Mustardé Cheek Rotation-Advancement Flap: A Case-Based Experience in Reconstruction of a Large Defect of the Lower Eyelid Due to Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

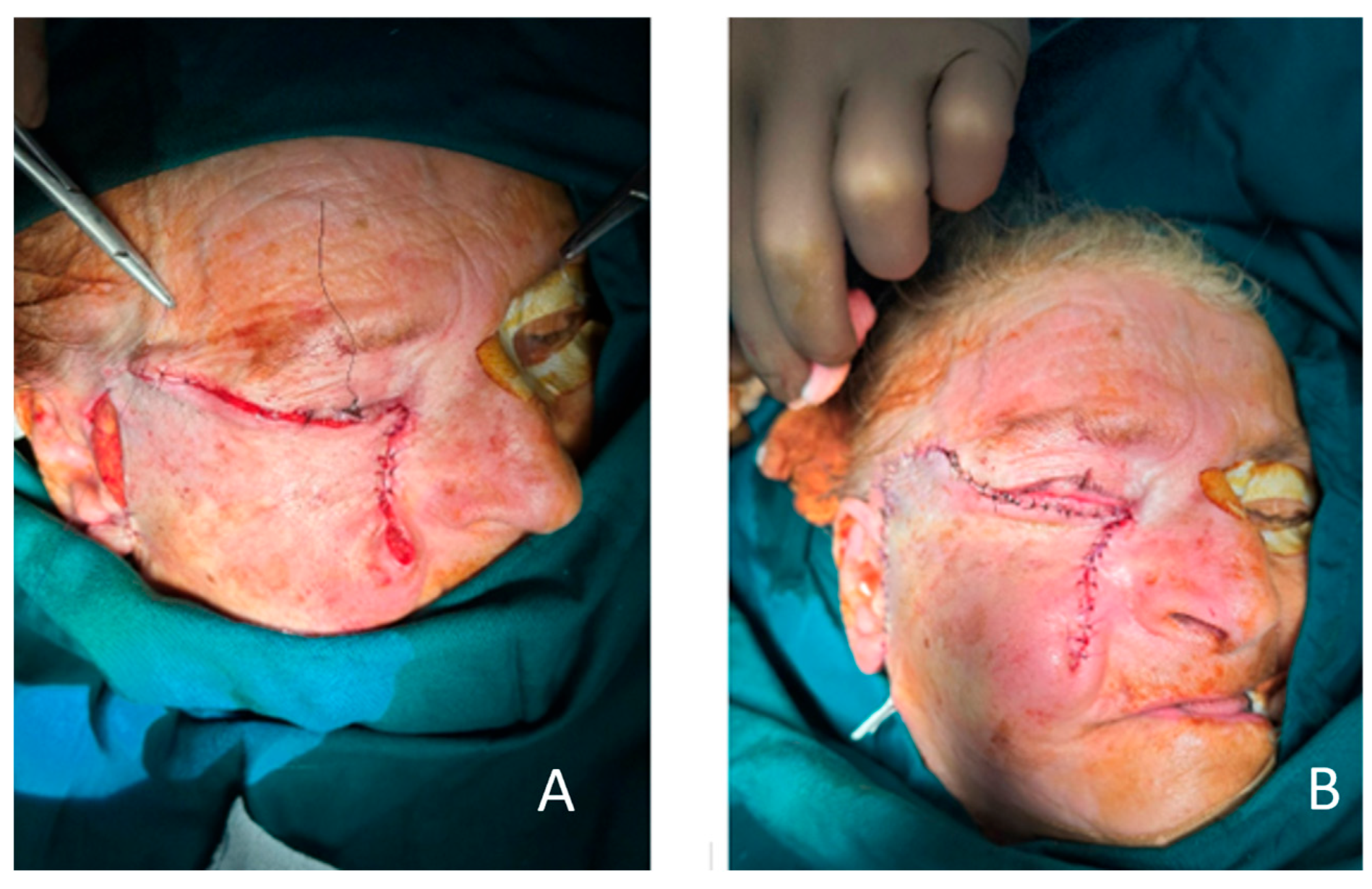

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

3.1. Surgical Anatomy Considerations

3.2. Consideration of Different Techniques

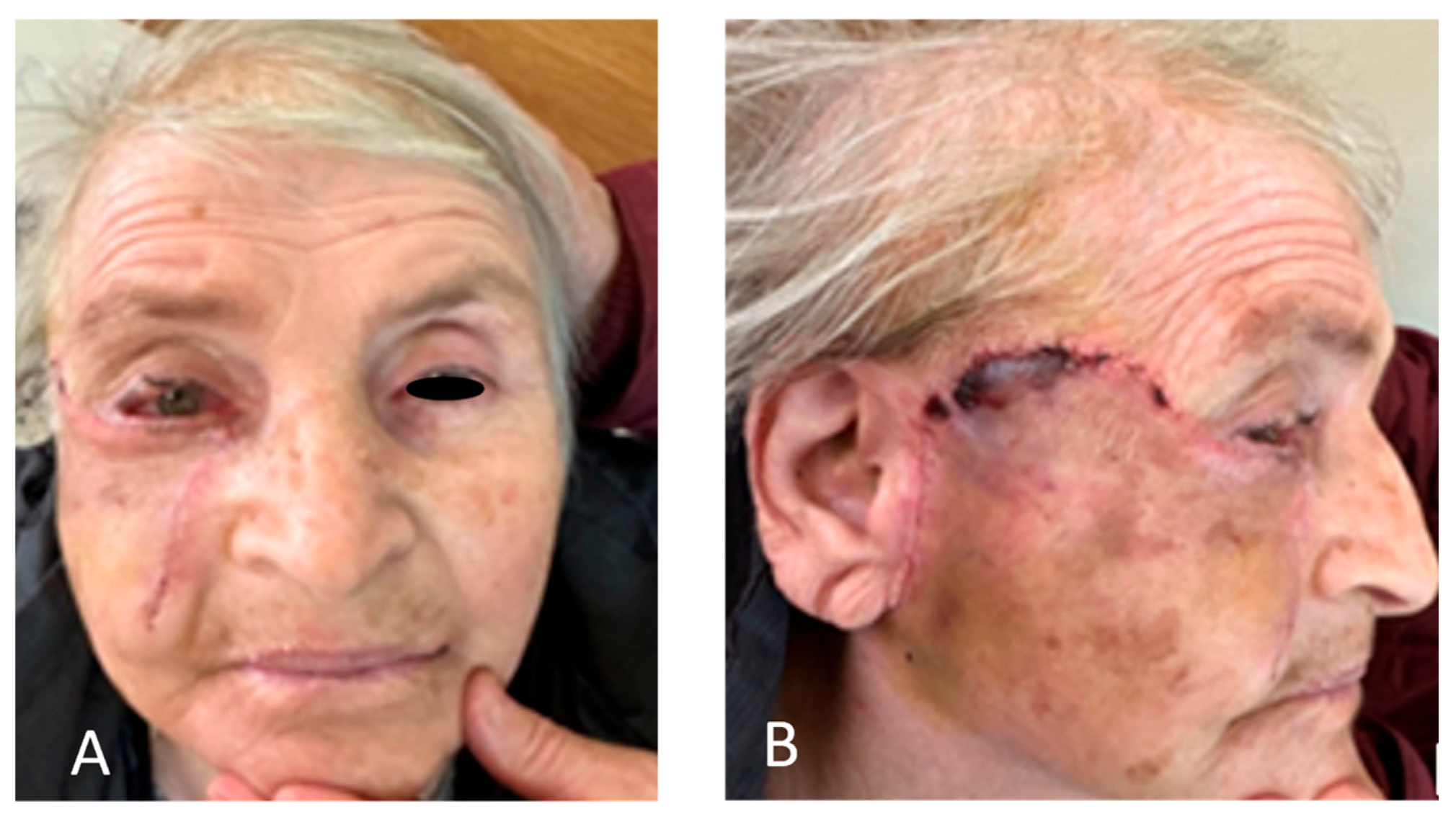

4. Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCC | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| SOOF | Suborbicularis oculi fascia |

| SMAS | Superficial musculoaponeurotic system |

References

- Nguyen, J.D.; Duong, H. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Face. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gigov, K.; Ginev, I.; Minev, I.; Kavradzhieva, P. Three-Layer Reconstruction of a Full-Thickness Nasal Alar Defect after Basal-Cell Carcinoma Removal. Reports 2024, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Fu, R.; Ji, Q.; Liu, C.; Yang, J.; Yin, X.; Oranges, C.M.; Li, Q.; Huang, R.L. Surgical Strategies for Eyelid Defect Reconstruction: A Review on Principles and Techniques. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2022, 11, 1383–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, N.; Ogi, H.; Yanagibayashi, S.; Yoshida, R.; Takikawa, M.; Nishijima, A.; Kiyosawa, T. Eyelid Reconstruction Using Oral Mucosa and Ear Cartilage Strips as Sandwich Grafting. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2017, 5, e1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, S.; Panda, S.; Singh, C.A.; Thakar, A. Modified Mustardé Flap for Lower Eyelid Reconstruction in Basal Cell Carcinoma: Revisited. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 75, 2492–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neligan, P.C. Craniofacial, Head and Neck Surgery. In Plastic Surgery, 5th ed.; Neligan, P.C., Ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2023; Volume 3, pp. 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson, B.C. Herniated Fat and the Orbital Septum of the Lower Eyelid. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1993, 20, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Colley, P. Surgical Orbital Anatomy. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2019, 33, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, K.C. Lower Eyelid Anatomy. In Grabb and Smith’s Plastic Surgery, 9th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW): Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2024; Chapter 36. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, M.L.; Lopez, M.J.; Czyz, C.N. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Eyelid. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025; Updated 14 August 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482304/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Lize, F.; Leyder, P.; Quilichini, J. Horizontal V-Y Advancement Flap for Lower Eyelid Reconstruction in Young Patients. J. Fr. Ophtalmol. 2015, 38, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orgun, D.; Hayashi, A.; Yoshizawa, H.; Shimizu, A.; Horiguchi, M.; Mochizuki, M.; Kamimori, T.; Aiba-Kojima, E.; Mizuno, H. Oncoplastic Lower Eyelid Reconstruction Analysis. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2019, 30, 2396–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervatiuc, M.; Reshetov, I.V.; Saakyan, S.V.; Jonnazarov, E.; Shklyaruk, L.V.; Dzhapiev, N.U.; Tursunov, B.A. Eyelid Reconstruction Methods: A 10-Year Review. Chin. J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2023, 5, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, P.; Mykula, R.; Griffiths, R.W. Ectropion Following Excision of Lower Eyelid Tumours and Full Thickness Skin Graft Repair. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 2005, 58, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz Salas, V. A Novel Approach to the Reconstruction of a Large Surgical Defect in the Cheek. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubino, C.; Farace, F.; Puddu, A.; Canu, V.; Posadinu, M. Total Upper and Lower Eyelid Replacement Following Thermal Burn Using an ALT Flap—A Case Report. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2008, 61, 578–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gąsiorowski, K.; Gontarz, M.; Bargiel, J.; Marecik, T.; Szczurowski, P.; Wyszyńska-Pawelec, G. Reconstructive Techniques Following Malignant Eyelid Tumour Excision—Our Experience. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamakawa, S.; Suda, S.; Hayashida, K. A New Lower Eyelid Reconstruction Using Transverse Facial Artery Perforator Flap Based on an Anatomical Study. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2023, 77, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibanez-Flores, N.; Bruzual-Lezama, C.; Castellar-Cerpa, J.J.; Fernandez-Montalvo, L. Lower Eyelid Reconstruction with Pericranium Graft and Mustardé Flap. Arch. Soc. Española Oftalmol. 2019, 94, 514–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Delgado, K.E.; Pedraza Falcón, C.E.; Castro Cordero, V.A.; Delgado Duarte, R.; Montaño Vásquez del Mercado, F.A.; Landeros Rosales, E.V.; Páramo Hernández, D.L.; De Los Santos Vega, R.; Castro Serrano, L.S.; López Almanza, I.M.; et al. Lower Eyelid Reconstruction with Mustardé Flap. Int. J. Med. Sci. Clin. Res. Stud. 2024, 4, 1069–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, M.A.; Callahan, A. Mustardé Flap Lower Lid Reconstruction after Malignancy. Ophthalmology 1980, 87, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, R.; Kohan, N.K. Mustarde Flap. In Encyclopedia of Ophthalmology; Schmidt-Erfurth, U., Kohnen, T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieniek, A.; Chlebicka, I.; Kliniec, K.; Szepietowski, J.C. “Floating Island Flap”—A New Technique for the Reconstruction of Full-Thickness Lower Eyelid Defects with Spontaneous Healing (Folded V-Y Island Flap with Orbicularis Oculi Muscle). J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasopoulos, I.; Ntamagkas, A.; Chrysikos, D.; Patelis, A.; Troupis, T. Basal Cell Carcinoma of the Right Lower Eyelid Treated with Tarsoconjunctival and Mustardé Flaps. Cureus 2025, 17, e79129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gigov, K.; Ginev, I.; Kavradzhieva, P. Mustardé Cheek Rotation-Advancement Flap: A Case-Based Experience in Reconstruction of a Large Defect of the Lower Eyelid Due to Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15090165

Gigov K, Ginev I, Kavradzhieva P. Mustardé Cheek Rotation-Advancement Flap: A Case-Based Experience in Reconstruction of a Large Defect of the Lower Eyelid Due to Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clinics and Practice. 2025; 15(9):165. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15090165

Chicago/Turabian StyleGigov, Kostadin, Ivan Ginev, and Petra Kavradzhieva. 2025. "Mustardé Cheek Rotation-Advancement Flap: A Case-Based Experience in Reconstruction of a Large Defect of the Lower Eyelid Due to Squamous Cell Carcinoma" Clinics and Practice 15, no. 9: 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15090165

APA StyleGigov, K., Ginev, I., & Kavradzhieva, P. (2025). Mustardé Cheek Rotation-Advancement Flap: A Case-Based Experience in Reconstruction of a Large Defect of the Lower Eyelid Due to Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clinics and Practice, 15(9), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15090165