Preventive Health Behavior and Readiness for Self-Management in a Multilingual Adult Population: A Representative Study from Northern Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How does preventive health behavior, as measured by the GHP-16 scale, vary across sociodemographic subgroups (e.g., age, sex, education level, and linguistic group) in South Tyrol?

- Is mistrust in health information from professional sources associated with lower GHP-16 scores, independent of sociodemographic and psychosocial factors?

- To what extent are health literacy and patient activation associated with GHP-16 scores after adjusting for sociodemographic variables?

2. Methods

2.1. Study Context and Sampling Framework

2.2. Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics

2.3. Assessment of Health Behavior (GHP-16)

- “I go regularly to the doctor for a check-up”.

- “I collect information about things that concern my health”.

- “I let myself be vaccinated”.

2.4. Health Literacy and Patient Activation

- “How easy is it for you to understand what your doctor says to you?”.

- “How easy is it to judge whether the health information in the media is reliable?”.

- “I am confident that I can take actions that will help prevent or minimize some symptoms or problems associated with my health condition”.

- “I am confident that I can tell a doctor concerns I have even when he or she does not ask”.

2.5. Mistrust in Health Information

2.6. Statistical Analyses

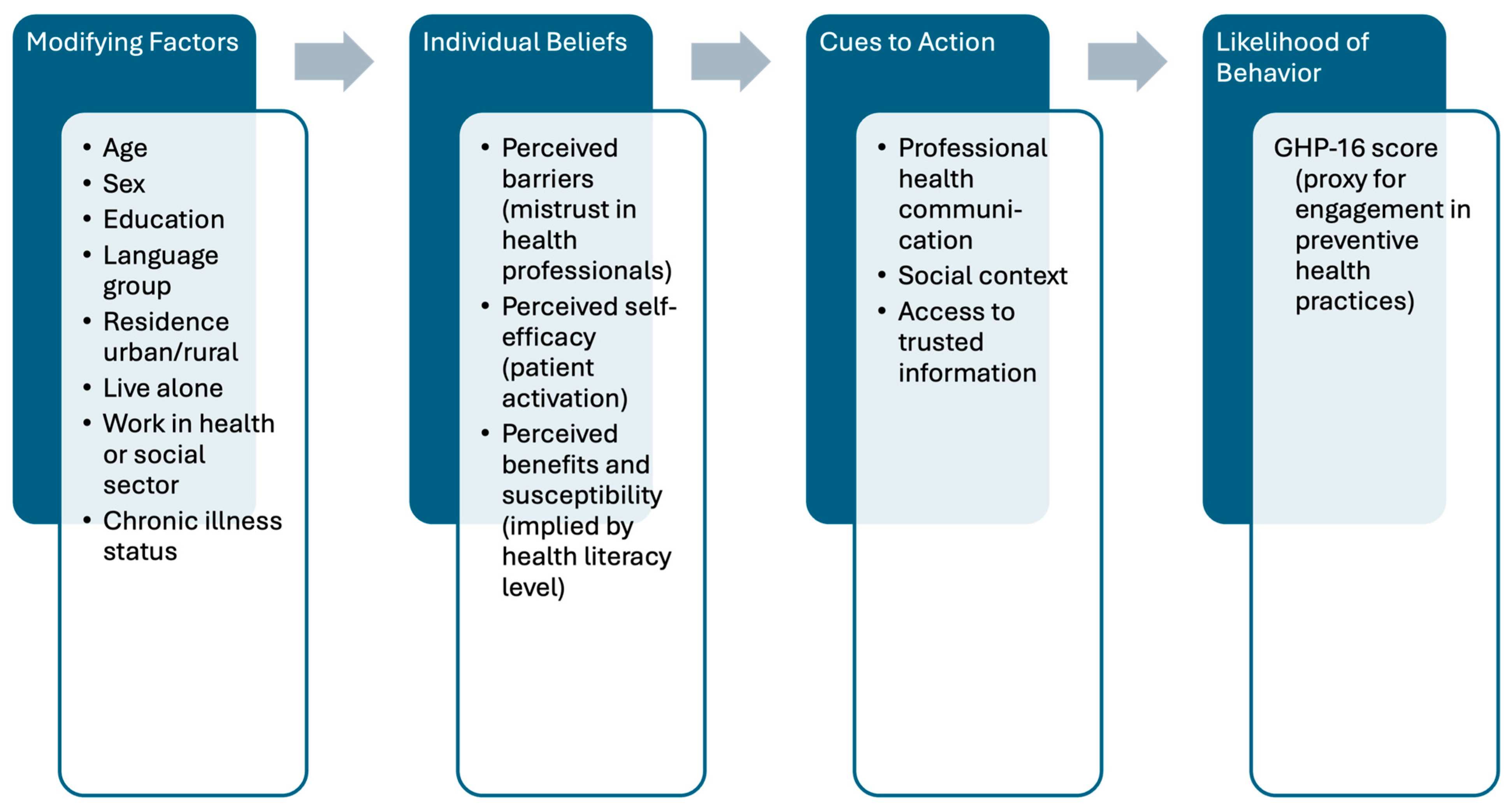

Regression Modeling and Covariate Selection

3. Results

3.1. Variation in Health-Promoting Behavior Across Sociodemographic and Psychosocial Characteristics

3.2. Associations of Mistrust, Health Literacy, Patient Activation, and Sociodemographic Predictors with Preventive Health Behavior

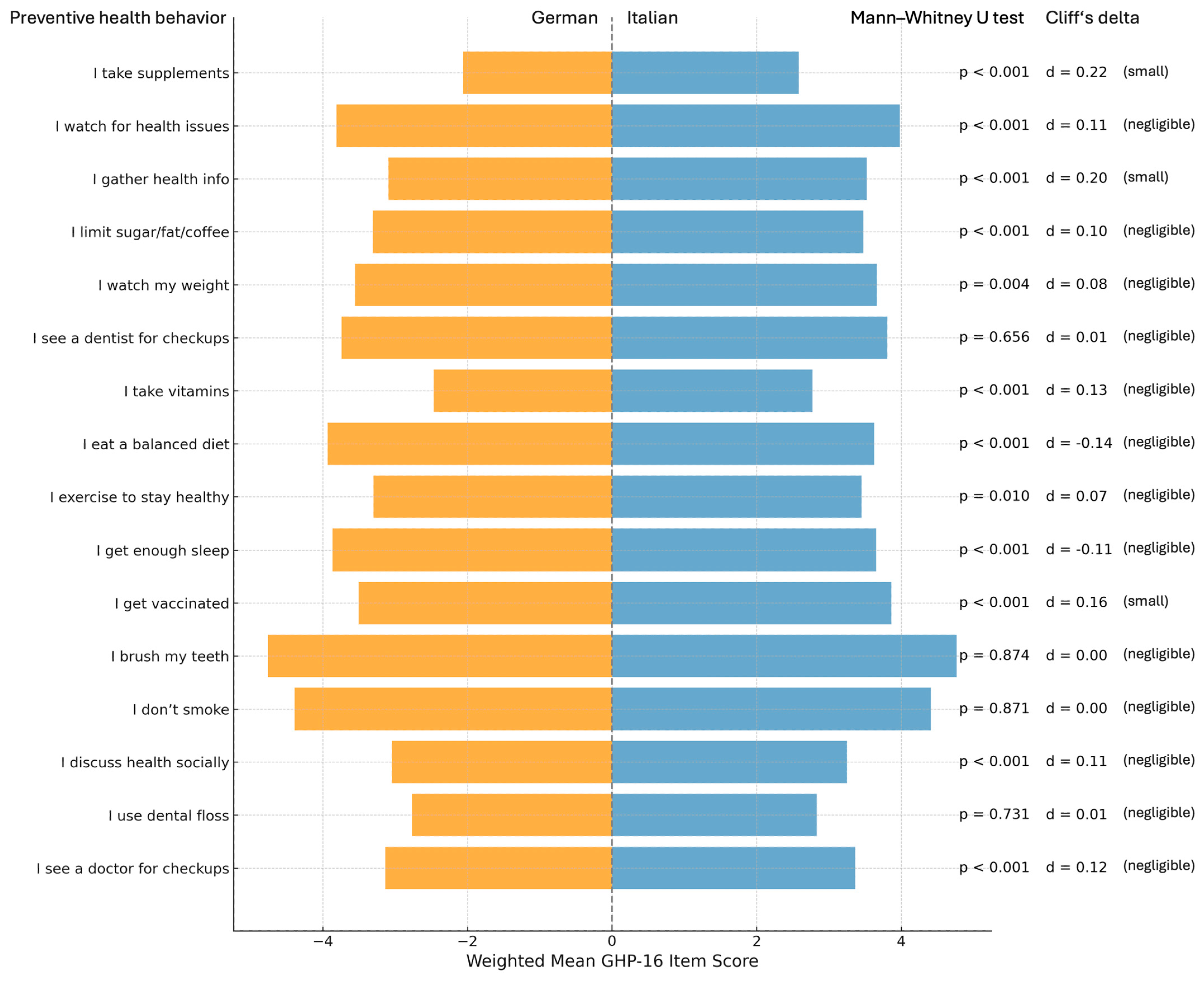

3.3. Health-Promoting Behavior by Language Group: German vs. Italian

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation in Light of the Existing Literature

4.2. Language Group Differences and Cultural Implications

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Public Health and Policy Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASTAT | Provincial Institute of Statistics of South Tyrol |

| B-PSQI | Brief Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| GHP-16 | Good Health Practice 16 Items |

| HBC | Health Behavior Checklist |

| HBM | Health Belief Model |

| HLS-EU-Q16 | Health Literacy Survey EU Questionnaire 16 Items |

| PAM-10 | Patient Activation Measure 10 Items |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| VIFs | Variance Inflation Factors |

| WLR | Weighted Linear Regression |

References

- Hampson, S.E.; Edmonds, G.W.; Goldberg, L.R. The Health Behavior Checklist: Factor Structure in Community Samples and Validity of a Revised Good Health Practices Scale. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, R.R.; Conway, T.L.; Hervig, L.K. Demonstration of Replicable Dimensions of Health Behaviors. Prev. Med. 1990, 19, 377–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsell, D.J.; Everhart, R.S.; Miadich, S.A.; Trujillo, M.A. Examining Health Behaviors, Health Literacy, and Self-Efficacy in College Students with Chronic Conditions. Am. J. Health Educ. 2018, 49, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, G.R.; Lutgendorf, S.K. Perceived Health Competence and Personality Factors Differentially Predict Health Behaviors in Older Adults. J. Aging Health 1999, 11, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaroslava, D.; Helena, K.; Iva, B. Health-Related Behavior over the Course of Life in the Czech Republic. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 217, 1167–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, R. What Part of Italy Has the Highest Life Expectancy? In Geographic FAQ Hub: Answers to Your Global Questions; 2025; Available online: https://www.ncesc.com/geographic-faq/what-part-of-italy-has-the-highest-life-expectancy/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Barbieri, V.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Lombardo, S.; Piccoliori, G.; Gärtner, T.; Engl, A. Vaccine Hesitancy and Public Mistrust during Pandemic Decline: Findings from 2021 and 2023 Cross-Sectional Surveys in Northern Italy. Vaccines 2024, 12, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, V.; Lombardo, S.; Gärtner, T.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A.; Wiedermann, C.J. Trust in Conventional Healthcare and the Utilization of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in South Tyrol, Italy: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Annali di Igiene Medicina Preventiva e di Comunità 2024, 36, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedermann, C.J.; Barbieri, V.; Plagg, B.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A. Vaccine Hesitancy in South Tyrol: A Narrative Review of Insights and Strategies for Public Health Improvement. Annali di Igiene Medicina Preventiva e di Comunità 2024, 36, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedermann, C.J.; Barbieri, V.; Lombardo, S.; Gärtner, T.; Rina, P.; Eisendle, K.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A.; Ausserhofer, D. Health Information Use and Trust: The Role of Health Literacy and Patient Activation in a Multilingual European Region. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. The Health Belief Model and Preventive Health Behavior. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 354–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausserhofer, D.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A.; Marino, P.; Barbieri, V.; Lombardo, S.; Gärtner, T.; Wiedermann, C.J. Sleep Problems and Sleep Quality in the General Adult Population Living in South Tyrol (Italy): A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Clocks Sleep 2025, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorini, C.; Lastrucci, V.; Mantwill, S.; Vettori, V.; Bonaccorsi, G.; Florence Health Literacy Research Group. Measuring Health Literacy in Italy: A Validation Study of the HLS-EU-Q16 and of the HLS-EU-Q6 in Italian Language, Conducted in Florence and Its Surroundings. Annali dell’Istituto Superiore di Sanita 2019, 55, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelikan, J.M.; Ganahl, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Sørensen, K. Measuring Health Literacy in Europe: Introducing the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q). In International Handbook of Health Literacy; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019; pp. 115–138. ISBN 1-4473-4452-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, K.; Pelikan, J.M.; Röthlin, F.; Ganahl, K.; Slonska, Z.; Doyle, G.; Fullam, J.; Kondilis, B.; Agrafiotis, D.; Uiters, E.; et al. Health Literacy in Europe: Comparative Results of the European Health Literacy Survey (HLS-EU). Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenk-Franz, K.; Hibbard, J.H.; Herrmann, W.J.; Freund, T.; Szecsenyi, J.; Djalali, S.; Steurer-Stey, C.; Sönnichsen, A.; Tiesler, F.; Storch, M.; et al. Validation of the German Version of the Patient Activation Measure 13 (PAM13-D) in an International Multicentre Study of Primary Care Patients. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graffigna, G.; Barello, S.; Bonanomi, A. The Role of Patient Health Engagement Model (PHE-Model) in Affecting Patient Activation and Medication Adherence: A Structural Equation Model. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Chung, M.L.; Schuman, D.L.; Biddle, M.J.; Mudd-Martin, G.; Miller, J.L.; Hammash, M.; Schooler, M.P.; Rayens, M.K.; Feltner, F.J.; et al. Psychometric Properties of the Patient Activation Measure in Family Caregivers of Patients with Chronic Illnesses. Nurs. Res. 2023, 72, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. SciPy 2010, 445, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array Programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabold, S.; Perktold, J. Statsmodels: Econometric and Statistical Modeling with Python. SciPy 2010, 7, 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Murali, N.S.; Deao, C.E. Patient Engagement. Prim. Care Clin. Off. Pract. 2019, 46, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krist, A.H.; Tong, S.T.; Aycock, R.A.; Longo, D.R. Engaging Patients in Decision-Making and Behavior Change to Promote Prevention. Inf. Serv. Use 2017, 37, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.; Hibbard, J.H.; Sacks, R.; Overton, V.; Parrotta, C.D. When Patient Activation Levels Change, Health Outcomes And Costs Change, Too. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Milks, M.W.; Liu, X.; Gregory, M.E.; Addison, D.; Zhang, P.; Li, L. mHealth Interventions for Self-Management of Hypertension: Framework and Systematic Review on Engagement, Interactivity, and Tailoring. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2022, 10, e29415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Wang, T.; Hu, P.; Mei, J.; Tang, Z. Chinese Public’s Engagement in Preventive and Intervening Health Behaviors During the Early Breakout of COVID-19: Cross-Sectional Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallant, M.P.; Dorn, G.P. Gender and Race Differences in the Predictors of Daily Health Practices among Older Adults. Health Educ. Res. 2001, 16, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smail, E.; Schneider, K.E.; DeLong, S.M.; Willis, K.; Arrington-Sanders, R.; Yang, C.; Alexander, K.A.; Johnson, R.M. Health Beliefs and Preventive Behaviors Among Adults During the Early COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States: A Latent Class Analysis. Prev. Sci. 2021, 22, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, A.; Lombard, C.; Michelmore, J.; Teede, H. The Effects of Gender and Age on Health Related Behaviors. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller, J.; Schatz, K.; Drexler, H. Gender Influence on Health and Risk Behavior in Primary Prevention: A Systematic Review. J. Public Health 2017, 25, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschaftary, A.; Hess, N.; Hiltner, S.; Oertelt-Prigione, S. The Association between Sex, Age and Health Literacy and the Uptake of Cardiovascular Prevention: A Cross-Sectional Analysis in a Primary Care Setting. J. Public Health 2018, 26, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, W.; Richmond, J.; Mohottige, D.; Yen, I.; Joslyn, A.; Corbie-Smith, G. Medical Mistrust, Racism, and Delays in Preventive Health Screening among African-American Men. Behav. Med. 2019, 45, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolar, S.K.; Wheldon, C.; Hernandez, N.D.; Young, L.; Romero-Daza, N.; Daley, E.M. Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Knowledge and Attitudes, Preventative Health Behaviors, and Medical Mistrust Among a Racially and Ethnically Diverse Sample of College Women. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2015, 2, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, L.D.; Smith, M.A.; Bigman, C.A. Does Discrimination Breed Mistrust? Examining the Role of Mediated and Non-Mediated Discrimination Experiences in Medical Mistrust. J. Health Commun. 2019, 24, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heraclides, A.; Hadjikou, A.; Kouvari, K.; Karanika, Ε.; Heraclidou, I. Low Health Literacy Is Associated with Health-Related Institutional Mistrust beyond Education. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 34, ckae144.1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, D.M.; Larson, J.L.; Zikmund-Fisher, B.J. Associations between Health Literacy and Preventive Health Behaviors among Older Adults: Findings from the Health and Retirement Study. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaby, A.; Friis, K.; Christensen, B.; Rowlands, G.; Maindal, H.T. Health Literacy Is Associated with Health Behaviour and Self-Reported Health: A Large Population-Based Study in Individuals with Cardiovascular Disease. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2017, 24, 1880–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, G.Y.; Son, H. Associations between Health Literacy, Cancer-Related Knowledge, and Preventive Health Behaviors in Community-Dwelling Korean Adults. J. Health Commun. 2017, 22, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, B.R.; Lindly, O. A Rapid Evidence Review on Health Literacy and Health Behaviors in Older Populations. Aging Health Res. 2024, 4, 100195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Segalowitz, N.; Voloshyn, A.; Chamoux, E.; Ryder, A.G. Language Barriers to Healthcare for Linguistic Minorities: The Case of Second Language-Specific Health Communication Anxiety. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drolet, M.; Savard, J.; Benoît, J.; Arcand, I.; Savard, S.; Lagacé, J.; Lauzon, S.; Dubouloz, C.-J. Health Services for Linguistic Minorities in a Bilingual Setting: Challenges for Bilingual Professionals. Qual. Health Res. 2014, 24, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaci, V.; Ramos, J.; Boyce, E. A Model for Delivery of Mental Health Services to Spanish-Speaking Minorities. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1974, 44, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, P.; Iniguez, R.; Park, Y.S.; Girotti, J.A. Bilingual Diabetes Workshop to Improve Latinx Care. Clin. Teach. 2022, 19, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, L.; Kisa, S.; Lukasse, M.; Flaathen, E.M.; Mortensen, B.; Karlsen, E.; Garnweidner-Holme, L. Cultural Sensitivity in Interventions Aiming to Reduce or Prevent Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy: A Scoping Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2023, 24, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Hamid, M.O. Bilingualism as a Resource: Language Attitudes of Vietnamese Ethnic Minority Students. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2018, 19, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, B.C.; Cox, A.; Duran, G.; Kerremans, K.; Banning, L.K.; Lahdidioui, A.; van den Muijsenbergh, M.; Schinkel, S.; Sungur, H.; Suurmond, J.; et al. Mitigating Language and Cultural Barriers in Healthcare Communication: Toward a Holistic Approach. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 2604–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, D.S.-Y.; Ku, B.H.-B. Health-Seeking, Intercultural Health Communication, and Health Outcomes: An Intersectional Study of Ethnic Minorities’ Lived Experiences. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaña, D. Local Voices on Health Care Communication Issues and Insights on Latino Cultural Constructs. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2020, 42, 300–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, L.E.; Cervantes, L.; Havranek, E. Barriers in Healthcare for Latinx Patients with Limited English Proficiency—A Narrative Review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2023, 38, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafari, O.; Bahrami-Hessari, M.; Norton, J.; Parmar, R.; Hudson, M.; Ndegwa, L.; Agyapong-Badu, S.; Asante, K.P.; Alwan, N.A.; McDonough, S.; et al. Building Trust and Increasing Inclusion in Public Health Research: Co-Produced Strategies for Engaging UK Ethnic Minority Communities in Research. Public Health 2024, 233, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, N.K.; Pieh, M.C.; Dixon, L.; Guarnaccia, P.; Alegría, M.; Lewis-Fernández, R. Clinician Descriptions of Communication Strategies to Improve Treatment Engagement by Racial/Ethnic Minorities in Mental Health Services: A Systematic Review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ausserhofer, D.; Wiedermann, W.; Becker, U.; Vögele, A.; Piccoliori, G.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Engl, A. Health Information-Seeking Behavior Associated with Linguistic Group Membership: Latent Class Analysis of a Population-Based Cross-Sectional Survey in Italy, August to September 2014. Arch. Public Health 2022, 80, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perloff, R.M.; Bonder, B.; Ray, G.B.; Ray, E.B.; Siminoff, L.A. Doctor-Patient Communication, Cultural Competence, and Minority Health: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives. Am. Behav. Sci. 2006, 49, 835–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palu, E.; McBride, K.A.; Simmons, D.; Thompson, R.; Cavallaro, C.; Cooper, E.; Felila, M.; MacMillan, F. Adequacy of Health Message Tailoring for Ethnic Minorities: Pasifika Communities in Sydney, Australia, during COVID-19. Health Promot. Int. 2024, 39, daad197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinzadeh, H.; Downie, S.; Shnaigat, M. Effectiveness of Health Literacy- and Patient Activation-Targeted Interventions on Chronic Disease Self-Management Outcomes in Outpatient Settings: A Systematic Review. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2022, 28, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, S.; Kendall, E.; See, L. The Effectiveness of Culturally Appropriate Interventions to Manage or Prevent Chronic Disease in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Communities: A Systematic Literature Review. Health Soc. Care Community 2011, 19, 225–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | n (Weighted) | GHP-16 Score 1 | Comparison | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | 95% CI Lower 2 | 95% CI Upper 2 | p-Value 3 | Effect Size 4 | |||

| Gender | Male | 1026 | 50.7 | 50.67 | 50.70 | <0.001 | 0.597 |

| Female | 1064 | 53.3 | 54.67 | 56.00 | |||

| Age group | 18–34 years | 496 | 50.7 | 49.33 | 52.00 | <0.001 | 0.026 |

| 35–54 years | 683 | 50.7 | 52.00 | 53.33 | |||

| 55–99 years | 912 | 56.0 | 54.67 | 56.00 | |||

| Residence | Rural | 1665 | 50.7 | 53.33 | 53.33 | 0.001 | −0.117 |

| Urban | 425 | 53.3 | 53.33 | 56.00 | |||

| Education | Middle school | 441 | 50.7 | 52.00 | 53.33 | <0.001 | 0.032 |

| Vocational school | 666 | 49.3 | 50.67 | 52.00 | |||

| High school | 545 | 52.0 | 53.33 | 54.67 | |||

| University | 1885 | 50.7 | 53.33 | 53.33 | |||

| Citizenship | Italian | 205 | 53.3 | 49.33 | 56.00 | 0.559 | 0.071 |

| Other | 205 | 53.3 | 34.47 | 68.07 | |||

| Language | German | 1330 | 50.7 | 52.00 | 53.33 | <0.001 | 0.015 |

| Italian | 480 | 53.3 | 54.67 | 56.00 | |||

| Other | 280 | 50.7 | 49.33 | 54.67 | |||

| Lives alone | No | 1718 | 52.0 | 53.33 | 53.33 | 0.545 | 0.005 |

| Yes | 372 | 52.0 | 53.33 | 54.67 | |||

| Works in health or social sector | No | 1874 | 50.7 | 53.33 | 53.33 | <0.001 | −0.353 |

| Yes | 215 | 54.7 | 54.67 | 57.33 | |||

| Self-rated health status | High | 1447 | 54.7 | 37.33 | 69.33 | 0.001 | 0.010 |

| Middle | 511 | 53.3 | 36.00 | 69.33 | |||

| Low | 131 | 53.3 | 28.57 | 67.43 | |||

| Health literacy (HLS-EU_Q16) | Inadequate | 266 | 50.7 | 50.67 | 53.33 | <0.001 | 0.052 |

| Problematic | 559 | 52.0 | 52.00 | 53.33 | |||

| Sufficient | 824 | 53.3 | 54.67 | 56.00 | |||

| Unknown/missing | 441 | 48.0 | 49.33 | 52.00 | |||

| Patient activation (PAM-10) | Disengaged and overwhelmed | 336 | 49.3 | 49.33 | 50.67 | <0.001 | 0.079 |

| Becoming aware but still struggling | 888 | 50.7 | 52.00 | 53.33 | |||

| Taking action | 490 | 50.7 | 53.33 | 54.67 | |||

| Maintaining behaviors and pushing further | 377 | 56.0 | 57.33 | 60.00 | |||

| Chronic disease | No | 1357 | 50.7 | 52.00 | 53.33 | 0.001 | −0.171 |

| Yes | 733 | 53.3 | 53.33 | 54.67 | |||

| Number of chronic diseases | 1 | 496 | 53.3 | 53.33 | 54.67 | 0.022 | 0.006 |

| 2 | 162 | 53.3 | 53.33 | 54.67 | |||

| 3 | 60 | 52.0 | 52.00 | 56.00 | |||

| 4 | 10 | 53.3 | 48.00 | 61.33 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 53.3 | 44.00 | 58.67 | |||

| Variable | Regression Coefficient ß | 95% CI [Lower; Upper] | Std. Error | t-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| const | 6.532 | [5.885; 7.178] | 0.33 | 19.818 | <0.001 |

| Mistrust_Index | −0.05 | [−0.09; −0.009] | 0.021 | −2.42 | 0.016 |

| Female (vs. Male) | 1.183 | [1.018; 1.347] | 0.084 | 14.097 | <0.001 |

| Age (in years) | 0.025 | [0.02; 0.030] | 0.003 | 9.306 | <0.001 |

| Education (vs. middle school or lower) | |||||

| Vocational school | 0.363 | [0.135; 0.592] | 0.116 | 3.119 | 0.002 |

| High school | 0.737 | [0.488; 0.987] | 0.127 | 5.798 | <0.001 |

| University | 1.130 | [0.855; 1.406] | 0.14 | 8.046 | <0.001 |

| Language (vs. German) | |||||

| Italian | 0.372 | [0.177; 0.567] | 0.1 | 3.738 | <0.001 |

| Other | −0.193 | [−0.48; 0.095] | 0.147 | −1.312 | 0.190 |

| Lives alone (vs. no) | −0.130 | [−0.339; 0.088] | 0.107 | −1.214 | 0.225 |

| Works in health or social sector (vs. no) | 0.016 | [−0.258; 0.291] | 0.14 | 0.117 | 0.907 |

| HLS-EU-Q16 (vs. problematic) 1 | |||||

| Inadequate | 0.237 | [−0.046; 0.520] | 0.144 | 1.645 | 0.100 |

| Sufficient | 0.518 | [0.238; 0.798] | 0.143 | 3.627 | <0.001 |

| Missing/unknown | −0.126 | [−0.423; 0.172] | 0.152 | −0.827 | 0.408 |

| PAM-10 (vs. disengaged and overwhelmed) 1 | |||||

| Becoming aware | 0.603 | [0.360; 0.846] | 0.124 | 4.86 | <0.001 |

| Taking action | 0.875 | [0.603; 1.147] | 0.139 | 6.315 | <0.001 |

| Maintaining | 1.61 | [1.319; 1.902] | 0.149 | 10.823 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Regression Coefficient ß | 95% CI [Lower; Upper] | Std. Error | t-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| const | 5.614 | [5.065; 6.164] | 0.28 | 20.038 | <0.001 |

| Female (vs. male) | 1.239 | [1.069; 1.410] | 0.087 | 14.283 | <0.001 |

| Age (in years) | 0.026 | [0.021; 0.032] | 0.003 | 9.725 | <0.001 |

| Lives alone (vs. no) | −0.156 | [−0.374; 0.061] | 0.111 | −1.411 | 0.158 |

| Language (vs. German) | |||||

| Italian | 0.377 | [0.172; 0.581] | 0.104 | 3.614 | <0.001 |

| Other | −0.249 | [−0.542; 0.044] | 0.149 | −1.664 | 0.096 |

| Education (vs. middle school or lower) | |||||

| Vocational school | 0.398 | [0.162; 0.634] | 0.12 | 3.309 | 0.001 |

| High school | 0.828 | [0.569; 1.087] | 0.132 | 6.272 | <0.001 |

| University | 1.188 | [0.904; 1.473] | 0.145 | 8.198 | <0.001 |

| Works in health or social sector (vs. no) | 0.028 | [−0.255; 0.311] | 0.144 | 0.194 | 0.846 |

| HLS-EU-Q16 (vs. problematic) 1 | |||||

| Inadequate | 0.321 | [0.037; 0.606] | 0.145 | 2.215 | 0.027 |

| Sufficient | 0.548 | [0.268; 0.828] | 0.143 | 3.84 | <0.001 |

| Missing/unknown | −0.19 | [−0.488; 0.108] | 0.152 | −1.252 | 0.211 |

| PAM-10 (vs. disengaged and overwhelmed) 1 | |||||

| Becoming aware | 0.657 | [0.413; 0.900] | 0.124 | 5.29 | <0.001 |

| Taking action | 1.011 | [0.737; 1.284] | 0.14 | 7.241 | <0.001 |

| Maintaining | 1.739 | [1.439; 2.039] | 0.153 | 11.353 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ausserhofer, D.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Barbieri, V.; Lombardo, S.; Gärtner, T.; Eisendle, K.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A. Preventive Health Behavior and Readiness for Self-Management in a Multilingual Adult Population: A Representative Study from Northern Italy. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070240

Ausserhofer D, Wiedermann CJ, Barbieri V, Lombardo S, Gärtner T, Eisendle K, Piccoliori G, Engl A. Preventive Health Behavior and Readiness for Self-Management in a Multilingual Adult Population: A Representative Study from Northern Italy. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(7):240. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070240

Chicago/Turabian StyleAusserhofer, Dietmar, Christian J. Wiedermann, Verena Barbieri, Stefano Lombardo, Timon Gärtner, Klaus Eisendle, Giuliano Piccoliori, and Adolf Engl. 2025. "Preventive Health Behavior and Readiness for Self-Management in a Multilingual Adult Population: A Representative Study from Northern Italy" Nursing Reports 15, no. 7: 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070240

APA StyleAusserhofer, D., Wiedermann, C. J., Barbieri, V., Lombardo, S., Gärtner, T., Eisendle, K., Piccoliori, G., & Engl, A. (2025). Preventive Health Behavior and Readiness for Self-Management in a Multilingual Adult Population: A Representative Study from Northern Italy. Nursing Reports, 15(7), 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070240