empirically indicated that foodservice franchise companies’ operational and commercial performances are enhanced when they are perceived as socially responsible. Despite the common belief that CSR is essential to a firm’s abilities to meet its stakeholder obligations as well as sustain growth [85], several companies struggle to implement CSR initiatives and enhance business and social returns [66]. However, this study proposes that ethical leadership plays a critical role to promote CSR policies and increase operational performance. To be specific, the ethical leadership style of senior management at foodservice franchise firms may be best suited to initiate, design, implement, and derive CSR practices, which enhances operational performance [3]. Thus, the ethical leadership style of senior management needs to serve to reinforce foodservice franchises’ CSR endeavors.

The results showed that CSR activities positively affected operational and commercial performance while ethical leadership only influenced operational performance. The improvement in commercial performance from operational performance led to better economic outcomes [49]. This study showed that foodservice franchise firms indicated their relative position in terms of separate performance indicators. CSR activities such as, improve the quality of products, comply with all policies and laws that regulate employee benefits and recruitment, establish a comprehensive code of conduct, and contribute toward local community enhancement may enable foodservice franchise companies to reduce costs, while simultaneously improve the product quality, innovative capacity, and pace of a new product launch [43]. However, empirical findings demonstrated that operational performance did not significantly enhance economic performance directly. CSR activities can increase the operational performance of a firm, but this cannot be translated into higher profitability due to several CSR activities that may be a challenge to offset at least in the short period [50]. Nevertheless, the commercial performance was enhanced by CSR activities and the operational performance positively influenced the economic performance. The effect of CSR activities may not be direct, but they are indirect through commercial performance. Thus, simply initiating CSR activities may be not enough to enhance the economic performance as the commercial performance relates to the perceived values of customers, communities, and other involved stakeholders [38]. Accordingly, foodservice franchise companies may need to provide CSR activities with external visibility if these activities need to be valued in the marketplace. Therefore, initiatives need to be implemented by social transformation in the commercial and operational structures, which can improve its competitive position.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the role of ethical leadership of senior management and respective influence on their foodservice franchises’ CSR initiatives along with desirable organizational outcomes. Results identified that CSR significantly mediated the link between the ethical leadership and performances of foodservice enterprises. Further, the findings demonstrated that operational performance had an indirect effect on economic performance through commercial performance, whereas commercial performance had a direct influence on economic performance. Overall, the findings highlight the role that ethical leadership exhibited by foodservice franchise senior management influenced initiation of CSR activities, which provides critical implications for research and industry practice.

7. Limitations and Recommendations

Although our research model demonstrably explains the variance performance, there are additional opportunities for further development. First, other potential factors may change the relative impacts of senior management’s ethical leadership on CSR, such as firm size, structure, and culture. Future research needs to consider controlling for these variables. Second, this study employed self-reported subjective measures to operationalize the three dimensions of performance (e.g., operational, commercial, and economic). Future research could use objective measures such as data in relation to production cost, market share, and total revenues. In addition, this study is based on the four dimensions of CSR established by Carroll [44,45]; however, it does not reflect the environmental perspective, which has been viewed as critical activities. Also, while this study analyzed differences in the domestic and international foodservice franchising firms via independent t-test, there was no significant differences between the firms (i.e., ethical leadership, CSR, and performance). Future research could examine differences between domestic and international firms via multi-group analyses with other drivers of organizational performance. Lastly, data were collected in the context of the South Korean foodservice franchise industry, which is a limitation to the generalizability of the findings. It would add value if future research explored a diverse context and countries for comparative purposes as well as generalities of findings.

Acknowledgments

Publication of this article was funded by the University of Florida Open Access Publishing Fund.

Author Contributions

All authors conceived and designed the research. Min-Seong Kim analyzed the data; Min-Seong Kim wrote Section 1, Section 2, Section 3, Section 4, Section 5, Section 6 and Section 7 and revised the manuscript. Brijesh Thapa wrote Section 1, Section 2, Section 3, Section 4, Section 5, Section 6 and Section 7 and revised the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Waddock, S. Parallel universes: Companies, academics, and the progress of corporate citizenship. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2004, 109, 5–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Corporate social responsibility and competitive advantage: Overcoming the trust barrier. Manag. Sci. 2011, 57, 1528–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Swaen, V.; Lindgreen, A.; Sen, S. The roles of leadership styles in corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Garay, L.; Jones, S. Sustainability motivations and practices in small tourism enterprises in European protected areas. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, G.; Scherer, A. Corporate legitimacy as deliberation: A communicative framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 66, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, L.; Font, X. doing good to do well? Corporate responsibility reasons, practices and impacts in small and medium accommodation enterprises. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.D.; Walsh, J.P. Misery loves companies: Rethinking social initiatives by business. Admin. Sci. Q. 2003, 48, 268–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.J.; Bazerman, M.H. Changing practice on sustainability: Understanding and overcoming the organizational and psychological barriers to action. In Organizations and the Sustainability Mosaic. Crafting Long-Term Ecological and Societal Solutions; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 84–105. [Google Scholar]

- Daft, R.L.; Weick, K.E. Toward a model of organizations as interpretation systems. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 284–295. [Google Scholar]

- Child, J. Strategic choice in the analysis of action, structure, organizations and environment: Retrospect and prospect. Organ. Stud. 1997, 18, 43–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. Managerial interpretations and organizational context as predictors of corporate choice of environmental strategy. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 681–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graci, S.; Dodds, R. Why go green? The business case of environmental commitment in the Canadian hotel industry. Anatolia 2008, 19, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Kim, S.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, J.H.; Lim, K.T. Relational bonding strategies in the franchise industry: The moderating role of duration of the relationship. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2015, 30, 830–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Dhar, R.L. Effect of green transformational leadership on green creativity: A study of tourist hotels. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, D.A.; Siegel, D.S. Defining the socially responsible leader. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pless, N.M.; Maak, T.; Stahl, G.K. Developing responsible global leaders through international service-learning programs: The Ulyssess experience. Acad. Manag. Learn. Edu. 2011, 10, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maak, T.; Pless, N.M. Responsible leadership in a stakeholder society: A relational perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 66, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, D.A.; Siegel, D.S.; Javidan, M. Components of CEO transformational leadership and corporate social responsibility. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1703–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, K.S.; LaRocca, M.A. Responsible leadership outcomes via stakeholder CSR values: Testing a values-centered model of transformational leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Mayer, D.M.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Workman, K.; Christensen, A.L. Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: The roles of leader-member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. 2011, 115, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; May, D.R.; Avolio, B.J. The impact of ethical leadership behavior on employee outcomes: The roles of psychological empowerment and authenticity. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2004, 11, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbeiss, S.A.; van Knippenberg, D.; Fahrbach, C.M. Doing well by doing good? Analyzing the relationship between CEO ethical leadership and firm performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 635–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, P.M.J.; Kwon, I.W.G.; Stoeberl, P.A.; Baumhart, R. A cross-cultural comparison of ethical attitudes of business managers: India Korea and the United States. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 46, 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 2nd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 9780071439596. [Google Scholar]

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Suh, T.; Kim, K.M. Brand resonance in franchising relationships: A franchisee-based perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3943–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, H.; Hua, N.; Lee, S. Does size matter? Corporate social responsibility and firm performance in the restaurant industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 51, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Palanski, M.E.; Walumbwa, F.O. When leadership goes unnoticed: The moderating role of follower self-esteem on the relationship between ethical leadership and follower behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, L.K.; Weaver, G.R.; Reynolds, S.J. Behavioral ethics in organizations: A review. J. Manag. 2006, 32, 951–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Steidlmeier, P. Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. Leadersh. Q. 1999, 10, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciulla, J.B. Ethics, the Heart of Leadership; Praeger Publishers: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2004; ISBN 9781440830655. [Google Scholar]

- Demirtas, O.; Akdogan, A.A. The effect of ethical leadership behavior on ethical climate, turnover intention, and affective commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanski, M.E.; Yammarino, F.J. Integrity and leadership: A multi-level conceptual framework. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G.A. Leadership in Organizations, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2002; ISBN 9780130323125. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action; Free Press: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986; ISBN 9780138156145. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K. Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Guix, M.; Bonilla-Priego, M.J. Corporate social responsibility in cruising: Using materiality analysis to create shared value. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Kim, Y.; Lee, K.H.; Li, D.X. The impact of CSR on relationship quality and relationship outcomes: A perspective of service employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ma, Q.; Morse, S. Motives for corporate social responsibility in Chinese food companies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallich, H.C.; McGowan, J.J. Stockholder interest and the corporation’s role in social policy. In A New Rationale for Corporate Social Policy; Committee for Economic Development: Washington, DC, USA, 1970; pp. 39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Carini, C.; Comincioli, N.; Poddi, L.; Vergalli, S. Measure the performance with the market value added: Evidence from CSR companies. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, T.; Fenclova, E.; Dinan, C. Tourism and corporate social responsibility: A critical review and research agenda. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 6, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Nor, Y.S.; Choi, J.W.; Kim, S.; Han, S.H.; Lee, J.H. Why does franchisor social responsibility really matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 53, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three dimensional conceptual model of corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horizon. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, E.; Melé, D. Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 53, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Lee, S. Financial rewards for social responsibility: A mixed picture for restaurant companies. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2009, 50, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Cronin, J.J.; Peloza, J. The role of corporate social responsibility in consumer evaluation of nutrition informational disclosure by retail restaurants. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraj-Andrés, E.; Martinez-Salinas, E.; Matute-Vallejo, J. A multidimensional approach to the influence of environmental marketing and orientation on the firm’s organizational performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Benito, J.; González-Benito, Ó. Environmental proactivity and business performance: An empirical analysis. Omega 2005, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.P.; Covin, J.G. Environmental marketing: A source of reputational, competitive, and financial advantage. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 23, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Developing a model of quality management methods and evaluating their effects on business performance. Total Qual. Manag. 2000, 11, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning, Implementation and Control, 8th ed.; Prentice-Hall: London, UK, 1994; ISBN 9780137228515. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, A.; Menon, A.; Chowdhury, J.; Jankovish, J. Evolving paradigm for environmental sensitivity in marketing programs: A synthesis of theory and practice. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 1999, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menguc, B.; Ozanne, L.K. Challenges of the “green imperative”: A natural resource-based approach to the environmental orientation-business performance relationship. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Hull, C.E.; Rothenberg, S. How corporate social responsibility engagement strategy moderates the CSR-financial performance relationship. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 1274–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Brymer, R.A. The effects of ethical leadership on manager job satisfaction, commitment, behavioral outcomes, and firm performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 1020–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.; Schermerhom, J.R.; Dienhart, J.W. Strategic leadership of ethical behavior in business. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2004, 18, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C. Upper echelons theory: An update. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, S.; Hambrick, D.C.; Canella, A.A. Strategic Leadership: Theory and Research on Executives, Top Management Teams, and Boards; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; ISBN 9780195162073. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, M.A.; Geletkanycz, M.A.; Sanders, W.G. Upper echelons research revisited: Antecedents, elements, and consequences of top management team composition. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 749–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.I.; Ashraf, S.; Sarfraz, M. The organizational identification perspective of CSR on creative performance: The moderating role of creative self-efficacy. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.S.; Chiu, C.J.; Yang, C.F.; Pai, D.C. The effects of corporate social responsibility on brand performance: The mediating effect of industrial brand equity and corporate reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L. Stakeholder influence capacity and the variability of financial returns to corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 794–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. The driver of green innovation and green image—Green core competence. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 136–137. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, G. Measuring organizational performance: Beyond the triple bottom line. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2009, 18, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Sun, L.Y.; Leung, A.S.M. Corporate social responsibility, firm reputation, and firm performance: The role of ethical leadership. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2014, 31, 925–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manner, M.H. The impact of CEO characteristics on corporate social performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fair Trade Commission. The Franchise Industry. 2015. Available online: http://franchise.ftc.go.kr/franchise/statistics.jsp (accessed on 10 October 2017).

- Bergeron, F.; Raymond, L.; Rivard, S. Ideal patterns of strategic alignment and business performance. Inf. Manag. 2004, 41, 1003–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E. Organizational Culture and Leadership, 3rd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004; ISBN 9780787968458. [Google Scholar]

- Chosun Biz The ratio of female executives, SK 2%, LG 1.9%...it may be reverse discrimination against males, 2016. Available online: http://biz.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2013/02/18/2013021802217.html (accessed on 8 November 2017).

- Lee, E.M.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, H.J. Employee perception of CSR activities: Its antecedents and consequences. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1716–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angus-Leppan, T.; Metcalf, L.; Benn, S. Leadership styles and CSR practices: An examination of sensemaking, institutional drivers and CSR leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Choi, J.W.; Moon, B.Y.; Babin, B.J. Codes of ethics, corporate philanthropy, and employee responses. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 39, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, P. Food under fire. Nation’s Restaurant News. 17 May 2010, Volume 44, pp. 23–24. Available online: http://www.nrn.com/archive/food-under-fire (accessed on 8 February 2018).

- Farrington, T.; Curran, R.; Gori, K.; O’Gorman, K.D.; Queenan, J. Corporate social responsibility: Reviewed, rated, revised. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarlicki, D.P.; Latham, G.P. Leadership training in organizational justice to increase citizenship behavior within a labor union: A replication. Pers. Psychol. 1997, 50, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenbrunsel, A.E.; Smith-Crowe, K.; Umphress, E.E. Building houses on rocks: The role of the ethical infrastructure in organizations. Soc. Justice Res. 2003, 16, 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.H.; Parsa, H.G.; Self, J. The dynamics of green restaurant patronage. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2010, 51, 344–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maon, F.; Lindgreen, A.; Swaen, V. Designing and implementing corporate social responsibility: An integrative framework grounded in theory and practice. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).