Where Do We Stand in the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis Ahead of EULAR/ACR 2025?

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Pathophysiology and Causes of Rheumatoid Arthritis

1.2. Clinical Signs and Symptoms

1.3. Diagnosis of Rheumatoid Arthritis

2. Materials and Methods

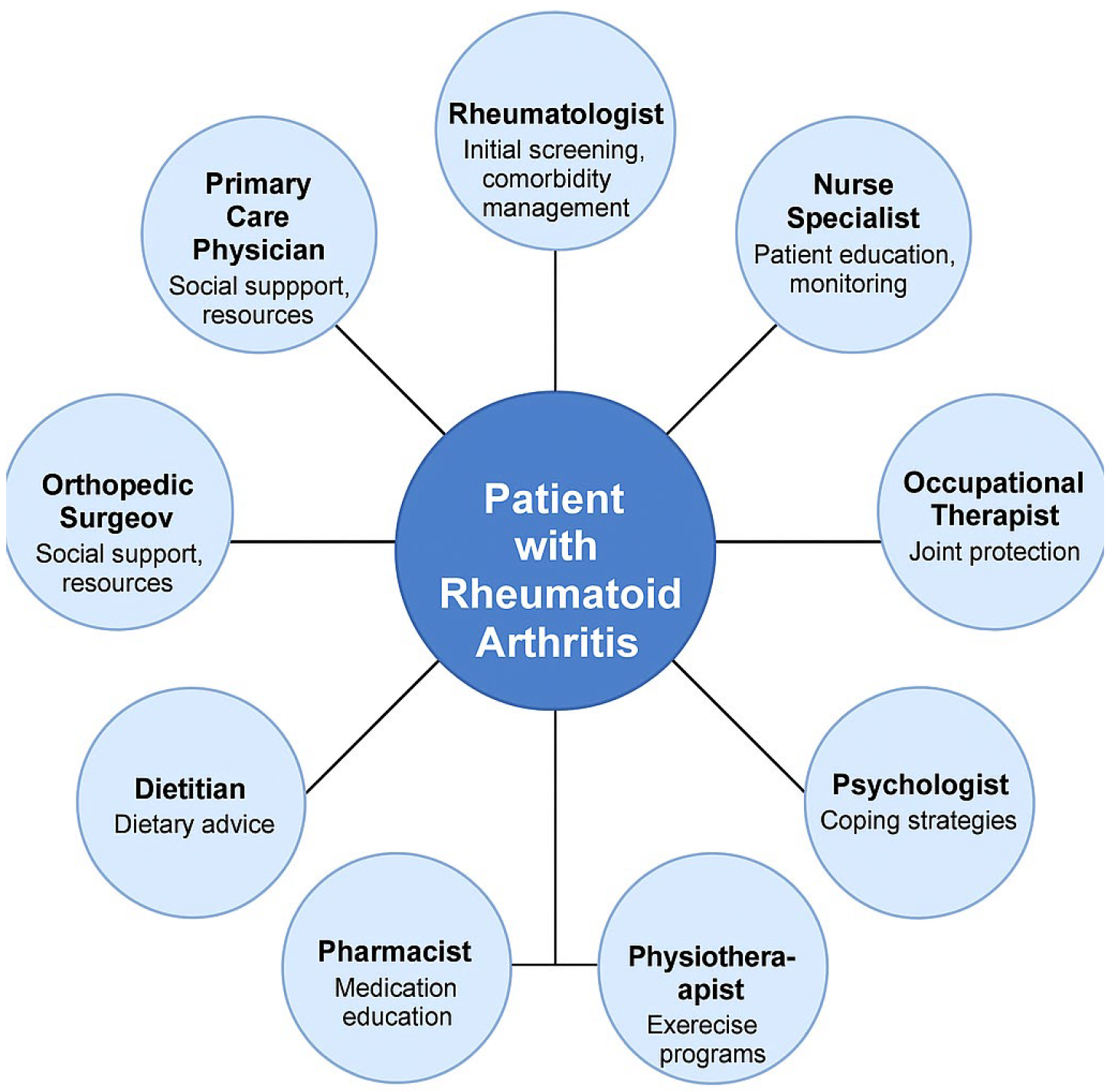

- Pharmacological interventions, including NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and DMARDs, within a collaborative framework.

- Non-pharmacological strategies, such as physiotherapy, dietary interventions, and psychosocial support.

- The role of a multidisciplinary team in enhancing patient outcomes, including the integration of rheumatologists, general practitioners, psychologists, and rehabilitation specialists.

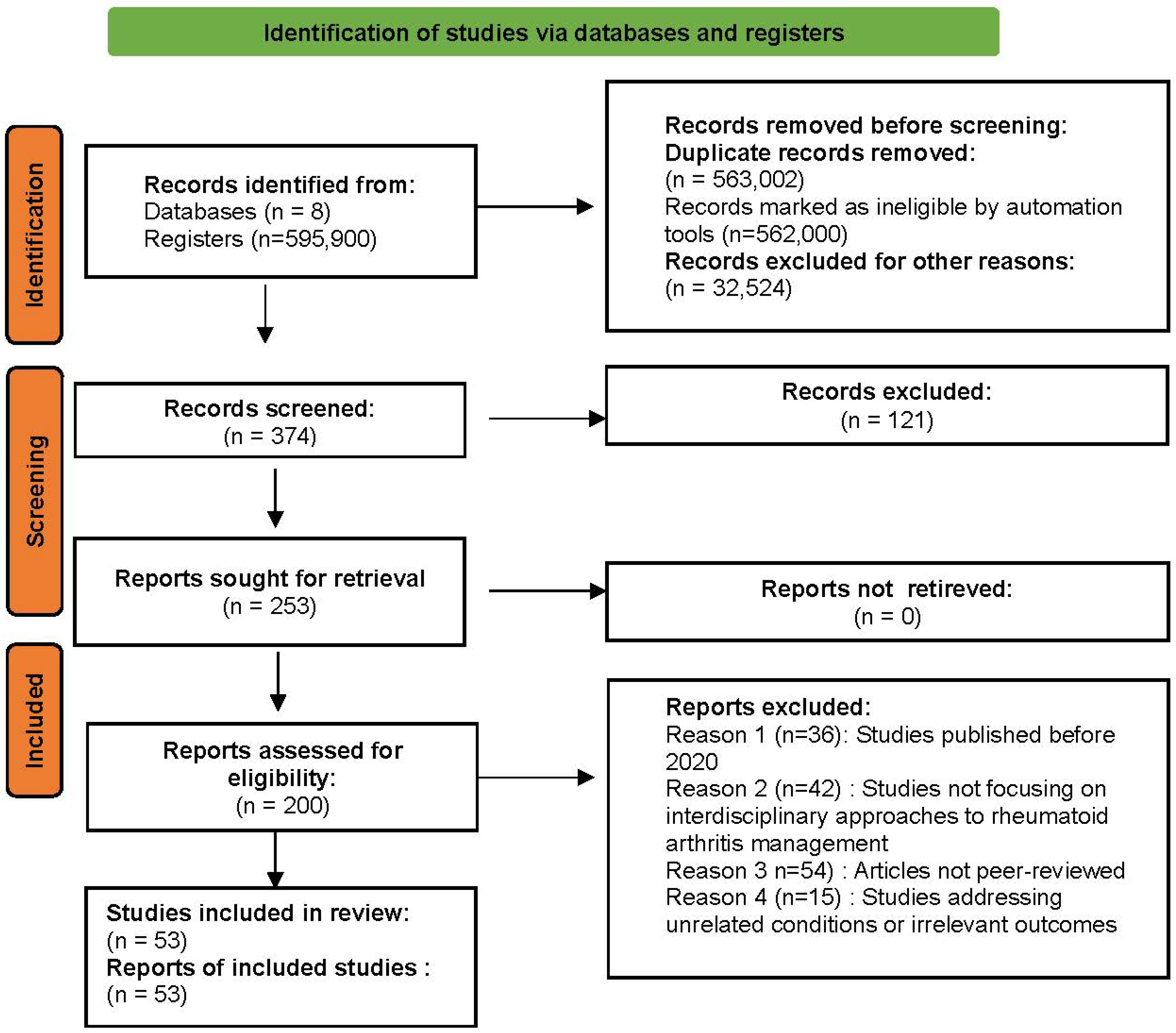

2.1. Approach to Identifying Relevant Articles

2.2. Eligibility Criteria for Study Selection

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Pharmacological treatments (NSAIDs, corticosteroids, DMARDs) within a multidisciplinary care framework.

- Monitoring tools, such as inflammatory markers (e.g., CRP, ESR) and imaging techniques (e.g., ultrasound, MRI).

- Non-pharmacological interventions, including physiotherapy, dietary strategies, and psychosocial support.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Studies not adhering to PRISMA guidelines, as compliance is critical for methodological rigor.

- Case studies without generalisable findings or lacking a clear interdisciplinary focus.

2.2.3. Selection Process

2.3. Risk of Bias and Evidence Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Selected Studies

3.2. The Role of NSAIDs in the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis

3.3. The Role of Corticosteroids in the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis

3.4. Comparison Between Conventional and Biologic DMARDs in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis

3.5. Monitoring the Response to Rheumatoid Arthritis Treatment

3.6. The Interdisciplinary Approach in Treatment and Management

4. Discussion

5. Future Perspectives in the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis

5.1. Expansion of Digital Rehabilitation Platforms

5.2. Virtual and Augmented Reality in Personalised Therapy

5.3. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Clinical Decision Making

5.4. Integration of Personalised Nutrition into Routine Care

5.5. Towards an Interdisciplinary, Patient-Centred Model

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Poznyak, A.V.; Kirichenko, T.V.; Beloyartsev, D.F.; Churov, A.V.; Kovyanova, T.I.; Starodubtseva, I.A.; Sukhorukov, V.N.; Antonov, S.A.; Orekhov, A.N. Rheumatoid Arthritis: What Inflammation Do We Face? J. Mol. Pathol. 2024, 5, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-J.; Anzaghe, M.; Schülke, S. Update on the Pathomechanism, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Cells 2020, 9, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundas, A.; Contreras, I.; Mujahid, O.; Beneyto, A.; Vehi, J. The Effects of Environmental Factors on General Human Health: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bo, M.; Jasemi, S.; Uras, G.; Erre, G.L.; Passiu, G.; Sechi, L.A. Role of Infections in the Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Focus on Mycobacteria. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finckh, A.; Gilbert, B.; Hodkinson, B.; Bae, S.C.; Thomas, R.; Deane, K.D.; Lauper, K. Global Epidemiology of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2022, 18, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, C.; Greco, M.; Munir, A.; Musarò, D.; Quarta, S.; Massaro, M.; Lionetto, M.G.; Maffia, M. Osteoarthritis: Insights into Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, Therapeutic Avenues, and the Potential of Natural Extracts. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 4063–4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, L.; Aurrecoechea, E.; García de Yébenes, M.J. Tailoring Rheumatoid Arthritis Treatment through a Sex and Gender Lens. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhal, L.; Lwin, M.N.; Holroyd, C.; Edwards, C.J. Rheumatoid Arthritis in the Elderly: Characteristics and Treatment Considerations. Autoimmun. Rev. 2020, 19, 102528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbodo, J.O.; Arazu, A.V.; Iguh, T.C.; Onwodi, N.J.; Ezike, T.C. Volatile organic compounds: A proinflammatory activator in autoimmune diseases. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 928379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celen, H.; Dens, A.C.; Ronsmans, S.; Michiels, S.; De Langhe, E. Airborne pollutants as potential triggers of systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases: A narrative review. Acta Clin. Belg. 2022, 77, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figus, F.A.; Piga, M.; Azzolin, I.; McConnell, R.; Iagnocco, A. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Extra-Articular Manifestations and Comorbidities. Autoimmun. Rev. 2021, 20, 102776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roodenrijs, N.M.; van der Goes, M.C.; Welsing, P.M.; Tekstra, J.; Lafeber, F.P.; Jacobs, J.W.; van Laar, J.M. Difficult-to-Treat Rheumatoid Arthritis: Contributing Factors and Burden of Disease. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 3778–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, A.L.; Payandeh, Z.; Mohammadkhani, N.; Mubarak, S.M.; Zakeri, A.; Alagheband Bahrami, A.; Shakibaei, M. Recent Advances in Understanding the Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis: New Treatment Strategies. Cells 2021, 10, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Mohan, K.; Muzammil, S.; Alam, M.A.; Khayyam, K.U. Current Prospects in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Pathophysiology, Genetics, and Treatments. Recent Adv. Anti-Infect. Drug Discov. 2024, 19, 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberemok, V.V.; Andreeva, O.; Laikova, K.; Alieva, E.; Temirova, Z. Rheumatoid Arthritis Has Won the Battle but Not the War: How Many Joints Will We Save Tomorrow? Medicina 2023, 59, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Kwon, E.-J.; Lee, J.J. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Pathogenic Roles of Diverse Immune Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Gao, J.; Kang, J.; Wang, X.; Niu, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L. B Cells in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Treatment Prospects. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 750753. [Google Scholar]

- Kostara, M.; Chondrou, V.; Sgourou, A.; Douros, K.; Tsabouri, S. HLA Polymorphisms and Food Allergy Predisposition. J. Pediatr. Genet. 2020, 9, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romão, V.C.; Fonseca, J.E. Etiology and Risk Factors for Rheumatoid Arthritis: A State-of-the-Art Review. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 689698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arleevskaya, M.; Takha, E.; Petrov, S.; Kazarian, G.; Renaudineau, Y.; Brooks, W.; Larionova, R.; Korovina, M.; Valeeva, A.; Shuralev, E.; et al. Interplay of Environmental, Individual and Genetic Factors in Rheumatoid Arthritis Provocation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Zhou, C.; Nandakumar, K.S. Molecular and Cellular Pathways Contributing to Joint Damage in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 3830212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Seny, D.; Baiwir, D.; Bianchi, E.; Cobraiville, G.; Deroyer, C.; Poulet, C.; Malaise, O.; Paulissen, G.; Kaiser, M.-J.; Hauzeur, J.-P.; et al. New Proteins Contributing to Immune Cell Infiltration and Pannus Formation of Synovial Membrane from Arthritis Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemcansky, J.; Bradna, P.; Kolarcikova, V. Rheumatic Diseases. In Ocular Manifestations of Systemic Diseases; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 207–265. [Google Scholar]

- Radu, A.-F.; Bungau, S.G. Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis: An Overview. Cells 2021, 10, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, D.P. Clinical Manifestations of Rheumatoid Arthritis, Including Comorbidities, Complications, and Long-Term Follow-Up. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2024, 38, 102020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquhoun, M.; Gulati, M.; Farah, Z.; Mouyis, M. Clinical Features of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Medicine 2022, 50, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumathi, L.; Pichaivel, M.; Kandasamy, T. A Review on Rheumatoid Arthritis. Asian J. Pharm. Res. Dev. 2022, 10, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-W.; Suh, C.-H. Systemic Manifestations and Complications in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, B. Subcutaneous Nodules as Manifestations of Systemic Disease. Rheumato 2024, 4, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, A.T.; Odeyinka, O.; Alhashimi, R.; Thoota, S.; Ashok, T.; Palyam, V.; Sange, I. Rheumatoid Arthritis and Associated Lung Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e21914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hysa, E.; Cutolo, C.A.; Gotelli, E.; Paolino, S.; Cimmino, M.A.; Pacini, G.; Cutolo, M. Ocular Microvascular Damage in Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases: The Pathophysiological Role of the Immune System. Autoimmun. Rev. 2021, 20, 102796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietschmann, P.; Butylina, M.; Kerschan-Schindl, K.; Sipos, W. Mechanisms of Systemic Osteoporosis in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, P.C.; Atzeni, F.; Balsa, A.; Gossec, L.; Müller-Ladner, U.; Pope, J. The Key Comorbidities in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elangovan, S.; Tan, Y.K. The Role of Musculoskeletal Ultrasound Imaging in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2020, 46, 1841–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rönnelid, J.; Turesson, C.; Kastbom, A. Autoantibodies in Rheumatoid Arthritis—Laboratory and Clinical Perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 685312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahali, F.Z.; Tarmidi, M.; Hazime, R.; Admou, B. Clinical Significance of Anti-Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide (Anti-CCP) Antibodies in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Literature Review. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2023, 5, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, E.B.; Song, Y.W.; Park, J.K. Profile of Common Inflammatory Markers in Treatment-Naïve Patients with Systemic Rheumatic Diseases. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 39, 2899–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Weyand, C.M.; Goronzy, J.J. The Immunology of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, M.N.; Leiguez, E.; Gutiérrez, J.M.; Rucavado, A.; Markus, R.P.; Marçola, M.; Fernandes, C.M. A Representative Metalloprotease Induces PGE2 Synthesis in Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes via the NF-κB/COX-2 Pathway with Amplification by IL-1β and the EP4 Receptor. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemantsverdriet, E.; Dakkak, Y.J.; Burgers, L.E.; Bonte-Mineur, F.; Steup-Beekman, G.M.; van der Kooij, S.M.; van der Helm-van Mil, A.H. TREAT Early Arthralgia to Reverse or Limit Impending Exacerbation to Rheumatoid Arthritis (TREAT EARLIER): A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial Protocol. Trials 2020, 21, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Malah, A.A.; Gineinah, M.M.; Deb, P.K.; Khayyat, A.N.; Bansal, M.; Venugopala, K.N.; Aljahdali, A.S. Selective COX-2 Inhibitors: Road from Success to Controversy and the Quest for Repurposing. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piplani, S.; Jelic, V.; Johnson, A.; Shah, U.; Kolli, S.; Kong, S.; Jain, P. Prevalence, Causes and Outcomes of Acute Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mediterr. J. Rheumatol. 2024, 35, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, S.U.; Chopra, V.S.; Dar, M.A.; Maqbool, M.; Qadrie, Z.; Qadir, A. Advancing Rheumatic Disease Treatment: A Journey Towards Better Lives. Open Health 2024, 5, 20230040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alivernini, S.; Firestein, G.S.; McInnes, I.B. The Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Immunity 2022, 55, 2255–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, P.; Verma, S.; Surbhi; Ganguly, N.K.; Chaturvedi, V.; Mittal, S.A. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Advances in Treatment Strategies. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2023, 478, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Pratt, A.G.; Hyrich, K.L. Therapeutic Advances in Rheumatoid Arthritis. BMJ 2024, 384, e075658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quatrini, L.; Ugolini, S. New Insights into the Cell- and Tissue-Specificity of Glucocorticoid Actions. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M.; Daniyal, M.; Sultana, S.; Owais, A.; Akhtar, N.; Zahid, R.; Thiruvengadam, M. Traditional and Modern Management Strategies for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2021, 512, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, S.I.; Rosas, H.G.; Gorbachova, T. Local and Systemic Side Effects of Corticosteroid Injections for Musculoskeletal Indications. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2024, 222, e2330458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutolo, M.; Shoenfeld, Y.; Bogdanos, D.P.; Gotelli, E.; Salvato, M.; Gunkl-Tóth, L.; Nagy, G. To Treat or Not to Treat Rheumatoid Arthritis with Glucocorticoids? A Reheated Debate. Autoimmun. Rev. 2024, 23, 103437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crossfield, S.S.; Buch, M.H.; Baxter, P.; Kingsbury, S.R.; Pujades-Rodriguez, M.; Conaghan, P.G. Changes in the Pharmacological Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis over Two Decades. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 4141–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floris, A.; Piga, M.; Chessa, E.; Congia, M.; Erre, G.L.; Angioni, M.M.; Cauli, A. Long-Term Glucocorticoid Treatment and High Relapse Rate Remain Unresolved Issues in the Real-Life Management of Polymyalgia Rheumatica: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2022, 41, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendling, D.; Al Tabaa, O.; Chevet, B.; Fakih, O.; Ghossan, R.; Hecquet, S.; Devauchelle-Pensec, V. Recommendations of the French Society of Rheumatology for the Management in Current Practice of Patients with Polymyalgia Rheumatica. Jt. Bone Spine 2024, 91, 105730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrid, R.B.; Bouchmaa, N.; Ainani, H.; El Fatimy, R.; Malka, G.; Mazini, L. Anti-Rheumatoid Drugs Advancements: New Insights into the Molecular Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 151, 113126. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Pedrera, C.; Barbarroja, N.; Patiño-Trives, A.M.; Luque-Tévar, M.; Collantes-Estevez, E.; Escudero-Contreras, A.; Pérez-Sánchez, C. Effects of Biological Therapies on Molecular Features of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venetsanopoulou, A.I.; Voulgari, P.V.; Drosos, A.A. Advances in Non-Biological Drugs for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2024, 25, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubiel-Braszczok, B.; Nowak, K.; Owczarek, A.; Engelmann, M.; Gumkowska-Sroka, O.; Kotyla, P.J. Differential Impact of Biologic Therapy on Heart Function Biomarkers in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients: Observational Study on Etanercept, Adalimumab, and Tocilizumab. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2022, 28, 2029–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, F.; Geng, S.; Wang, X.; Gu, L.; Lang, Y.; Ye, S. Methotrexate (MTX) Plus Hydroxychloroquine Versus MTX Plus Leflunomide in Patients with MTX-Resistant Active Rheumatoid Arthritis: A 2-Year Cohort Study in Real World. J. Inflamm. Res. 2020, 13, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Fu, X.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Huang, Y.; Liang, C. Promising Therapeutic Targets for Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 686155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koźmiński, P.; Halik, P.K.; Chesori, R.; Gniazdowska, E. Overview of Dual-Acting Drug Methotrexate in Different Neurological Diseases, Autoimmune Pathologies and Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerschbaumer, A.; Sepriano, A.; Smolen, J.S.; van der Heijde, D.; Dougados, M.; van Vollenhoven, R.; Landewé, R. Efficacy of Pharmacological Treatment in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Literature Research Informing the 2019 Update of the EULAR Recommendations for Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 744–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Promelle, V.; Goeb, V.; Gueudry, J. Rheumatoid Arthritis Associated Episcleritis and Scleritis: An Update on Treatment Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysler, E.; Caubet, M.; Lizarraga, A. Current and Emerging DMARDs for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Open Access Rheumatol. Res. Rev. 2021, 13, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Sleen, Y.; van der Geest, K.S.; Huckriede, A.L.; van Baarle, D.; Brouwer, E. Effect of DMARDs on the Immunogenicity of Vaccines. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2023, 19, 560–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, C.L.; Adams, D.; Assis, D.N.; Kerkar, N.; Manns, M.P.; Mayo, M.J.; Czaja, A.J. Diagnosis and Management of Autoimmune Hepatitis in Adults and Children: 2019 Practice Guidance and Guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2020, 72, 671–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.M.; Chen, D.Y. Infection Risk in Patients Undergoing Treatment for Inflammatory Arthritis: Non-Biologics versus Biologics. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 16, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dammacco, R.; Guerriero, S.; Alessio, G.; Dammacco, F. Natural and Iatrogenic Ocular Manifestations of Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review. Int. Ophthalmol. 2022, 42, 689–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosos, A.A.; Pelechas, E.; Kaltsonoudis, E.; Voulgari, P.V. Therapeutic Options and Cost-Effectiveness for Rheumatoid Arthritis Treatment. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2020, 22, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolen, J.S.; Landewé, R.B.; Bijlsma, J.W.; Burmester, G.R.; Dougados, M.; Kerschbaumer, A.; Van Der Heijde, D. EULAR Recommendations for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis with Synthetic and Biological Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs: 2019 Update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarroja, N.; Ruiz-Ponce, M.; Cuesta-López, L.; Perez-Sanchez, C.; Lopez-Pedrera, C.; Arias-de La Rosa, I.; Collantes-Estévez, E. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Inflammatory Arthritis: Relationship with Cardiovascular Risk. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 997270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepriano, A.; Kerschbaumer, A.; Smolen, J.S.; Van Der Heijde, D.; Dougados, M.; Van Vollenhoven, R.; Landewé, R. Safety of Synthetic and Biological DMARDs: A Systematic Literature Review Informing the 2019 Update of the EULAR Recommendations for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 760–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cola, I.; Ruscitti, P. The Latest Advances in the Use of Biological DMARDs to Treat Still’s Disease. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2024, 24, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, P.; Marcal, B.; Button, P.; Truman, M.; Bird, P.; Griffiths, H.; Littlejohn, G. Reasons for Biologic and Targeted Synthetic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drug Cessation and Persistence of Second-Line Treatment in a Rheumatoid Arthritis Dataset. J. Rheumatol. 2020, 47, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherkatolabbasieh, H.; Firouzi, M.; Shafizadeh, S. Evaluation of Platelet Count, Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate and C-Reactive Protein Levels in Paediatric Patients with Inflammatory and Infectious Disease. New Microbes New Infect. 2020, 37, 100725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhafiz, D.; Baker, T.; Glascow, D.A.; Abdelhafiz, A. Biomarkers for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis—A Systematic Review. Postgrad. Med. 2023, 135, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, J.E.; Choy, E.H. C-Reactive Protein and Implications in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Associated Comorbidities. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2021, 51, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targońska-Stępniak, B.; Zwolak, R.; Piotrowski, M.; Grzechnik, K.; Majdan, M. The Relationship between Hematological Markers of Systemic Inflammation (Neutrophil-To-Lymphocyte, Platelet-To-Lymphocyte, Lymphocyte-To-Monocyte Ratios) and Ultrasound Disease Activity Parameters in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, N.; Ali, A.; Ayub, M. High Quantitative CRP and Low Albumin as Markers of Disease Activity in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Health Rehabil. Res. 2024, 4, 1073–1077. [Google Scholar]

- Conforti, A.; Di Cola, I.; Pavlych, V.; Ruscitti, P.; Berardicurti, O.; Ursini, F.; Cipriani, P. Beyond the Joints: The Extra-Articular Manifestations in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2021, 20, 102735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, M.; Shah, S.A.A.; ur Rehman, Z. A Review of Arthritis Diagnosis Techniques in Artificial Intelligence Era: Current Trends and Research Challenges. Neurosci. Inform. 2022, 2, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, J.S.; Omar, I.; Mar, W.; Kauser, A.S.; Mlady, G.W.; Taljanovic, M. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Rheumatological Diseases. Pol. J. Radiol. 2022, 87, e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gukova, X.; Hazlewood, G.S.; Arbillaga, H.; MacMullan, P.; Zimmermann, G.L.; Barnabe, C.; Barber, C.E. Development of an Interdisciplinary Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Care Pathway. BMC Rheumatol. 2022, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech, B.; Primdahl, J.; van Tubergen, A.; Voshaar, M.; Zangi, H.A.; Barbosa, L.; van Eijk-Hustings, Y. 2018 Update of the EULAR Recommendations for the Role of the Nurse in the Management of Chronic Inflammatory Arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, A.; Patwari, S.; Pansari, M.; Padhan, S. Navigating Pain in Rheumatology: A Physiotherapy-Centric Review on Non-Pharmacological Pain Management Strategies. Cureus 2023, 15, e38705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikiphorou, E.; Philippou, E. Nutrition and Its Role in Prevention and Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2023, 22, 103333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, Z.; Szigedi, E.; Takács, S.; Császár-Nagy, N. The Effectiveness of Psychological Interventions for Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Life 2023, 13, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghele, M.; Marina, V.; Moscu, C.A.; Dragomir, L.; Anghele, A.D.; Lescai, A.M. Emotional Distress in Patients Following Polytrauma. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2023, 16, 1161–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Ludovico, A.; La Bella, S.; Di Donato, G.; Felt, J.; Chiarelli, F.; Breda, L. The Benefits of Physical Therapy in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Rheumatol. Int. 2023, 43, 1563–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, J.P.; Rossiter, L.; Fenerty, V.; Leese, J.; Adams, J.; Hammond, A.; Backman, C.L. The Impact of Occupational Therapy on the Self-Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2024, 6, 214–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brignon, M.; Vioulac, C.; Boujut, E.; Delannoy, C.; Beauvais, C.; Kivits, J.; Rat, A.C. Patients and Relatives Coping with Inflammatory Arthritis: Care Teamwork. Health Expect. 2020, 23, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacIver, A.; Hollinger, H.; Carolan, C. Tele-Health Interventions to Support Self-Management in Adults with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review. Rheumatol. Int. 2021, 41, 1399–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dervisevic, A.; Fajkic, A.; Jahic, E.; Dervisevic, L.; Ajanovic, Z.; Ademovic, E.; Zaciragic, A. Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index in Evaluation of Inflammation in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Medeni. Med. J. 2024, 39, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cierpiak, K.; Wityk, P.; Kosowska, M.; Sokołowski, P.; Talaśka, T.; Gierowski, J.; Szczerska, M. C-Reactive Protein (CRP) Evaluation in Human Urine Using Optical Sensor Supported by Machine Learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhao, D.; Qin, R.; Zhao, X.; Huo, Z.; Li, P. Associations of Three Differential White Blood Cell Counts, Platelet Counts, and Their Derived Inflammatory Indices with Cancer-Related Fatigue in Patients with Breast Cancer Undergoing Chemotherapy. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, G.A.; de Oliveira, L.C.; Wiegert, E.V.M.; Calixto-Lima, L.; da Costa Cunha, G.; Peres, W.A.F. Prognostic Risk Stratification Using C-Reactive Protein, Albumin, and Associated Inflammatory Biomarkers in Patients with Advanced Cancer in Palliative Care. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2024, 51, 101115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, R.G. New Developments in Imaging in Crystalline Arthritis. Rheum. Dis. Clin. 2024, 50, 683–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, V.; Tripathi, D.; Sharma, S.; Purohit, A.; Singh, P. Phytomedicine Meets Nanotechnology: A Cellular Approach to Rheumatoid Arthritis Treatment. Nano TransMed 2024, 3, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, C.; Buttgereit, F.; Combe, B. Glucocorticoids in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Current Status and Future Studies. RMD Open 2020, 6, e000536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.C.; Kao, T.E.; Chen, C.L.; Lin, Y.C.; Hwang, D.K.; Hwang, Y.S.; Sheu, S.J. Use of Corticosteroids in Non-Infectious Uveitis—Expert Consensus in Taiwan. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2352019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov-Dolijanovic, S.; Bogojevic, M.; Nozica-Radulovic, T.; Radunovic, G.; Mujovic, N. Elderly-Onset Rheumatoid Arthritis: Characteristics and Treatment Options. Medicina 2023, 59, 1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Tiwary, N.; Sharma, N.; Behl, T.; Antil, A.; Anwer, M.K.; Ramniwas, S.; Sachdeva, M.; Elossaily, G.M.; Gulati, M.; et al. Integrating Nanotechnological Advancements of Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs into Rheumatoid Arthritis Management. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inchingolo, F.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Fatone, M.C.; Avantario, P.; Del Vecchio, G.; Pezzolla, C.; Mancini, A.; Galante, E.; Palermo, A.; Inchingolo, A.D.; et al. Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis in Primary Care: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andronache, I.-T.; Șuța, V.-C.; Șuța, M.; Ciocodei, S.-L.; Vlădăreanu, L.; Nicoară, A.D.; Arghir, O.C. Better Safe than Sorry: Rheumatoid Arthritis, Interstitial Lung Disease, and Medication—A Narrative Review. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedeković, D.; Bošnjak, I.; Šarić, S.; Kirner, D.; Novak, S. Role of Inflammatory Cytokines in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Development of Atherosclerosis: A Review. Medicina 2023, 59, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aspect | Details | References |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Control inflammation, prevent joint destruction, and maintain patient functionality. | [40] |

| Role of NSAIDs | Reduce pain and joint stiffness by inhibiting COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes, decreasing the production of prostaglandins involved in inflammation and pain. | [41] |

| Clinical Use | Frequently used in the early stages of the disease or during flare-ups. Recommended as symptomatic treatment without impact on disease progression. | [42] |

| Choice of NSAID | Depends on the patient’s safety profile, medical history, and individual response. COX-2 selective inhibitors (e.g., celecoxib) pose fewer gastrointestinal risks. | [43] |

| Common Side Effects | Gastric ulcers, renal insufficiency, and cardiovascular risks, particularly with long-term use. | [44] |

| Monitoring Required | Careful monitoring to prevent complications and integration into a broader therapeutic plan, including DMARDs. | [45] |

| Limitations | Do not influence long-term disease progression, being used solely for symptomatic relief. | [46] |

| Benefits | Rapid control of inflammatory symptoms and improved quality of life during critical phases of the disease. | [47] |

| Importance in Treatment | Part of an integrated therapeutic plan, used judiciously to balance benefits and risks. | [48] |

| Aspect | Details | References |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Mimic the action of glucocorticoids produced by the adrenal glands, exerting anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects. Inhibit the production of inflammatory cytokines and reduce immune cell activity. | [49] |

| Clinical Use | Rapidly control inflammation and alleviate acute symptoms, particularly useful during disease flares or as “bridging therapy” before the effects of DMARDs take hold. | [24] |

| Benefits | Quickly reduce pain, swelling, and joint stiffness. Slow joint damage progression in early stages and help maintain inflammation control in severe forms. | [50] |

| Administration | Low doses for long-term inflammation control or higher doses for short-term intervention during acute crises. | [51] |

| Adverse Effects | Osteoporosis, increased blood pressure, steroid-induced diabetes, weight gain, higher infection risk, Cushing’s syndrome, skin fragility, and muscle weakness. | [52] |

| Monitoring Required | Dose adjustments to the minimum necessary. Monitor side effects and prevent osteoporosis using calcium, vitamin D supplementation, or anti-resorptive therapy. | [53] |

| Limitations | Significant adverse effects limit long-term use. Requires careful management to minimise risks. | [54] |

| Role in Treatment | A valuable tool for rapid inflammation control, particularly in severe cases, but should be used responsibly as part of a comprehensive therapeutic plan. | [55] |

| Aspect | Conventional DMARDs | Biologic DMARDs | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Conventional drugs that modulate the immune response to reduce inflammation and slow disease progression. | Biologic agents that specifically target molecules or cells involved in the inflammatory immune response. | [56,57] |

| Examples | Methotrexate, Sulfasalazine, Hydroxychloroquine, Leflunomide. | Infliximab, Adalimumab, Tocilizumab, Etanercept. | [58,59] |

| Mechanism of Action | Inhibit immune cell proliferation and reduce the synthesis of inflammatory cytokines. | Block specific immune targets, such as TNF-α, interleukins, or other inflammatory proteins. | [60,61] |

| Efficacy | Gold standard for rheumatoid arthritis treatment (e.g., Methotrexate). Can be used as monotherapy or in combination with other drugs. | Highly effective, particularly for patients unresponsive to conventional DMARDs. | [62,63] |

| Route of Administration | Usually, oral. | Typically, injectable or via infusion. Recently, some synthetic biologic therapies (e.g., JAK inhibitors) are available orally. | [64,65] |

| Time to Effect | Requires weeks or months to achieve maximum effect. | Faster clinical response compared to conventional DMARDs. | [57,66] |

| Risks and Side Effects | Hepatotoxicity, bone marrow suppression, and allergic reactions. Frequent monitoring of liver function and blood counts required. | Increased risk of severe infections, including latent tuberculosis. Injection site or secondary autoimmune reactions may occur. | [67,68,69] |

| Costs | Lower costs, accessible in most healthcare systems. | High costs, usually reserved for severe cases or those unresponsive to conventional DMARDs. | [70,71] |

| Monitoring | Requires liver function tests and blood counts. | Regular evaluations for infections and adverse reactions needed. | [72,73] |

| Benefits | First-line treatment, effective for most patients. | Second-line treatment with high efficacy in refractory cases. | [74,75] |

| Limitations | May require combination therapy for optimal response. Slower onset of action. | High costs and increased risk of severe side effects. | [2,76] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vlad, A.L.; Popazu, C.; Lescai, A.-M.; Voinescu, D.C.; Baltă, A.A.Ș. Where Do We Stand in the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis Ahead of EULAR/ACR 2025? Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15060103

Vlad AL, Popazu C, Lescai A-M, Voinescu DC, Baltă AAȘ. Where Do We Stand in the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis Ahead of EULAR/ACR 2025? Clinics and Practice. 2025; 15(6):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15060103

Chicago/Turabian StyleVlad, Adriana Liliana, Corina Popazu, Alina-Maria Lescai, Doina Carina Voinescu, and Alexia Anastasia Ștefania Baltă. 2025. "Where Do We Stand in the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis Ahead of EULAR/ACR 2025?" Clinics and Practice 15, no. 6: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15060103

APA StyleVlad, A. L., Popazu, C., Lescai, A.-M., Voinescu, D. C., & Baltă, A. A. Ș. (2025). Where Do We Stand in the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis Ahead of EULAR/ACR 2025? Clinics and Practice, 15(6), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15060103