The Impact of Flipped Learning on Cooperative and Competitive Mindsets

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Is the effect of flipped learning also appropriate to business education as with chemistry, engineering, algebra, nursing, and so on?

- (2)

- What changes will students experience through the attainment of flipped learning for sustainability?

- (3)

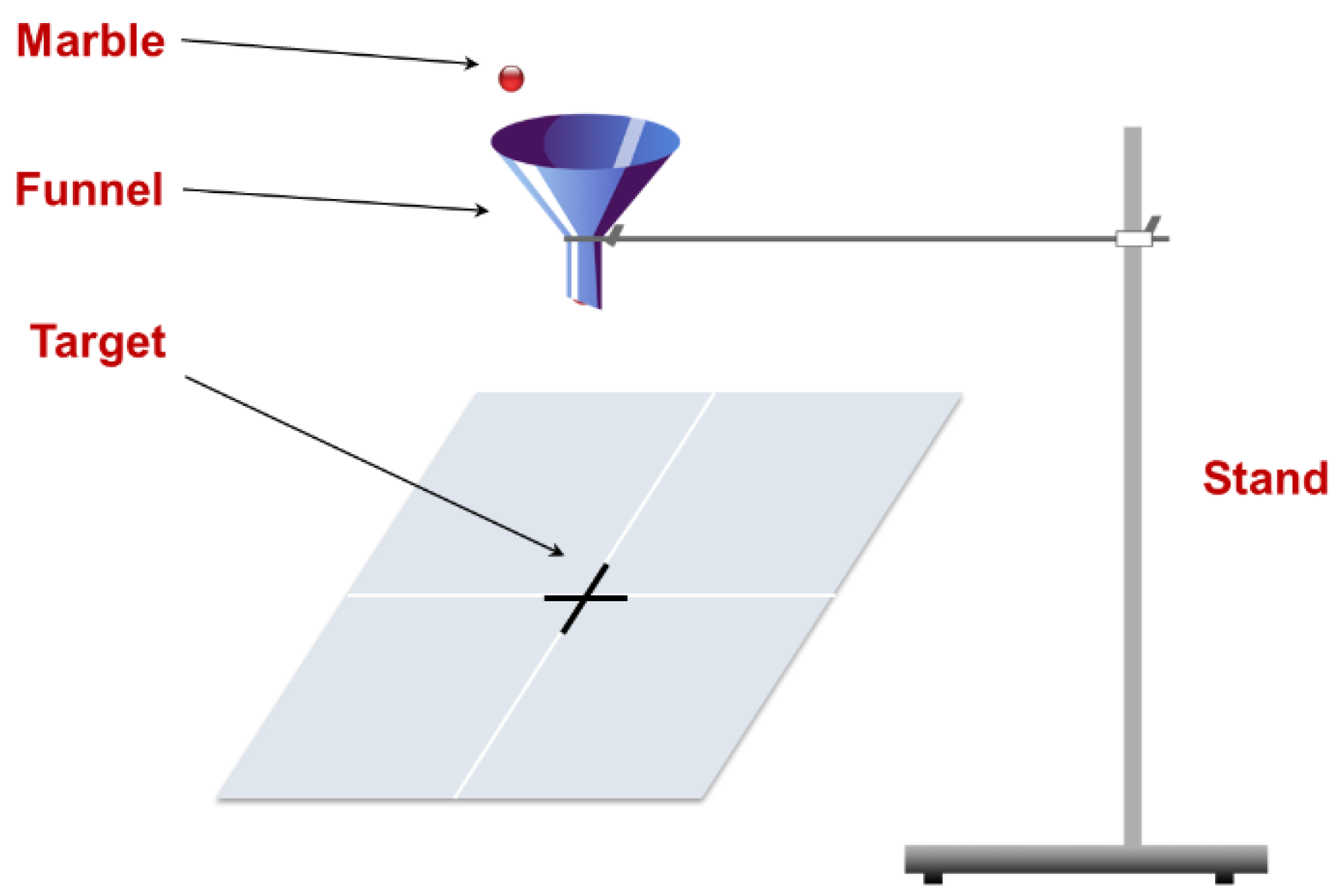

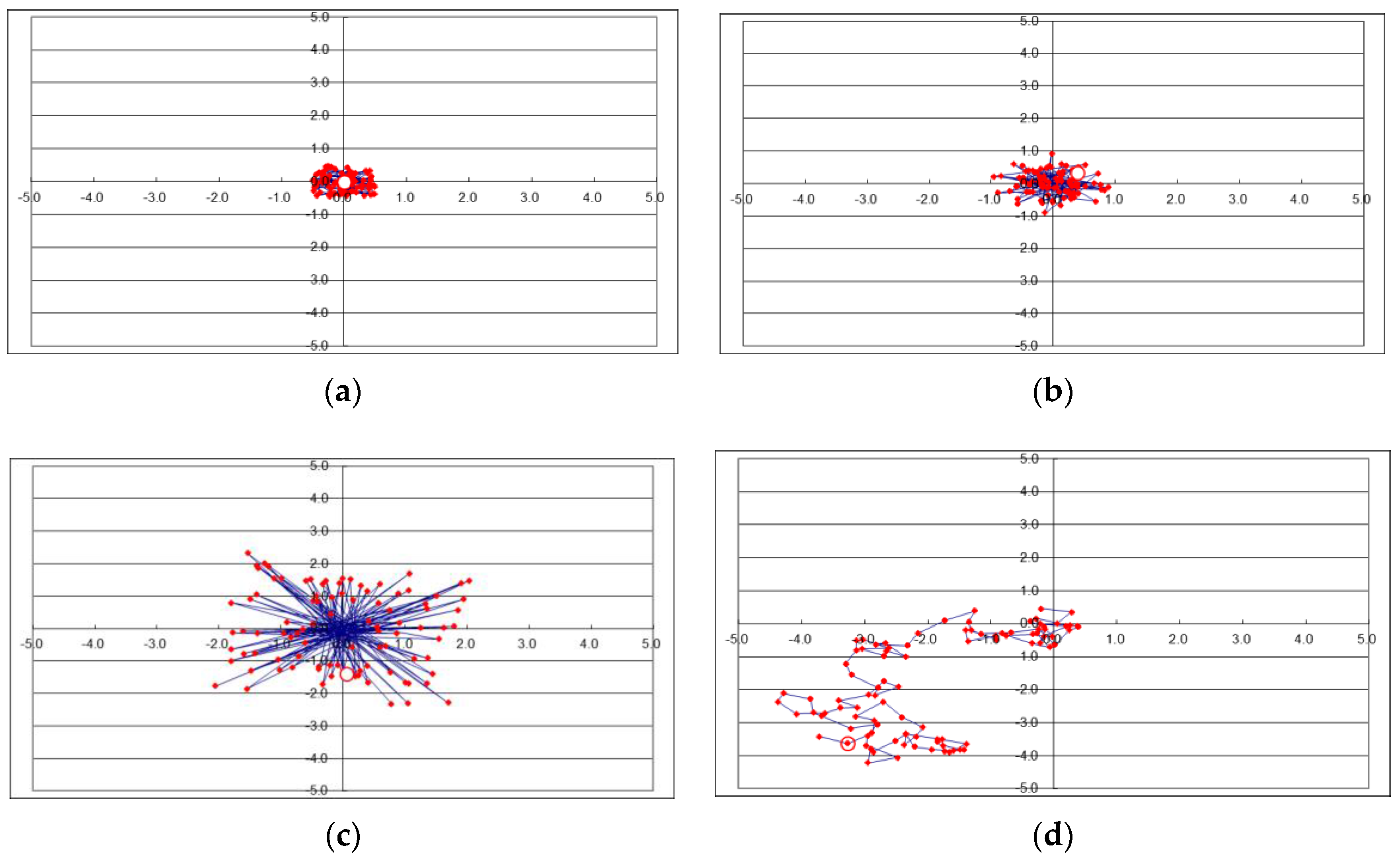

- Is Nelson’s funnel experiment effective as a pre-learning material for flipped learning?

2. Background

2.1. Flipped Learning

2.2. The Funnel Experiment

2.3. Corporate Sustainability Education

3. Flipped Learning Design and Data Collection

4. Analysis and Results

“In rule 1, I was able to identify the importance of the real purpose…the mission in business. The ‘WHY’ should be kept unchanged compared to ‘HOW’ or ‘WHAT.’ In rule 3 and 4, it needs to be a higher concept, such as creating a new social value; not just winning in competition.”“This (experiment) was very fun. Similar to this experiment, too much resource development can result in a ‘Butterfly Effect.’ Especially in natural development, we should be careful about unconditionally following or competing against rival countries or companies.”“I learned the usefulness of benchmarking last semester. Benchmarking seems to be effective from a reasonable point of view. However, it is interesting that unconditionally following an advanced company is not always good benchmarking—at least not according to Rule 4.”“Very impressive. I was able to see how terrible the consequences of unconditionally competing against a competitor are in Rule 3. The way to prevent bleeding competition is to keep your own principles.”“This experiment showed us not to be glad now, but sad now. I saw the failure of ‘management by exception.’ Responding to all the deviations, without focusing on the high impact deviations, turned out even worse ... The unconditional diligence without exception was poisonous.”

5. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, L.; Mason, K.; Hibbert, P.; Rivers, C. Management education in turbulent times. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 41, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter-morland, M. Philosophical assumptions undermining responsible management education. J. Manag. Dev. 2015, 34, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakas, F.; Manisaligil, A.; Sarigollu, E. Management learning at the speed of life: Designing reflective, creative, and collaborative spaces for millenials. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2015, 13, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, A.A.S.G.; Shaikh, K.H.; Naqvi, S.A.H.; Shaikh, F.M. Impact of case study method of teaching on the job performance of business graduates, in the case of business administration department IBA-University of Sindh-Jamshoro. Aust. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2011, 1, 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ladyshewsky, R.K. The virtual professor and online teaching, administration and research: Issues for globally dispersed business faculty. Int. J. E-Learn. Distance Educ. 2016, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker, J.; New, J.R.; Ireland, R.D. MOOCs and the online delivery of business education what’s new? What’s not? What now? Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2016, 15, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltsos, J.R. Gamification in the business communication course. Bus. Prof. Commun. Q. 2017, 80, 194–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, T. The advance of the MOOCs (massive open online courses): The impending globalisation of business education? Educ. Train. 2013, 55, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A.B. Action learning: Lecturers, learners, and managers at the center of management education. In Human Centered Management in Executive Education; Lepeley, M.-T., von Kimakowitz, E., Bardy, R., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 219–233. ISBN 978-1-137-55540-3. [Google Scholar]

- Seeman, C. Action learning in business education: Goals, impact, and global perspectives. Tick. Acad. Bus. Librariansh. Rev. 2015, 1, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Madden, L.T.; Smith, A.D. Using photographs to integrate liberal arts learning in business education. J. Manag. Educ. 2015, 39, 116–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwombeki, A. Multimedia technologies for business education augmentation in higher learning institutions. Int. J. Comput. Inf. Technol. 2016, 5, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, M.; Vibert, C. Cases for the net generation: An empirical examination of students’ attitude toward multimedia case studies. J. Educ. Bus. 2016, 91, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay-Thompson, S.; Mombourquette, P. Evaluation of a flipped classroom in an undergraduate business course. Bus. Educ. Accredit. 2014, 6, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- King, C.; Piotrowski, C. E-learning and flipped instruction integration in business education: A proposed pedagogical model. J. Instr. Pedagog. 2015, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, W.; Halvorson, W.; Sadeque, S.; Johnston, S. A large class engagement (LCE) model based on service-dominant logic (SDL) and flipped classrooms. Educ. Res. Perspect. 2014, 41, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Progresses; Harvard University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978; ISBN 0-674-57629-2. [Google Scholar]

- Thai, N.T.T.; De Wever, B.; Valcke, M. The impact of a flipped classroom design on learning performance in higher education: Looking for the best “blend” of lectures and guiding questions with feedback. Comput. Educ. 2017, 107, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, A.M. From passive to active: The impact of the flipped classroom through social learning platforms on higher education students’ creative thinking. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2015, 46, 1133–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vliet, E.A.; Winnips, J.C.; Brouwer, N. Flipped-class pedagogy enhances student metacognition and collaborative-learning strategies in higher education but effect does not persist. Life Sci. Educ. 2015, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landrum, N.E.; Ohsowski, B. Content trends in sustainable business education: An analysis of introductory courses in the USA. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2017, 18, 385–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerónimo Silvestre, W.; Antunes, P.; Leal Filho, W. The corporate sustainability typology: Analysing sustainability drivers and fostering sustainability at enterprises. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritala, P.; Sainio, L.-M. Coopetition for radical innovation: Technology, market and business-model perspectives. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2014, 26, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W.; Cocklin, C. Teaching sustainability to business students: Shifting mindsets. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundiers, K.; Wiek, A. Do we teach what we preach? An international comparison of problem- and project-based learning courses in sustainability. Sustainability 2013, 5, 1725–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deming, W.E. Out of the Crisis; MIT Center for Advanced Engineering Study: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986; ISBN 0-262-54115-7. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, R.S.; Field, J.B.F. Using Deming’s funnel experiment to demonstrate effects of violating assumptions underlying Shewhart’s control charts. Am. Stat. 2000, 54, 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Howley, P.P. Teaching how to calibrate a process using experimental design and analysis: The ballistat. J. Stat. Educ. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.M.; Glascoff, M.A. Process measures: A leadership tool for management. TQM J. 2014, 26, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, A. Student views on the use of a flipped classroom approach: Evidence from Australia. Bus. Educ. Accredit. 2014, 6, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Karabulut-Ilgu, A.; Jaramillo Cherrez, N.; Jahren, C.T. A systematic review of research on the flipped learning method in engineering education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covill, D.; Patel, B.A.; Gill, D.S. Flipping the classroom to support learning: An overview of flipped class from science, engineering and product design. Sch. Sci. Rev. 2013, 95, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sams, A.; Bergmann, J. Flip your students’ learning. Educ. Leadersh. 2013, 70, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, J.; Sams, A. Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day; International Society for Technology in Education: Eugene, OR, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-564-84315-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, J.L.; Verleger, M.A. The flipped classroom: A survey of the research. In Proceedings of the 120th ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Atlanta, GA, USA, 23–26 June 2013; American Society for Engineering Education: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Franqueira, V.N.L.; Tunnicliffe, P. To flip or not to flip: A critical interpretive synthesis of flipped teaching. In Smart Education and Smart E-Learning; Uskov, V.L., Howlett, R.J., Jain, L.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 41, pp. 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Zuber, W.J. The flipped classroom, a review of the literature. Ind. Commer. Train. 2016, 48, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nederveld, A.; Berge, Z.L. Flipped learning in the workplace. J. Workplace Learn. 2015, 27, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankey, M.; Hunt, L. Flipped university classrooms: Using technology to enable sound pedagogy. J. Cases Inf. Technol. 2014, 16, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.H. An exploration of online behaviour engagement and achievement in flipped classroom supported by learning management system. Comput. Educ. 2017, 114, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilboy, M.B.; Heinerichs, S.; Pazzaglia, G. Enhancing student engagement using the flipped classroom. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.C.Y.; Wu, Y.T.; Lee, W.I. The effect of the flipped classroom approach to OpenCourseWare instruction on students’ self-regulation. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2017, 48, 713–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, R.S.; Dean, D.L.; Ball, N. Flipping the classroom and instructional technology integration in a college-level information systems spreadsheet course. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2013, 61, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayer, J.F. How learning in an inverted classroom influences cooperation, innovation and task orientation. Learn. Environ. Res. 2012, 15, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, T. Student perceptions toward flipped learning: New methods to increase interaction and active learning in economics. Int. Rev. Econ. Educ. 2014, 17, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frydenberg, M. Flipping excel. Inf. Syst. Educ. J. 2013, 11, 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bösner, S.; Pickert, J.; Stibane, T. Teaching differential diagnosis in primary care using an inverted classroom approach: Student satisfaction and gain in skills and knowledge. BMC Med. Educ. 2015, 15, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmaadaway, M.A.N. The effects of a flipped classroom approach on class engagement and skill performance in a blackboard course. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathula, H.; Lowe, K. The role of the flipped classroom in business education: Linking learning with the workplace. In Proceedings of the 29th Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management Conference, Queenstown, New Zealand, 2–4 December 2015; Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management: Queenstown, New Zealand, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, G.; Ben-Gal, I. The funnel experiment: The Markov-based SPC approach. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2007, 23, 899–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, P. Instrument adjustment policies. NCSLI Meas. J. Meas. Sci. 2016, 11, 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, M.D. Using a spreadsheet version of Deming’s funnel experiment in quality management and OM classes. Decis. Sci. J. Innov. Educ. 2010, 8, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deming, W.E. The New Economics for Industry, Government, Education, 2nd ed.; MIT Center for Advanced Engineering Study: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; ISBN 9780911379075. [Google Scholar]

- Benn, S.; Dunphy, D.; Griffiths, A. Organizational Change for Corporate Sustainability, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 041569549X. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, M.; Bergman, Z.; Berger, L. An empirical exploration, typology, and definition of corporate sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, I.; Hasnaoui, A. The meaning of corporate social responsibility: The vision of four nations. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 419–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.; Kramer, M. Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M.; Porter, M. Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Montabon, F.; Pagell, M.; Wu, Z. Making sustainability sustainable. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2016, 52, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Yu, Y. The influence of perceived corporate sustainability practices on employees and organizational performance. Sustainability 2014, 6, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakos, L.; Dumitrașcu, D. Holonic crisis handling model for corporate sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Suzuki, M.; Carpenter, A.; Tyunina, O. An analysis of the contribution of Japanese business terms to corporate sustainability: Learnings from the “looking-glass” of the East. Sustainability 2017, 9, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburger, A.M.; Nalebuff, B.J. Co-Opetition; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1996; ISBN 0385479506. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, M.G.; Singh, K.N. Servitization, coopetition, and sustainability: An operations perspective in aviation industry. Vikalpa 2017, 42, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Christ, K.L.; Burritt, R.L.; Varsei, M. Coopetition as a potential strategy for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2017, 26, 1029–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, G. A methodology for teaching industrial ecology. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2007, 8, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shephard, K. Higher education for sustainability: Seeking affective learning outcomes. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shephard, K.; Smith, N.; Deaker, L.; Harraway, J.; Broughton-Ansin, F.; Mann, S. Comparing different measures of affective attributes relating to sustainability. Environ. Educ. Res. 2011, 17, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, C.H.; Wehner, E.A.; Tucker, S.S.; King, C.S. The cooperative/competitive strategy scale: A measure of motivation to use cooperative or competitive strategies for success. J. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 128, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Au, W.T.; Jiang, F.; Xie, X.F.; Yam, P. Cooperativeness and competitiveness as two distinct constructs: Validating the cooperative and competitive personality scale in a social dilemma context. Int. J. Psychol. 2013, 48, 1135–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugard, P.; Todman, J. Analysis of pre-test-post-test control group designs in educational research. Educ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Yu, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, X. The measurement of cooperative and competitive personality. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2006, 38, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Chomeya, R. Quality of psychology test between Likert scale 5 and 6 points. J. Soc. Sci. 2010, 6, 399–403. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, T. Deming’s quality experiments revisited. Inf. Trans. Educ. 2007, 8, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zientek, L.; Nimon, K.; Hammack-Brown, B. Analyzing data from a pretest-posttest control group design: The importance of statistical assumptions. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2016, 40, 638–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L.R.; Wegener, D.T.; MacCallum, R.C.; Strahan, E.J. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.M.; Saccuzzo, D.P. Psychological Testing: Principles, Applications, and Issues, 7th ed.; Thompson Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0495095552. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 0-8058-0283-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANCOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, C.J. An effect size primer: A guide for clinicians and researchers. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2009, 40, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tews, M.J.; Michel, J.W.; Noe, R.A. Does fun promote learning? The relationship between fun in the workplace and informal learning. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 98, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabricatore, C.; López, X. Sustainability learning through gaming: An exploratory study. Electron. J. E-Learn. 2012, 10, 209–222. [Google Scholar]

- DeHaan, R.L. Teaching creative science thinking. Science 2011, 334, 1499–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enfield, J. Looking at the impact of the flipped classroom model of instruction on undergraduate multimedia students at CSUN. Techtrends 2013, 57, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stage | Treatment |

|---|---|

| 1. Preparation (D − 2 week) | Pre-measurement: cooperative/competitive mindset scales |

| 2. Pre-class (D − 1 week) | Funnel experiment introduction and practice

|

| 3. In-class (D day) | Topic of discussion:

|

| 4. Post-class (D + 1 week) | Post-measurement: cooperative/competitive mindset scales |

| Factors | Group | N | Pre-Test | Post-Test | Mean Difference | Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||||

| Cooperative mindset | Treatment | 81 | 3.50 | 0.82 | 4.04 | 0.99 | 0.54 | 0.45 |

| Control | 76 | 3.54 | 0.79 | 3.63 | 0.90 | 0.09 | 0.08 | |

| Overall | 157 | 3.52 | 0.80 | 3.84 | 0.96 | 0.32 | 0.27 | |

| Competitive mindset | Treatment | 81 | 3.62 | 0.89 | 3.07 | 0.95 | −0.55 | −0.44 |

| Control | 76 | 3.73 | 1.00 | 3.58 | 0.99 | −0.15 | −0.11 | |

| Overall | 157 | 3.67 | 0.95 | 3.31 | 1.00 | −0.36 | −0.27 | |

| Source | SS | df | MS | F | p-Value | Partial η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 8.38 | 2 | 4.19 | 4.72 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Intercept | 86.81 | 1 | 86.81 | 97.88 | 0.00 | 0.39 |

| Pre-test | 1.80 | 1 | 1.80 | 2.03 | 0.16 | 0.01 |

| Group | 6.74 | 1 | 6.74 | 7.60 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Error | 136.58 | 154 | 0.89 | |||

| Total | 2465.08 | 157 |

| Source | SS | df | MS | F | p-Value | Partial η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 11.52 | 2 | 5.76 | 6.19 | 0.00 | 0.07 |

| Intercept | 85.22 | 1 | 85.22 | 91.52 | 0.00 | 0.37 |

| Pre-test | 1.34 | 1 | 1.34 | 1.44 | 0.23 | 0.01 |

| Group | 9.73 | 1 | 9.73 | 10.45 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Error | 143.40 | 154 | 0.93 | |||

| Total | 1879.67 | 157 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kwon, J.E.; Woo, H.R. The Impact of Flipped Learning on Cooperative and Competitive Mindsets. Sustainability 2018, 10, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010079

Kwon JE, Woo HR. The Impact of Flipped Learning on Cooperative and Competitive Mindsets. Sustainability. 2018; 10(1):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010079

Chicago/Turabian StyleKwon, Jung Eon, and Hyung Rok Woo. 2018. "The Impact of Flipped Learning on Cooperative and Competitive Mindsets" Sustainability 10, no. 1: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010079

APA StyleKwon, J. E., & Woo, H. R. (2018). The Impact of Flipped Learning on Cooperative and Competitive Mindsets. Sustainability, 10(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010079