Patterns of Ocular Involvement and Associated Factors in Adult Measles: A Retrospective Study from a Romanian Tertiary Hospital

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Variables and Definitions

2.4. Data Sources

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethics Approval

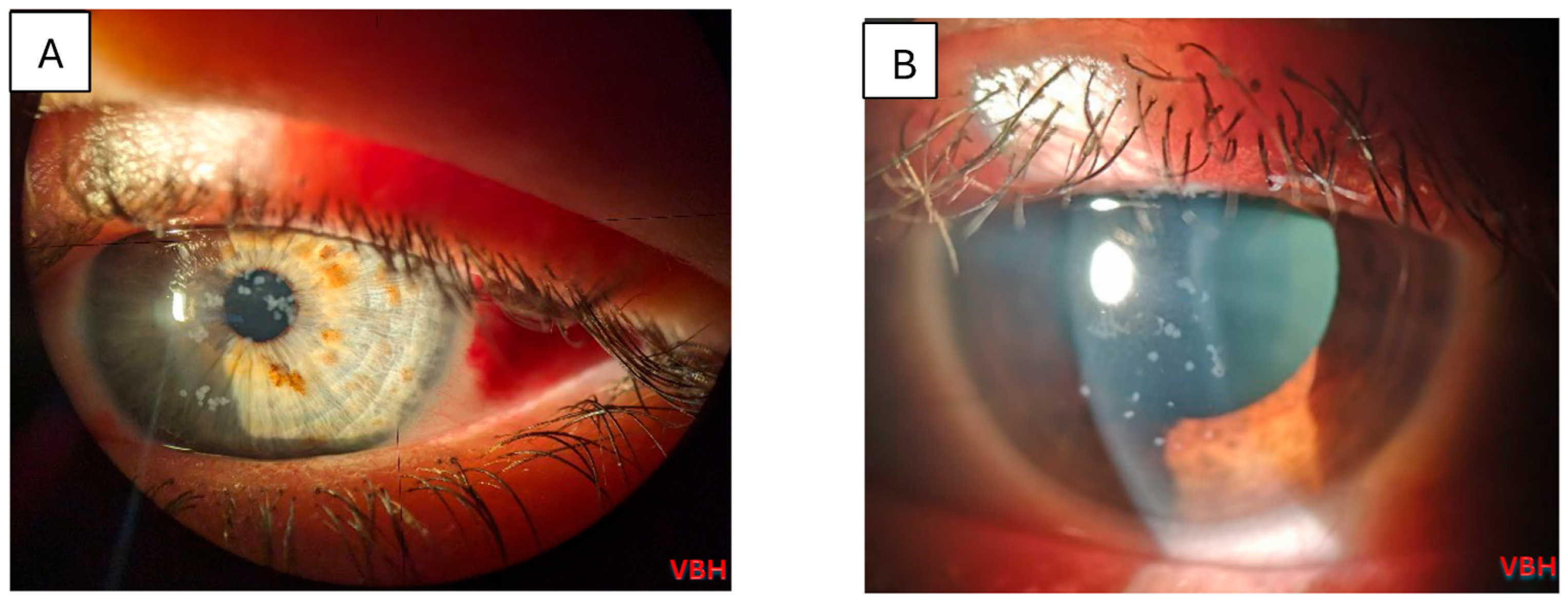

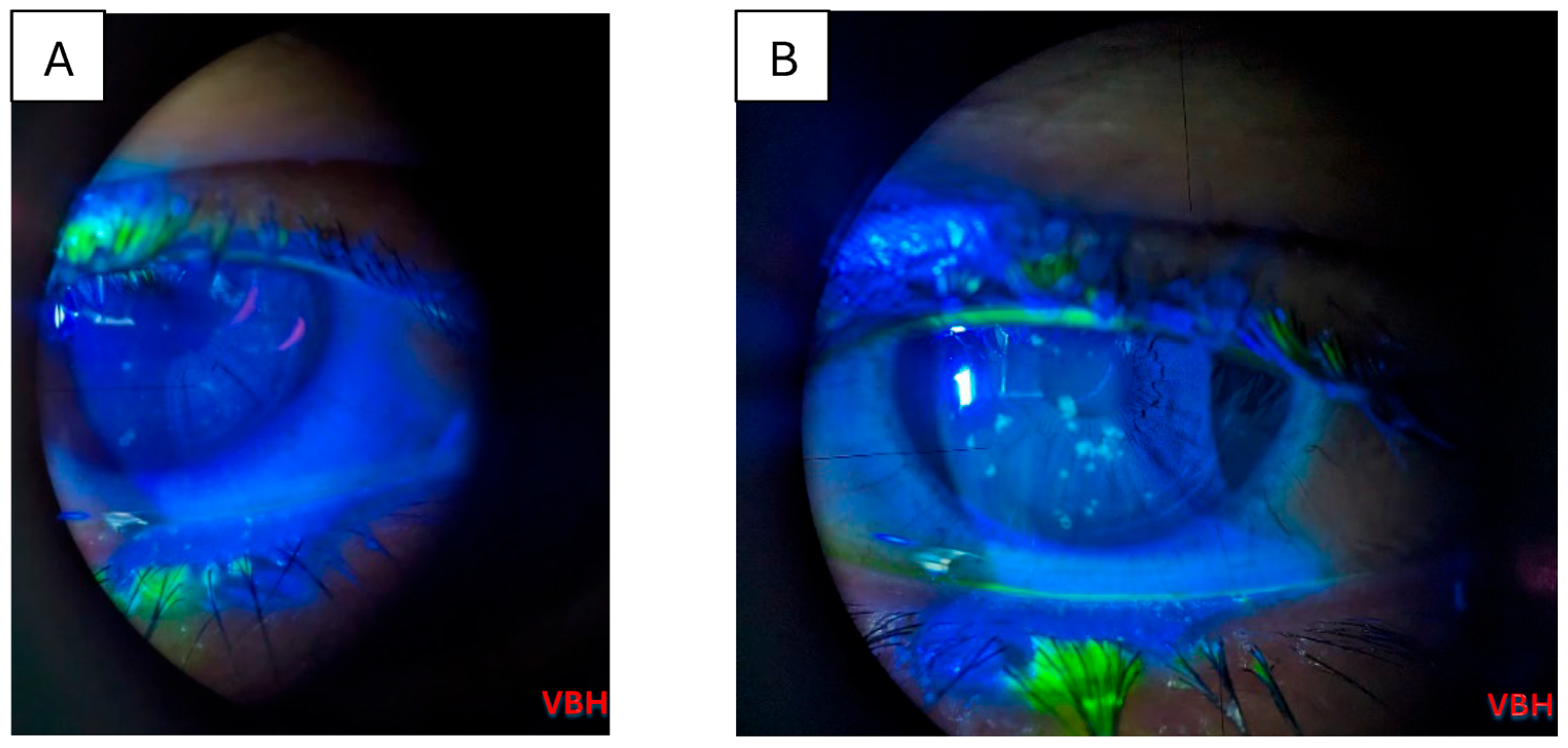

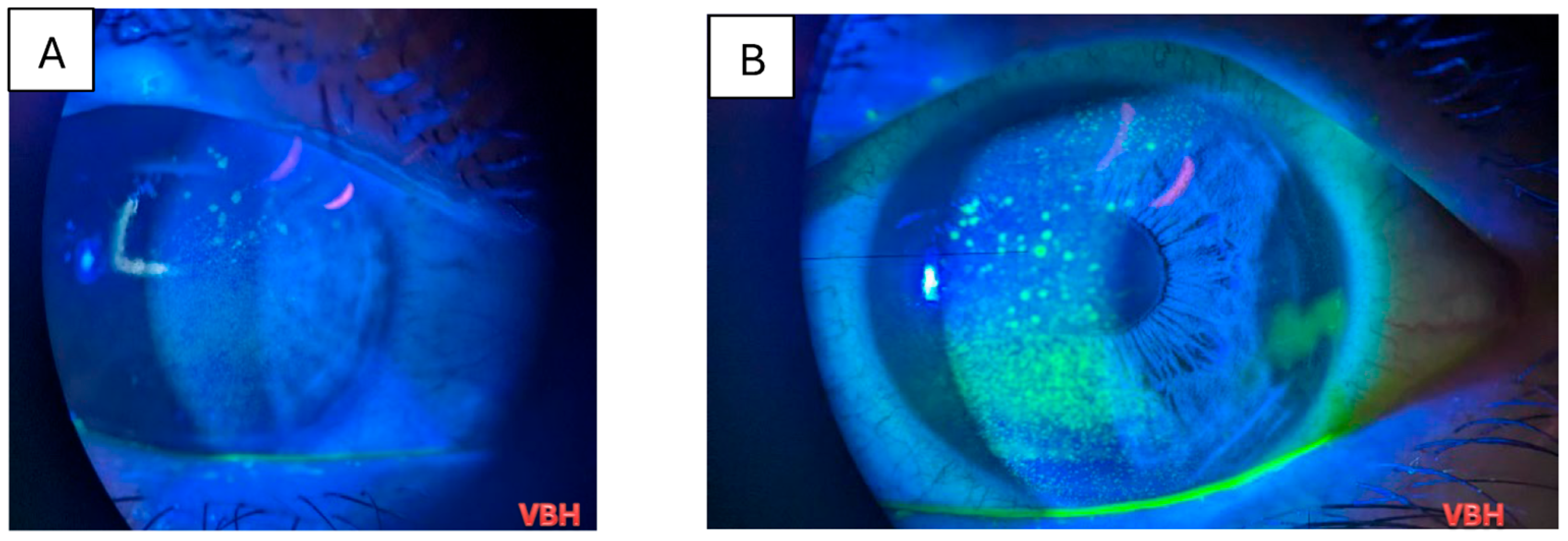

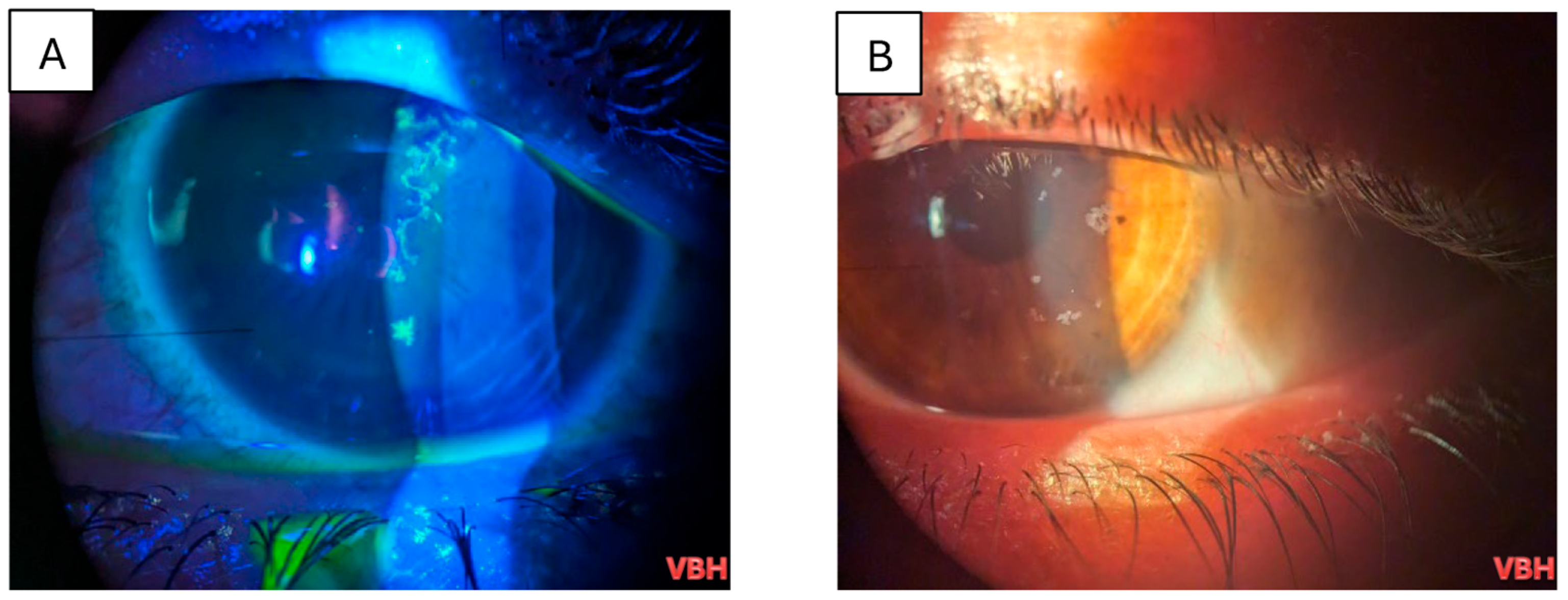

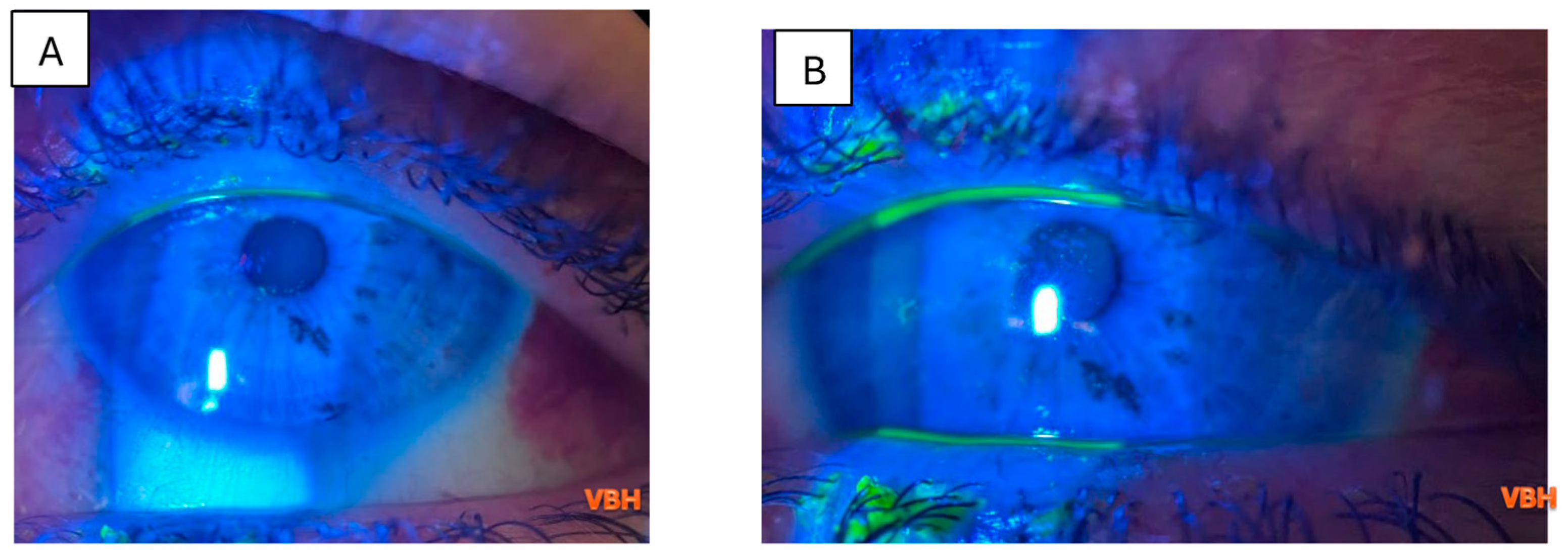

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALT | Alanine transaminaze |

| AST | Aspartate transaminase |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| NLR | Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| R0 | Basic reproduction number |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Moss, W.J. Measles. Lancet 2017, 390, 2490–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, F.M.; Bolotin, S.; Lim, G.; Heffernan, J.; Deeks, S.L.; Li, Y.; Crowcroft, N.S. The basic reproduction number (R0) of measles: A systematic review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, e420–e428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parums, D.V. A Review of the Resurgence of Measles, a Vaccine-Preventable Disease, as Current Concerns Contrast with Past Hopes for Measles Elimination. Med. Sci. Monit. 2024, 30, e944436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Measles—Fact Sheet. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Medscape. Measles Clinical Presentation. 2025. Available online: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/966220-clinical (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Merck Manual Professional Edition. Measles. 2025. Available online: https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/common-viral-infections-in-infants-and-children/measles (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Rota, P.A.; Moss, W.J.; Takeda, M.; de Swart, R.L.; Thompson, K.M.; Goodson, J.L. Measles. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, R.T.; Halsey, N.A. The clinical significance of measles: A review. J. Infect. Dis. 2004, 189, S4–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laksono, B.M.; de Vries, R.D.; McQuaid, S.; Duprex, W.P.; de Swart, R.L. Measles Virus Host Invasion and Pathogenesis. Viruses 2016, 8, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). History of Measles. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/measles/about/history.html (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases: The Pink Book. Chapter 13—Measles. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/pinkbook/hcp/table-of-contents/chapter-13-measles.html (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Measles Vaccines: WHO Position Paper—April 2017. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 2017, 92, 205–227. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-wer9217-205-227 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Lazar, M.; Stănescu, A.; Penedos, A.R.; Pistol, A. Characterisation of measles after the introduction of the combined measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine in 2004 with focus on the laboratory data, 2016 to 2019 outbreak, Romania. Euro Surveill. 2019, 24, 1900041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- ECDC. Communicable Disease Threats Report, Week 34 (16–22 August 2020); European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/communicable-disease-threats-report-22-aug-2020.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Ministerul Sănătății. Ordin nr. 4128/2023 Privind Declararea Epidemiei de Rujeolă. 2023. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/276996 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- UNICEF România. Press Release: Regiunea Europeană Raportează cel Mai Mare Număr de Cazuri de Rujeolă din Ultimii 25 de Ani—UNICEF, OMS/Europa. 2025. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/romania/ro/comunicate-de-presă/regiunea-europeană-raportează-cel-mai-mare-număr-de-cazuri-de-rujeolă-din (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe (WHO Europe). Measles and Rubella Surveillance Data: Epidemiological Update for the WHO European Region, 2023–2024; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024; Available online: https://immunizationdata.who.int/dashboard/regions/european-region (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Stanescu, A.; Ruta, S.M.; Cernescu, C.; Pistol, A. Suboptimal MMR Vaccination Coverages—A Constant Challenge for Measles Elimination in Romania. Vaccines 2024, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. Measles Immunization Coverage (% of Children Ages 12–23 Months). Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/39728 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Issam Eddine, E.; Sana, S.; Achraf, F.; Chiraz, A.; Walid, Z. Ocular manifestations of measles in adults: About three cases. J. Fr. Ophtalmol. 2020, 43, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, A.P.C.; Watson, A.; Subbiah, S. Rubeola keratitis emergence during a recent measles outbreak in New Zealand. J. Prim. Health Care 2020, 12, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bîrluțiu, V.; Bîrluțiu, R.-M. Measles—Clinical and Biological Manifestations in Adult Patients, Including a Focus on the Hepatic Involvement. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| N, % | 250 (100%) |

| Sex (Female) (Nr., %) | 131 (52.4%) |

| Age (Mean ± SD, Median (IQR)) | 33.32 ± 10.65, 33 (23–43) |

| Workplace domain (Nr., %) (N = 239) | |

| Healthcare | 26 (10.9%) |

| Other | 213 (89.1%) |

| Environment (Urban) (Nr., %) | 150 (60%) |

| Education (Nr., %) (N = 198) | |

| Primary | 22 (11.1%) |

| Secondary | 105 (53%) |

| Academic | 39 (19.7%) |

| No education | 32 (16.2%) |

| Travel in the past 14 days (Nr., %) (N = 249) | 2 (0.8%) |

| Antibiotic treatment in the past 14 days (Nr., %) | 74 (29.6%) |

| Health insurance (Nr., %) | 182 (72.8%) |

| Medical history—Measles (Nr., %) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Symptoms | |

| Days—Onset—Admission (Mean ± SD, Median (IQR)) (N = 249) | 4.72 ± 1.69, 5 (4–6) |

| Fever (Nr., %) | 242 (96.8%) |

| Exanthema (Nr., %) | 250 (100%) |

| Koplik sign (Nr., %) | 160 (64%) |

| Days—Exanthema—Admission (Mean ± SD, Median (IQR)) (N = 243) | 1.76 ± 1.61, 2 (1–3) |

| Complications (Nr., %) | |

| Pneumonia | 216 (86.4%) |

| Respiratory failure | 41 (16.4%) |

| Encephalitis | 1 (0.4%) |

| Hospitalization period (Mean ± SD, Median (IQR)) | 4.57 ± 1.72, 4 (4–6) |

| Laboratory parameters (Mean ± SD, Median (IQR)) | |

| Neutrophils (cells/μL) | 4649.6 ± 1942.55 4400 (3300–5625) |

| Lymphocytes (cells/μL) | 640 ± 466.12 500 (400–800) |

| NLR | 9.857 ± 7.588 8 (5.5–11.4) |

| AST (UI/mL) (N = 241) | 164.26 ± 167.7 107 (59–222) |

| ALT (UI/mL) (N = 249) | 225.69 ± 232.42 144 (64–300.5) |

| ALT/AST (N = 241) | 1.44 ± 0.837 1.313 (0.941–1.678) |

| Antibiotic treatment (Nr., %) | 164 (65.6%) |

| Eye exam (Nr., %) | |

| Ophthalmologic examination performed | 88 (35.2%) |

| Ocular lesions (N = 88) | 82 (93.2%) |

| Type of lesions (N = 82) | |

| Keratitis | 53 (64.6%) |

| Other | 29 (35.4%) |

| Parameter/Ocular Lesions (N = 88) | Absent (N = 6) | Present (N = 82) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (Female) (Nr., %) | 3 (50%) | 38 (46.3%) | 1.000 ‡ |

| Age (Median (IQR)) | 35 (22–41.25) | 34 (24–44) | 0.759 § |

| Environment (Urban) (Nr., %) | 3 (50%) | 51 (62.2%) | 0.673 ‡ |

| Education (Nr., %) (N = 69) | |||

| Primary (N = 7) | 0 (0%) | 7 (10.8%) | 0.525 ‡ |

| Secondary (N = 36) | 4 (100%) | 32 (49.2%) | |

| Academic (N = 19) | 0 (0%) | 19 (29.2%) | |

| No education (N = 7) | 0 (0%) | 7 (10.8%) | |

| History—Travel (Nr., %) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| History—Antibiotic treatment (Nr., %) | 2 (33.3%) | 23 (28%) | 1.000 ‡ |

| Health insurance (Nr., %) | 4 (66.7%) | 65 (79.3%) | 0.606 ‡ |

| Medical history—Measles (Nr., %) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Symptoms | |||

| Days—Onset—Admission (Median (IQR)) (N = 87) | 5 (3.25–7) | 5 (4–6) | 0.726 § |

| Fever (Nr., %) | 6 (100%) | 79 (96.3%) | 1.000 ‡ |

| Koplik sign (Nr., %) | 4 (66.7%) | 58 (70.7%) | 1.000 ‡ |

| Days—Exanthema—Admission (Median (IQR)) (N = 86) | 2 (0–3.25) | 2 (1–2) | 0.909 § |

| Complications (Nr., %) | |||

| Pneumonia | 5 (83.3%) | 75 (91.5%) | 0.446 ‡ |

| Respiratory failure | 0 (0%) | 13 (15.9%) | 0.586 ‡ |

| Encephalitis | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Hospitalization period (Median (IQR)) | 4 (3–4.5) | 5 (4–6) | 0.103§ |

| Laboratory parameters (Median (IQR)) | |||

| Neutrophils (cells/μL) | 4300 (3325–4775) | 4300 (3300–5550) | 0.772 § |

| Lymphocytes (cells/μL) | 600(275–825) | 500(400–700) | 0.914 § |

| NLR | 8.28 (5.24–12) | 8.33 (6.22–11.91) | 0.728 § |

| AST (UI/mL) (N = 85) | 241(38–252) | 117(64–229) | 0.878 § |

| ALT(UI/mL) | 172(37–353) | 180(66–360.5) | 0.477 § |

| ALT/AST (N = 85) | 1.37 (1.07–1.45) | 1.32 (0.92–1.77) | 0.835 § |

| Antibiotic treatment (Nr., %) | 4 (66.7%) | 55 (67.1%) | 1.000 ‡ |

| Parameter/Ocular Lesions Type (N = 82) | Other (N = 29) | Keratitis (N = 53) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (Female) (Nr., %) | 13 (44.8%) | 25 (47.2%) | 1.000 ‡ |

| Age (Median (IQR)) | 32 (24–45) | 34 (24–43.5) | 0.973 § |

| Workplace domain (Nr., %) (N = 78) | |||

| Other (N = 68) | 24 (85.7%) | 44 (88%) | 0.740 ‡ |

| Healthcare (N = 10) | 4 (14.3%) | 6 (12%) | |

| Environment (Urban) (Nr., %) | 16 (55.2%) | 35 (66%) | 0.351 ‡ |

| Education (Nr., %) (N = 65) | |||

| Primary (N = 7) | 1 (3.8%) | 6 (15.4%) | 0.019 ‡ |

| Secondary (N = 32) | 14 (53.8%) | 18 (46.2%) | |

| Academic (N = 19) | 11 (42.3%) | 8 (20.5%) | |

| No education (N = 7) | 0 (0%) | 7 (17.9%) | |

| History—Travel (Nr., %) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| History—Antibiotic treatment (Nr., %) | 9 (31%) | 14 (26.4%) | 0.798 ‡ |

| Health insurance (Nr., %) | 23 (79.3%) | 42 (79.2%) | 1.000 ‡ |

| Medical history—Measles (Nr., %) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Symptoms | |||

| Days—Onset—Admission (Median (IQR)) (N = 81) | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) | 0.964 § |

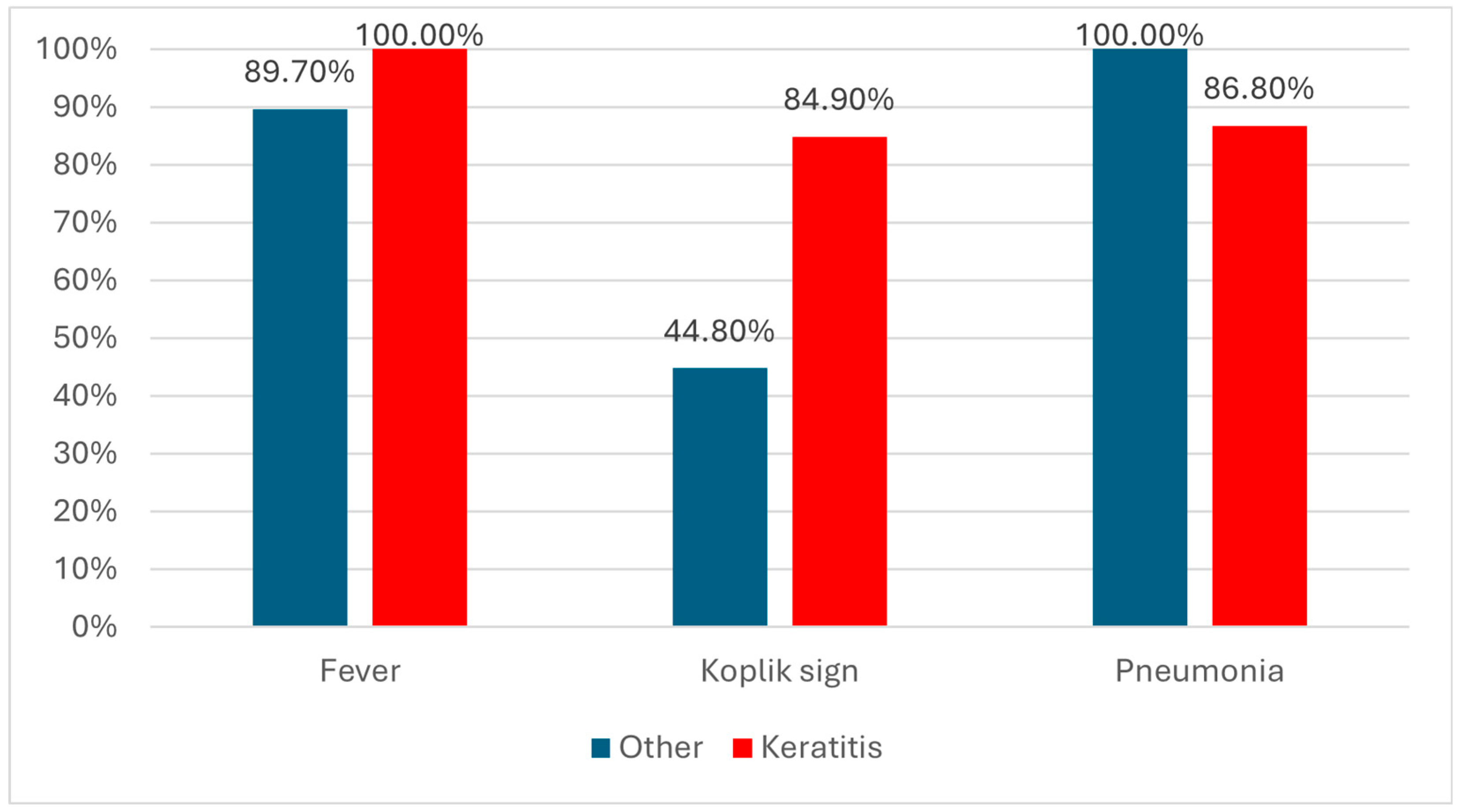

| Fever (Nr., %) | 26 (89.7%) | 53 (100%) | 0.041 ‡ |

| Koplik sign (Nr., %) | 13 (44.8%) | 45 (84.9%) | <0.001 ‡ |

| Days—Exanthema—Admission (Median (IQR)) (N = 80) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | 0.776 § |

| Complications (Nr., %) | |||

| Pneumonia | 29 (100%) | 46 (86.8%) | 0.048 ‡ |

| Respiratory failure | 7 (24.1%) | 6 (11.3%) | 0.204 ‡ |

| Encephalitis | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Hospitalization period (Median (IQR)) | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) | 0.698 § |

| Laboratory parameters (Median (IQR)) | |||

| Neutrophils (cells/μL) | 4500 (3600–5200) | 4000 (3200–5800) | 0.516 § |

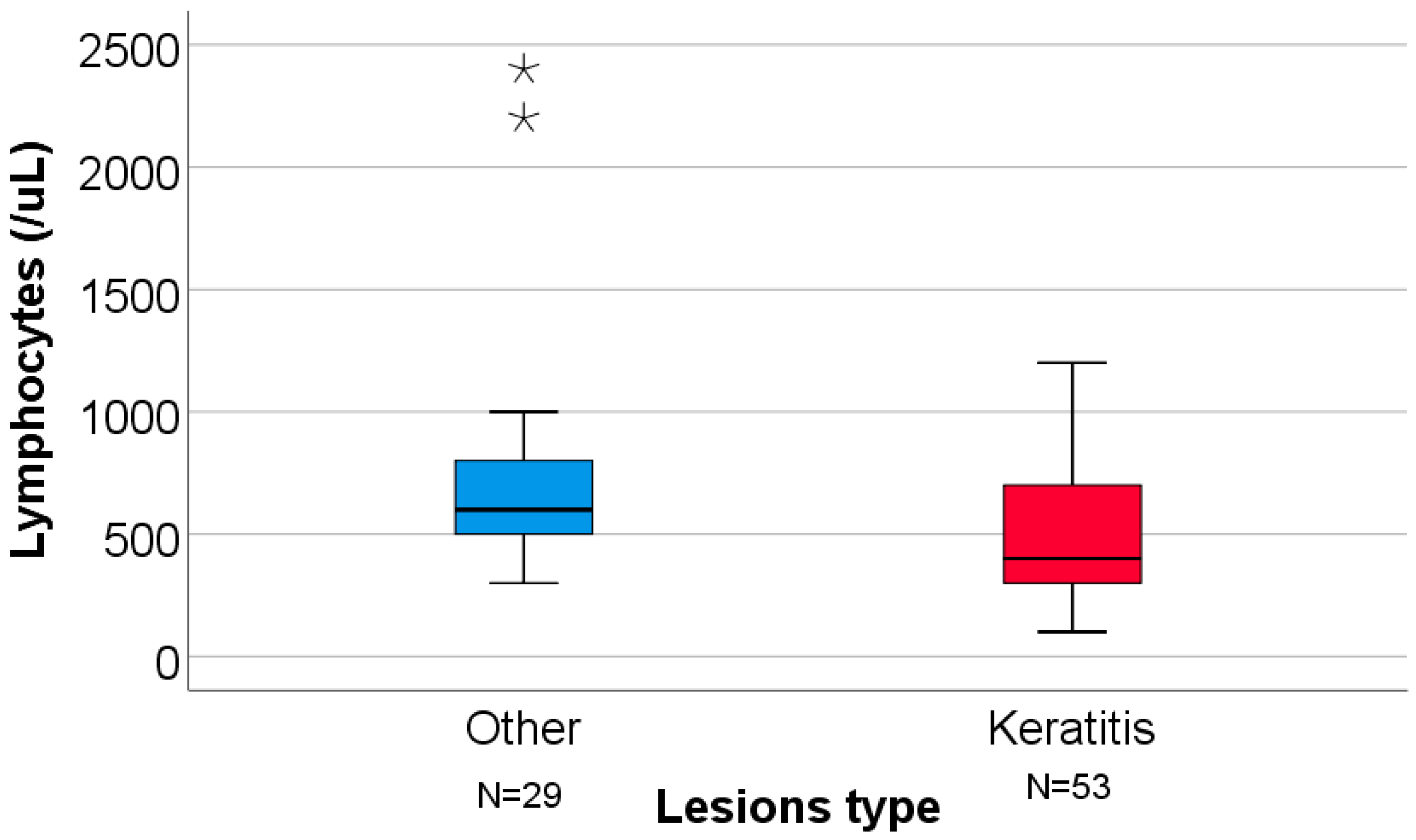

| Lymphocytes (cells/μL) | 600 (500–800) | 400 (300–700) | 0.004 § |

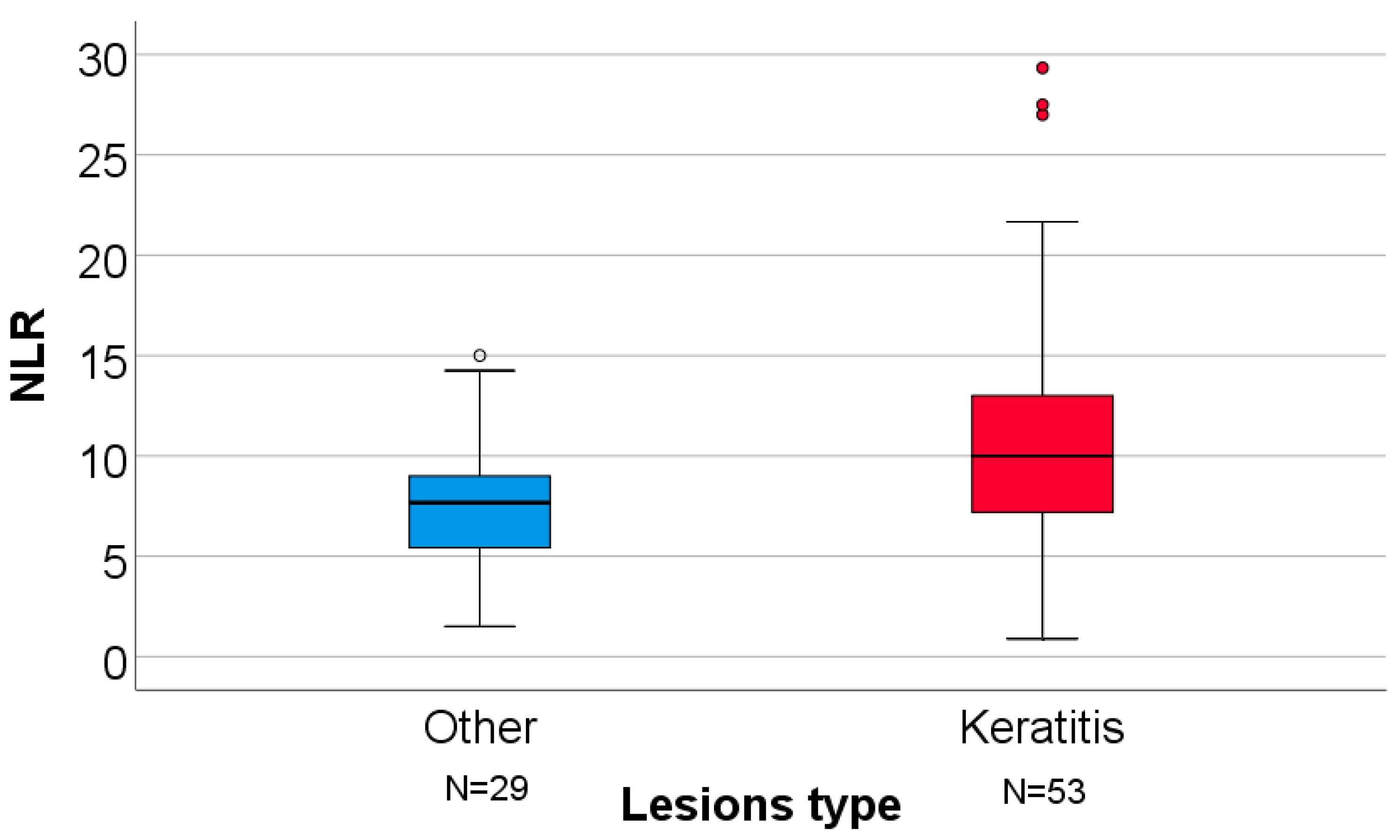

| NLR | 7.66 (4.83–9.33) | 10 (7.1–13.1) | 0.016 § |

| AST (UI/mL) (N = 80) | 118 (78–173) | 116 (51–241.5) | 0.963 § |

| ALT (UI/mL) | 191 (75.5–277) | 179 (58–490.5) | 0.907 § |

| ALT/AST (N = 80) | 1.38 (1.03–2) | 1.22 (0.92–1.74) | 0.360 § |

| Antibiotic treatment (Nr., %) | 21 (72.4%) | 34 (64.2%) | 0.474 ‡ |

| Parameter/Koplik Sign (N = 250) | Negative (N = 90) | Positive (N = 160) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (Female) (Nr., %) | 53 (58.9%) | 78 (48.8%) | 0.147 ‡ |

| Age (Median (IQR)) | 30.5 (22–43) | 34 (24–43) | 0.136 § |

| Workplace domain (Nr., %) (N = 239) | |||

| Other (N = 213) | 74 (87.1%) | 139 (90.3%) | 0.516 ‡ |

| Healthcare (N = 26) | 11 (12.9%) | 15 (9.7%) | |

| Environment (Urban) (Nr., %) (N = 198) | 55 (61.1%) | 95 (59.4%) | 0.893 ‡ |

| Education (Nr., %) | |||

| Primary (N = 22) | 6 (8.1%) | 16 (12.9%) | 0.475 ‡ |

| Secondary (N = 105) | 37 (50%) | 68 (54.8%) | |

| Academic (N = 39) | 18 (24.3%) | 21 (16.9%) | |

| No education (N = 32) | 13 (17.6%) | 19 (15.3%) | |

| History—Travel (Nr., %) (N = 249) | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (0.6%) | 1.000 ‡ |

| History—Antibiotic treatment (Nr., %) | 28 (31.1%) | 46 (28.7%) | 0.773 ‡ |

| Health insurance (Nr., %) | 61 (67.8%) | 121 (75.6%) | 0.186 ‡ |

| Medical history—Measles (Nr., %) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 1.000 ‡ |

| Symptoms | |||

| Days—Onset—Admission (Median (IQR)) (N = 249) | 5 (4–7) | 5 (4–5) | 0.027 § |

| Fever (Nr., %) | 84 (93.3%) | 158 (98.8%) | 0.027 ‡ |

| Days—Exanthema—Admission (Median (IQR)) (N = 243) | 2 (1–3) | 1 (1–2) | 0.295 § |

| Complications (Nr., %) | |||

| Pneumonia | 78 (86.7%) | 138 (86.3%) | 1.000 ‡ |

| Respiratory failure | 15 (16.7%) | 26 (16.3%) | 1.000 ‡ |

| Encephalitis | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 1.000 ‡ |

| Hospitalization period (Median (IQR)) | 4.5 (3–6) | 4 (4–6) | 0.730 § |

| Laboratory parameters (Median (IQR)) | |||

| Neutrophils (cells/μL) | 4300(3250–5425) | 4550(3300–5700) | 0.591 § |

| Lymphocytes (cells/μL) | 600 (400–800) | 500 (400–700) | 0.294 § |

| NLR | 7.7 (4.75–11) | 8.07 (5.75–12) | 0.247 § |

| AST (UI/mL) (N = 241) | 100 (59–173) | 112 (61–233) | 0.195 § |

| ALT (UI/mL) (N = 249) | 142 (48–272) | 144 (67–350) | 0.163 § |

| ALT/AST (N = 241) | 1.26 (0.92–1.65) | 1.33 (0.97–1.69) | 0.604 § |

| Antibiotic treatment (Nr., %) | 60 (66.7%) | 104 (65%) | 0.890 ‡ |

| Parameter/Pneumonia (N = 250) | Absent (N = 34) | Present (N = 216) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (Female) (Nr., %) | 22 (64.7%) | 109 (50.5%) | 0.141 ‡ |

| Age (Median (IQR)) | 27 (23–38) | 34 (24–43) | 0.098 § |

| Workplace domain (Nr., %) (N = 239) | |||

| Other (N = 213) | 26 (81.3%) | 187 (90.3%) | 0.132 ‡ |

| Healthcare (N = 26) | 6 (18.8%) | 20 (9.7%) | |

| Environment (Urban) (Nr., %) (N = 198) | 17 (50%) | 133 (61.6%) | 0.258 ‡ |

| Education (Nr., %) | |||

| Primary (N = 22) | 4 (13.3%) | 18 (10.7%) | 0.810 ‡ |

| Secondary (N = 105) | 17 (56.7%) | 88 (52.4%) | |

| Academic (N = 39) | 4 (13.3%) | 35 (20.8%) | |

| No education (N = 32) | 5 (16.7%) | 27 (16.1%) | |

| History—Travel (Nr., %) (N = 249) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.9%) | 1.000 ‡ |

| History—Antibiotic treatment (Nr., %) | 12 (35.3%) | 62 (28.7%) | 0.426 ‡ |

| Health insurance (Nr., %) | 26 (76.5%) | 156 (72.2%) | 0.683 ‡ |

| Symptoms | |||

| Days—Onset—Admission (Median (IQR)) (N = 249) | 5 (3.75–6.25) | 5 (4–6) | 0.794 § |

| Fever (Nr., %) | 32 (94.1%) | 210 (97.2%) | 0.298 ‡ |

| Days—Exanthema—Admission (Median (IQR)) (N = 243) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 0.134 § |

| Complications (Nr., %) | |||

| Respiratory failure | 1 (2.9%) | 40 (18.5%) | 0.023 ‡ |

| Encephalitis | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1.000 ‡ |

| Hospitalization period (Median (IQR)) | 4 (3–5) | 4.5 (4–6) | 0.054 § |

| Laboratory parameters (Median (IQR)) | |||

| Neutrophils (cells/μL) | 3750 (2850–5475) | 4500 (3400–5675) | 0.232 § |

| Lymphocytes (cells/μL) | 600 (400–700) | 500 (400–800) | 0.785 § |

| NLR | 6.76 (5.45–10.56) | 8.2 (5.47–11.68) | 0.261 § |

| AST (UI/mL) (N = 241) | 75 (57–230.5) | 115.5 (60–218) | 0.437 § |

| ALT (UI/mL) (N = 249) | 98 (57–357.5) | 158 (65–299.75) | 0.354 § |

| ALT/AST (N = 241) | 1.14 (0.89–1.47) | 1.31 (0.96–1.69) | 0.265 § |

| Antibiotic treatment (Nr., %) | 16 (47.1%) | 148 (68.5%) | 0.019 ‡ |

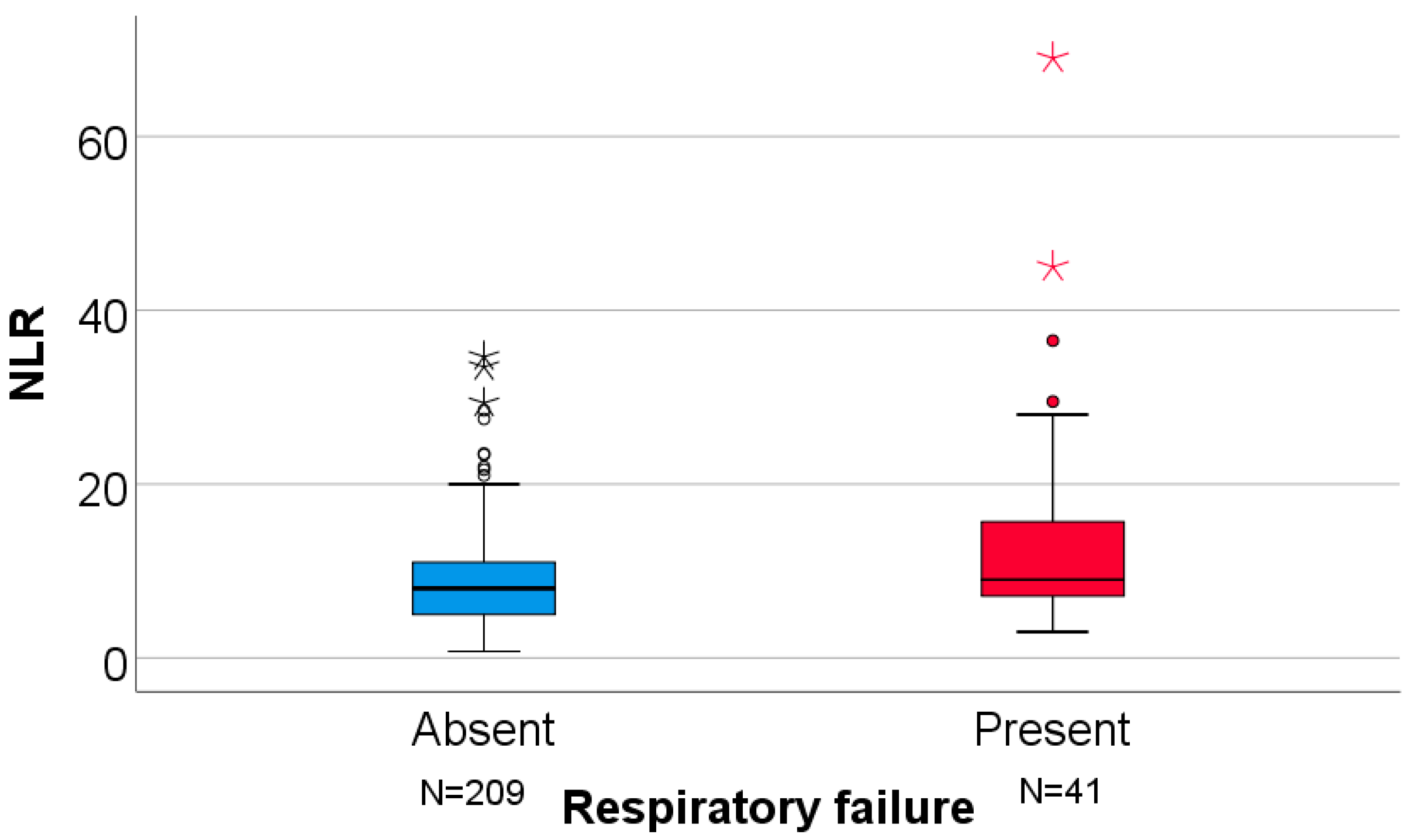

| Parameter/Respiratory Failure (N = 250) | Absent (N = 209) | Present (N = 41) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (Female) (Nr., %) | 119 (56.9%) | 12 (29.3%) | 0.002 ‡ |

| Age (Median (IQR)) | 32 (23–42) | 37 (24.5–45) | 0.049 § |

| Workplace domain (Nr., %) (N = 239) | |||

| Other (N = 213) | 175 (87.9%) | 38 (95%) | 0.269 ‡ |

| Healthcare (N = 26) | 24 (12.1%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Environment (Urban) (Nr., %) (N = 198) | 122 (58.4%) | 28 (68.3%) | 0.296 ‡ |

| Education (Nr., %) | |||

| Primary (N = 22) | 17 (10.2%) | 5 (16.1%) | 0.560 ‡ |

| Secondary (N = 105) | 87 (52.1%) | 18 (58.1%) | |

| Academic (N = 39) | 35 (21%) | 4 (12.9%) | |

| No education (N = 32) | 28 (16.8%) | 4 (12.9%) | |

| History—Travel (Nr., %) (N = 249) | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1.000 ‡ |

| History—Antibiotic treatment (Nr., %) | 63 (30.1%) | 11 (26.8%) | 0.713 ‡ |

| Health insurance (Nr., %) | 154 (73.7%) | 28 (68.3%) | 0.565 ‡ |

| Medical history—Measles (Nr., %) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1.000 ‡ |

| Symptoms | |||

| Days—Onset—Admission (Median (IQR)) (N = 249) | 5 (3–6) | 5 (4–7) | 0.034 § |

| Fever (Nr., %) | 204 (97.6%) | 38 (92.7%) | 0.127 ‡ |

| Days—Exanthema—Admission (Median (IQR)) (N = 243) | 1.5 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 0.390 § |

| Complications (Nr., %) | |||

| Encephalitis | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1.000 ‡ |

| Hospitalization period (Median (IQR)) | 4 (3.5–6) | 5 (4–6) | 0.171 § |

| Laboratory parameters (Median (IQR)) | |||

| Neutrophils (cells/μL) | 4100 (3100–5400) | 5200 (4600–6800) | <0.001 § |

| Lymphocytes (cells/μL) | 500 (400–700) | 600 (300–850) | 0.734 § |

| NLR | 8 (5–11.16) | 9 (7–17.08) | 0.025 § |

| AST(UI/mL) (N = 241) | 101 (52.5–225) | 118 (76.5–164) | 0.497 § |

| ALT (UI/mL) (N = 249) | 134 (61.5–315) | 157 (94.5–278) | 0.737 § |

| ALT/AST (N = 241) | 1.31 (0.96–1.66) | 1.31 (0.88–1.74) | 0.782 § |

| Antibiotic treatment (Nr., %) | 129 (61.7%) | 35 (85.4%) | 0.004 ‡ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lazăr, D.Ș.; Nanu, A.-A.; Condurache, I.-A.; Nica, M.; Tudosie, C.; Malciolu-Nica, M.A.; Grigore, A.I.; Gherlan, G.S.; Popescu, C.P.; Florescu, S.A. Patterns of Ocular Involvement and Associated Factors in Adult Measles: A Retrospective Study from a Romanian Tertiary Hospital. Clin. Pract. 2026, 16, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract16010004

Lazăr DȘ, Nanu A-A, Condurache I-A, Nica M, Tudosie C, Malciolu-Nica MA, Grigore AI, Gherlan GS, Popescu CP, Florescu SA. Patterns of Ocular Involvement and Associated Factors in Adult Measles: A Retrospective Study from a Romanian Tertiary Hospital. Clinics and Practice. 2026; 16(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract16010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleLazăr, Dragoș Ștefan, Adina-Alexandra Nanu, Ilie-Andrei Condurache, Maria Nica, Catrinel Tudosie, Maria Alexandra Malciolu-Nica, Alexandra Ioana Grigore, George Sebastian Gherlan, Corneliu Petru Popescu, and Simin Aysel Florescu. 2026. "Patterns of Ocular Involvement and Associated Factors in Adult Measles: A Retrospective Study from a Romanian Tertiary Hospital" Clinics and Practice 16, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract16010004

APA StyleLazăr, D. Ș., Nanu, A.-A., Condurache, I.-A., Nica, M., Tudosie, C., Malciolu-Nica, M. A., Grigore, A. I., Gherlan, G. S., Popescu, C. P., & Florescu, S. A. (2026). Patterns of Ocular Involvement and Associated Factors in Adult Measles: A Retrospective Study from a Romanian Tertiary Hospital. Clinics and Practice, 16(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract16010004