Towards Sustainable Neighborhoods: Challenges and Opportunities for Neighborhood Planning in Transitional Urban China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background Theory

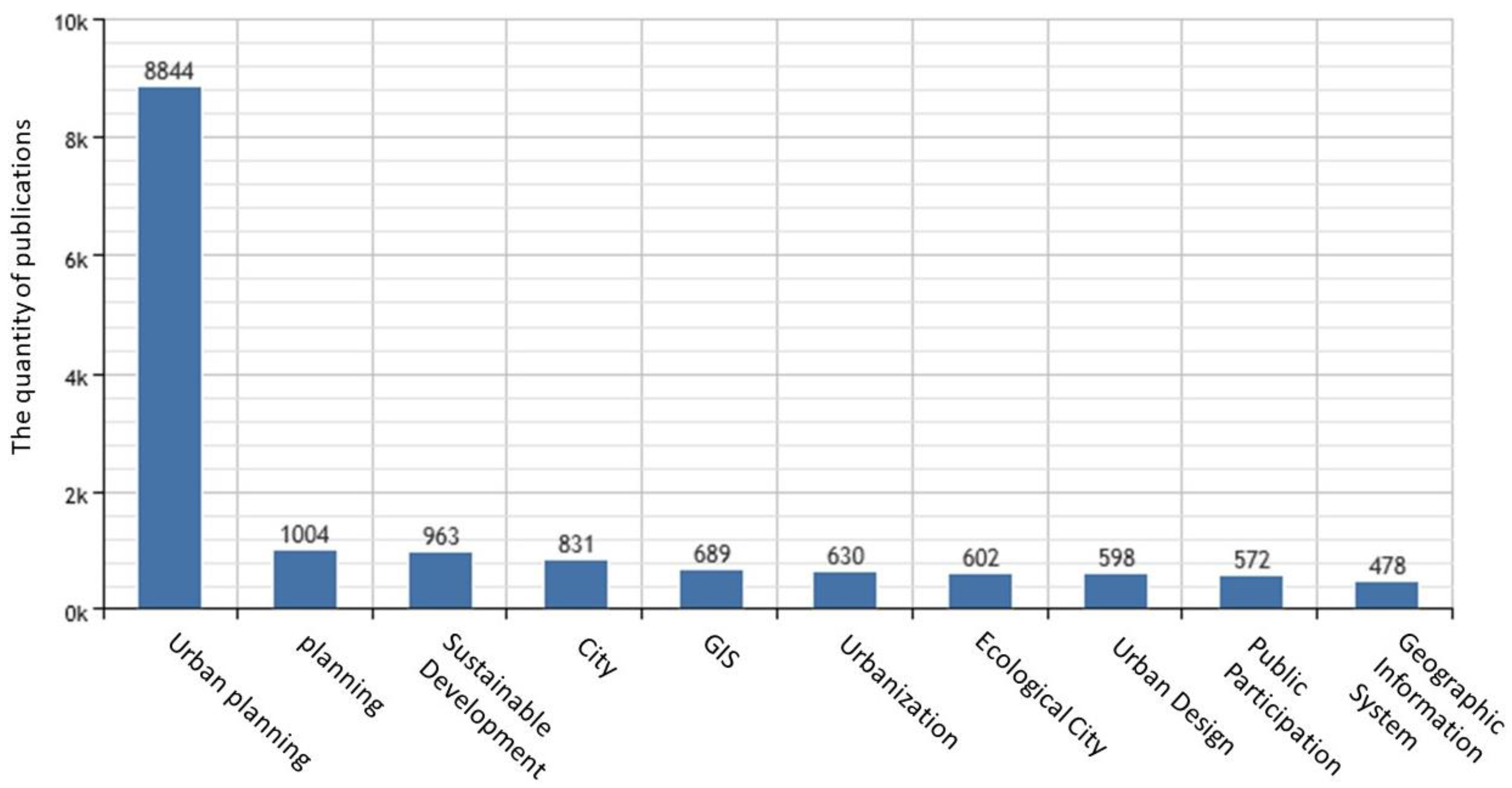

2.1. Neighborhood Concept and Neighborhood Planning

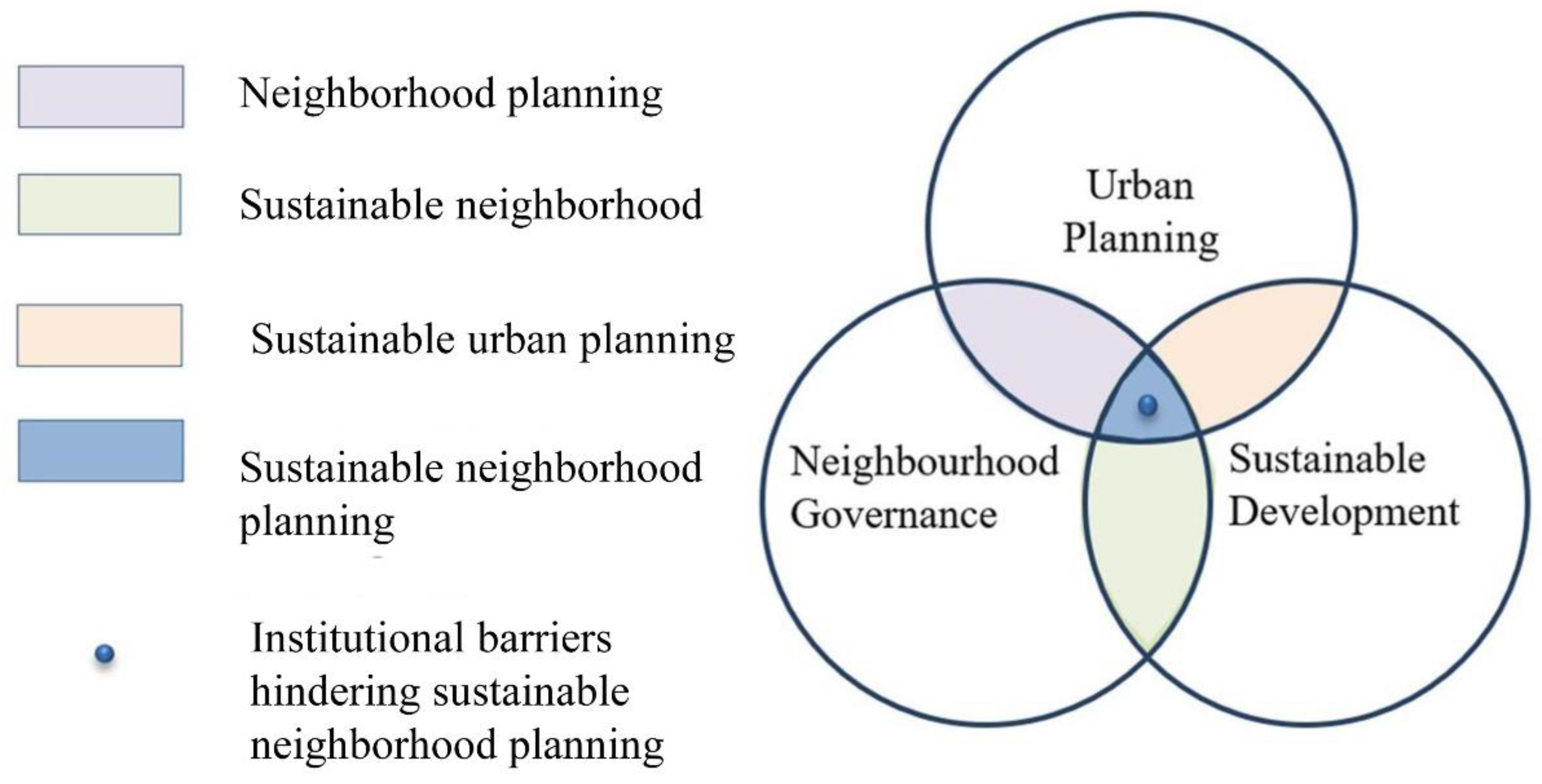

2.2. Institutional Aspects of Neighborhood Planning to Achieve Neighborhood Sustainability

3. The China Context

3.1. Emerging Urban Sustainability Challenges and Measures

3.2. Major Urban Planning Issues Concerning Sustainable Development and Neighborhood

3.3. Neighborhood Transition and Governance in Contemporary China

3.3.1. The Danwei Compound and Its Dissolution (1950s–1980s)

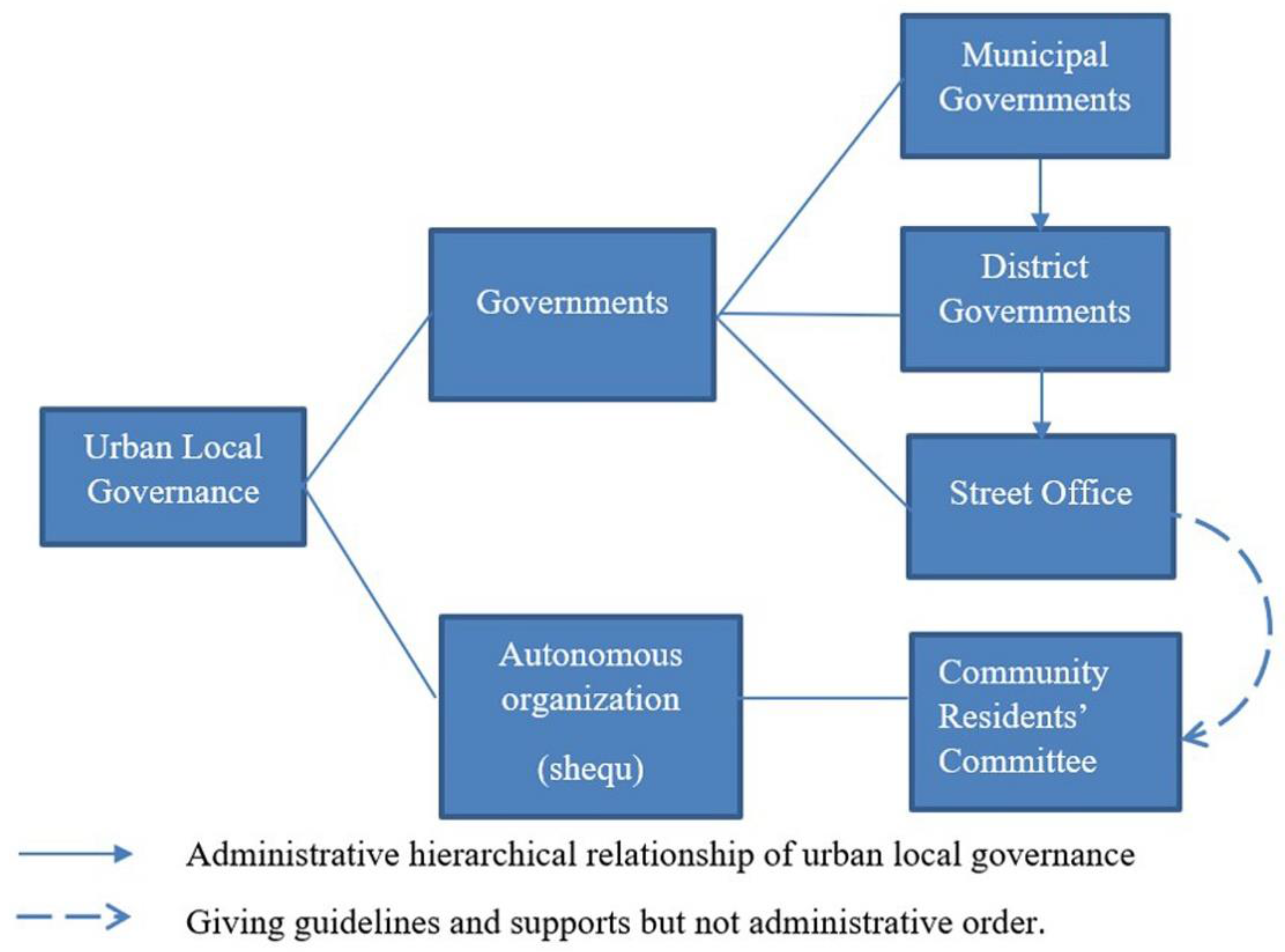

3.3.2. ‘Community Building’ and the Local Governance (1990s–Present)

3.4. The Prominence of Institutional Elements in Sustainable Neighborhood Planning in China

4. Methods

4.1. Comparative Study of Neighborhood Planning in Four Countries

4.2. Expert Interview

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Common Characteristics of Neighborhood Planning in Other Countries

5.2. Barriers to Neighborhood Planning Development in China

5.2.1. Insufficient Policy Design and Legal Support

5.2.2. Inappropriate Local Governance and Planning Context

5.2.3. Weak Sense of Community and Participation in Planning

6. Policy Implications and Recommendations

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Agenda 21: The Rio Declaration on Environment and Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/outcomedocuments/agenda21 (accessed on 7 December 2017).

- Camagni, R. On the concept of territorial competitiveness: Sound or misleading? Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 2395–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabrew, L.; Wiek, A.; Ries, R. Environmental decision making in multi-stakeholder contexts: Applicability of life cycle thinking in development planning and implementation. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauscher, R.C.; Momtaz, S. Conclusions and directions for sustainable neighborhood planning. In Sustainable Neighborhoods of Australia; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 193–201. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development (UNCSD). Report of the World Summit on Sustainable Development; United Nations Publication: Johannesburg, South Africa, 26 August–4 September 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Satterthwaite, D. Successful, safe and sustainable cities: Towards a New Urban Agenda. Commonw. J. Local Gov. 2017, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choguill, C.L. Developing sustainable neighborhoods. Habitat Int. 2008, 32, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohe, W.M. From local to global: One hundred years of neighborhood planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2009, 75, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyoko, C.; Cooper, R.; Davey, C.; Wootton, A. Addressing sustainability early in the urban design process. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2006, 17, 689–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Murayama, A. A critical review of seven selected neighborhood sustainability assessment tools. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2013, 38, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin, A.; Spangenberg, J.H. A guide to community sustainability indicators. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2000, 20, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J.; Fang, C. Towards Sustainable Neighborhoods: The Role of Social Planning in China—A Case Study of Ningbo, Zhejiang Province. City Plan. Rev. 2011, 1, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, P.; Xia, T. Inspiration from pilot community planning of Wulian in Longgang district of Shenzhen. City Plan. Rev. 2009, 4, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Fu, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, L. Some thinking on Sustainability of residential district Planning. Urban Plan. Forum 2008, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Q.; Yu, T.; Zuo, J.; Lai, X. Challenges of developing sustainable neighborhoods in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 972–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.H.D. Restructuring for growth in urban China: Transitional institutions, urban development, and spatial transformation. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Breitung, W.; Li, S. The Changing Meaning of Neighborhood Attachment in Chinese Commodity Housing Estates: Evidence from Guangzhou. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wei, Y.D.; Liao, F.H.; Huang, Z. Administrative hierarchy and urban land expansion in transitional China. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 56, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garde, A. Sustainable by design: Insights from US LEED-ND pilot projects. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2009, 75, 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Berardi, U. Sustainability assessment of urban communities through rating systems. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2013, 15, 1573–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, J.H.; Pfahl, S.; Deller, K. Towards indicators for institutional sustainability: Lessons from an analysis of Agenda 21. Ecol. Indic. 2002, 2, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, C.A. City planning for neighborhood life. Soc. Forces 1929, 8, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, B.; Leighton, B. Networks, neighborhoods, and communities: Approaches to the study of the community question. Urban Aff. Q. 1979, 14, 363–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostic, R.W.; Martin, R.W. Black home-owners as a gentrifying force? Neighborhood dynamics in the context of minority home-ownership. Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 2427–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaskin, R.J.; Garg, S. The issue of governance in neighborhood-based initiatives. Urban Aff. Rev. 1997, 32, 631–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Rogers, G.O. Neighborhood planning theory, guidelines, and research: Can area, population, and boundary guide conceptual framing? J. Plan. Lit. 2015, 30, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.M.; Hou, Q.; Chen, S.; Zhou, C. Work, home, and market: The social transformation of housing space in Guangzhou, China. Urban Geogr. 2010, 31, 434–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, Q. The Political Identities of Neighborhood Planning in England. Space Polity 2015, 19, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How to Prepare a Neighborhood Plan. Available online: https://planninghelp.cpre.org.uk/improve-where-you-live/shape-your-local-area/neighborhood-plans/how-to-prepare-a-neighborhood-plan (accessed on 30 January 2018).

- Sirianni, C. Neighborhood planning as collaborative democratic design: The case of Seattle. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2007, 73, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoney, C.; Elgersma, S. Neighborhood Planning through Community Engagement: The Implications for Place Based Governance and Outcomes. In Proceedings of the Canadian Political Science Association, Saskatoon, Canada, May/June 2007; Available online: https://carleton.ca/cure/wp-content/uploads/Stoney_Elgersma_2007.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2017).

- Evans, B.; Joas, M.; Sundback, S.; Theobald, K. Governing Sustainable Cities; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Awortwi, N. An unbreakable path? A comparative study of decentralization and local government development trajectories in Ghana and Uganda. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2011, 77, 347–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakumba, U. Local government citizen participation and rural development: Reflections on Uganda’s decentralization system. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2010, 76, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, L. Using empowerment and social inclusion for pro-poor growth: A theory of social change. In Working Draft of Background Paper for the Social Development Strategy Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, R.; Zhou, T. Decentralization in a centralized system: Project-based governance for land-related public goods provision in China. Land Use Policy 2015, 47, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, J. Communicating a Politics of Sustainable Development; Eolss Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W. Critical social sustainability factors in urban conservation: The case of the central police station compound in Hong Kong. Facilities 2012, 30, 396–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.J.; Wiek, A.; Bergmann, M.; Stauffacher, M.; Martens, P.; Moll, P.; Swilling, M.; Thomas, C.J. Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, E.D.; Dougill, A.J.; Mabee, W.E.; Reed, M.; McAlpine, P. Bottom up and top down: Analysis of participatory processes for sustainability indicator identification as a pathway to community empowerment and sustainable environmental management. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 78, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drilling, M.; Schnur, O. Nachhaltigkeit in der Quartiersentwicklung–einführendeAnmerkungen; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012; pp. 11–41. [Google Scholar]

- Talen, E. Sprawl retrofit: Sustainable urban form in unsustainable places. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2011, 38, 952–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bess, K.D.; Fisher, A.T.; Sonn, C.C.; Bishop, B.J. Introduction. In Psychological Sense of Community: Research, Applications and Implications; Fisher, A.T., Sonn, C.C., Bishop, B.J., Eds.; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2002; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, S.; Aubry, T.; Coulombe, D. Neighborhoods and neighbours. Do they contribute to personal well-being? J. Community Psychol. 2004, 32, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prezza, M.; Constantini, S. Sense of community and life satisfaction: Investigation in three different territorial contexts. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 8, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwakkel, J.H.; Van der Pas, J.W.G.M. Evaluation of infrastructure planning approaches: An analogy with medicine. Futures 2011, 43, 934–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, R.R.; Driebe, D.J. Uncertainty and Surprise in Complex Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Marique, A.F.; Reiter, S. Towards more sustainable neighborhoods: Are good practices reproducible and extensible? A review of a few existing sustainable neighborhoods. In Proceedings of the 27th Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 13–15 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- National Development and Reform Commission. National Report on Sustainable Development Report. Available online: http://www.china-un.org/eng/zt/sdreng/P020120608816970051133.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2017).

- Liu, H.; Zhou, G.; Wennersten, R.; Frostell, B. Analysis of sustainable urban development approaches in China. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Luo, Y. Community Planning and the Local Approach in the Perspective of Social Governance Innovation—A Case Study of Shiyou Road, Yuzhong District of Chongqing. J. Hum. Settl. West China 2014, 5, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Zhao, M. From Residential Area Planning to Community Planning. Urban Plan. Forum 2002, 06, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Yung, E.H.; Chan, E.H.; Zhu, D. Issues of NIMBY conflict management from the perspective of stakeholders: A case study in Shanghai. Habitat Int. 2016, 53, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.Y.; Tao, D.K. Exploring and Thinking Over the Public Participation in Urban Plan Formulation in The New Period: A Case Study of Nanjing Master Plan Revision. City Plan. Rev. 2012, 2, 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Walder, A. The informal dimension of enterprise financial reforms. China’s Econ. Looks Year 2000 1986, 1, 630–645. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.; Li, L.C. Community governance reform in urban China: A case study of the Yantian model in Shenzhen. J. Comp. Asian Dev. 2012, 11, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.Z. An empirical study on self-governing organizations in new-style urban communities. Soc. Sci. China 2008, 29, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F. Gated communities and migrant enclaves: The conundrum for building ‘harmonious community/shequ’. J. Contemp. China 2008, 17, 633–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derleth, J.; Koldyk, D. The Shequ Experiment: Grassroots political reform in urban China. J. Contemp. China 2004, 13, 747–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Hu, L.; Guo, J.; Cook, I.G. China’s urban planning in transition. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Urban Des. Plan. 2014, 167, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogner, A.; Menz, W. The theory-generating expert interview: Epistemological interest, forms of knowledge, interaction. In Interviewing Experts; Bogner, A., Littig, B., Menz, W., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009; pp. 43–80. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, K. Neighborhood Sustainability Assessment: Connecting Impact with Policy Intent. 2015. Available online: http://rem-main.rem.sfu.ca/theses/BirdKiri_2015_MRM620.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2017).

- Planning Practice Guidance. Available online: http://planningguidance.communities.gov.uk/blog/guidance/neighborhood-planning/ (accessed on 15 December 2017).

- Seattle Department of Neighborhoods. 2016. Available online: https://www.seattle.gov/neighborhoods/programs-and-services/neighborhood-planning (accessed on 15 December 2017).

- A Guide for Developing Neighborhood Plans. Manitoba Intergovernmental Affairs and the City of Winnipeg’s Planning, Property and Development Department -Planning and Land Use Division. 2002. Available online: http://www.winnipeg.ca/ppd/pdf_files/Nhbd_guide.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2017).

- Community Empowerment Network, Taipei. Available online: http://en.community-taipei.tw/introduction.jsp (accessed on 15 December 2017).

- Worldometers. Available online: http://www.worldometers.info/population/ (accessed on 15 December 2017).

- House, A.E.; House, B.J.; Campbell, M.B. Measures of interobserver agreement: Calculation formulas and distribution effects. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 1981, 3, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinhua News Agency. CPC Central Committee and Central Government’s Advice on Enhancing and Improving Urban-Rural Neighborhood Governance. Available online: http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2017-06/12/c_1121130511.htm (accessed on 1 December 2017).

- Yu, K.H.; Cai, H. A research on community planning system reconstruction and new mechanism in China from the perspective of low-carbon. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 7, 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Shen, G.Q.; Feng, J.; Wu, Y. Delivering a low-carbon community in China: Technology vs. strategy. Habitat Int. 2013, 37, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Qian, X.; Zhang, L. Public participation in environmental management in China: Status quo and mode innovation. Environ. Manag. 2015, 55, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.Y.; Deng, X.Y. Community planning based on socio-spatial production: Explorations in “new qinghe experiment”. City Plan. Rev. 2016, 11, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, C. Policy and praxis of land acquisition in China. Land Use Policy 2007, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The Order of Steps | Eight Steps to Prepare a Neighborhood Plan | Links with Sustainability Appraisal |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Getting started | |

| 2 | Identify the issues | Identify key economic, social and environmental issues. |

| 3 | Develop a vision and objectives | Identify key national planning framework and local planning objectives Develop the sustainability framework (objectives and criteria) |

| 4 | Generate options | Appraise the options using the sustainability framework |

| 5 | Draft your neighborhood plan | Appraise the draft policies using the sustainability framework |

| 6 | Consultation and submission | Prepare the sustainability appraisal report |

| 7 | Independent examination | |

| 8 | Referendum and adoption |

| Comparision of Aspect | UK | US | Canada | Taiwan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urbanization Rate (By urban population in 2016) | 80.8% | 83.2% | 81.9% | 77% |

| Is NP a legal planning? | Yes | No | No | No |

| Is the form of NP diverse or normative? | Normative | Diverse | Diverse | Diverse |

| What is the Status of NP in the Local Development? | The adopted plan becomes a part of statutory development plan | It varies from state to state. In a few states, an adopted plan become a component of city’s development plan. | The adopted plan becomes an official guideline for neighborhood development | An official scheme to engage public into neighborhood development. |

| Which Local Body is Responsible for the NP Projects? | Parish or town council; or Neighborhood forum; or Community organization | City council | City council | Community Empowerment Network (Founded by Municipal Government) |

| Applied Neighborhood Sustainability Assessment Tools | 1. BREEAM Communities 2. SPeAR 3. OPL | 1. LEED-ND 2. ECC 3. EPAT 4. CS | 1. FSA Tool 2. SCORE Tool | EEWH-EC |

| Expert | Name | Field of expertise | Affiliation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mr AA | Civil Affairs and Community Governance | Senior Governor, District Government, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China. |

| 2 | Dr BB | Urban and Community Planning | Professor, The University of XX, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China. |

| 3 | Ms CC | Urban Planning and Design | Senior Planner, a professional urban planning and design Institute, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China. |

| 4 | Dr DD | Public Space Management and Policy | Professor, The University of YY, UK. |

| 5 | Dr EE | Planning Methodology and Technology | Senior Researcher, The University of ZZ, Shanghai, China. |

| 6 | Ms FF | Urban Renewal and Public Participation | Project Manager, a renowned NGO, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China. |

| 7 | Dr GG | Green Technology and Environmental Regulation | Professor, The University of UU, Beijing, China. |

| 8 | Dr HH | Elderly Friendly Community | Director of A professional planning and design institute, Shanghai, China. |

| 9 | Dr II | Neighborhood and Participatory Planning | Professor, The University of VV, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China. |

| 10 | Mr JJ | Community Governance | Director of XX Community, Chengdu, China. |

| 11 | Dr KK | Urban Planning | Senior Urban Planner, Urban Planning and Design Institute of XX city, Jiangsu, China. |

| 12 | Dr LL | Urban Design and residential area planning | Former chief planner of Urban Planning and Design institute, XX city, Hubei, China |

| Institutional Aspect | No. | Aspects for Comparison | Key Common Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decentralization and local governance | 1 | The aim or role of Neighborhood Plan |

|

| 2 | Relationship to regional or other upper-level planning (How the Neighborhood Plan fits into the Planning System) | ||

| 3 | The coverage of neighborhood plan practice in the country | ||

| 4 | Is Neighborhood Plan a Statutory Plan? (Legitimacy?) | ||

| 5 | Financial and Human Resources of Neighborhood Planning Projects | ||

| Iterative and adaptive planning | 6 | Who is the facilitator of neighborhood planning project? |

|

| 7 | Planning Horizon, any regular revision? | ||

| 8 | How will the plan be used to guide neighborhood development? | ||

| Cultivation of community sense | 9 | Neighborhood Profile |

|

| 10 | Core Concerns; Key Issues to be addressed | ||

| 11 | The range of community engagement activity | ||

| Public Participation and decision making | 12 | The degree of public participation |

|

| 13 | Major Factors of the plan | ||

| 14 | Institutional arrangement of planning procedure |

| No. | Specific Barrier | Total Consent Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Weak sense of comunity | 87.5% |

| 2 | Lack of national policy foundation and explicit official definition | 75% |

| 3 | Unclear accountable body of neighborhood planning project | 75% |

| 4 | Lack of institutional arrangement or Resolution mechanism of planning conflicts | 50% |

| 5 | Inadequate experience, degree and platform of public participation | 100% |

| 6 | Inadequate financial and human resource support | 75% |

| 7 | Lack of the facilitation of Steering Committee | 50% |

| 8 | Lack of institution and mechanism for planning implementation and evaluation | 75% |

| 9 | Planning procedure is not normalized, systematic and iterative | 75% |

| Other barriers suggested by the experts: | ||

| S1 | Inadequate updated laws and regulations to define the authority and liability of neighborhood public space management | |

| S2 | Highly bureaucratic community residents’ committee | |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Q.; Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W. Towards Sustainable Neighborhoods: Challenges and Opportunities for Neighborhood Planning in Transitional Urban China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020406

Zhang Q, Yung EHK, Chan EHW. Towards Sustainable Neighborhoods: Challenges and Opportunities for Neighborhood Planning in Transitional Urban China. Sustainability. 2018; 10(2):406. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020406

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Qi, Esther Hiu Kwan Yung, and Edwin Hon Wan Chan. 2018. "Towards Sustainable Neighborhoods: Challenges and Opportunities for Neighborhood Planning in Transitional Urban China" Sustainability 10, no. 2: 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020406

APA StyleZhang, Q., Yung, E. H. K., & Chan, E. H. W. (2018). Towards Sustainable Neighborhoods: Challenges and Opportunities for Neighborhood Planning in Transitional Urban China. Sustainability, 10(2), 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020406