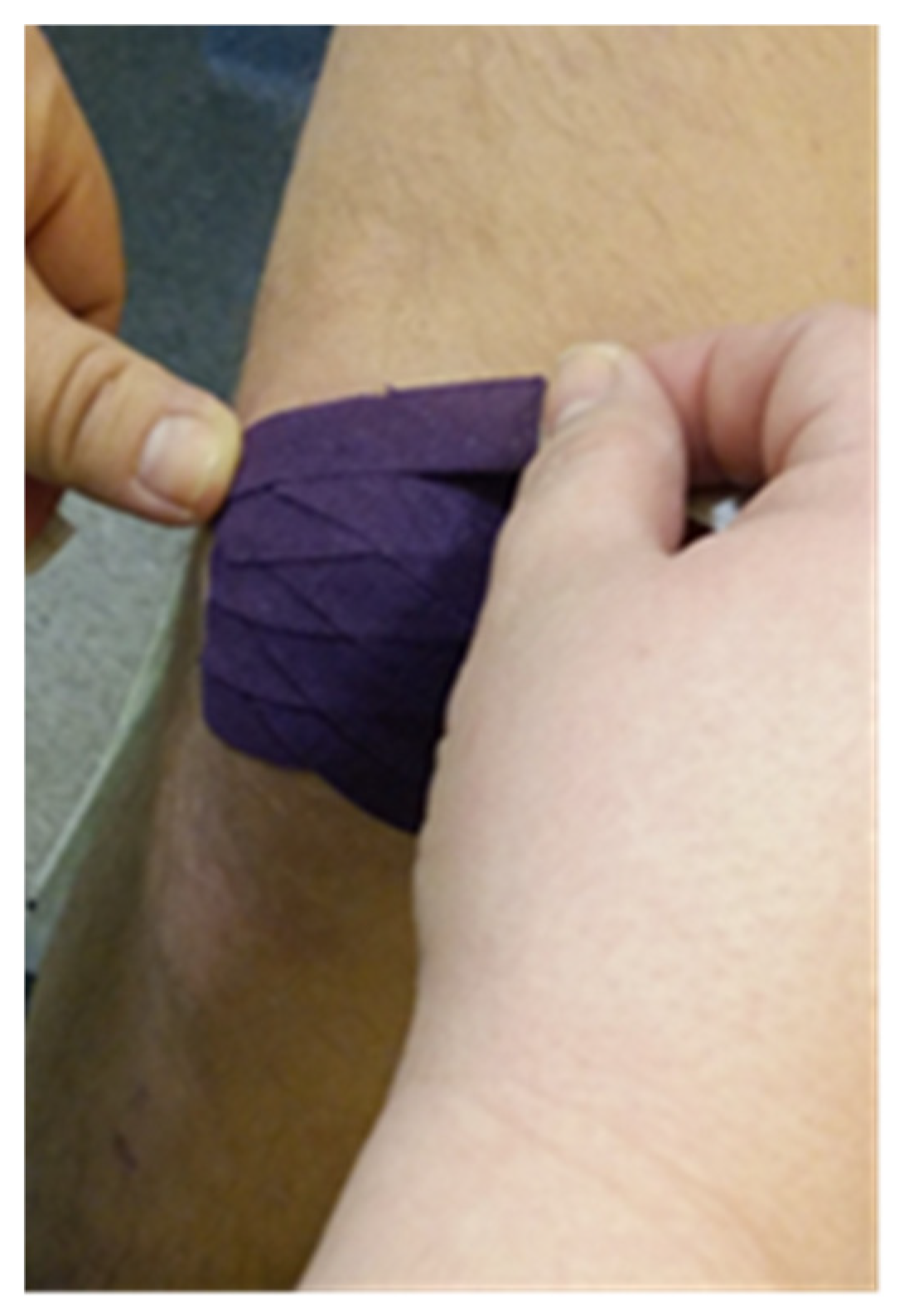

Assessment of the Effect of Kinesiology Taping on Scar Treatment in Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material and Methods

- -

- Group G1 included 9 patients diagnosed with keloid scar;

- -

- Group G2 included 14 patients diagnosed with hypertrophic scar;

- -

- Group G3 included 7 patients diagnosed with postoperative adhesions.

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

- -

- The patient’s age 4–10 years old;

- -

- Wound healing and scar formation with no signs of cracks. The scar could only be included in the study three weeks after it had healed;

- -

- The scar age does not exceed 1 year;

- -

- The scar size has a length and width up to 15 cm.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

- -

- Wound not healed;

- -

- Discontinuation of treatment, failure to perform a check-up within a specified time (8 weeks from the first examination);

- -

- A child’s intolerance of specific treatment, e.g., patch allergy/intertrigo;

- -

- Cancer.

2.1.3. Stage I: I Taking Measurements

- -

- Scar assessment using: the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS), including the following features: perfusion, height/thickness, deformability, pigmentation;

- -

- Ultrasound assessment of the scar morphology. TOSHIBA APILO 500 ultrasound scanner (Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan) was used for measurements; in order to standardize the results of the USG, only two dimensions were specified: the thickness and width of the scar.

- -

- Measurements were taken using the following:

- -

- The Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS);

- -

- Ultrasound examination.

3. Results

3.1. The Analysis of the Vancouver Scar Scale Scores Against the Scar Type

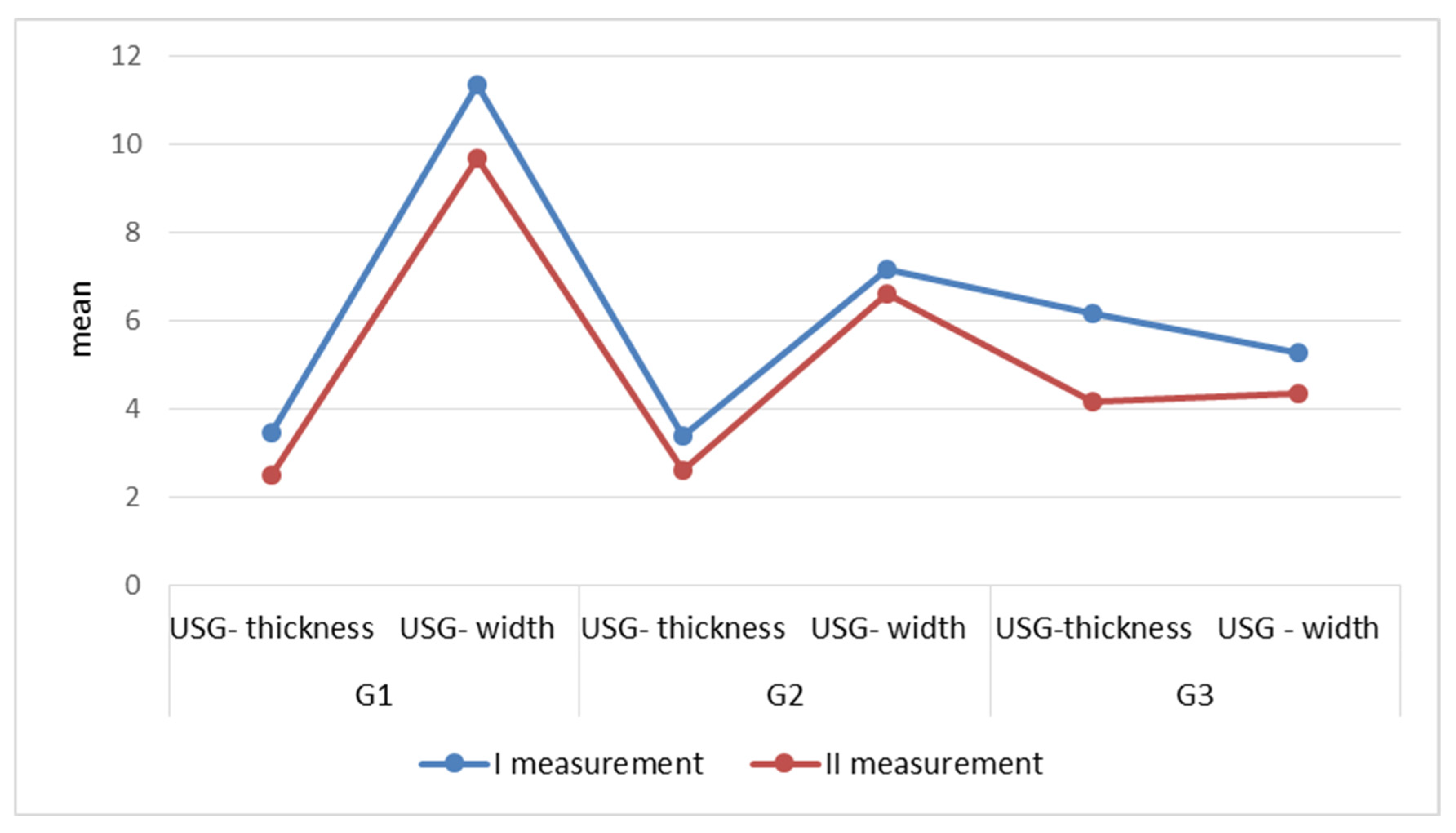

3.2. The Analysis of Scar Quantitative Parameters in USG Assessment Against the Scar Type

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KT | Kinesiology taping |

| USG | Ultrasound |

| VSS | Vancouver Scar Scale |

| Fig. | Figure |

| Tab. | Table |

References

- Osiak, K. Przerostowe blizny, bliznowce i przykurcze bliznowate. Post. Nauk. Med. 2005, 18, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, R. Keloid and Hypertrophic Scars Are the Result of Chronic Inflammation in the Reticular Dermis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustoe, T.A.; Cooter, R.D.; Gold, M.H.; Hobbs, F.D.; Ramelet, A.A.; Shakespeare, P.G.; Stella, M.; Téot, L.; Wood, F.M.; Ziegler, U.E. International Advisory Panel on Scar Management. International Clinical recommendations on scar management. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2002, 110, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.A.; Feldstein, S.I.; Shumaker, P.R.; Krakowski, A.C. A review of scar assessmentscales. Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2015, 34, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, U.E. International clinical recommendations on scar. Zentralbl. Chir. 2004, 129, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monstrey, S.; Middelkoop, E.; Vranckx, J.J.; Bassetto, F.; Ziegler, U.E.; Meaume, S.; Téot, L. Updated scar management practical guidelines: Non-invasive and invasive measures. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2014, 67, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chike-Obi, C.h.J.; Cole, P.D.; Brissett, A.E. Keloids: Pathogenesis, Clinical Features and Management. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2009, 23, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, P.M.; Askay, S.W.; Patterson, D.R. Pain, depression, and physical functioning following burn injury. Rehabil. Psychol. 2009, 54, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, R. The most current algorithms for the treatment and prevention of hyper trophic scars and keloids. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 125, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admani, S.; Gertner, J.W.; Grosman, A.; Shumaker, P.R.; Uebelhoer, N.S.; Krakowski, A. Multidisciplinary, multimodal approach for a child with a traumatic facial scar. Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2015, 34, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, S.; Bao, E.; Rothberg, S.; Palacios, J.; Smith, I.; Tanna, N.; Bastidas, N. Scar Management in Pediatric Patients. Medicina 2025, 61, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassett, K.T.; Lingman, S.A.; Ellis, R.F. The use and treatment efficacy of kinaesthetic taping for musculoskeletal conditions: A systematic review. J. Physiother. 2010, 38, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bac, A.; Stagraczyński, Ł.; Ciszek, E.; Górkiewicz, M.; Szczygieł, A. Skuteczność rehabilitacji metodą Kinesio taping u dzieci ze skoliozą niskokątową. Fizjoter. Pol. 2009, 3, 202–210. [Google Scholar]

- Vercelli, S.; Ferriero, G.; Sartorio, F.; Cisari, C.; Bravini, E. Clinimetric properties and clinical utility in rehabilitation of postsurgical scar rating scales: A systematic review. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2015, 38, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.C.; Dretzke, J.; Grover, L.; Logan, A.; Moiemen, N. A systematic review of objective burn scar measurements. Burns Trauma. 2016, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, A.; McGrouther, D.A.; Ferguson, M.W. Skin scarring. BMJ 2003, 326, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagłaj, M.; Bagłaj, M. Blizny jako problem kliniczny w praktyce dermatologa estetycznego. Dermatol. Estet. 2014, 2, 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, R.; Akita, S.; Akaishi, S.; Aramaki-Hattori, N.; Dohi, T.; Hayashi, T.; Kishi, K.; Kono, T.; Matsumura, H.; Muneuchi, G.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of keloids and hypertrophic Scars-Japan scar workshop consensus document 2018. Burn. Trauma 2019, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liuzzi, F.; Chadwick, S.; Shah, M. Paediatric post-burn scar management in the UK: A national survey. Burns 2015, 41, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumsey, N.; Clarke, A.; White, P. Exploring the psychosocial concerns of outpatients with disfiguring conditions. J. Wound Care 2003, 12, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubińska, A.; Mosiejczuk, H.; Rotter, I. Kinesiotaping w leczeniu obrzęku limfatycznego kończyny górnej u pacjentki po operacji raka piersi—Studium przypadku. Pom. J. Life Sci. 2015, 61, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipińska, A.; Śliwiński, Z.; Kiebzak, W.; Senderek, T.; Kirenko, T. Wpływ aplikacji kinesiotapingu na obrzęk limfatyczny kończyny górnej u kobiet po mastektomii. Fizjoter. Pol. 2007, 7, 258–269. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Pop, B.; Borowska, B.; Tymczak, M.; Hałas, I.; Banaś, J. The influence of kinesiology taping on the reduction of lymphedema among woman after mastectomy -preliminary study. Contemp. Oncol. 2014, 18, 124–129. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Mędrak, A.; Król, T.; Michałek-Król, K.; Dąbrowska-Galas, M. Kinesio Taping and the effect placebo. Med. Rodz. 2017, 20, 304–309. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Śliwiński, Z.; Krajczy, M.; Szczegielniak, J.; Senderka, T. Dynamiczne Plastrowanie; Markmed Rehabilitacja: Wrocław, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Karwacinska, J.; Kiebzak, W.; Stepanek-Finda, B.; Kowalski, I.M.; Protasiewicz-Faldowska, H.; Trybulski, R.; Starczynska, M. Effectiveness of kinesio taping on hypertrophic scars, keloids and scar contractures. Pol. Ann. Med. 2012, 19, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogorzelska, J.; Kiebzak, W.; Starczyńska, M.; Zięba, M. Obserwacja skuteczności stosowania aplikacji kinesiology taping na blizny wykazujące tendencje do przerastania-opis przypadku. Stud. Med. 2012, 26, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Goodridge, S. Kinsio Tape Application on Hypertrophic Scar Formation. Kinsio Taping Association International. Available online: https://kinesiotaping.com/how-to/kinesio-taping-application-database/ (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- Branstiter, G. The use of Kinesio tape for the management of post-surgical scar tissue. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, USA, 23–26 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fornalski, J. Gojenie się ran z bliznowaceniem—Metody terapeutyczne. Nowa Med. 2006, 4, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Daniszewska-Jarząb, I.; Jarząb, S. Practical application of kinesiotaping in the case of a cesarean section scar. Aesth. Cosmetol. Med. 2020, 9, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, A.M.; Othman, E.M.; Kenawy, A.M.; AboElnour, N.H. Effectiveness of Kinesio Taping Versus Deep Friction Massage on Post Burn Hypertrophic Scar. Curr. Sci. Int. 2019, 7, 775–784. [Google Scholar]

| Scar Type | VSS | Mean | Me | SD | Min | Max | Q1 | Q3 | Wilcoxon Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | (I measurement) | 10.11 | 1.05 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 11 | Z = 2.6413 p = 0.0083 |

| (II measurement) | 6.22 | 1.09 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| G2 | (I measurement) | 10.14 | 1.29 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 11 | Z = 3.2921 p = 0.0010 |

| (II measurement) | 6.14 | 1.10 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6.8 | 8 | ||

| G3 | (I measurement) | 9.14 | 1.95 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 11 | Z = 0.9487 p = 0.3428 |

| (II measurement) | 7.57 | 1.90 | 5 | 6.5 | 8 | 8 | 11 |

| Scar Type | USG I and II Measurement | Mean | Me | SD | Min | Max | Q1 | Q3 | Wilcoxon Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | thickness (I measurement) | 3.46 | 3.50 | 0.46 | 2.70 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 3.80 | Z = 2.6132 p = 0.0090 |

| thickness (II measurement) | 2.50 | 2.00 | 0.76 | 1.60 | 3.50 | 2.00 | 3.20 | ||

| width (I measurement) | 11.36 | 12.00 | 5.87 | 3.50 | 23.00 | 9.00 | 13.00 | Z = 2.6132 p = 0.0089 | |

| width (II measurement) | 9.67 | 9.30 | 5.15 | 3.00 | 21.00 | 8.70 | 10.00 | ||

| G2 | thickness (I measurement) | 3.37 | 2.90 | 1.68 | 1.50 | 7.50 | 2.05 | 4.45 | Z = 3.0237 p = 0.0025 |

| thickness (II measurement) | 2.59 | 2.20 | 1.26 | 1.00 | 5.50 | 1.63 | 3.20 | ||

| width (I measurement) | 7.17 | 5.10 | 7.25 | 2.70 | 31.00 | 3.10 | 7.50 | Z = 2.4768 p = 0.0133 | |

| width (II measurement) | 6.61 | 4.65 | 6.54 | 2.40 | 28.00 | 3.10 | 7.15 | ||

| G3 | thickness (I measurement) | 6.17 | 4.00 | 4.39 | 2.90 | 15.00 | 3.35 | 7.30 | Z = 2.2860 p = 0.0222 |

| thickness (II measurement) | 4.17 | 3.00 | 2.65 | 2.50 | 10.00 | 2.85 | 4.00 | ||

| width (I measurement) | 5.27 | 3.30 | 3.83 | 2.60 | 12.50 | 2.75 | 6.50 | Z = 2.2860 p = 0.0222 | |

| width (II measurement) | 4.33 | 3.00 | 3.41 | 2.00 | 11.50 | 2.15 | 4.75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pogorzelska, J.; Michalska, A.; Zmyślna, A. Assessment of the Effect of Kinesiology Taping on Scar Treatment in Children. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15070131

Pogorzelska J, Michalska A, Zmyślna A. Assessment of the Effect of Kinesiology Taping on Scar Treatment in Children. Clinics and Practice. 2025; 15(7):131. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15070131

Chicago/Turabian StylePogorzelska, Justyna, Agata Michalska, and Anna Zmyślna. 2025. "Assessment of the Effect of Kinesiology Taping on Scar Treatment in Children" Clinics and Practice 15, no. 7: 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15070131

APA StylePogorzelska, J., Michalska, A., & Zmyślna, A. (2025). Assessment of the Effect of Kinesiology Taping on Scar Treatment in Children. Clinics and Practice, 15(7), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15070131