Caring-Healing Modalities for Emotional Distress and Resilience in Persons with Cancer: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (a)

- What are the CHMs’ active ingredients?

- (b)

- What are the CHMs’ nonspecific elements?

- (c)

- What is the mode of delivery (medium and format) for identified CHMs?

- (d)

- What is the structure/approach of the identified CHMs and their components?

- (e)

- What is the dose of CHMs identified in the literature?

- (f)

- What is the duration and frequency of implemented CHMs?

- (g)

- What other outcomes besides resilience, depression, and anxiety have been assessed in the located CHMs?

- (h)

- What instruments have been used to evaluate the outcomes assessed in the located studies? [23]

2. Materials and Methods

Protocol Deviation

3. Results

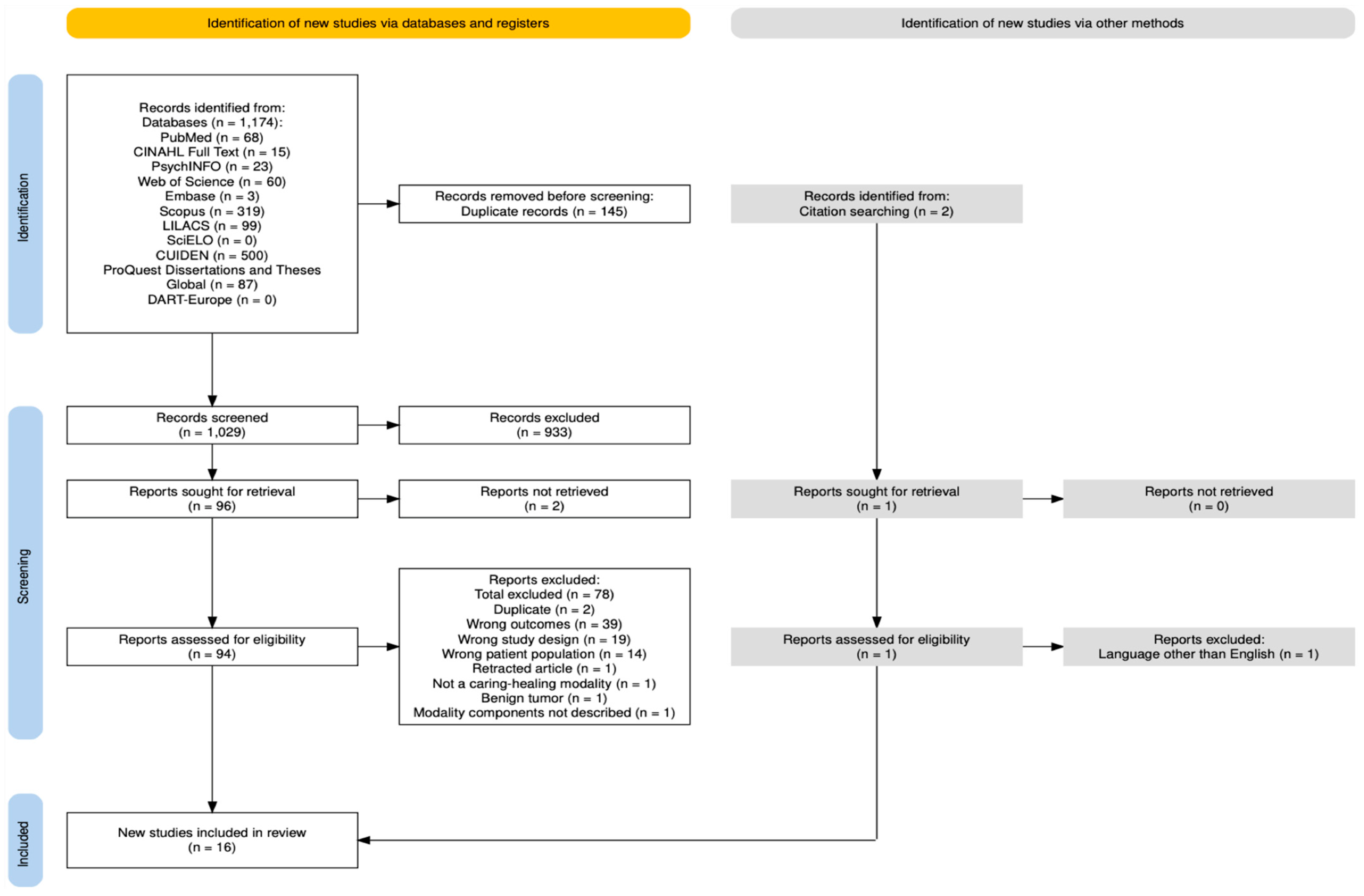

3.1. Source of Evidence Inclusion

3.2. Characteristics of Included Sources of Evidence

3.3. Review Findings

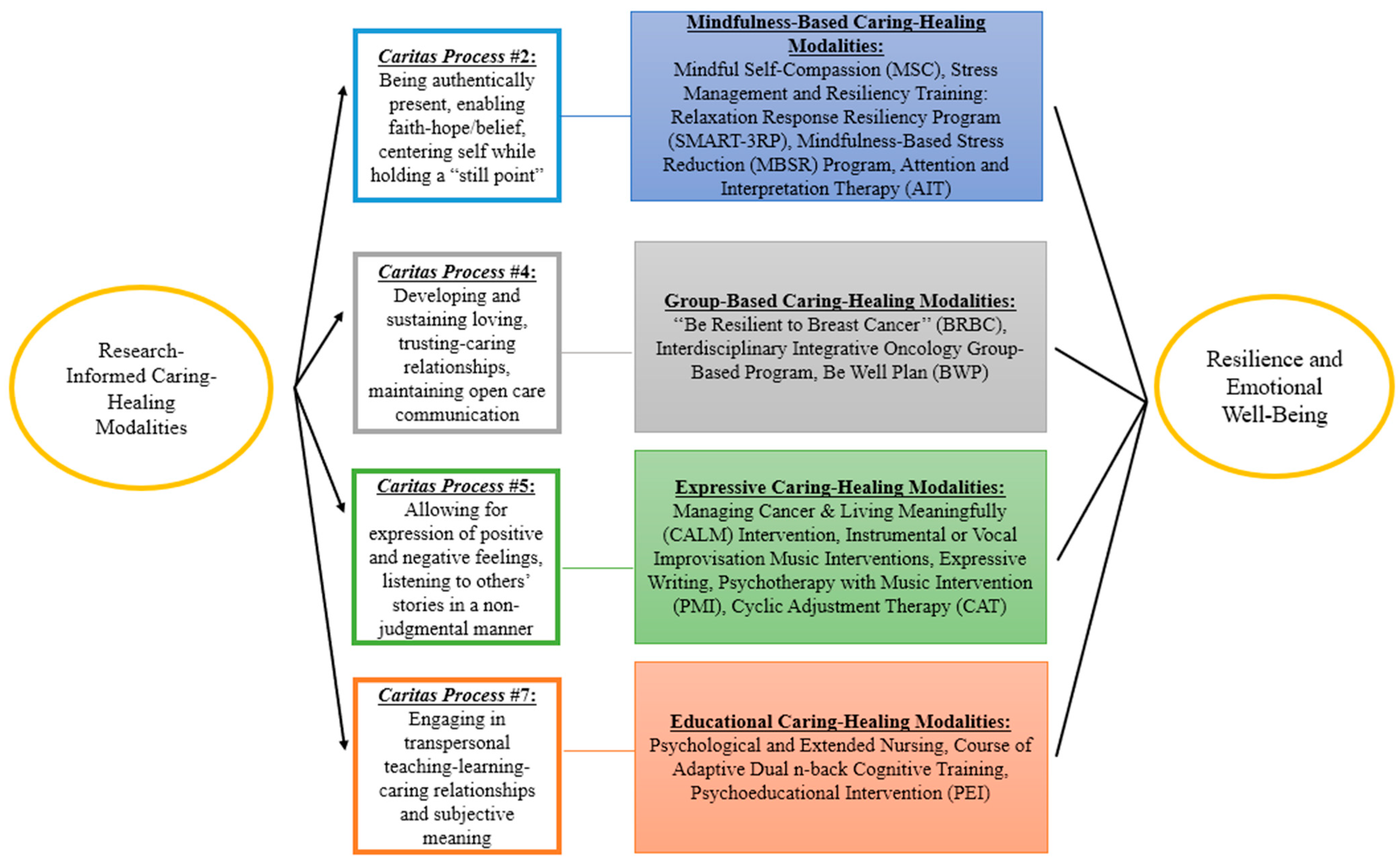

3.3.1. Mindfulness-Based Caring Healing Modalities (CP #2)

3.3.2. Group-Based Caring Healing Modalities (CP #4)

3.3.3. Expressive Caring Healing Modalities (CP #5)

3.3.4. Educational Caring Healing Modalities (CP #7)

3.3.5. Other Outcomes Assessed in the Sources of Evidence and Measurement Tools

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PwC | Persons with cancer |

| CHM | Caring-healing modality |

| CHMs | Caring–healing modalities |

| CPs | Caritas Processes |

| RCTs | Randomized Controlled Trials |

| (SMART-3RP) | Relaxation Response Resiliency Program |

| MSC | Mindful Self-Compassion |

| AIT | Attention and Interpretation Therapy |

| MBSR | Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction |

| BWP | Be Well Plan |

| BRBC | Be Resilient to Breast Cancer |

| CBT | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| ACT | Acceptance and Commitment Therapy |

| CAT | Cyclic Adjustment Therapy |

| CALM | Managing Cancer and Living Meaningfully |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| PEI | Psychoeducation Intervention |

References

- Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Cancer Stat Facts: Common Cancer Sites. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/common.html (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Corn, B.W.; Feldman, D.B. Cancer statistics, 2025: A hinge moment for optimism to morph into hope? CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Gonzalez, A.; Velasco-Durantez, V.; Martin-Abreu, C.; Cruz-Castellanos, P.; Hernandez, R.; Gil-Raga, M.; Garcia-Torralba, E.; Garcia-Garcia, T.; Jimenez-Fonseca, P.; Calderon, C. Fatigue, emotional distress, and illness uncertainty in patients with metastatic cancer: Results from the prospective NEOETIC_SEOM study. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 9722–9732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldiroli, C.L.; Sarandacchi, S.; Tomasuolo, M.; Diso, D.; Castiglioni, M.; Procaccia, R. Resilience as a mediator of quality of life in cancer patients in healthcare services. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.M.; Schofield, E.; Napolitano, S.; Avildsen, I.K.; Emanu, J.C.; Tutino, R.; Roth, A.J.; Nelson, C.J. African-centered coping, resilience, and psychological distress in Black prostate cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 2022, 31, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orom, H.; Nelson, C.J.; Underwood, W., 3rd; Homish, D.L.; Kapoor, D.A. Factors associated with emotional distress in newly diagnosed prostate cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 1416–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalata, W.; Gothelf, I.; Bernstine, T.; Michlin, R.; Tourkey, L.; Shalata, S.; Yakobson, A. Mental health challenges in cancer patients: A cross-sectional analysis of depression and anxiety. Cancers 2024, 16, 2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getie, A.; Ayalneh, M.; Bimerew, M. Global prevalence and determinant factors of pain, depression, and anxiety among cancer patients: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, W. Cancer-related psychosocial challenges. Gen. Psychiatry 2022, 35, e100871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groarke, A.; Curtis, R.; Skelton, J.; Groarke, J.M. Quality of life and adjustment in men with prostate cancer: Interplay of stress, threat and resilience. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.; Hardin, S.R.; Watson, J. A Unitary Caring Science resilience-building model: Unifying the human caring theory and research-informed psychology and neuroscience evidence. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2021, 8, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shan, H.; Wu, C.; Chen, H.; Shen, Y.; Shi, W.; Wang, L.; Li, Q. The mediating effect of self-efficacy on family functioning and psychological resilience in prostate cancer patients. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1392167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshields, T.L.; Asvat, Y.; Tippey, A.R.; Vanderlan, J.R. Distress, depression, anxiety, and resilience in patients with cancer and caregivers. Health Psychol. 2022, 41, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Li, M.; Wang, B.; Yuan, X.; Dong, B.; Yin, H.; Yang, Y. The relationship among resilience, anxiety and depression in patients with prostate cancer in China: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. Pract. 2023, 9, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.S.; Beatty, L.; Koczwara, B. Do cancer patients use the term resilience? A systematic review of qualitative studies. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukose, A. Developing a practice model for Watson’s Theory of Caring. Nurs. Sci. Q. 2011, 24, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürcan, M.; Turan, S.A. Examining the expectations of healing care environment of hospitalized children with cancer based on Watson’s Theory of Human Caring. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 3472–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, J. Metaphysics of Watson Unitary Caring Science: A Cosmology of Love; Springer Publishing Company, LLC.: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–298. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J. Nursing: The philosophy and science of caring. In Caring in Nursing Classics: An Essential Resource; Smith, M.C., Turkel, M.C., Wolf, Z.R., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company, LLC.: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 243–263. [Google Scholar]

- Christie, D.R.H.; Sharpley, C.F.; Bitsika, V. A systematic review of the association between psychological resilience and improved psychosocial outcomes in prostate cancer patients. Could resilience training have a potential role? World J. Mens. Health 2024, 43, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galway, K.; Black, A.; Cantwell, M.M.; Cardwell, C.R.; Mills, M.; Donnelly, M. Psychosocial interventions to improve quality of life and emotional wellbeing for recently diagnosed cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 11, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidani, S.; Braden, C.J. Nursing and Health Interventions. Design, Evaluation, and Implementation, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 50–51. [Google Scholar]

- Opalinski, A.S.; Martinez, L.A.; Butcher, H.; Bertulfo, T.; Stewart, D.; Gengo, R. A theory-guided literature review: A knowledge synthesis methodology. J. Nurs. Educ. 2025, 64, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; 2024; pp. 160–190. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acoba, E.F. Social support and mental health: The mediating role of perceived stress. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1330720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, S.M.; Khedr, M.A.; Tawfik, A.F.; Malek, M.G.N.; E-Ashry, A.M. The mediating and moderating role of social support on the relationship between psychological well-being and burdensomeness among elderly with chronic illness: Community nursing perspective. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software. Veritas Health Innovation: Melbourne, Australia, 2025. Available online: https://www.covidence.org (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and open synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Diao, Y.; Dong, Z.; Song, J.; Bao, C. The effect of attention and interpretation therapy on psychological resilience, cancer-related fatigue, and negative emotions of patients after colon cancer surgery. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2020, 9, 3261–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Huang, R.; Li, A.; Yu, S.; Yao, S.; Xu, J.; Tang, L.; Li, W.; Gan, C.; Cheng, H. Effects of the CALM intervention on resilience in Chinese patients with early breast cancer: A randomized trial. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 18005–18021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Yao, K.; Liu, X. Analysis on effect of psychological nursing combined with extended care for improving negative emotions and self-care ability in patients with colorectal cancer and enterostomy: A retrospective study. Medicine 2024, 103, e38165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.J.; Liang, M.Z.; Qiu, H.Z.; Liu, M.L.; Hu, G.Y.; Zhu, Y.F.; Zeng, Z.; Zhao, J.J.; Quan, X.M. Effect of a multidiscipline mentor-based program, Be Resilient to Breast Cancer (BRBC), on female breast cancer survivors in mainland China—A randomized, controlled, theoretically-derived intervention trial. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2016, 158, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.J.; Qiu, H.Z.; Liang, M.Z.; Liu, M.L.; Li, P.F.; Chen, P.; Sun, Z.; Yu, Y.L.; Wang, S.N.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Effect of a mentor-based, supportive-expressive program, Be Resilient to Breast Cancer, on survival in metastatic breast cancer: A randomised, controlled intervention trial. BJC 2017, 117, 1486–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Li, X. Effects of cyclic adjustment training delivered via a mobile device on psychological resilience, depression, and anxiety in Chinese post-surgical breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 178, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campo, R.A.; Bluth, K.; Santacroce, S.J.; Knapik, S.; Tan, J.; Gold, S.; Philips, K.; Gaylord, S.; Asher, G.N. A mindful self-compassion videoconference intervention for nationally recruited posttreatment young adult cancer survivors: Feasibility, acceptability, and psychosocial outcomes. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 1759–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein-Fox, L.; Bliss, C.C.; Rasmussen, A.W.; Hall, D.L.; El-Jawahri, A.; Perez, G.K. Do cancer curvivors and metavivors have distinct needs for stress management intervention? Retrospective analysis of a mind-body survivorship program. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondanaro, J.F.; Sara, G.A.; Thachil, R.; Pranjić, M.; Rossetti, A.; EunHye Sim, G.; Canga, B.; Harrison, I.B.; Loewy, J.V. The effects of clinical music therapy on resiliency in adults undergoing infusion: A randomized, controlled trial. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 61, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, M.M.; Locke, S.C.; Herring, K.W.; Somers, T.; LeBlanc, T.W. Expressive writing to address distress in hospitalized adults with acute myeloid leukemia: A pilot randomized clinical trial. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2024, 42, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.H.; Chen, S.W.; Huang, W.T.; Chang, S.C.; Hsu, M.C. Effects of a psychoeducational intervention in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. J. Nurs. Res. 2018, 26, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swainston, J.; Derakshan, N. Training cognitive control to reduce emotional vulnerability in breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2018, 27, 1780–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakki, S.E.; Penttinen, H.M.; Hilgert, O.M.; Volanen, S.M.; Saarto, T.; Raevuori, A. Mindfulness is associated with improved psychological well-being but no change in stress biomarkers in breast cancer survivors with depression: A single group clinical pilot study. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaş, B.B.; Märtens, B.; Cramer, H.; Voiss, P.; Longolius, J.; Weiser, A.; Ziert, Y.; Christiansen, H.; Steinmann, D. Effects of an interdisciplinary integrative oncology group-based program to strengthen resilience and improve quality of life in cancer patients: Results of a prospective longitudinal single-center study. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2022, 21, 15347354221081770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeppegno, P.; Krengli, M.; Ferrante, D.; Bagnati, M.; Burgio, V.; Farruggio, S.; Rolla, R.; Gramaglia, C.; Grossini, E. Psychotherapy with music intervention improves anxiety, depression and the redox status in breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Cancers 2021, 13, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckey, N.; van Agteren, J.; Chur-Hansen, A.; Ali, K.; Fassnacht, D.B.; Beatty, L.; Bareham, M.; Wardill, H.; Lasiello, M. Implementing a group-based online mental well-being program for women living with and beyond breast cancer—A mixed methods study. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 21, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynex, C.; Meehan, D.; Whittaker, K.; Buchanan, T.; Varlow, M. The need for improved integration of psychosocial and supportive care in cancer: A qualitative study of Australian patient perspectives. Support. Care Cancer 2025, 33, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiemen, A.; Czornik, M.; Weis, J. How effective is peer-to-peer support in cancer patients and survivors? A systematic review. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 9461–9485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizoğlu, H.; Gürkan, Z.; Bozkurt, Y.; Demir, C.; Akaltun, H. The effect of an improved environment according to Watson’s theory of human care on sleep, anxiety, and depression in patients undergoing open heart surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Healthcare 2025, 13, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y. A review on factors related to patient comfort experience in hospitals. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2023, 42, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Qan’ir, Y.; Guan, T.; Guo, P.; Xu, S.; Jung, A.; Idiagbonya, E.; Song, F.; Kent, E.E. The challenges of enrollment and retention: A systematic review of psychosocial behavioral interventions for patients with cancer and their family caregivers. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, e279–e304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, F.; Wang, G.; Liu, L.; Hu, X. Recent evidence and progress for developing precision nursing in symptomatology: A scoping review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2023, 70, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, J.W. Using the profile of caring: Measuring nurses’ caring for self and caring by their unit manager. Creat. Nurs. 2022, 28, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kociolek, J.; Gengo, R.; Chiang-Hanisko, L. Caring-Healing Modalities for Emotional Distress and Resilience in Persons with Cancer: A Scoping Review. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090334

Kociolek J, Gengo R, Chiang-Hanisko L. Caring-Healing Modalities for Emotional Distress and Resilience in Persons with Cancer: A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(9):334. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090334

Chicago/Turabian StyleKociolek, Judyta, Rita Gengo, and Lenny Chiang-Hanisko. 2025. "Caring-Healing Modalities for Emotional Distress and Resilience in Persons with Cancer: A Scoping Review" Nursing Reports 15, no. 9: 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090334

APA StyleKociolek, J., Gengo, R., & Chiang-Hanisko, L. (2025). Caring-Healing Modalities for Emotional Distress and Resilience in Persons with Cancer: A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports, 15(9), 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090334