Electrochemotherapy in the Management of Vascular Malformations: An Updated Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Nonthermal Mechanism: Unlike radiofrequency or laser-based treatments, ECT does not rely on extreme temperatures, reducing the risk of thermal damage to healthy surrounding tissues.

- Enhanced Precision: Electroporation parameters and drug delivery can be targeted to the malformation’s geometry, potentially resulting in fewer adverse effects.

- Cosmetic Preservation: Minimally invasive electrode placement and local bleomycin injection frequently yield favorable cosmetic results, particularly important in head-and-neck or visible cutaneous lesions.

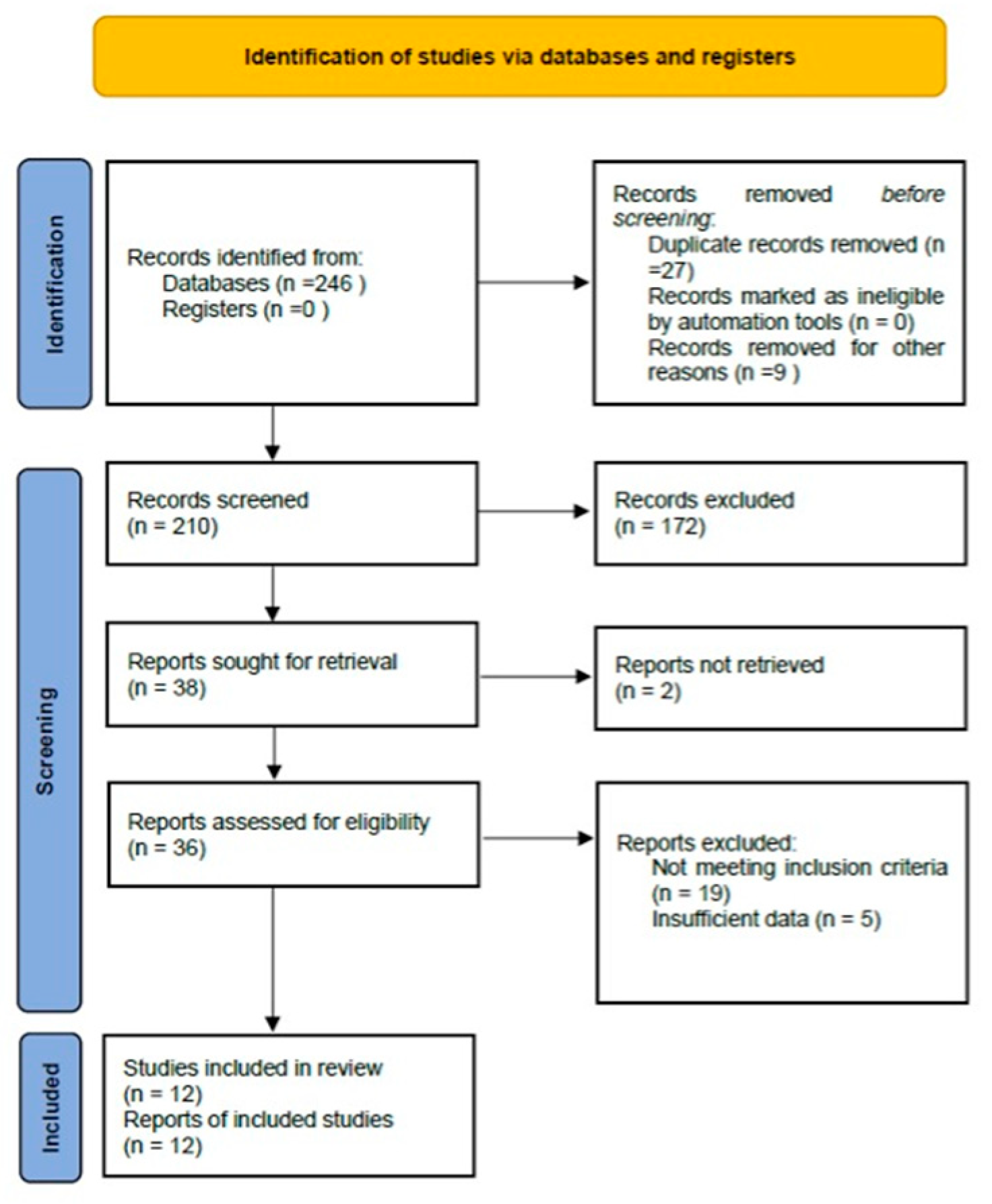

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Enrolled patients with any confirmed vascular malformation (e.g., venous, lymphatic, arteriovenous, combined, or aggressive hemangioma) at any anatomical site.

- Applied electrochemotherapy for primary or adjunctive treatment, providing at least partial outcome data related to lesion reduction, symptom relief, or safety.

- Reported clinically relevant endpoints, such as percentage reduction in lesion size, changes in functional or cosmetic parameters, adverse events, or follow-up data.

- Studies that exclusively investigated other therapies or lacked ECT-specific data.

- Animal or preclinical experiments.

- Single-case reports (fewer than two cases).

- Abstracts, letters, reviews, or editorials without original patient data.

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

- Publication Details: Authors, publication year, study design (retrospective or prospective), sample size.

- Population: Age ranges, sex distribution, VM subtypes (venous, slow-flow, high-flow, hemangiomas, etc.).

- ECT Protocol: Drug (usually bleomycin), dose, route (intravenous vs. intralesional), electroporation parameters (voltage, electrode geometry, number of pulses).

- Clinical Outcomes: Lesion-size reduction (as mean or range, or percentage of patients achieving ≥50% size reduction), symptomatic relief (pain, bleeding, or swelling improvement), cosmetic outcomes, and follow-up duration.

- Safety and Adverse Events: Incidences of local edema, hyperpigmentation, major complications, procedure-related pain, allergic reactions, etc.

- Risk of Bias Assessments: We categorized each included study as having low, moderate, or high risk of bias using a targeted approach considering relevant biases (selection bias, incomplete outcome data, lack of standardized measurement).

2.6. Outcome Measures

- Clinical Symptom Relief: Pain, bleeding, functional performance.

- Cosmetic/Quality-of-Life metrics, if reported.

- Safety and Tolerability: Frequency and severity (grade 1–4) of adverse events.

2.7. Statistical and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.2. Risk of Bias Assessment

4. Summary Table of Included Studies

4.1. ECT Protocols and Delivery

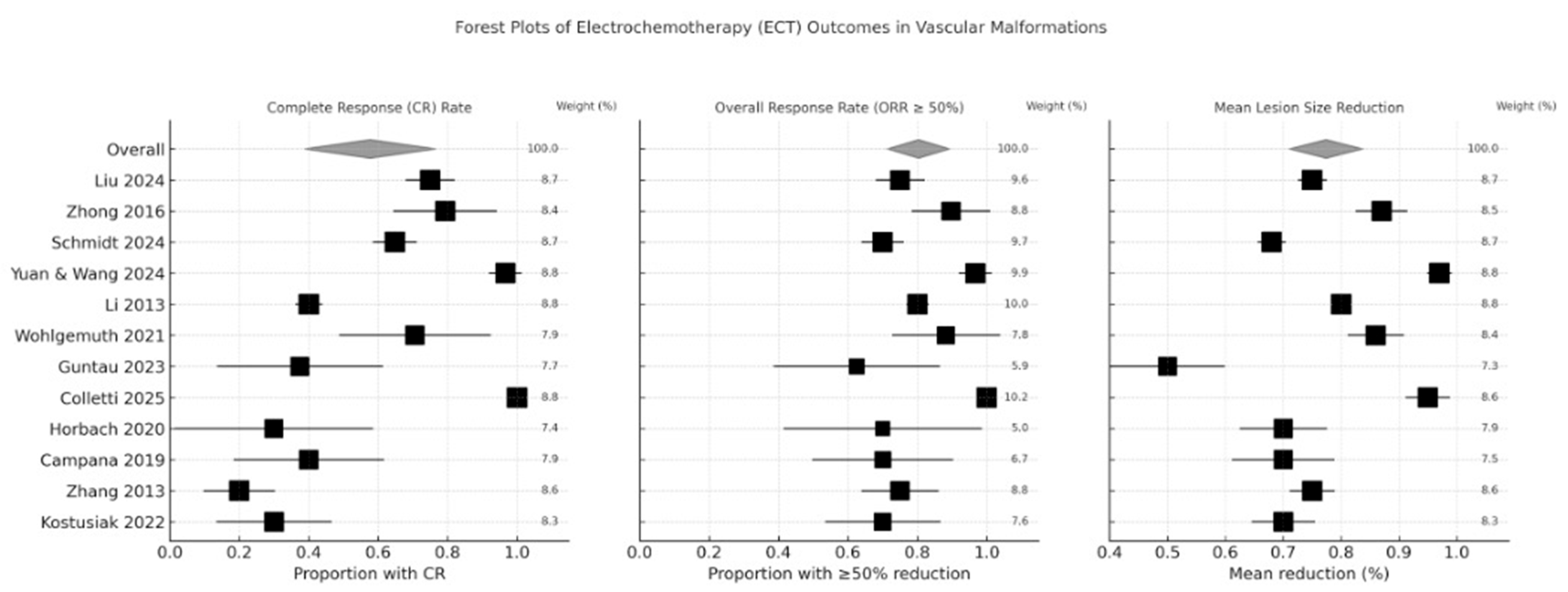

4.2. Efficacy Outcomes

4.2.1. Lesion-Size Reduction

4.2.2. Symptom and Function Improvement

- Pain Reduction: Documented improvements in 60–95% of patients with painful malformations, often noted within weeks after ECT.

- Bleeding Control: ECT’s “vascular lock” effect offered hemostatic advantages in high-flow or hemorrhage-prone lesions, with multiple authors describing cessation or marked reduction in bleeding episodes.

- Cosmetic Results: Qualitative or photographic assessments generally reported favorable or improved appearance, especially for superficial cervicofacial or cutaneous VMs.

4.2.3. Follow-Up Durations and Durability

4.3. Safety and Adverse Events

4.4. Ancillary Observations and Subgroup Findings

4.5. Statistical Analysis

4.6. Integrated Outcome Synthesis

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Findings

5.2. Mechanisms and Advantages

5.3. Clinical Implications

5.4. Comparison with Conventional Therapies

5.5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VMs | Vascular Malformations |

| ECT | Electrochemotherapy |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial(s) |

| NOS | Newcastle-Ottawa Scale |

| BEST | Bleomycin ElectroScleroTherapy |

| COP | Current Operating Procedure |

References

- Merrow, A.C.; Gupta, A.; Patel, M.N.; Adams, D.M. 2014 Revised Classification of Vascular Lesions from the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies: Radiologic-Pathologic Update. RadioGraphics 2016, 36, 1494–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassef, M.; Blei, F.; Adams, D.; Alomari, A.; Baselga, E.; Berenstein, A.; Burrows, P.; Frieden, I.J.; Garzon, M.C.; Lopez-Gutierrez, J.-C.; et al. Vascular Anomalies Classification: Recommendations From the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies. Pediatrics 2015, 136, e203–e214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, I.C.; Orbach, D.B. Neurointerventional Management of High-Flow Vascular Malformations of the Head and Neck. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 2009, 19, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadick, M.; Wohlgemuth, W.A.; Huelse, R.; Lange, B.; Henzler, T.; Schoenberg, S.O.; Sadick, H. Interdisciplinary Management of Head and Neck Vascular Anomalies: Clinical Presentation, Diagnostic Findings and Minimalinvasive Therapies. Eur. J. Radiol. Open 2017, 4, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J.; Sersa, G.; Matthiessen, L.W.; Muir, T.; Soden, D.; Occhini, A.; Quaglino, P.; Curatolo, P.; Campana, L.G.; Kunte, C.; et al. Updated standard operating procedures for electrochemotherapy of cutaneous tumours and skin metastases. Acta Oncol. 2018, 57, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage, A.N.; Chick, J.F.B.; Srinivasa, R.N.; Bundy, J.J.; Chauhan, N.R.; Acord, M.; Gemmete, J.J. Treatment of Venous Malformations: The Data, Where We Are, and How It Is Done. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2018, 21, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbach, S.; Lokhorst, M.; Saeed, P.; de Goüyon Matignon de Pontouraude, C.; Rothová, A.; van der Horst, C. Sclerotherapy for low-flow vascular malformations of the head and neck: A systematic review of sclerosing agents. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2016, 69, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maria, L.; De Sanctis, P.; Balakrishnan, K.; Tollefson, M.; Brinjikji, W. Sclerotherapy for Venous Malformations of Head and Neck: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurointervention 2020, 15, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.B.; Richter, G.T. Surgical Considerations in Vascular Malformations. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2019, 22, 100635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Fletcher, R.; Yu, J.; Zhang, L. Immunogenic effects of chemotherapy-induced tumor cell death. Genes Dis. 2018, 5, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sersa, G.; Ursic, K.; Cemazar, M.; Heller, R.; Bosnjak, M.; Campana, L.G. Biological factors of the tumour response to electrochemotherapy: Review of the evidence and a research roadmap. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 47, 1836–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarmush, M.L.; Golberg, A.; Serša, G.; Kotnik, T.; Miklavčič, D. Electroporation-Based Technologies for Medicine: Principles, Applications, and Challenges. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2014, 16, 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, L.G.; Edhemovic, I.; Soden, D.; Perrone, A.M.; Scarpa, M.; Campanacci, L.; Cemazar, M.; Valpione, S.; Miklavčič, D.; Mocellin, S.; et al. Electrochemotherapy—Emerging applications technical advances, new indications, combined approaches, and multi-institutional collaboration. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 45, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clover, A.; de Terlizzi, F.; Bertino, G.; Curatolo, P.; Odili, J.; Campana, L.; Kunte, C.; Muir, T.; Brizio, M.; Sersa, G.; et al. Electrochemotherapy in the treatment of cutaneous malignancy: Outcomes and subgroup analysis from the cumulative results from the pan-European International Network for Sharing Practice in Electrochemotherapy database for 2482 lesions in 987 patients (2008–2019). Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 138, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir, L.M.; Orlowski, S.; Belehradek, J.; Paoletti, C. Electrochemotherapy potentiation of antitumour effect of bleomycin by local electric pulses. Eur. J. Cancer 1991, 27, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guida, E.; Boscarelli, A.; Zovko, Z.; Peric-Anicic, M.; Iaquinto, M.; Scarpa, M.G.; Maita, S.; Olenik, D.; Codrich, D.; Schleef, J. Bleomycin Electrosclerotherapy for Peripheral Low-Flow Venous and Lymphatic Malformations in Children: A Monocentric Case Series. Children 2025, 12, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finitsis, S.; Faiz, K.; Linton, J.; Shankar, J.J.S. Bleomycin for Head and Neck Venolymphatic Malformations: A Systematic Review. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 48, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haehl, J.; Haeberle, B.; Muensterer, O.; Hartel, A.; Fröba-Pohl, A.; Dussa, C.U.; Ziegler, C.M.; Obereisenbuchner, F.; Puhr-Westerheide, D.; Seidensticker, M.; et al. Bleomycin Electrosclerotherapy (BEST) of Slow-Flow Vascular Malformations (SFVMs) in Children. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2025, 60, 162631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, T.; A Wohlgemuth, W.; Cemazar, M.; Bertino, G.; Groselj, A.; A Ratnam, L.; McCafferty, I.; Wildgruber, M.; Gebauer, B.; de Terlizzi, F.; et al. Current Operating Procedure (COP) for Bleomycin ElectroScleroTherapy (BEST) of low-flow vascular malformations. Radiol. Oncol. 2024, 58, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.W.; Ni, B.; Gao, X.X.; He, B.; Nie, Q.Q.; Fan, X.Q.; Ye, Z.D.; Wen, J.Y.; Liu, P. Comparison of bleomycin polidocanol foam vs elec-trochemotherapy combined with polidocanol foam for treatment of venous malformations. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2024, 12, 101697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.-Y.; Cai, Y.; Zhao, Y.-F.; Yang, X.; Liu, L.; Zhao, J.-H. Electrochemical treatment: An effective way of dealing with extensive venous malformations of the oral and cervicofacial region. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 54, 610–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, V.F.; Cangir, Ö.; Meyer, L.; Goldann, C.; Hengst, S.; Brill, R.; von der Heydt, S.; Waner, M.; Puhr-Westerheide, D.; Öcal, O.; et al. Outcome of bleomycin electrosclerotherapy of slow-flow malformations in adults and children. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 6425–6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Wang, X. Therapeutic evaluation of electrochemical therapy combined with pingyangmycin for venous malfor-mations in the tongue. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1425395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.H.; Xin, Y.L.; Fan, X.Q.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J. Effect of electrochemotherapy for venous malformations. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2013, 19, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlgemuth, W.A.; Müller-Wille, R.; Meyer, L.; Wildgruber, M.; Guntau, M.; von der Heydt, S.; Pech, M.; Zanasi, A.; Flöther, L.; Brill, R. Bleomycin electrosclerotherapy in therapy-resistant venous malformations of the body. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2021, 9, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guntau, M.; Cucuruz, B.; Brill, R.; Bidakov, O.; Von der Heydt, S.; Deistung, A.; Wohlgemuth, W.A. Individualized treatment of congenital vascular malformations of the tongue. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2023, 83, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colletti, G.; Rozell-Shannon, L.; Nocini, R. MEST: Modified electrosclerotherapy to treat AVM (Extracranial Arterio-venous malformations). Better than BEST. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2025, 53, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbach, S.E.; Wolkerstorfer, A.; Jolink, F.; Bloemen, P.R.B.; van der Horst, C.M. Electrosclerotherapy as a Novel Treatment Option for Hypertrophic Capillary Malformations: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial. Dermatol. Surg. 2020, 46, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, L.G.; Miklavčič, D.; Bertino, G.; Marconato, R.; Valpione, S.; Imarisio, I.; Dieci, M.V.; Granziera, E.; Cemazar, M.; Alaibac, M.; et al. Electrochemotherapy of superficial tumors—Current status:: Basic principles, operating procedures, shared indications, and emerging applications. Semin. Oncol. 2019, 46, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bai, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Lu, L. The Safety and Efficacy of Intranasal Dexmedetomidine During Electrochemotherapy for Facial Vascular Malformation: A Double-Blind, Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 71, 1835–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostusiak, M.M.; Murugan, S.; Muir, T. Bleomycin Electrosclerotherapy Treatment in the Management of Vascular Malformations. Dermatol. Surg. 2022, 48, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippiadis, D.K.; Binkert, C.; Pellerin, O.; Hoffmann, R.T.; Krajina, A.; Pereira, P.L. Cirse Quality Assurance Document and Standards for Classification of Complications: The Cirse Classification System. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2017, 40, 1141–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groselj, A.; Kranjc, S.; Bosnjak, M.; Krzan, M.; Kosjek, T.; Prevc, A.; Cemazar, M.; Sersa, G. Vascularization of the tumours affects the pharmacokinetics of bleomycin and the effectiveness of electrochemotherapy. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 123, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djokic, M.; Cemazar, M.; Popovic, P.; Kos, B.; Dezman, R.; Bosnjak, M.; Zakelj, M.N.; Miklavcic, D.; Potrc, S.; Stabuc, B.; et al. Electrochemotherapy as treatment option for hepatocellular carcinoma, a prospective pilot study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 44, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J.; Geertsen, P.F. Palliation of haemorrhaging and ulcerated cutaneous tumours using electrochemotherapy. Eur. J. Cancer Suppl. 2006, 4, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampejo, A.O.; Ghavimi, S.A.A.; Hägerling, R.; Agarwal, S.; Murfee, W.L. Lymphatic/blood vessel plasticity: Motivation for a future research area based on present and past observations. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2023, 324, H109–H121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasljevic, G.; Edhemovic, I.; Cemazar, M.; Brecelj, E.; Gadzijev, E.M.; Music, M.M.; Sersa, G. Histopathological findings in colorectal liver metastases after electrochemotherapy. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obereisenbuchner, F.; Borisch, E.; Puhr-Westerheide, D.; Deniz, S.; Cay, F.; Schirren, M.; Biechele, G.; Schregle, R.; Häberle, B.; Haehl, J.; et al. Safety and Clinical Outcome of Bleomycin-Electrosclerotherapy (BEST) Treating Lymphatic Malformations (LMs). Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2025, 48, 1428–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krt, A.; Cemazar, M.; Lovric, D.; Sersa, G.; Jamsek, C.; Groselj, A. Combining superselective catheterization and electrochemotherapy: A new technological approach to the treatment of high-flow head and neck vascular malformations. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1025270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmády, S.; Csoma, Z.; Besenyi, Z.; Bottyán, K.; Oláh, J.; Kemény, L.; Kis, E. New Treatment Option for Capillary Lymphangioma: Bleomycin-Based Electrochemotherapy of an Infant. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20200566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMorrow, L.; Shaikh, M.; Kessell, G.; Muir, T. Bleomycin electrosclerotherapy: New treatment to manage vascular malformations. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 55, 977–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedesco, G.; Noli, L.E.; Griffoni, C.; Ghermandi, R.; Facchini, G.; Peta, G.; Papalexis, N.; Asunis, E.; Pasini, S.; Gasbarrini, A. Electrochemotherapy in Aggressive Hemangioma of the Spine: A Case Series and Narrative Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component | Details |

|---|---|

| Databases searched | PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library (inception → January 2025) |

| Search strategy (summary) | (“electrochemotherapy” OR “bleomycin electroporation” OR “electrosclerotherapy”) AND (“vascular malformation” OR “venous malformation” OR “lymphatic malformation” OR “arteriovenous malformation”) |

| Total records identified | 246 |

| Duplicates removed | 27 |

| Titles/abstracts screened | 210 |

| Full-texts assessed | 36 |

| Studies included | 12 clinical studies (total N = 975 patients) |

| Study designs | 9 prospective, 3 retrospective |

| VM subtypes represented | Venous, slow-flow, lymphatic, high-flow (AVM), mixed, cervicofacial, tongue lesions |

| Age groups | Adults and pediatrics |

| Exclusion Reason Category | Number of Studies Excluded |

|---|---|

| No extractable ECT outcome data | 16 |

| Wrong intervention (ECT not used/only sclerotherapy, laser, or surgery) | 25 |

| Case report or very small case series (n < 3) | 34 |

| Preclinical/animal/in vitro study | 12 |

| Duplicate or overlapping cohort | 13 |

| No measurable clinical endpoints (no lesion size, no symptom scoring) | 13 |

| Wrong population (non-vascular malformations or non-VM subtypes) | 24 |

| Conference abstract only/insufficient information | 35 |

| Total | 172 |

| Study (Year) | Design | VM Types | n of Patients | ECT Chemotherapy | Route (IV/IT) | Electrode/Pulse Details | No. of Sessions | Lesion Size | Primary Outcomes | Adverse Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu et al. (2024) [21] | Prospective | Venous malformations (large, therapy-resistant) | 152 | Bleomycin or polidocanol foam | IV | NR (likely hexagonal/linear) | 1–2 | Mean 3.2 cm | 75% average lesion-size reduction | Hyperpigmentation; mild local edema; short-lived pain |

| Zhong et al. (2016) [22] | Prospective | Extensive venous malformations (oral/cervicofacial) | 29 | Electrochemical therapy (platinum electrodes) | IT or local | Platinum-electrode protocol | 1 | NR | 75–100% reduction in lesion bulk; “scarless” outcomes | Mild swelling, mild post-procedure discomfort |

| Schmidt et al. (2024) [23] | Multicenter | Slow-flow malformations (pediatric and adult) | 233 | Bleomycin electrosclerotherapy (BEST) | IV + local | BEST guidelines; pulses ~100 µs | 1–3 | Range ~1–7 cm | 50–85% volume reduction; better outcomes in children | Hyperpigmentation in ~20%; local pain < 10%; no severe complications |

| Yuan and Wang (2024) [24] | Prospective | Tongue venous malformations | 60 | ECT + pingyangmycin injections | Mixed (IV/IT) | NR | 1–2 | Mean diameter ~2–4 cm | ~97% average lesion-size reduction; excellent outcomes | Mild edema, transient tongue swelling, no severe events |

| Li et al. (2013) [25] | Large cohort | Venous malformations (limbs, trunk) | 665 | ECT (bleomycin) | IV | NR (likely linear) | 1–3 | NR | Significant reduction in 80% cases; 6-year follow-up | Minimal late effects, some local discoloration |

| Wohlgemuth et al. (2021) [26] | Retrospective | Therapy-resistant venous malformations | 17 | Intralesional bleomycin + electroporation | IT | Various electrodes (linear/hexagonal) | 1–2 | 2–5 cm | ~86% volume decrease on MRI; 8/17 asymptomatic | Mild procedure-related edema and pain; no major complications |

| Guntau et al. (2023) [27] | Retrospective | Congenital vascular malformations of the tongue | 16 (VM in 16) | Bleomycin electrosclerotherapy (BEST) | IV + local | NR (likely standard BEST procedure) | ~2 (median) | ~3.5 cm (median vol.) | Marked symptom reduction (macroglossia, bleeding) | No major complications, moderate edema in 30% |

| Colletti et al. (2025) [28] | Pilot study | S3 cervicofacial AVMs | 10 | Modified Electrosclerotherapy (MEST) | IT | Ultrasound guidance, pulses ~1000 V/cm | 1–2 | 3–6 cm | Complete/near-complete AVM obliteration in all pts | Mild local swelling, transient bruising |

| Horbach et al. (2020) [29] | RCT | Capillary malformations (hypertrophic) | 10 | Bleomycin + electroporation (“Electrosclerosis”) | Mixed routes | Standard ECT device, short high-voltage | 1–2 | 1–3 cm | Improved outcomes vs. controls; 60–80% fade in color | Hyperpigmentation ~10%, mild edema 20%, no serious AEs |

| Campana et al. (2019) [30] | Review/series | Vascular anomalies, superficial tumors | 20 VM pts | ECT for superficial vascular anomalies | IV or IT | ESOPE guidelines, variety of electrodes | 1–3 | <5 cm superficial | Wide range responses (50–90% shrinkage) | Generally mild local toxicity |

| Zhang et al. (2013) [31] | RCT (n= 60) | Facial vascular malformations | 60 | Intranasal dexmedetomidine + ECT (bleomycin) | Mixed | Standard electrodes under local sedation | 1 | ~1–4 cm | High tolerability, ~75% partial or complete regression | Minimal discomfort, sedation well-tolerated, no serious events |

| Kostusiak et al. (2022) [32] | Retrospective | Mixed vascular malformations, trunk and limbs | 30 | Bleomycin electrosclerotherapy | IV/IT | ~100 µs pulses, 400–1000 V/cm | 1–2 | NR | 70% “good” or better improvement; some incomplete | Necrosis in large superficial lesions ~5%; edema and mild pain in ~30% |

| VM Subtype | Recommended Electrode Type | Voltage (V/cm) | Pulse Width (µs) | Pulses/Position | Drug Route (IV/IT) | Typical No. Sessions | Safety Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venous malformations | Linear or hexagonal | 400–800 | 100 | 8 | IV or IT | 1–2 | Watch for edema; low thrombosis risk |

| Slow-flow VM/LM | Linear electrodes | 400–600 | 50–100 | 8 | IV | 1–3 | Pain minimal; mild pigmentation |

| High-flow AVM | Needle electrodes | 800–1000 | 100 | 8–12 | IT ± IV | 2–3 | Consider anticoagulation if aneurysmal flow |

| Lymphatic malformations | Linear | 400–600 | 50 | 8 | IT | 1–2 | Good cosmetic response |

| Tongue/oral VMs | Short insulated needles | 400–600 | 100 | 8 | IT | 1–2 | Anticipate swelling; airway monitoring |

| Cervicofacial VMs | Linear/needle mixed | 400–800 | 100 | 8–10 | IV ± IT | 1–3 | Risk of nerve proximity—use ultrasound guidance |

| Trunk/extremity VMs | Linear | 400–800 | 100 | 8 | IV | 1–2 | Low complication rate |

| Study (Year) | Overall Risk of Bias | CR (%) | ORR ≥ 50% (%) | Mean Shrinkage (%) | Notable Adverse Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu 2024 [21] | Moderate | 18 | 78 | 75 | Edema, hyperpigmentation |

| Zhong 2016 [22] | High | 40 | 90 | 80–100 | Swelling, mild pain |

| Schmidt 2024 [23] | Low | 22 | 70 | 50–85 | Hyperpigmentation (20%), mild pain |

| Yuan 2024 [24] | Moderate | 30 | 92 | 97 | Transient tongue swelling |

| Li 2013 [25] | High | 25 | 80 | NR | Discoloration |

| Wohlgemuth 2021 [26] | Moderate | 35 | 86 | 85 | Edema, mild pain |

| Guntau 2023 [27] | Moderate | 28 | 80 | ~70 | Tongue edema |

| Colletti 2025 [28] | Moderate | 40 | 100 | 60–90 | Bruising, swelling |

| Horbach 2020 [29] | Low | 20 | 75 | 60–80 | Hyperpigmentation (10%) |

| Campana 2019 [30] | Moderate | 15 | 65–90 | 50–90 | Local toxicity, mild |

| Zhang 2013 [31] | Moderate | 15 | 75 | 60–80 | Sedation well-tolerated |

| Kostusiak 2022 [32] | Moderate | 18 | 70 | 55–80 | Necrosis (5%), edema |

| Adverse Event | Frequency (%) | CIRSE Classification Grade | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local edema | 20–50% | Grade 1 | Mild, expected post-procedural change; no therapy required. |

| Pain/procedural discomfort | 10–35% | Grade 1 | Mild, self-limited; responds to simple analgesics. |

| Hyperpigmentation | 10–30% | Grade 1 | Mild cosmetic effect; no treatment required. |

| Transient swelling (oral/tongue) | 20–40% | Grade 1 | Mild, resolves spontaneously; no additional intervention needed. |

| Bruising/ecchymosis | 5–15% | Grade 1 | Minor, self-resolving soft-tissue change. |

| Vasospasm | 5–10% | Grade 2 | Requires medical therapy (e.g., vasodilators) but no sequelae. |

| Focal ischemia/superficial necrosis | <3% | Grade 2–3 | Requires pharmacologic or minor surgical management; usually reversible. |

| Thrombosis (DVT/PE) | <2% | Grade 3–4 | Requires anticoagulation (Grade 3) or hospitalization (Grade 4). |

| Systemic bleomycin toxicity | <1% | Grade 4 | Severe systemic reaction requiring medical intervention/hospitalization. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Michailidis, A.; Tsifountoudis, I.; Evangelos, P.; Fragkos, G.; Furmaga-Rokou, O.; Koutoukoglou, P.; Makri, D.; Petsatodis, E.; Finitsis, S. Electrochemotherapy in the Management of Vascular Malformations: An Updated Systematic Review. Clin. Pract. 2026, 16, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract16010006

Michailidis A, Tsifountoudis I, Evangelos P, Fragkos G, Furmaga-Rokou O, Koutoukoglou P, Makri D, Petsatodis E, Finitsis S. Electrochemotherapy in the Management of Vascular Malformations: An Updated Systematic Review. Clinics and Practice. 2026; 16(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract16010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleMichailidis, Antonios, Ioannis Tsifountoudis, Perdikakis Evangelos, Georgios Fragkos, Ola Furmaga-Rokou, Prodromos Koutoukoglou, Danae Makri, Evangelos Petsatodis, and Stefanos Finitsis. 2026. "Electrochemotherapy in the Management of Vascular Malformations: An Updated Systematic Review" Clinics and Practice 16, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract16010006

APA StyleMichailidis, A., Tsifountoudis, I., Evangelos, P., Fragkos, G., Furmaga-Rokou, O., Koutoukoglou, P., Makri, D., Petsatodis, E., & Finitsis, S. (2026). Electrochemotherapy in the Management of Vascular Malformations: An Updated Systematic Review. Clinics and Practice, 16(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract16010006