Sustainable Entrepreneurship Orientation: A Reflection on Status-Quo Research on Factors Facilitating Responsible Managerial Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Setting the Stage

2.1. The Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on Entrepreneurship Orientation

2.2. Moving from Entrepreneurial Orientation to Sustainable Entrepreneurial Orientation

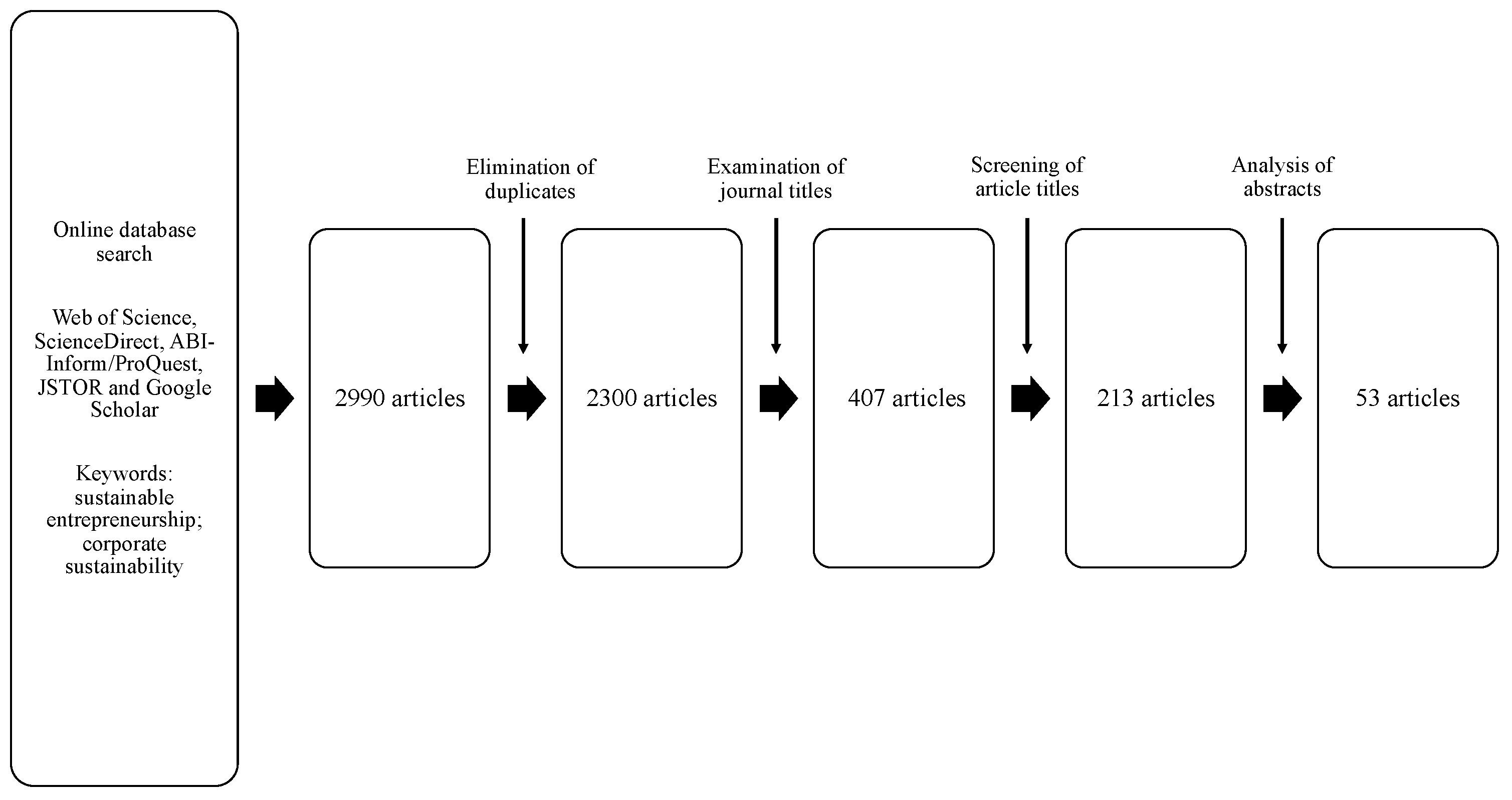

3. Literature Review Approach

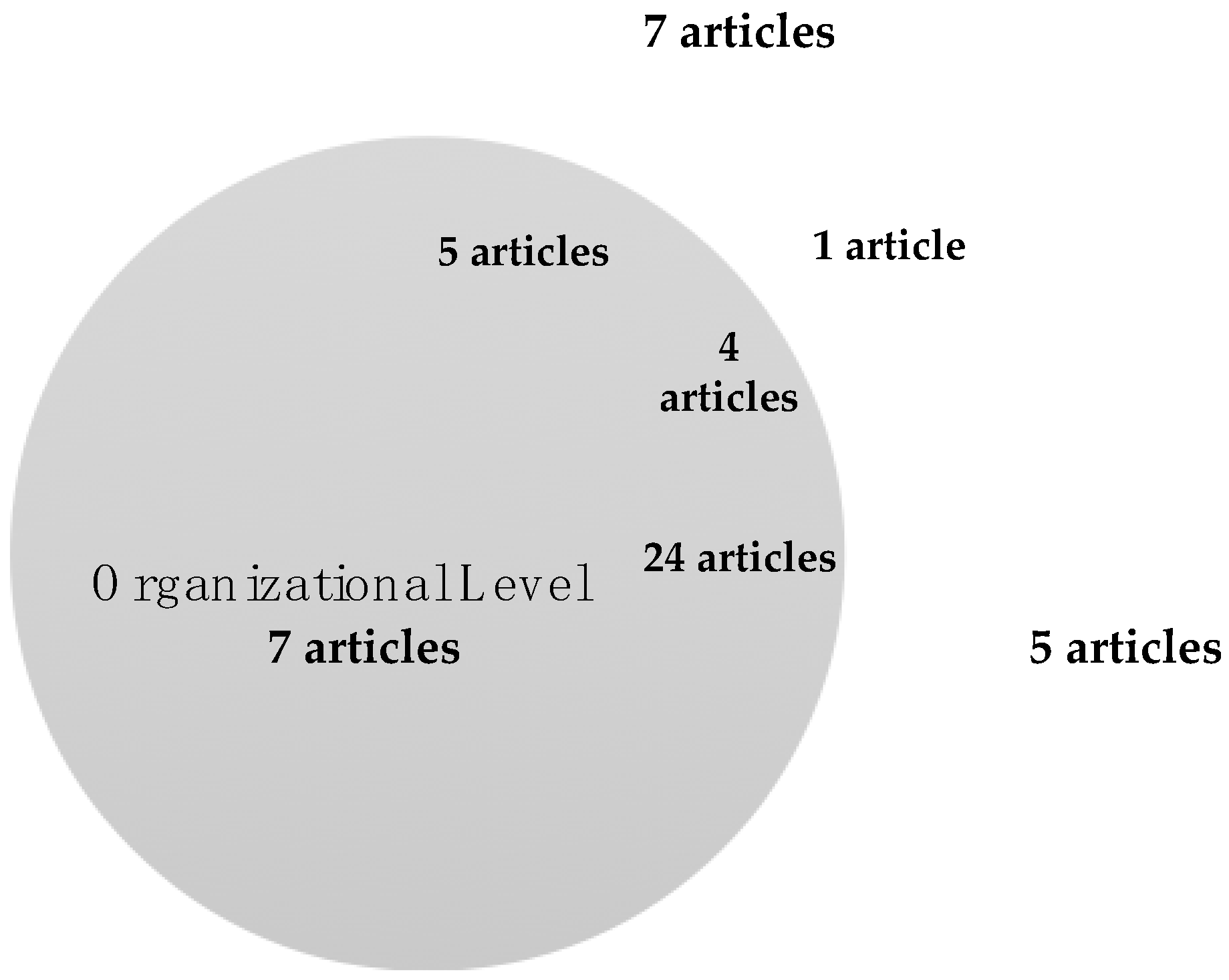

4. Results: Sustainable Entrepreneurial Orientation and the Factors that Facilitate Responsible Managerial Practices

4.1. Individual Level

4.2. Organizational Level

4.3. Contextual/Market Level

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions: Relevance for Theory and Practice and Recommendations for Further Research

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Title | Author | Year | Journal | Level of Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Who takes more sustainability-oriented Entrepreneurial Actions? The Role of Entrepreneurs’ Values, Beliefs and Orientations. | Brem, Bhattacharjee & Jahanshahi | 2017 | Sustainability | Individual |

| Bad Apples in Bad Barrels Revisited: Cognitive Moral Development, Just World Beliefs, Rewards, and Ethical Decision-Making. | Ashkanasy, N.M., Windsor, C.A., & Treviño, L.K. | 2006 | Business Ethics Quarterly | Individual |

| Toward a Typology of New Venture Creators: Similarities and Contrasts Between Business and Social Entrepreneurs | Vega, G., & Kidwell, R.E. | 2007 | New England Journal of Entrepreneurship | Individual |

| What motivates ecopreneurs to start businesses? | Kirkwood, J., & Walton, S. | 2010 | International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research | Individual |

| The Meaning of “Social Entrepreneurship” | Dees | 2001 | Book | Individual/Organizational/Contextual |

| Strategic Entrepreneurship and Managerial Activities in SMEs | Messeghem | 2003 | International Small Business Journal | Individual/Organizational |

| Investigating social entrepreneurship: A multidimensional model | Weerawardena, J., & Mort, G.S. | 2006 | Journal of World Business | Individual/Organizational |

| Sustainable Entrepreneurship: Is Entrepreneurial Will Enough? A North-South Comparison | Spence, M., Gherib, J.B., & Biwolé, V.O. | 2011 | Journal of Business Ethics | Individual/organizational |

| Corporate Sustainability and Innovation in SMEs: Evidence of Themes and Activities in Practice | Bos-Brouwers, H.E.J. | 2010 | Business Strategy and the Environment | Individual/organizational |

| Ecological Entrepreneurship Support Networks: Roles and functions for conversation organizations | Kimmel, C.E., & Hull, R.B. | 2012 | Geoform | Organizational |

| Seeing ecology and “green” innovations as a source of change | Azzone, G., & Noci, G. | 1998 | Journal of Organizational Change Management | Organizational/Contextual |

| Nascent green-technology ventures: A study assessing the role of partnership diversity in firm success | Meysen, M., & Carsrud, A.L | 2013 | Small Business Economics | Organizational/Contextual |

| Beyond green niches? Growth strategies of environmentally-motivated social enterprises | Vickers, I., & Lyon, F. | 2012 | International Small Business Journal | Organizational/Contextual |

| Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Performance: The Case of Italian SMEs | Longo, M., Mura, M., & Bonoli, A. | 2005 | Corporate Governance | Individual/Organizational |

| Green Goliaths versus Emerging Davids—Theorizing about the Role of Incumbents and Entrants in Sustainable Entrepreneurship | Hockerts, K., & Wüstenhagen, R. | 2010 | Journal of Business Venturing | Organizational |

| Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions | Schaltegger, S., & Wagner, M. | 2010 | Business Strategy and the Environment | Organizational |

| Doing business in a green way: A systematic review of the ecological sustainability entrepreneurship literature and future research directions | Gast, J., Gundolf, K., & Cesinger, B. | 2017 | Journal of Cleaner Production | Individual/Organizational/Contextual |

| The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard: Linking Sustainability Management to Business Strategy | Figge, F., Hahn, T., Schaltegger, S., & Wagner, M. | 2002 | Business Strategy and the Environment | Organizational |

| The Influence of Sustainability Orientation on Entrepreneurial Intentions—Investigating the Role of Business Experience | Kuckertz, A., & Wagner, M. | 2010 | Journal of Business Venturing | Individual |

| Social entrepreneurship—A new look at the people and the potential | Thompson, J., Alvy, G., & Lees, A. | 2000 | Management Decision | Individual |

| The venture development processes of ‘‘sustainable’’ entrepreneurs | Choi, D.Y., & Gray, E.R. | 2008 | Management Research News | Organizational/Contextual |

| The environmental–social interface of sustainable development: Capabilities, social capital, institutions. | Lehtonen, M. | 2004 | Ecological Economies | Organizational/Contextual |

| Achieving sustainability through environmental innovation: The role of SMEs. | Biondi, V., Iraldo, F., & Meredith, S. | 2002 | International Journal of Technology Management | Organizational/Contextual |

| Family and Territory Values for a Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Experience of Loccioni Group and Varnelli Distillery in Italy | Del Baldo, M. | 2012 | Journal of Marketing Development and Competitiveness | Indivdual |

| Sustainability through food and conversation: The role of an entrepreneurial restaurateur in fostering engagement with sustainable development issues. | Moskwa, E., Higgins-Desbiolles, F., & Gifford, S. | 2015 | Journal of Sustainable Tourism | Organizational/Contextual |

| Ecological entrepreneurship: Sustainable development in local communities through quality food production and local branding. | Marsden, T., & Smith, E. | 2005 | Geoform | Organizational/Contextual |

| Business Strategies for Effective Entrepreneurship: A Panacea for Sustainable Development and Livelihood in the Family. | Oguonu, C. | 2015 | International Journal of Management and Sustainability | Organizational/Contextual |

| Sustainability Entrepreneurship and Equitable Transitions to a Low-Carbon Economy | Parrish, B.D., & Foxon, T.J. | 2006 | Greener Management International | Organizational/Contextual |

| Supporting Green Entrepreneurship in Romania: Imperative of Sustainable Development | Zamfir, P.B. | 2014 | Romanian Economic and Business Review | Organizational/Contextual |

| Sustainability entrepreneurs—Could they be the True Wealth Generators of the Future? | Tilley, F., & Young, W. | 2006 | Greener Management International | Individual/Contextual |

| Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: Reducing environmental degradation through entrepreneurial action. | Dean, T.J., & McMullen, J.S. | 2007 | Journal of Business Venturing | Individual/Organizational/Contextual |

| Shaping the future: Sustainable innovation and entrepreneurship. | Belz, F.M. | 2013 | Social Business | Organizational/Contextual |

| The transition to the sustainable enterprise | Keijzers, G. | 2002 | Journal of Cleaner Production | Organizational/Contextual |

| Sustainable Innovation through an Entrepreneurship Lens | Larson, A.L. | 2000 | Business Strategy and the Environment | Organizational |

| Environmental Entrepreneurship in Organic Agriculture in Järna | Larson, A.L. | 2012 | Journal of Sustainable Agriculture | Organizational/Contextual |

| Urban development projects catalyst for sustainable transformations: The need for entrepreneurial political leadership. | Block, T., & Paredis, E. | 2013 | Journal of Cleaner Production | Organizational/Contextual |

| Entrepreneurship, management, and sustainable development. | Ahmed, A., & McQuaid, R.W. | 2005 | World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development | Organizational/Contextual |

| Place attachment and social legitimacy: Revisiting the sustainable entrepreneurship journey. | Kibler, E., Fink, M., Lang, R., & Munoz, P. | 2015 | Journal of Business Venturing Insights | Organizational/Contextual |

| Escaping the green prison: Entrepreneurship and the creation of opportunities for sustainable development. | Pacheco, D.F., Dean, T.J., & Payne, D.S. | 2010 | Journal of Business Venturing | Organizational/Contextual |

| Institutional entrepreneurship capabilities for interorganizational sustainable supply chain strategies | Peters, N.J., Hofstetter, J.S., & Hoffmann, V.H. | 2011 | The International Journal of Logistics Management | Organizational/Contextual |

| Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Corporate Political Activity: Overcoming Market Barriers in the Clean Energy Sector. | Pinkse, J., & Groot, K. | 2015 | Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice | Organizational/Contextual |

| Greening regions: The effect of social entrepreneurship, co-decision and co-creation on the embrace of good sustainable development practices | Barrutia, J.M., & Echebarria, C. | 2012 | Journal of Environmental Planning and Management | Organizational/Contextual |

| Sustainable valley entrepreneurial ecosystems | Cohen, B. | 2005 | Business Strategy and the Environment | Organizational/Contextual |

| Redefining innovation: Eco-innovation research and the contribution from ecological economies | Rennings, K. | 2000 | Ecological Economies | Organizational |

| Entrepreneurial Orientation: A Business Strategic Approach for Sustainable Development | Criado-Gomis, A., Cervera-Taulet, A., & Iniesta-Bonillo, M.A. | 2017 | Sustainability | Organizational |

| Sustainable corporate entrepreneurship | Miles, M.P., Munilla, L.S., & Darroch, J. | 2009 | International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal | Contextual |

| Sustainable Consumption: Opportunities for Consumer Research and Public Policy | Prothero, A., Dobscha, S., Freung, J., Kilbourne, W.E., Luchs, M.G., Qzanne, L.K., & Thogersen, J. | 2011 | Journal of Public Policy & Marketing | Contextual |

| Family and Territory Values for a Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Experience of Loccioni Group and Varnelli Distillery in Italy | Del Baldo, M. | 2012 | Journal of Marketing Development and Competitiveness | Individual/Organizational/Contextual |

| No Money? No Problem! The Value of Sustainability: Social Capital Drives the Relationship among Customer Identification and Citizenship Behavior in Sharing Economy | Wang, Y.B., & Ho, C.W. | 2017 | Sustainability | Organizational/Contextual |

| Consumer responses to corporate social responsibility in China | Tian, Z., Wang, R., & Yang, W. | 2011 | Journal of Business Ethics | Contextual |

| The entrepreneurship factor in sustainable tourism development | Lordkipanidze, M., Brezet, H., & Backman, M | 2005 | Journal of Cleaner Production | Contextual |

| The entrepreneur-environment nexus: Uncertainty, innovation and allocation | York, J.G., & Venkataraman, S. | 2010 | Journal of Business Venturing | Organizational/Contextual |

| The Rationality and Irrationality of Financing Green Start-Ups | Bergset, L. | 2015 | Administrative Sciences | Contextual |

References

- Archarya, V.V.; Richardson, M. Causes of the Financial Crisis. J. Politics Soc. 2009, 21, 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2014, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenster, N.; Bauer, R.; Derwall, J.; Koedijk, K. The Economy Value of Corporate Eco-Efficiency. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2011, 17, 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Daneke, G.; Lenox, M. Sustainable development and entrepreneurship: Past contributions and future directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellnhofer, K.; Kraus, S.; Bouncken, R.B. The Current State of Research on Sustainable Entrepreneurship. Int. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 14, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gast, J.; Gundolf, K.; Cesinger, B. Doing business in a green way: A systematic review of the ecological sustainability entrepreneurship literature and future research directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, B.; Winn, M.I. Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melay, I.; Kraus, S. Green Entrepreneurship: Definition of Related Concepts. Int. J. Strateg. Manag. 2012, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Berle, G. The Green Entrepreneur: Business Opportunities That Can Save the Earth and Make You Money; Liberty Hall Press: Blue Ridge, PA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.C.; Malin, S. Green Entrepreneurship: A Method for Managing Natural Resources? Soc. Nat. Resour. 2008, 21, 828–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, J.G. The Meaning of Social Entrepreneurship; Standford University: Standford, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, J.; Marti, I. Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Gonin, M.; Besharov, M.L. Managing Social-Business Tensions. Bus. Ethics Q. 2013, 23, 407–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, T.W.; Short, J.C.; Payne, G.T.; Lumpkin, G.T. Dual identities in social ventures: An exploratory study. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 805–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaak, R. Green Logic: Ecopreneurship, Theory and Ethics; Routledge: West Hartford, CT, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 20, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallaster, C. Managing a Company Crisis through Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: A Practice-based Analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D.; Wright, P.M. Corporate Social Responsibility: Strategic Implications. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Siegel, D.S.; Waldman, D.A. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Sustainability. Bus. Soc. 2011, 50, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloza, J.; Shang, J. How can corporate social responsibility activities create value for stakeholders? A systematic review. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruyaka, O.; Zeitzmann, H.; Chalamon, I.; Wokutch, R.; Thakur, P. Strategic corporate social responsibility and orphan drug development: Insights from the US and the EU biopharmaceutical industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 117, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquier, A.; Valiorgue, B.; Daudigeos, T. Sharing the shared value: A transaction cost perspective on strategic CSR policies in global value chains. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A.; Mauser, A. The Evolution of Environmental Management: From Stage Models to Performance Evaluation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M.; Gherib, J.B.; Biwolé, V.O. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: Is Entrepreneurial Will Enough? A North-South Comparison. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 99, 335–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Lugo, A.E. Rehabilitation of Tropical Lands: A Key to Sustaining Development. Restor. Energy 1994, 2, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.E.; Cobb, J.B.; Cobb, C.W. For the Common Good: Redirecting the Economy toward Community, the Environment, and a Sustainable Future; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Littig, B.; Griessler, E. Social sustainability: A catchword between political pragmatism and social theory. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 8, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Office. Report VI: The Promotion of Sustainable Enterprises, International Labour Conference—96th Session; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, D.Y.; Gray, E.R. The venture development processes of ‘‘sustainable’’ entrepreneurs. Manag. Res. News 2008, 31, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.; Freeman, R. Stakeholders, social responsibility, and performance: Empirical evidence and theoretical perspectives. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.; Smith, N. Corporate social responsibility audits: Doing well by doing good. Sloan Manag. Rev. 2000, 41, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational Stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J.; Harris, K.E. Do consumers expect companies to be socially responsible? The impact of corporate social responsibility on buying behavior. J. Consum. Aff. 2001, 35, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Carpenter, A.; Huisingh, D. A review of ‘theories of the firm’ and their contributions to Corporate Sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, M.R.; Porter, M.E. Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S.; Rigtering, J.C.; Hughes, M.; Hosman, V. Entrepreneurial orientation and the business performance of SMEs: A quantitative study from the Netherlands. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2012, 6, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strateg. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huarng, K.H.; Yu, T.H.K. Entrepreneurship, process innovation and value creation by a non-profit SME. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29, 770–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A. Predictors and financial outcomes of corporate entrepreneurship: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Ventur. 1991, 6, 259–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, B.R.; Schuhmacher, F. Do socially (ir)responsible investments pay? New evidence from international ESG data. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2016, 59, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huarng, K.H.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.E. Developmental management: Theories, methods, and applications in entrepreneurship, innovation, and sensemaking. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Tur, A.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. The level of innovation among young innovative companies: The impacts of knowledge-intensive services use, firm characteristics and the entrepreneur attributes. Serv. Bus. 2014, 8, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein Woolthuis, R.J.A. Sustainable entrepreneurship in the Dutch construction industry. Sustainability 2010, 2, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, T.J.; McMullen, J.S. Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: Reducing environmental degradation through entrepreneurial action. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirzner, I.M. Competition and Entrepreneurship; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholders Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, C. The Functions of the Executive; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Bos-Brouwers, H.E.J. Corporate Sustainability and Innovation in SMEs: Evidence of Themes and Activities in Practice. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 19, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D.; Toledano, N.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. Socio-cultural factors and transnational entrepreneurship: A multiple case study in Spain. Int. Small Bus. J. 2011, 29, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Lumpkin, G.T. Entrepreneurial orientation theory and research: Reflections on a needed construct. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 855–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. A conceptual model of entrepreneurship as firm behavior. Entrep. Crit. Perspect. Bus. Manag. 1991, 3, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Miller, D. International entrepreneurial orientation: Conceptual considerations, research themes, measurement issues, and future research directions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 11–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Wiklund, J.; Lumpkin, G.T.; Frese, M. Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 761–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the Entrepreneurial Orientation Construct and linking it to Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 135–172. [Google Scholar]

- Eggers, F.; Kraus, S.; Jensen, S.H.; Rigtering, J.P.C. A comparative analysis of the entrepreneurial orientation/growth relationship in service firms and manufacturing firms. Serv. Ind. J. 2014, 34, 275–294. [Google Scholar]

- Low, M.B.; MacMillan, I.C. Entrepreneurship: Past research and future challenges. J. Manag. 1988, 14, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.H.; Kuratko, D.F.; Covin, J.G. Corporate Entrepreneurship & Innovation; Thomson Higher Education: Mason, OH, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D.; Friesen, P.H. Strategy making and environment: The third link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1983, 4, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, A.; Kubea, H.; Schmidt, S.; Flatten, C. Entrepreneurial orientation in turbulent environments: The moderating role of absorptive capacity. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1353–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, K.; Mentzer, J.T.; Ozsomer, A. The effects of entrepreneurial proclivity and market orientation on business performance. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasser, S.M.; Rammerstorfer, M.; Weinmayer, K. Markowitz revisited: Social portfolio engineering. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 258, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, C.; Sinha, R.K.; Kumar, A. Market orientation and alternative strategic orientations: A longitudinal assessment of performance implications. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Wagner, M. The Influence of Sustainability Orientation on Entrepreneurial Intentions—Investigating the Role of Business Experience. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parboteeah, K.P.; Addae, H.M.; Cullen, J.B. Propensity to support sustainability initiatives: A cross-national model. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keijzers, G. The transition to the sustainable enterprise. J. Clean. Prod. 2002, 10, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakala, H. Strategic orientations in management literature: Three approaches to understanding the interaction between market, technology, entrepreneurial and learning orientations. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.; Jaju, A.; Puzakova, M.; Rocereto, J.F. The Connubial Relationship between Market Orientation and Entrepreneurial Orientation. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2013, 21, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criado-Gomis, A.; Cervera-Taulet, A.; Iniesta-Bonillo, M.A. Sustainable Entrepreneurial Orientation: A Business Strategic Approach for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; McQuaid, R.W. Entrepreneurship, management, and sustainable development. World Rev. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 1, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figge, F.; Hahn, T.; Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard: Linking Sustainability Management to Business Strategy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguonu, C. Business Strategies for Effective Entrepreneurship: A Panacea for Sustainable Development and Livelihood in the Family. Int. J. Manag. Sustain. 2015, 4, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brem, A.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Jahanshahi, A.A. Who Takes More Sustainability-Oriented Entrepreneurial Actions? The Role of Entrepreneurs’ Values, Beliefs and Orientations. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1636. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkanasy, N.M.; Windsor, C.A.; Treviño, L.K. Bad Apples in Bad Barrels Revisited: Cognitive Moral Development, Just World Beliefs, Rewards, and Ethical Decision-Making. Bus. Ethics Q. 2006, 16, 449–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egri, C.P.; Herman, S. Leadership in the North American Environmental Sector: Values, Leadership Styles, and Contexts of Environmental Leaders and their Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 571–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, J.; Walton, S. What motivates ecopreneurs to start businesses? Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2010, 16, 204–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A.L. Sustainable Innovation through an Entrepreneurship Lens. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2000, 9, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, G.; Kidwell, R.E. Toward a Typology of New Venture Creators: Similarities and Contrasts Between Business and Social Entrepreneurs. N. Engl. J. Entrep. 2007, 10, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Baldo, M. Family and Territory Values for a Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Experience of Loccioni Group and Varnelli Distillery in Italy. J. Mark. Dev. Compet. 2012, 6, 120–139. [Google Scholar]

- Tilley, F.; Young, W. Sustainability entrepreneurs—Could they be the True Wealth Generators of the Future? Greener Manag. Int. 2006, 55, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.; Alvy, G.; Lees, A. Social entrepreneurship—A new look at the people and the potential. Manag. Decis. 2000, 38, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C. Upper Echelons Theory: An Update. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper Echelons: The Organization as a Reflection of Its Top Managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, H. Corporate social responsibility and the mining industry: Conflicts and constructs. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2004, 11, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messeghem, K. Strategic Entrepreneurship and Managerial Activities in SMEs. Int. Small Bus. J. 2003, 21, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, G.A. Cross-cultural reliability and validity of a scale to measure firm entrepreneurial orientation. J. Bus. Ventur. 1997, 12, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennings, K. Redefining innovation: Eco-innovation research and the contribution from ecological economies. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 32, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, F.M. Shaping the future: Sustainable innovation and entrepreneurship. Soc. Bus. 2013, 3, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardena, J.; Mort, G.S. Investigating social entrepreneurship: A multidimensional model. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, C.G.; Chaganti, R. Businesses without glamour? An analysis of resources on performance by size and age in small service and retail firms. J. Bus. Ventur. 1999, 14, 233–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosakowski, E.A. Resource-Based Perspective on the Dynamic Strategy-Performance Relationship: An Empirical Examination of the Focus and Differentiation Strategies in Entrepreneurial Firms. J. Manag. 1993, 19, 819–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.; Gartner, W.B. Properties of Emerging Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 429–441. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, B.; Geraudel, M.; Mothe, C. Generating Business Referrals for SMEs: The Contingent Value of CEOs Social Capital. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2013, 52, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, A.; Salaff, J.W. Social Networks and Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 28, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, C.E.; Hull, R.B. Ecological Entrepreneurship Support Networks: Roles and functions for conversation organizations. Geoforum 2012, 43, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Wang, R.; Yang, W. Consumer responses to corporate social responsibility in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 101, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, T.; Paredis, E. Urban development projects catalyst for sustainable transformations: The need for entrepreneurial political leadership. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzone, G.; Noci, G. Seeing ecology and “green” innovations as a source of change. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 1998, 11, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, E.; Fink, M.; Lang, R.; Munoz, P. Place attachment and social legitimacy: Revisiting the sustainable entrepreneurship journey. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2015, 3, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meysen, M.; Carsrud, A.L. Nascent green-technology ventures: A study assessing the role of partnership diversity in firm success. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 739–759. [Google Scholar]

- Vickers, I.; Lyon, F. Beyond green niches? Growth strategies of environmentally-motivated social enterprises. Int. Small Bus. J. 2012, 32, 449–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, D.F.; Dean, T.J.; Payne, D.S. Escaping the green prison: Entrepreneurship and the creation of opportunities for sustainable development. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, N.J.; Hofstetter, J.S.; Hoffmann, V.H. Institutional entrepreneurship capabilities for interorganizational sustainable supply chain strategies. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2011, 22, 52–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkse, J.; Groot, K. Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Corporate Political Activity: Overcoming Market Barriers in the Clean Energy Sector. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 633–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrutia, J.M.; Echebarria, C. Greening regions: The effect of social entrepreneurship, co-decision and co-creation on the embrace of good sustainable development practices. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2012, 55, 1348–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B. Sustainable valley entrepreneurial ecosystems. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2005, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, M. Environmental Entrepreneurship in Organic Agriculture in Järna, Sweden. J. Sustain. Agric. 2012, 36, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, D.; Gilmore, A.; Rocks, S. SME Marketing Networking: A Strategic Approach. Strateg. Chang. 2004, 13, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, V.; Iraldo, F.; Meredith, S. Achieving sustainability through environmental innovation: The role of SMEs. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2002, 24, 612–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, M.; Mura, M.; Bonoli, A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Performance: The Case of Italian SMEs. Corp. Gov. 2005, 5, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockerts, K.; Wüstenhagen, R. Green Goliaths versus Emerging Davids—Theorizing about the Role of Incumbents and Entrants in Sustainable Entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtonen, M. The environmental–social interface of sustainable development: Capabilities, social capital, institutions. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 49, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Sustainable Competitive Advantage: Combining Institutional and Resource-Based Views. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Tarí, J.J.; Pereira-Moliner, J.; López-Gamero, M.D.; Pertusa-Ortega, E.M. The effects of quality and environmental management on competitive advantage: A mixed methods study in the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, G. Pro-environmental Behavior in Egypt: Is there a Role for Islamic Environmental Ethics? J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 65, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.P.; Munilla, L.S.; Darroch, J. Sustainable corporate entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2009, 5, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prothero, A.; Dobscha, S.; Freung, J.; Kilbourne, W.E.; Luchs, M.G.; Qzanne, L.K.; Thogersen, J. Sustainable Consumption: Opportunities for Consumer Research and Public Policy. J. Public Policy Mark. 2011, 30, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.B.; Ho, C.W. No Money? No Problem! The Value of Sustainability: Social Capital Drives the Relationship among Customer Identification and Citizenship Behavior in Sharing Economy. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahme, U. Sharing Economy, CSR and Sustainability: Making the Connection—I. 2017. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/sharing-economy-csr-sustainability-making-connection-i-unmesh-brahme (accessed on 30 October 2017).

- Pineiro-Chousa, J.; Vizcaíno-González, M.; López-Cabarcos, M. Reputation, Game Theory and Entrepreneurial Sustainability. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineiro-Chousa, J.; Vizcaíno-González, M.; López-Cabarcos, M.Á.; Romero-Castro, N. Managing Reputational Risk through Environmental Management and Reporting: An Options Theory Approach. Sustainability 2017, 9, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lordkipanidze, M.; Brezet, H.; Backman, M. The entrepreneurship factor in sustainable tourism development. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastakia, A. Grassroots ecopreneurs: Change agents for a sustainable society. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 1998, 11, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergset, L. The Rationality and Irrationality of Financing Green Start-Ups. Adm. Sci. 2015, 5, 260–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskwa, E.; Higgins-Desbiolles, F.; Gifford, S. Sustainability through food and conversation: The role of an entrepreneurial restaurateur in fostering engagement with sustainable development issues. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T.; Smith, E. Ecological entrepreneurship: Sustainable development in local communities through quality food production and local branding. Geoforum 2005, 36, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, B.D.; Foxon, T.J. Sustainability Entrepreneurship and Equitable Transitions to a Low-Carbon Economy. Greener Manag. Int. 2006, 55, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamfir, P.B. Supporting Green Entrepreneurship in Romania: Imperative of Sustainable Development. Romanian Econ. Bus. Rev. 2014, 9, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- York, J.G.; Venkataraman, S. The entrepreneur-environment nexus: Uncertainty, innovation and allocation. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez Olugbola, S. Exploring entrepreneurial readiness of youth and startup success components: Entrepreneurship training as a moderator. J. Innov. Knowl. 2017, 2, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, M.T.; Tortora, D.; Mazzucchelli, A.; Festa, G.; Di Gregorio, A.; Metallo, G. Impacts of Code of ethics on financial performance in the Italian listed companies of bank sector. J. Bus. Account. Financ. Perspect. 2018, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S.; Burtscher, J.; Niemand, T.; Roig-Tierno, N.; Syrjä, P. Configurational Paths to Social Performance in SMEs: The Interplay of Innovation, Sustainability, Resources and Achievement Motivation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Niemand, T.; Halberstadt, J.; Shaw, E.; Syrjä, P. Social entrepreneurship orientation: development of a measurement scale. Int. J. Entrepr. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 977–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kraus, S.; Burtscher, J.; Vallaster, C.; Angerer, M. Sustainable Entrepreneurship Orientation: A Reflection on Status-Quo Research on Factors Facilitating Responsible Managerial Practices. Sustainability 2018, 10, 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020444

Kraus S, Burtscher J, Vallaster C, Angerer M. Sustainable Entrepreneurship Orientation: A Reflection on Status-Quo Research on Factors Facilitating Responsible Managerial Practices. Sustainability. 2018; 10(2):444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020444

Chicago/Turabian StyleKraus, Sascha, Janina Burtscher, Christine Vallaster, and Martin Angerer. 2018. "Sustainable Entrepreneurship Orientation: A Reflection on Status-Quo Research on Factors Facilitating Responsible Managerial Practices" Sustainability 10, no. 2: 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020444

APA StyleKraus, S., Burtscher, J., Vallaster, C., & Angerer, M. (2018). Sustainable Entrepreneurship Orientation: A Reflection on Status-Quo Research on Factors Facilitating Responsible Managerial Practices. Sustainability, 10(2), 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020444