The Association Between COVID-19-Related Persistent Symptoms, Psychological Flexibility, and General Mental Health Among People With and Without Persistent Pain in the UK

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To investigate whether participants with and without persistent pain differed in total persistent symptoms, general mental health, psychological flexibility, and psychological inflexibility. It was hypothesised that participants with persistent pain would report poorer mental health and lower psychological flexibility/higher psychological inflexibility.

- To investigate the correlations between total persistent physical symptoms, psychological (in)flexibility, and general mental health among participants with and without pain respectively. It was hypothesised that a higher number of persistent physical symptoms would be correlated with poorer general mental health, and a higher level of psychological flexibility/lower level of psychological inflexibility would be correlated with better mental health. The correlation between psychological (in)flexibility and persistent physical symptoms was explored.

- To explore if psychological (in)flexibility moderated the relationship between total persistent physical symptoms and general mental health among participants with and without pain respectively.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Procedures

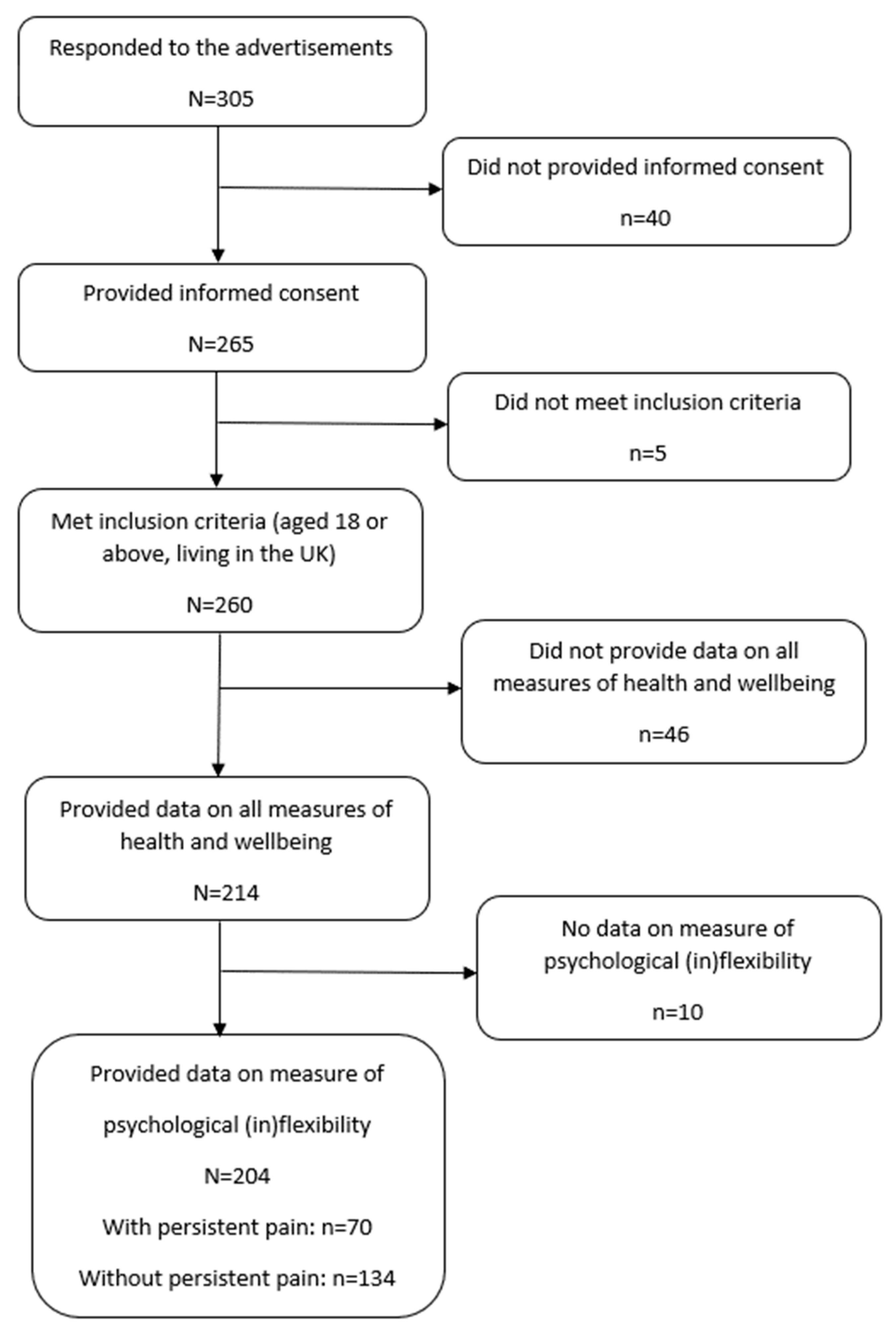

2.3. Participants

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Assessment of Persistent Symptoms

2.4.2. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

2.4.3. General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)

2.4.4. Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)

2.4.5. Multidimensional Psychological Flexibility Inventory (MPFI)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. T-Tests (Study Objective 1)

3.2. Correlations (Study Objective 2)

3.3. Moderation (Study Objective 3)

3.3.1. Moderation Analyses Among Participants with Persistent Pain

3.3.2. Moderation Analyses Among Participants Without Persistent Pain

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of Study Results

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mahmud, S.; Hossain, S.; Muyeed, A.; Islam, M. Mohsin The global prevalence of depression, anxiety, stress, and, insomnia and its changes among health professionals during COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Kioskli, K.; McCracken, L.M. The psychological functioning in the COVID-19 pandemic and its association with psychological flexibility and broader functioning in people with chronic pain. J. Pain 2021, 22, 926–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagé, M.G.; Lacasse, A.; Dassieu, L.; Hudspith, M.; Moor, G.; Sutton, K.; Thompson, J.M.; Dorais, M.; Montcalm, A.J.; Sourial, N.; et al. A cross-sectional study of pain status and psychological distress among individuals living with chronic pain: The Chronic Pain & COVID-19 Pan-Canadian Study. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2021, 41, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, L.M.; Badinlou, F.; Buhrman, M.; Brocki, K.C. The role of psychological flexibility in the context of COVID-19: Associations with depression, anxiety, and insomnia. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2021, 19, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevalence of Ongoing Symptoms Following Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection in the UK: 1 April 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/prevalenceofongoingsymptomsfollowingcoronaviruscovid19infectionintheuk/1april2021 (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- McCracken, L.M.; Badinlou, F.; Buhrman, M.; Brocki, K.C. Psychological impact of COVID-19 in the Swedish population: Depression, anxiety, and insomnia and their associations to risk and vulnerability factors. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, e81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, M.L.; Molldrem, S.; Elliott, A.; Robertson, D.; Keiser, P. Long COVID and mental health correlates: A new chronic condition fits existing patterns. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2023, 11, 2164498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanthanna, H.; Nelson, A.M.; Kissoon, N.; Narouze, S. The COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences for chronic pain: A narrative review. Anaesthesia 2022, 77, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C.D.M.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, J.; Fuensalida-Novo, S.P.; Palacios-Ceña, M.; Gómez-Mayordomo, V.; Florencio, L.L.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.D.M. Myalgia as a symptom at hospital admission by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection is associated with persistent musculoskeletal pain as long-term post-COVID sequelae: A case-control study. Pain 2021, 162, 2832–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lei, J.; Zhang, J.; Yin, L.; Chen, Y.; Xi, Y.; Moreira, J.P. Undiagnosed long COVID-19 in China among non-vaccinated individuals: Identifying persistent symptoms and impacts on patients’ health-related quality of life. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2022, 12, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, N.M.; Harland, K.K.; Krishnadasan, A.; Eyck, P.T.; Mower, W.R.; Willey, J.; Chisolm-Straker, M.; McDonald, L.C.; Kutty, P.K.; Hesse, E.; et al. Diagnosed and undiagnosed COVID-19 in US emergency department health care personnel: A Cross-sectional analysis. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2021, 78, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, D.L.; Golijani-Moghaddam, N. COVID-19: Psychological flexibility, coping, mental health, and wellbeing in the UK during the pandemic. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2020, 17, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.M.; Twohy, A.J.; Smith, G.S. Psychological inflexibility and intolerance of uncertainty moderate the relationship between social isolation and mental health outcomes during COVID-19. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2020, 18, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakenham, K.I.; Landi, G.; Boccolini, G.; Furlani, A.; Grandi, S.; Tossani, E. The moderating roles of psychological flexibility and inflexibility on the mental health impacts of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown in Italy. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2020, 17, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Villatte, M.; Levin, M.; Hildebrandt, M. Open, aware, and active: Contextual approaches as an emerging trend in the behavioral and cognitive therapies. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 7, 141–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Rottenberg, J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepherd, K.; Golijani-Moghaddam, N.; Dawson, D.L. ACTing towards better living during COVID-19: The effects of Acceptance and Commitment therapy for individuals affected by COVID-19. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2022, 23, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien, C.H.; Vallières, A.; Morin, C.M. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001, 2, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, C.M.; Belleville, G.; Bélanger, L.; Ivers, H. The Insomnia Severity Index: Psychometric Indicators to Detect Insomnia Cases and Evaluate Treatment Response. Sleep 2011, 34, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolffs, J.L.; Rogge, R.D.; Wilson, K.G. Disentangling components of flexibility via the hexaflex model: Development and validation of the Multidimensional Psychological Flexibility Inventory (MPFI). Assessment 2018, 25, 458–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; McCracken, L.M. COVID-19 and mental health in the UK: Depression, anxiety and insomnia and their associations with persistent physical symptoms and risk and vulnerability factors. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2024, 63, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, A.; Tran, Y.; Siddall, P.; Wijesuriya, N.; Lovas, J.; Bartrop, R.; Middleton, J. Developing a model of associations between chronic pain, depressive mood, chronic fatigue, and self-efficacy in people with spinal cord injury. J. Pain 2013, 14, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twohig, M.P.; Levin, M.E. Acceptance and commitment therapy as a treatment for anxiety and depression: A review. Psychiatr. Clin. 2017, 40, 751–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Population of England and Wales. 2020. Available online: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/national-and-regional-populations/population-of-england-and-wales/latest (accessed on 1 April 2023).

| Variable | Subcategory | n (%) or Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | No pain | ||

| Gender | Women | 27 (38.6) | 64 (48.1) |

| Men | 42 (60) | 69 (51.9) | |

| Other | 1 (1.4) | 0 | |

| Age | 42.28 (40) | 37.86 (14.06) | |

| Ethnicity | White | 57 (81.4) | 114 (85.7) |

| Black | 5 (7.1) | 13 (9.8) | |

| Mixed | 5 (7.1) | 2 (1.5) | |

| Other | 3 (4.3) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Asian | None | 3 (2.3) | |

| Years of education | 14.71 (2.91) | 15.44 (3.16) | |

| Living area | Suburbs | 49 (70) | 57 (42.8) |

| City | 9 (12.9) | 63 (47.4) | |

| Countryside | 12 (17.1) | 13 (9.8) | |

| Working status | Working full-time | 34 (48.6) | 66 (49.6) |

| Working part-time | 15 (21.4) | 36 (27.1) | |

| Unemployed | 6 (8.6) | 7 (5.3) | |

| Retired | 4 (5.7) | 7 (5.3) | |

| Sick leave | 4 (5.7) | 2 (1.5) | |

| Student | 3 (4.3) | 12 (9.0) | |

| Unpaid work (e.g., volunteer, carer, and homemaker) | 2 (2.9) | 3 (2.3) | |

| Parental leave | 2 (2.9) | 0 | |

| Work change due to COVID-19 | Reduced working hours or workdays | 26 (37.1) | 53 (39.8) |

| No change | 16 (22.9) | 45 (33.8) | |

| Taking sick leave | 10 (14.3) | 4 (3) | |

| Lost job | 7 (10) | 9 (6.8) | |

| Reduced salary | 6 (8.6) | 10 (7.5) | |

| Changed roles or responsibilities | 5 (7.1) | 12 (9) | |

| Healthcare worker for COVID-19 patients | No | 51 (72.9) | 129 (97) |

| Yes | 18 (25.7) | 4 (3) | |

| Economic status | Average | 32 (45.7) | 73 (54.9) |

| Below average | 20 (28.6) | 25 (18.8) | |

| Above average | 9 (12.9) | 27 (20.3) | |

| Much below average | 6 (8.6) | 5 (3.8) | |

| Much above average | 3 (4.3) | 2 (1.5) | |

| Relationship status | Single | 25 (35.7) | 49 (36.8) |

| Married | 20 (28.6) | 55 (41.4) | |

| In a relationship—living apart | 12 (17.1) | 9 (6.8) | |

| In a relationship—cohabitation | 9 (12.9) | 10 (7.5) | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 4 (5.8) | 7 (5.3) | |

| Children under 18 years old | None | 51 (72.9) | 86 (64.7) |

| One | 9 (12.9) | 29 (21.8) | |

| More than one | 9 (12.9) | 16 (12) | |

| Number of people in household | 1 | 16 (22.9) | 36 (27.1) |

| 2 | 18 (25.7) | 26 (19.5) | |

| 3 | 11 (15.7) | 37 (27.8) | |

| 4 | 12 (17.1) | 19 (14.3) | |

| More than 4 | 8 (11.4) | 12 (9) | |

| Having one or more persistent symptoms | 70 (100) | 81 (60.9) | |

| Pain rating: 0–10 | 5.11 (2.20) | ||

| Pain site | Chest | 21 (30) | |

| Lower back | 20 (28.6) | ||

| Lower limbs | 18 (25.7) | ||

| Upper shoulder or upper limbs | 18 (25.7) | ||

| Head or face | 17 (24.3) | ||

| Whole body | 16 (22.9) | ||

| Abdomen | 14 (20) | ||

| Neck | 14 (20) | ||

| Pelvic region | 10 (14.3) | ||

| Other | 5 (7.1) | ||

| All participants n (%) | |||

| Painful persistent physical symptoms | Joint pain | 60 (29.4) | |

| Headache | 51 (25.1) | ||

| Chest pain | 44 (21.6) | ||

| Pins and needles in the limbs | 34 (16.7) | ||

| Sore throat | 28 (13.8) | ||

| Variables | Persistent Pain | n | Mean | SD | t | df | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive symptoms | Yes | 70 | 14.90 | 5.85 | 8.33 | 201 | <0.001 | 1.23 |

| No | 133 | 7.62 | 5.95 | |||||

| Anxiety | Yes | 70 | 11.39 | 5.63 | 7.18 | 201 | <0.001 | 1.01 |

| No | 133 | 5.83 | 5.02 | |||||

| Insomnia | Yes | 70 | 14.26 | 6.80 | 6.22 | 201 | <0.001 | 0.92 |

| No | 133 | 8.54 | 5.91 | |||||

| Psychological flexibility | Yes | 70 | 3.34 | 0.85 | 1.14 | 201 | 0.255 | 0.17 |

| No | 133 | 3.5 | 0.96 | |||||

| Psychological inflexibility | Yes | 66 | 3.31 | 0.83 | 2.86 | 189 | 0.005 | 0.44 |

| No | 125 | 2.95 | 0.83 | |||||

| Total persistent symptoms | Yes | 70 | 9.57 | 6.12 | 7.34 | 105.38 | <0.001 | 1.21 |

| No | 133 | 3.55 | 4.28 |

| Participants With Persistent Pain | Participants Without Persistent Pain | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Anxiety | Insomnia | Persistent Physical Symptoms | Depression | Anxiety | Insomnia | Persistent Physical Symptoms | |

| Persistent physical symptoms | 0.38 ** | 0.26 * | 0.21 ** | 0.45 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.52 *** | ||

| Total psychological flexibility | −0.31 ** | −0.22 | −0.13 | −0.22 | −0.20 * | −0.23 ** | −0.15 | 0.11 |

| Total psychological inflexibility | 0.63 *** | 0.63 *** | 0.46 *** | −0.003 | 0.51 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.19 * |

| Acceptance | −0.22 | −0.10 | −0.13 | −0.31 ** | 0.002 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.11 |

| Present moment awareness | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.06 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.08 | 0.15 |

| Self-as-context | −0.29 * | −0.23 | −0.12 | −0.09 | −0.22 * | −0.25 ** | −0.16 | 0.07 |

| Defusion | −0.37 ** | −0.37 ** | −0.14 | −0.24 * | −0.29 *** | −0.36 *** | −0.29 *** | −0.01 |

| Values | −0.18 | −0.08 | −0.07 | −0.16 | −0.14 | −0.16 | −0.09 | 0.15 |

| Committed action | −0.39 *** | −0.31 ** | −0.21 | −0.24 * | −0.25 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.17 | 0.10 |

| Experiential avoidance | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.17 | −0.05 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.16 |

| Lack of contact with present moment | 0.28 * | 0.30 * | 0.27 * | −0.05 | 0.27 ** | 0.29 *** | 0.21 * | 0.05 |

| Self-as-content | 0.51 *** | 0.64 *** | 0.39 ** | −0.11 | 0.43 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.13 |

| Fusion | 0.67 *** | 0.71 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.13 | 0.55 *** | 0.60 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.28 ** |

| Lack of contact with values | 0.54 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.04 | 0.47 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.10 |

| Inaction | 0.69 *** | 0.67 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.02 | 0.56 *** | 0.60 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.17 |

| Psychological Flexibility | Estimate/Effect/Path Coefficient | p |

|---|---|---|

| Low | 0.11 | 0.55 |

| Medium | 0.45 | <0.01 |

| High | 0.75 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, L.; McCracken, L.M. The Association Between COVID-19-Related Persistent Symptoms, Psychological Flexibility, and General Mental Health Among People With and Without Persistent Pain in the UK. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15070119

Yu L, McCracken LM. The Association Between COVID-19-Related Persistent Symptoms, Psychological Flexibility, and General Mental Health Among People With and Without Persistent Pain in the UK. Clinics and Practice. 2025; 15(7):119. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15070119

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Lin, and Lance M. McCracken. 2025. "The Association Between COVID-19-Related Persistent Symptoms, Psychological Flexibility, and General Mental Health Among People With and Without Persistent Pain in the UK" Clinics and Practice 15, no. 7: 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15070119

APA StyleYu, L., & McCracken, L. M. (2025). The Association Between COVID-19-Related Persistent Symptoms, Psychological Flexibility, and General Mental Health Among People With and Without Persistent Pain in the UK. Clinics and Practice, 15(7), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15070119