Factors Associated with Post-Intensive Care Syndrome in Patients Attending a Hospital in Northern Colombia: A Quantitative and Correlational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Scope and Period

2.3. Population Sample and Sampling

2.4. Variables and Instruments

2.4.1. Characterization Sheet

2.4.2. Healthy Aging Brain Care Monitor (HABC-M)

2.5. Data Collection Procedure

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

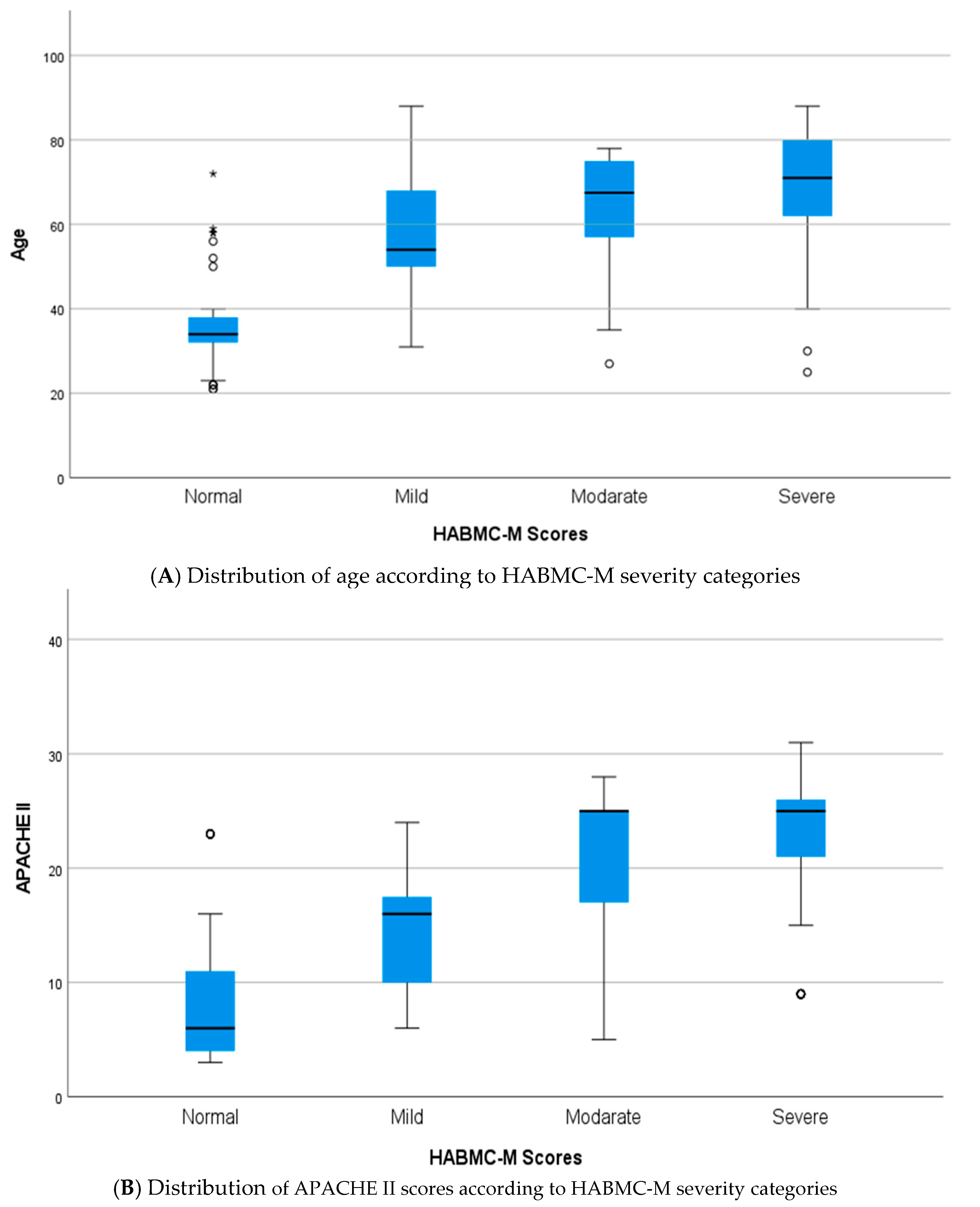

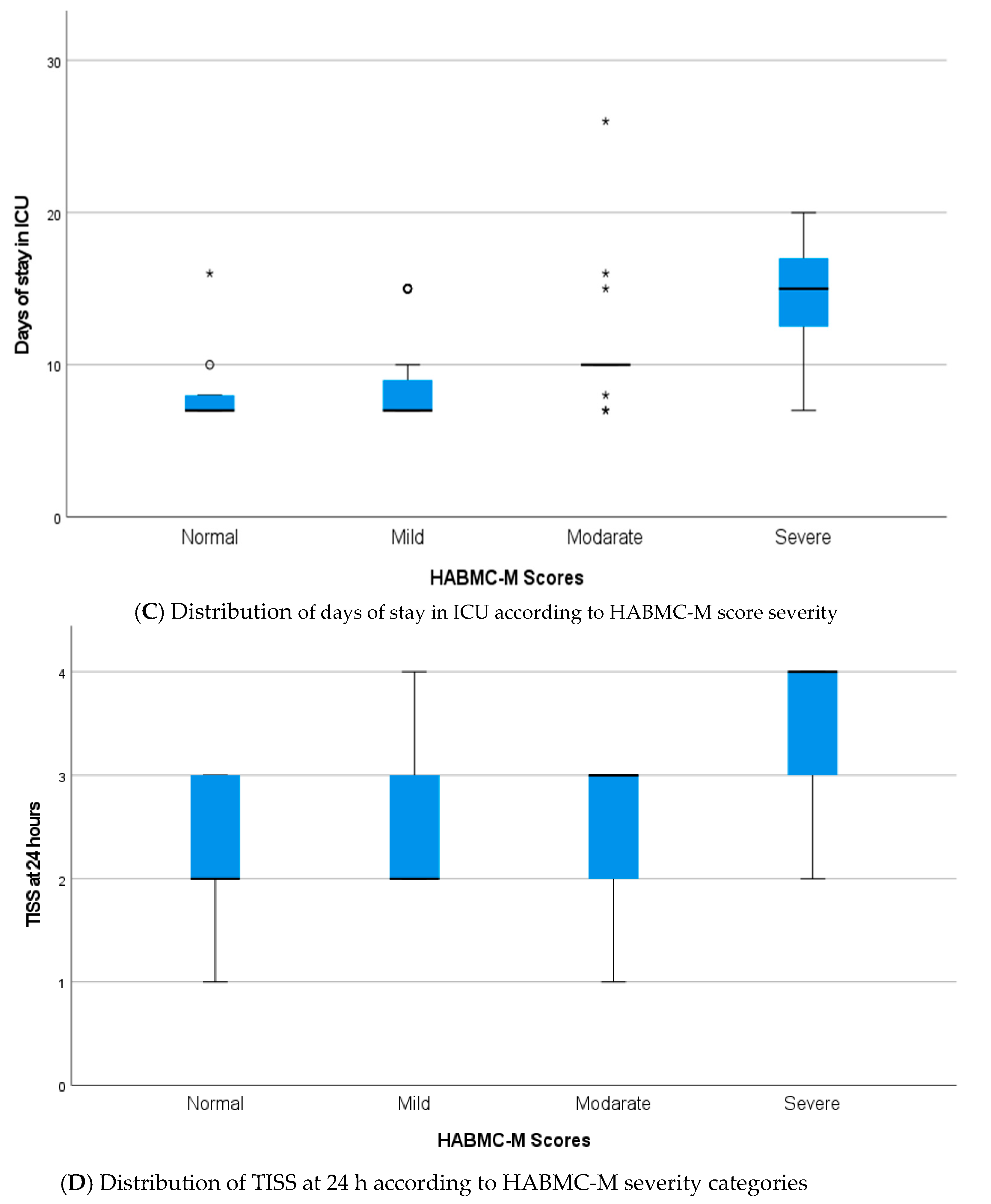

3.2. Relationship Between Variables and HABC-M Scale

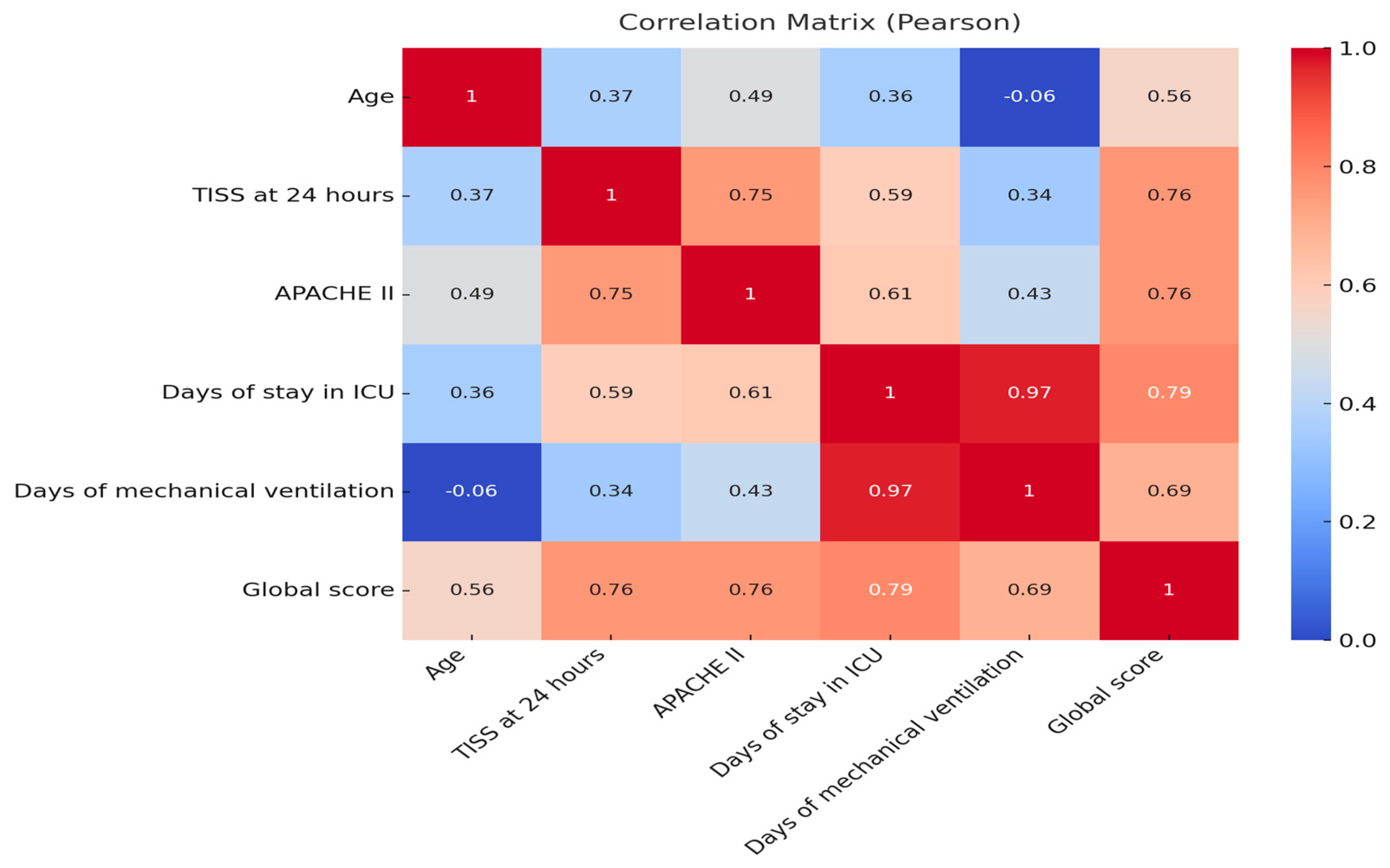

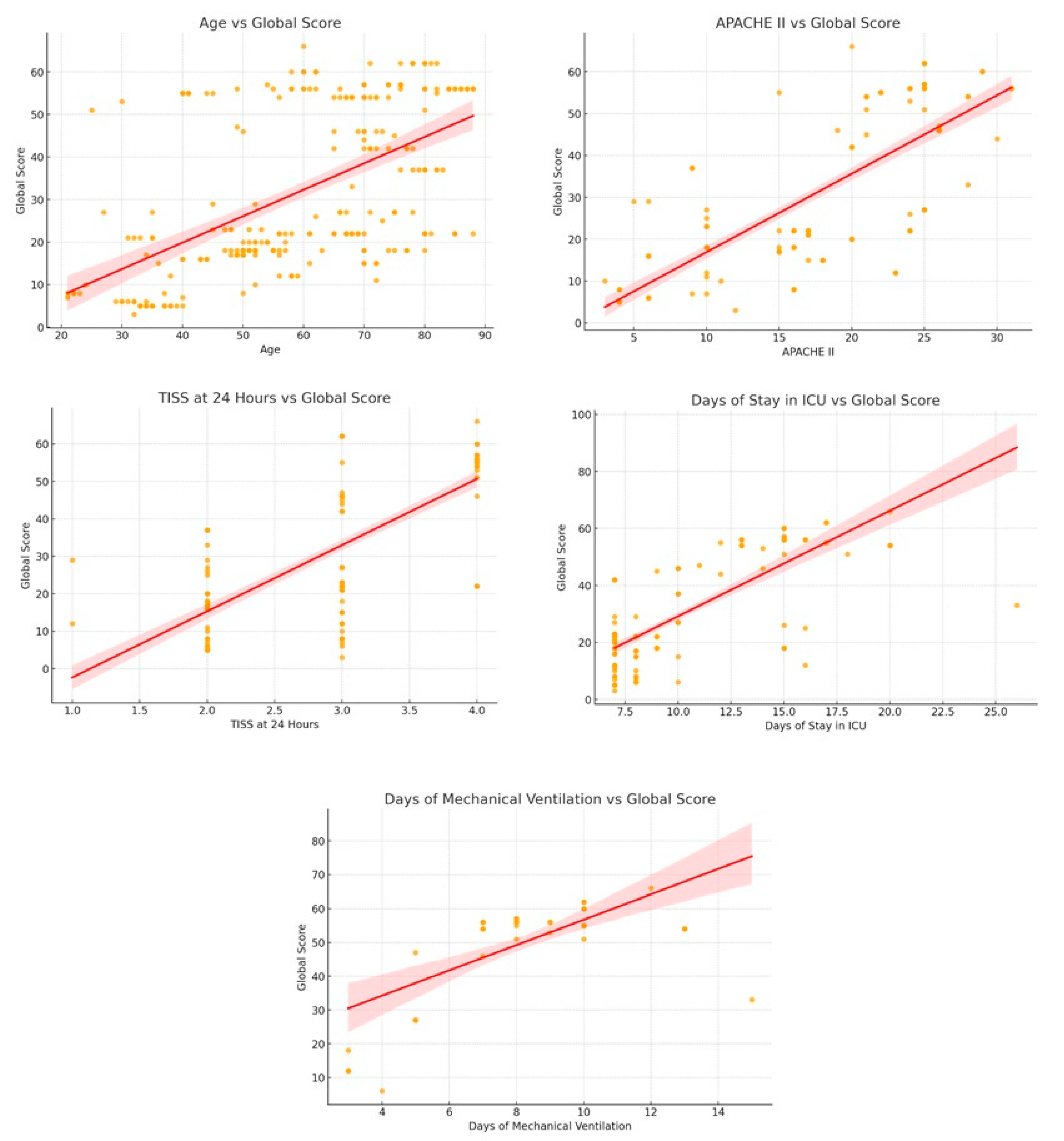

3.3. Correlation Analysis

3.4. Logistic Regression Model to Predict High HABC-M Scale Scores

4. Discussion

Limitations and Implications for Nursing

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Abbreviations

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| SCCM | Society Critical Care Medicine |

| PICS | Post Intensive Care Syndrome |

| APACHE II | Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II |

| HABC-M | Healthy Aging Brain Care Monitor |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PICS-F | Post Intensive Care Family Syndrome |

| DM2 | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| DM1 | Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus |

| AHT | Arterial Hypertension |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

References

- Needham, D.M.; Davidson, J.; Cohen, H.; Hopkins, R.O.; Weinert, C.; Wunsch, H.; Zawistowski, C.; Bemis-Dougherty, A.; Berney, S.C.; Bienvenu, O.J.; et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: Report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, K.J.; Leoutsakos, J.M.S.; Yan, H.; Lin, S.; Zabinski, J.S.; Dinglas, V.D.; Hosey, M.M.; Parker, A.M.; Hopkins, R.O.; Needham, D.M. Fatigue Symptoms During the First Year Following ARDS. Chest 2020, 158, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geense, W.W.; Zegers, M.; Peters, M.A.A.; Ewalds, E.; Simons, K.S.; Vermeulen, H.; Van Der Hoeven, J.G.; Van Den Boogaard, M. New physical, mental, and cognitive problems 1 year after ICU admission: A prospective multicenter study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 203, 1512–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiser, S.L.; Fatima, A.; Ali, M.; Needham, D.M. Post-intensive care syndrome (PICS): Recent updates. J. Intensive Care 2023, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Allen, D.; Perkins, A.; Monahan, P.; Khan, S.; Lasiter, S.; Boustani, M.; Khan, B. Validation of a New Clinical Tool for Post-Intensive Care Syndrome. Am. J. Crit. Care 2019, 28, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, G.; Yadav, S.; Kumar, R. Post-intensive care syndrome: An overview. J. Transl. Intern. Med. 2017, 5, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, A.; Wilson, C.; Zelenkov, D.; Adams, K.; Poyant, J.O.; Han, X.; Faugno, A.; Montalvo, C. The Psychiatric Domain of Post-Intensive Care Syndrome: A Review for the Intensivist. J. Intensive Care Med. 2024. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangayach, N.S.; Kreitzer, N.; Foreman, B.; Tosto-Mancuso, J. Post-Intensive Care Syndrome in Neurocritical Care Patients. Semin. Neurol. 2024, 44, 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, L.; Subair, M.N.; Munjal, J.; Singh, B.; Bansal, V.; Gupta, V.; Jain, R. Beyond survival: Understanding post-intensive care syndrome. Acute Crit. Care 2024, 39, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornemann-Cimenti, H.; Lang, J.; Hammer, S.; Lang-Illievich, K.; Labenbacher, S.; Neuwersch-Sommeregger, S.; Klivinyi, C. Consensus-Based Recommendations for Assessing Post-Intensive Care Syndrome: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejero-Aranguren, J.; Martin, R.G.M.; Poyatos-Aguilera, M.E.; Martin, M.; Poyatos-Aguilera, M.E.; Morales-Galindo, I.; Cobos-Vargas, A.; Colmenero, M. Incidência e fatores de risco associados à síndrome pós-cuidados intensivos em uma coorte de pacientes em estado crítico. Rev. Bras. De. Ter. Intensiv. 2022, 34, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Lee, M.H. Incidence rate and risk factors for post-intensive care syndrome subtypes among critical care survivors three months after discharge: A prospective cohort study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2024, 81, 103605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzgarrou, R.; Farigon, N.; Morlat, L.; Bouaziz, S.; Philipponet, C.; Laurichesse, G.; Calvet, L.; Cassagnes, L.; Costes, F.; Souweine, B.; et al. Incidence of post-intensive care syndrome among patients admitted to post-ICU multidisciplinary consultations: The retrospective observational PICS-MIR study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Navarro, V.; Poblete-Figueroa, C.; Freire-Figueroa, F.; Villarroel-Sgorbini, C.; Lagos-Vásquez, D.; Carrasco-Barrera, A.; Núñez-Hernández, N.; Oportus-Díaz, S.; Muñoz-Sotelo, C.; Avello-Molina, H.; et al. Rehabilitación domiciliara de pacientes con síndrome post UCI por COVID-19. Hosp. A Domic. 2023, 7, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henao-Castaño, Á.M.; Vanessa, A.; Buitrago, V.; Marín Ramírez, S.; Cogollo Hernández, C.A.; De Autor, N. Características del síndrome post cuidado intensivo: Revisión de alcance. Investig. En. Enfermería Imagen Y Desarro. 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbenson, G.A.; Johnson, A.; Wilson, M.E. Post-intensive care syndrome: Impact, prevention, and management. Breathe 2019, 15, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama, J.; Inoue, S.; Liu, K.; Yamakawa, K.; Nishida, T.; Ohshimo, S.; Hashimoto, S.; Kanda, N.; Maruyama, S.; Ogata, Y.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factor Analysis of Post-Intensive Care Syndrome in Patients with COVID-19 Requiring Mechanical Ventilation: A Multicenter Prospective Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.A.; Sandi, M.; Bixby, J.; Perry, G.; Offner, P.J.; Burnham, E.L.; Jolley, S.E. An Exploratory Analysis of Sociodemographic Factors Associated with Physical Functional Impairment in ICU Survivors. Crit. Care Explor. 2024, 6, e1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaws, D.; Fraser, J.F.; Laupland, K.; Lavana, J.; Patterson, S.; Tabah, A.; Tronstad, O.; Ramanan, M. Time in ICU and post-intensive care syndrome: How long is long enough? Crit. Care 2021, 28, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narváez-Martínez, M.A.; Henao-Castaño, Á.M. Severity classification and influencing variables of the Postintensive Care Syndrome. Enfermería Intensiv. (Engl. Ed.) 2024, 35, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPeake, J.; Mikkelsen, M.E.; Quasim, T.; Hibbert, E.; Cannon, P.; Shaw, M.; Ankori, J.; Iwashyna, T.J.; Haines, K.J. Return to employment after critical illness and its association with psychosocial outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2019, 16, 1304–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Fuentes, A.L.; Chen, H.; Malhotra, A.; Gallo, L.C.; Song, Y.; Moore, R.C.; Kamdar, B.B. The Financial Impact of Post Intensive Care Syndrome. Crit. Care Clin. 2024, 41, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narváez Martínez, M.A.; Henao Castaño, Á.M. Validation into Spanish of a Scale to Detect the Post-intensive Care Syndrome. Investig. Y Educ. En. Enfermería 2023, 41, e09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monahan, P.; Boustani, M.; Alder, C.; Galvin, J.; Perkins, A.J.; Healey, P.; Chehresa, A.; Shepard, P.; Bubp, C.; Frame, A.; et al. Practical clinical tool to monitor dementia symptoms: The HABC-Monitor. Clin. Interve Aging 2012, 7, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Salud de Colombia. Resolución 8430 de 1993—Colombia. (1993, October 4). Ministerio de Salud de Colombia. Available online: https://www.redjurista.com/Documents/resolucion_8430_de_1993.aspx#/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Haddad, D.N.; Mart, M.F.; Wang, L.; Lindsell, C.J.; Raman, R.; Nordness, M.F.; Sharp, K.W.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Girard, T.D.; Ely, E.W.; et al. Socioeconomic Factors and Intensive Care Unit-Related Cognitive Impairment. Ann. Surg. 2020, 272, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schembari, G.; Santonocito, C.; Messina, S.; Caruso, A.; Cardia, L.; Rubulotta, F.; Noto, A.; Bignami, E.G.; Sanfilippo, F. Post-Intensive Care Syndrome as a Burden for Patients and Their Caregivers: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pun, B.T.; Balas, M.C.; Barnes-Daly, M.A.; Thompson, J.L.; Aldrich, J.M.; Barr, J.; Byrum, D.; Carson, S.S.; Devlin, J.W.; Engel, H.J.; et al. Caring for Critically Ill Patients with the ABCDEF Bundle: Results of the ICU Liberation Collaborative in Over 15,000 Adults. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 47, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, M.O.; Egerod, I.; Thomsen, T.; Wetterslev, J.; Lange, T.; Ebdrup, B.H.; Perner, A. Risk factors for long-term cognitive impairment in ICU survivors: A multicenter, prospective cohort study. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2021, 65, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirasaki, K.; Hifumi, T.; Nakanishi, N.; Nosaka, N.; Miyamoto, K.; Komachi, M.H.; Haruna, J.; Inoue, S.; Otani, N. Postintensive care syndrome family: A comprehensive review. Acute Med. Surg. 2024, 11, e939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekong, M.; Monga, T.S.; Daher, J.C.; Sashank, M.; Soltani, S.R.; Nwangene, N.L.; Mohammed, C.; Halfeld, F.F.; AlShelh, L.; Fukuya, F.A.; et al. From the Intensive Care Unit to Recovery: Managing Post-intensive Care Syndrome in Critically Ill Patients. Cureus 2024, 16, e61443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatakeyama, J.; Nakamura, K.; Inoue, S.; Liu, K.; Yamakawa, K.; Nishida, T.; Ohshimo, S.; Hashimoto, S.; Kanda, N.; Aso, S.; et al. Two-year trajectory of functional recovery and quality of life in post-intensive care syndrome: A multicenter prospective observational study on mechanically ventilated patients with coronavirus disease-19. J. Intensive Care 2025, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanwani-Nanwani, K.; López-Pérez, L.; Giménez-Esparza, C.; Ruiz-Barranco, I.; Carrillo, E.; Arellano, M.S.; Díaz-Díaz, D.; Hurtado, B.; García-Muñoz, A.; Relucio, M.Á.; et al. Prevalence of post-intensive care syndrome in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iribarren-Diarasarri, S.; Bermúdez-Ampudia, C.; Barreira-Méndez, R.; Vallejo-Delacueva, A.; Bediaga-Díazdecerio, I.; Martínez-Alútiz, S.; Ruilope-Alvaro, L.; Vinuesa-Lozano, C.; Aretxabala-Cortajarena, N.; San Sebastián-Hurtado, A.; et al. Post-intensive care syndrome at one month after hospital discharge in critically ill patients surviving COVID-19. Med. Intensiv. 2023, 47, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, M.; Miyamoto, K.; Shima, N.; Nakashima, T.; Kunitatsu, K.; Yonemitsu, T.; Kawabata, A.; Kishi, Y.; Kato, S. Activities of daily living and psychiatric symptoms after intensive care unit discharge among critically ill patients with or without tracheostomy: A single center longitudinal study. Acute Med. Surg. 2022, 9, e753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Kang, J.; Jeong, Y.J. Risk factors for post–intensive care syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust. Crit. Care 2020, 33, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, S.; Nakanishi, N.; Amaya, F.; Fujinami, Y.; Hatakeyama, J.; Hifumi, T.; Iida, Y.; Kawakami, D.; Kawai, Y.; Kondo, Y.; et al. Post-intensive care syndrome: Recent advances and future directions. Acute Med. Surg. 2024, 11, e929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, E.; Aguilera, C.; Márquez, D.; Ziegler, G.; Plumet, J.; Tschopp, L.; Cominotti, C.; Sturzenegger, V.; Cimino, C.; Escobar, H.; et al. Post intensive care syndrome in survivors of COVID-19 who required mechanical ventilation during the third wave of the pandemic: A prospective study. Heart Lung 2023, 62, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, D.; Fujitani, S.; Morimoto, T.; Dote, H.; Takita, M.; Takaba, A.; Hino, M.; Nakamura, M.; Irie, H.; Adachi, T.; et al. Prevalence of post-intensive care syndrome among Japanese intensive care unit patients: A prospective, multicenter, observational J-PICS study. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voiriot, G.; Oualha, M.; Pierre, A.; Salmon-Gandonnière, C.; Gaudet, A.; Jouan, Y.; Kallel, H.; Radermacher, P.; Vodovar, D.; Sarton, B.; et al. Chronic critical illness and post-intensive care syndrome: From pathophysiology to clinical challenges. Ann. Intensive Care 2022, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramnarain, D.; Pouwels, S.; Fernández-Gonzalo, S.; Navarra-Ventura, G.; Balanzá-Martínez, V. Delirium-related psychiatric and neurocognitive impairment and the association with post-intensive care syndrome—A narrative review. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2023, 147, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Category | n | % | Mean/SD * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 59.2 ± 17.3 | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 187 | 67.5 | ||

| Female | 90 | 32.5 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 135 | 48.7 | ||

| Married | 127 | 45.8 | ||

| Other/widowed † | 15 | 5.4 | ||

| Educational level | ||||

| Primary | 71 | 25.3 | ||

| Baccalaureate | 82 | 29.6 | ||

| Higher education | 98 | 35.3 | ||

| Technical studies | 26 | 9.4 | ||

| Employment status | ||||

| Worker | 143 | 51.6 | ||

| Does not work | 73 | 26.3 | ||

| Housewife | 56 | 20.2 | ||

| Student | 5 | 1.8 | ||

| Religion | ||||

| Catholic | 187 | 67.5 | ||

| Evangelical | 80 | 28.8 | ||

| Not professed | 10 | 3.6 | ||

| Provenance | ||||

| Urban | 206 | 74.3 | ||

| Rural | 71 | 25.6 | ||

| Clinical conditions of admission to the ICU due to altered systems | ||||

| Cardiovascular | 81 | 29.2 | ||

| Cardiovascular + neurological | 59 | 21.2 | ||

| Neurological | 53 | 19.2 | ||

| Respiratory | 42 | 15.1 | ||

| Other/mixed | 42 | 15.1 | ||

| Personal Antecedents | ||||

| AHT | 82 | 29.6 | ||

| AHT + DM2 | 64 | 23.1 | ||

| COPD | 44 | 15.8 | ||

| DM2 | 34 | 12.2 | ||

| Other/none | 53 | 19.1 | ||

| APACHE II | 17.3 ± 7.8 | |||

| Days of stay in ICU | 10.7 ± 4 | |||

| Sedatives | ||||

| Fentanyl | 107 | 38.6 | ||

| Midazolam | 64 | 23.1 | ||

| Dexmedetomide | 44 | 15.8 | ||

| Mechanical ventilation | ||||

| Yes | 107 | 38.6 | ||

| No | 170 | 61.3 | ||

| Mechanical ventilation days | 8.3 ± 2.5 | |||

| Tracheostomy | ||||

| Yes | 21 | 7.6 | ||

| No | 256 | 92.4 |

| Total Score HABC-M Scale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | Normal | Slight | Moderate | Severe | p-Value |

| Religion | Catholic | 33 | 63 | 4 | 87 | 0.001 |

| Evangelical | 8 | 31 | 12 | 29 | ||

| Not professed | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Educational level | Primary | 1 | 30 | 2 | 38 | 0.001 |

| Baccalaureate | 14 | 30 | 11 | 27 | ||

| Technical studies | 1 | 21 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Higher education | 30 | 18 | 1 | 49 | ||

| Marital status | Single | 31 | 53 | 3 | 48 | 0.001 |

| Married | 11 | 35 | 13 | 68 | ||

| Free union | 4 | 11 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Employment status | Housewife | 1 | 17 | 0 | 38 | 0.001 |

| Worker | 40 | 75 | 4 | 24 | ||

| Does not work | 0 | 7 | 12 | 54 | ||

| Student | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Clinical conditions of admission to the ICU due to altered systems | Neurological | 2 | 20 | 0 | 31 | 0.001 |

| Cardiovascular | 5 | 42 | 4 | 30 | ||

| Respiratory | 5 | 9 | 1 | 27 | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 11 | 12 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Cardiovascular + neurological | 16 | 6 | 11 | 26 | ||

| Endocrine | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Kidney | 0 | 10 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Personal antecedents | AHT + DM2 | 3 | 28 | 12 | 21 | 0.001 |

| DM2 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 23 | ||

| AHT | 13 | 32 | 2 | 35 | ||

| DM1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| CKD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | ||

| AHT + DM2 + CKD | 1 | 19 | 0 | 1 | ||

| COPD | 5 | 10 | 0 | 29 | ||

| Other | 11 | 6 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Mechanical ventilation | Yes | 6 | 1 | 11 | 89 | 0.001 |

| No | 40 | 98 | 5 | 27 | ||

| Tracheostomy | Yes | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0.001 |

| No | 46 | 99 | 15 | 96 | ||

| Cardiovascular treatment | Yes | 4 | 87 | 14 | 115 | 0.001 |

| No | 42 | 12 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Nitroglycerin | No | 41 | 55 | 11 | 87 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 2 | 44 | 3 | 29 | ||

| Nitroprusside | No | 46 | 84 | 16 | 106 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 0 | 15 | 0 | 10 | ||

| Norepinephrine | No | 43 | 87 | 6 | 40 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 0 | 12 | 10 | 75 | ||

| Dopamine | No | 46 | 98 | 16 | 49 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 0 | 1 | 0 | 66 | ||

| Labetalol | No | 46 | 97 | 15 | 116 | 0.087 |

| Yes | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Sedatives | Yes | 7 | 18 | 12 | 99 | |

| No | 39 | 81 | 4 | 17 | ||

| Dexmedetomide | No | 46 | 88 | 4 | 96 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 0 | 11 | 12 | 20 | ||

| Fentanyl | No | 40 | 97 | 5 | 27 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 6 | 2 | 11 | 89 | ||

| Midazolam | No | 45 | 93 | 16 | 58 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 1 | 6 | 0 | 58 | ||

| Diazepam | No | 45 | 93 | 16 | 115 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Antibiotic treatment | Yes | 10 | 39 | 2 | 76 | 0.001 |

| No | 36 | 60 | 14 | 40 | ||

| Piperacillin_tazobactam | No | 46 | 71 | 15 | 68 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 0 | 28 | 1 | 48 | ||

| Cefepime | No | 45 | 88 | 15 | 115 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 1 | 11 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Ampcillin_sulbactam | No | 46 | 89 | 16 | 89 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 0 | 10 | 0 | 27 | ||

| Clarithromycin | No | 46 | 99 | 16 | 96 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | ||

| Others | No | 38 | 91 | 16 | 78 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 8 | 8 | 0 | 38 | ||

| Pearson Correlation | CI 95% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | p-Value | ||

| Global score—Age | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.64 | 0.00 |

| Global score—TISS at 24 h | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.00 |

| Global score—APACHE II | 0.76 | 0.71 | 0.81 | 0.00 |

| Global score—Days of stay in ICU | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.00 |

| Global score—Mechanical ventilation days | 0.69 | 0.57 | 0.78 | 0.00 |

| CI 95% | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | OR | Lower | Upper | p-Value |

| Received cardiovascular treatment (Yes) | 4.385 | 80.21 | 1.46 | 7.31 | 0.00 |

| Received antibiotic treatment (Yes) | 4.529 | 92.62 | 2.21 | 6.85 | 0.00 |

| Fentanyl (Yes) | 12.840 | 376,962.13 | 0.21 | 25.47 | 0.05 |

| Midazolam (Yes) | −4.960 | 0.01 | −9.02 | −0.90 | 0.02 |

| Religion (Evangelical) | −11.874 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Educational level [T. Primary] | −3.223 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.02 |

| Provenance [T. Urban] | −3.199 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.02 |

| Employment status [T. Does not work] | 4.802 | 121.71 | 3.34 | 4435.53 | 0.01 |

| Marital Status [T. Single] | −5.314 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| Age | 0.291 | 1.34 | 1.25 | 1.44 | 0.00 |

| TISS at 24 h | 8.317 | 4093.25 | 565.12 | 29,648.21 | 0.00 |

| APACHE II | 0.511 | 1.67 | 1.35 | 2.06 | 0.00 |

| Days of stay in ICU | 2.321 | 10.19 | 7.75 | 13.40 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herrera Herrera, J.L.; Llorente Pérez, Y.J.; Oyola López, E.; Jiménez Hernández, G.E. Factors Associated with Post-Intensive Care Syndrome in Patients Attending a Hospital in Northern Colombia: A Quantitative and Correlational Study. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090311

Herrera Herrera JL, Llorente Pérez YJ, Oyola López E, Jiménez Hernández GE. Factors Associated with Post-Intensive Care Syndrome in Patients Attending a Hospital in Northern Colombia: A Quantitative and Correlational Study. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(9):311. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090311

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerrera Herrera, Jorge Luis, Yolima Judith Llorente Pérez, Edinson Oyola López, and Gustavo Edgardo Jiménez Hernández. 2025. "Factors Associated with Post-Intensive Care Syndrome in Patients Attending a Hospital in Northern Colombia: A Quantitative and Correlational Study" Nursing Reports 15, no. 9: 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090311

APA StyleHerrera Herrera, J. L., Llorente Pérez, Y. J., Oyola López, E., & Jiménez Hernández, G. E. (2025). Factors Associated with Post-Intensive Care Syndrome in Patients Attending a Hospital in Northern Colombia: A Quantitative and Correlational Study. Nursing Reports, 15(9), 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15090311