Nursing Students’ Perceptions of Clinical Debriefing TALK©: A Qualitative Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Patient Safety Education Among Nursing Students

1.2. TALK© Debriefing

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Research Team

2.3. Setting

2.4. Participants

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

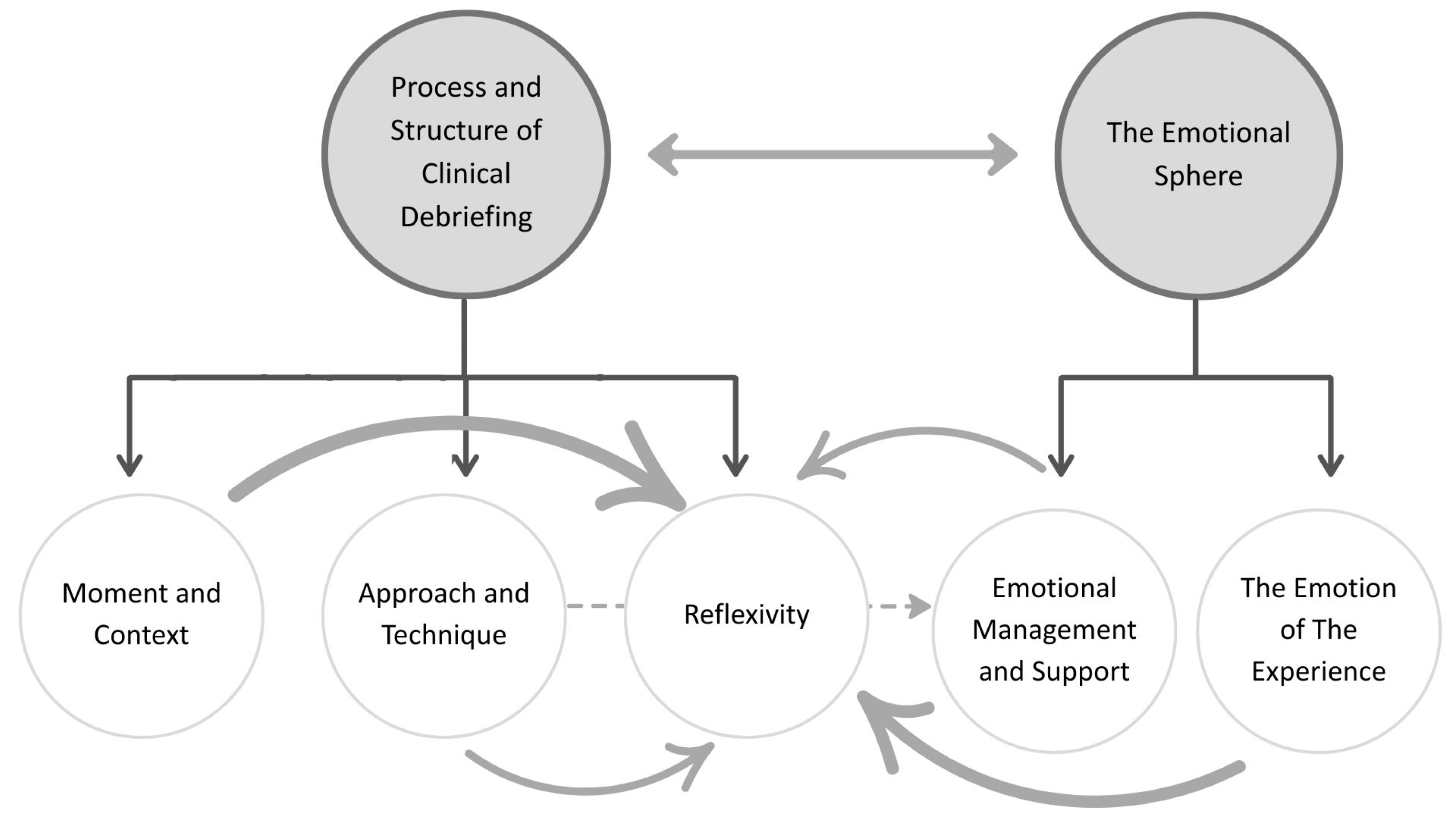

3.1. Process and Structure of Clinical Debriefing

3.1.1. Reflexivity

P19: if you experience a situation and it is a situation that impacts you in some way, good or bad, innately you are already going to reflect on that situation [...]. Now, doing a debriefing dedicated to that specifically is going to help you more than doing it by yourself in a natural way, it is giving you an objective, which is to look for points of improvement and to analyze the situation.

P26: if you are the one who decides it is because you want to draw conclusions from these things or solutions and learn. I think you are more open to reflect.

P5: It is as if you have experienced something at one moment and you are going to reflect on it at a different moment. You are going to better integrate that knowledge and the memories you have.

P26: With limited knowledge, you can’t engage in deeper reflection.

P6: In a debriefing, it’s not the person who knows the most who should speak the most—especially when the goal is to learn how to manage patient care effectively in an interdisciplinary team. Everyone needs to participate equally.

P20: We discussed a case in the operating room. There was laparoscopic digestive surgery, and they ended up sectioning the hepatic artery, and then there was massive bleeding, and we analyzed what we thought we could have done or what could have been done to avoid it or how the thing flowed when it happened.

P13: You start developing more critical thinking when you become aware of the mistakes you make. When you continue doing clinical practice, you stop and ask yourself… why am I doing this, and why not something better? You train your mind not to do things automatically.

P6: What touches you up close is engraved in your heart, isn’t it? That is so. Others will also learn something, but it won’t be so engraved, it won’t remind you of that patient, it may remind you of what we talked about in the debriefing.

P5: If you share something that happened to you, you might feel more exposed—maybe, I don’t know, it depends on the situation—but possibly more insecure depending on what actually happened.

P17: For me, it was a moment that provided space to express if you have any other concerns, and to know that you can count on others who are in the same situation as you. And to be able to solve that problem from different perspectives. And in that way, you can find a practical solution.

3.1.2. Approach and Technique

P6: It is a good way to get to the end of the debriefing, which is to look for that solution. It allows you to have a much more holistic, much more general view of the case, and I think that also allows you to analyze it better, reflect better and draw better conclusions. So, I think it is a very good tool.

P10: I think they were guiding us with the TALK tool, because otherwise... we would have gone off track. But it wasn’t super rigid—like, if we were on the ‘L’ step, we weren’t forbidden from going back.

P19: I think it has to be someone external, neutral, and who handles the tool well, for it to be effective.

P5: You are with them every afternoon. So, in the end, we have that feeling, we are comfortable there. [...] As I already had the previous experience of the ICU... better, you get to know the tool better and you follow it more, you are more comfortable.

P5: If we do not choose the topics to talk about and one is imposed on us, maybe we are not so willing to comment on that case or maybe we have not experienced anything similar.

P8: Sometimes you don’t bring up the topic yourself… for whatever reason, and if the facilitators know what happened and that it’s useful to talk about it, it might be important.

P22: They were questions to make you think about why, and not to judge you or question you, but to reflect.

P26: In the end, since we knew them, it made it easier—so even if they asked a question that might have made us uncomfortable, because we already knew them, it wasn’t hard to answer, you didn’t second-guess your response—you just answered.

3.1.3. Moment and Context

P6: Not in the heat of the moment. Especially if it has to be something negative. I think that after... after a week or so, or even a few days, that’s when it’s better. [...] I mean, out of the storm everything is much clearer.

P7: the sooner you talk about it, the sooner other people can also realize that I can also make a mistake in that and you can also prevent other people’s mistakes.

P21: there are differences because, well, each service is different. So, well, debriefing? I think that the dynamics of debriefing would not really change. It would simply change because of the content or errors that may occur, which may be more serious.

P19: In the end, I think that the ICU is an internship where students have a lot of relationship with the rest of the classmates, so you develop more confidence. In other internships where you may not have as much connection, debriefing can be difficult, as in the operating room.

P5: But the fact that it is a first time is like you have never experienced anything like it before. So that marks you, you are not used to it, and it impacts you. And you take that with you. And it’s important, it’s like you learn more from it.

P6: Clinical debriefing has a real objective for the well-being of the patient and to get something out of it. What we share during snack breaks is often not a reflective process, it is an absolute avoidance process.

P21: Let’s see, it could be done in the second... in the third and fourth year to see the evolution. I think it would never hurt. But now that’s it, you’re on the edge, you’re on the edge of student life and what I’ve learned in it, and the abyss of... “hello, let’s see what comes to me.”

3.2. The Emotional Sphere

3.2.1. The Emotion of the Experience

P5: I feel that learning is more visible, i.e., you assimilate it more if you relate it to a feeling that it has produced in you, it is more marked.

P7: if something goes wrong in a simulation it doesn’t affect me, because I say, well, I did it wrong, but nobody got hurt. [...] In the clinical debriefing, if we comment on the fact that I have inadvertently made a medication error, then I know that I will get more involved.

3.2.2. Emotional Management and Support

P6: I felt a bit like saying, it wasn’t that hard either [...] So, on the one hand, learning, and on the other hand, it was like, you could have done better. Like feeling, it’s not like feeling dumb, but a little bit of guilt.

P19: Yes, there was some issue that could... could lead to that because we talked about medication errors and things like that. But other than that burden of guilt that already comes with the issue innately, no, I didn’t feel judged or anything like that.

P20: I think if our care coach is the one leading the debriefing, you hold back a little… you worry more about being judged, especially if you didn’t handle something well.

P8: I think that with the group I had it was minimized, that is, if P6 could feel guilty, then the rest of the colleagues made him feel that he was not guilty.

P15: It is very hard to open up and say what we feel, and thanks to this you can say, well, look, I was so scared that I ran away. It makes it easier to talk. You don’t always have the opportunity or the space to express your feelings.

P10: Well, a little bit of what my classmates have said about, well that, by talking about it and so on, knowing that it could not only have happened to you, and also feeling supported and listened to a little bit.

4. Discussion

4.1. Process and Structure of Clinical Debriefing: Reflexivity, Approach and Technique, and Moment and Context

4.2. The Emotional Sphere: The Emotion of Experience and Emotional Management and Support

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COREQ | Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research |

| ER | Emergency Room |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| OR | Operating Room |

| SRQR | Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Oh, S.; Park, J. A literature review of simulation-based nursing education in Korea. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szyld, D.; Arriaga, A.F.; León-Castelao, E. El debriefing clínico, retos y oportunidades en el ámbito asistencial; aprendizaje en la reflexión colectiva para mejorar los sistemas sanitarios y la colaboración interprofesional. Rev. Latinoam. Simul. Clín. 2021, 3, 69–73. Available online: https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/simulacion/rsc-2021/rsc212d.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Patient Safety: Global Action on Patient Safety–Report by the Director-General (Document A74/13). 2021. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA74/A74_13-en.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Edwards, J.J.; Wexner, S.; Nichols, A. Debriefing for Clinical Learning; PSNet; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2021. Available online: https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/debriefing-clinical-learning (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Imperio, M.; Ireland, K.; Xu, Y.; Esteitie, R.; Tan, L.D.; Alismail, A. Clinical team debriefing post-critical events: Perceptions, benefits, and barriers among learners. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1406988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Navarro, C.; Leon-Castelao, E.; Hadfield, A.; Pierce, S.; Szyld, D. Clinical debriefing: TALK© to learn and improve together in healthcare environments. Trends Anaesth. Crit. Care 2021, 40, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Medical Simulation. Debriefing Assessment for Simulation in Healthcare (DASH)©; Hospital Virtual Valdecilla: Santander, Spain, 2016; Available online: https://harvardmedsim.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Manual-de-trabajo-EDSS-completo-2016-agosto.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Escribano Sánchez, G.; Leal Costa, C.; García Sánchez, A. Debriefing y Estrategias de Aprendizaje. Análisis Comparativo Entre dos Estilos de Análisis Reflexivo en Estudiantes de Enfermería que Aprenden con Simulación Clínica. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Católica de Murcia, Guadalupe, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Torkaman, M.; Sabzi, A.; Farokhzadian, J. The effect of patient safety education on undergraduate nursing students’ patient safety competencies. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 2020, 42, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddison, M. Improving patient safety through nurse education. Br. J. Nurs. 2024, 33, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, R.C.; Bezerra, M.A.R.; Martins, B.M.B.; Nunes, B.M.V.T. Enseñanza de la seguridad del paciente en enfermería: Revisión integrativa. Enferm. Glob. 2021, 20, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundt, A.S.; Gjeraa, K.; Spanager, L.; Petersen, S.S.; Dieckmann, P.; Østergaard, D. Okay, let’s talk-short debriefings in the operating room. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaga, A.F.; Szyld, D.; Pian-Smith, M.C.M. Real-time debriefing after critical events: Exploring the gap between principle and reality. Anesthesiol. Clin. 2020, 38, 801–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications, 6th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fàbregues, S.; Fetters, M.D. Fundamentals of case study research in family medicine and community health. Fam. Med. Community Health 2019, 7, e000074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, V.E.J.; Weiler, C.C. Los estudios de casos como enfoque metodológico. ACADEMO Rev. Investig. Cienc. Soc. Humanid. 2016, 3, 1–11. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/5757749.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. Paradigmas y Perspectivas en Disputa: Manual de Investigación Cualitativa, 1st ed.; Gedisa: Barcelona, España, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación Jiménez Díaz Nursing School. Prácticas y Laboratorio de Simulación; Fundación Jiménez Díaz. Available online: https://www.fjd.es/escuela-enfermeria/es/estudiantes/practicas-laboratorio-simulacion (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- España. Real Decreto 581/2017, de 9 de junio, por el que se regulan las cualificaciones profesionales en el ámbito de la Unión Europea. Boletín Oficial del Estado 2017, 138, 48166–48179. Available online: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2017/06/10/pdfs/BOE-A-2017-6586.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2021, 13, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Chen, M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner-Bowker, D.M.; Lamoureux, R.E.; Stokes, J.; Litcher-Kelly, L.; Galipeau, N.; Thorsen, H.; McKown, D.; DeRosa, M.A.; Lenderking, W.R. Informing a priori sample size estimation in qualitative concept elicitation interview studies for clinical outcome assessment instrument development. Value Health 2018, 21, 839–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. Declaración de Helsinki de la AMM: Principios éticos para las Investigaciones Médicas con Participantes Humanos; 75.ª Asamblea General: Helsinki, Finlandia, 2024; Available online: https://www.wma.net/es/policies-post/declaracion-de-helsinki-de-la-amm-principios-eticos-para-las-investigaciones-medicas-en-seres-humanos/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Dewey, J. Democracia y Educación: Una Introducción a la Filosofía de la Educación; Simón y Brown: Madrid, España, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, G. Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods (Practice-Based Professional Learning Paper 52); Oxford Brookes University, Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development: Oxford, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Johns, C. Guided Reflection: Advancing Practice; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D.A. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Barchard, F. Exploring the role of reflection in nurse education and practice. Nurs. Stand. 2022, 37, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, R.B.T.; Hoe, K.W.B.; Zheng, H. A systematic review of the outcomes, level, facilitators, and barriers to deep self-reflection in public health higher education: Meta-analysis and meta-synthesis. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 938224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, N.; Murphy, C.E. Case reports, reflective practice and learning to succeed. Anesth. Rep. 2023, 11, e12212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galligan, M.M.; Goldstein, L.; Garcia, S.M.; Kellom, K.; Wolfe, H.A.; Haggerty, M.; DeBrocco, D.; Barg, F.K.; Friedlaender, E. A qualitative study of resident experiences with clinical event debriefing. Hosp. Pediatr. 2022, 12, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Ekebergh, M. Lifeworld-based reflection and learning: A contribution to the reflective practice in nursing and nursing education. Reflect. Pract. 2007, 8, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, L. Reflecting on ‘Reflective Practice’; Practice-Based Professional Learning Paper 52; The Open University: Milton Keynes, UK, 2008; Available online: https://oro.open.ac.uk/68945/ (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Berterö, C. Reflection in and on nursing practices: How nurses reflect and develop knowledge and skills during their nursing practice. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2010, 3, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- INACSL Standards Committee; Decker, S.; Alinier, G.; Crawford, S.B.; Gordon, R.M.; Jenkins, D.; Wilson, C. Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best Practice™: The debriefing process. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2021, 58, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwatoyin, F.E. Reflective practice: Implication for nurses. IOSR J. Nurs. Health Sci. 2015, 4, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epp, S. The Value of Reflective Journaling in Undergraduate Nursing Education: A Literature Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008, 45, 1379–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twigg, S. Clinical event debriefing: A review of approaches. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2020, 32, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Navarro, C.; Enjo-Pérez, I.; León-Castelao, E.; Hadfield, A.; Nicolás-Arfelis, J.M.; Castro-Rebollo, P. Implementation of the TALK© clinical self-debriefing tool in operating theatres: A single-centre interventional study. Br. J. Anaesth. 2024, 133, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathu, C. Facilitators and Barriers of Reflective Learning in Postgraduate Medical Education: A Narrative Review. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2022, 9, 23821205221096106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadpour, N.; Shariati, A.; Poodineh Moghadam, M. Effect of Narrative Writing Based on Gibbs’ Reflective Model on the Empathy and Communication Skills of Nursing Students. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Jiang, W.J.; Zhao, R.P. Application Effect of Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory in Clinical Nursing Teaching of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 20552076221138313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, D.A. Aprendizaje Experiencial: La Experiencia como Fuente de Aprendizaje y Desarrollo, 2nd ed.; Pearson Educación: Madrid, España, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sandars, J. The Use of Reflection in Medical Education: AMEE Guide No. 44. Med. Teach. 2009, 31, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J.W.; Simon, R.; Rivard, P.; Dufresne, R.L.; Raemer, D.B. Debriefing with Good Judgment: Combining Rigorous Feedback with Genuine Inquiry. Anesthesiol. Clin. 2007, 25, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fey, M.K.; Roussin, C.J.; Rudolph, J.W.; Morse, K.J.; Raemer, D.B.; Kolbe, M. Teaching, Coaching, or Debriefing With Good Judgment: A Roadmap for Implementing “With Good Judgment” across the SimZones. Adv. Simul. 2022, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C.; Lei, Z. Psychological Safety: The History, Renaissance, and Future of an Interpersonal Construct. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, N.R.; Abouarabi, Y.B.; Chen, J.; Hansen, S.; Velmurugan, G.; Fink, T.; Lyngdorf, N.E.; Guerra, A.; Du, X. First-Year University Students’ Perspectives on Their Psychological Safety in PBL Teams. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Peng, Y. The Impact of Team Psychological Safety on Employee Innovative Performance: A Study with Communication Behavior as a Mediator Variable. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0306629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, J.; Reguant, M.; Tort, G.; Canet, O. Developing Reflective Competence between Simulation and Clinical Practice through a Learning Transference Model: A Qualitative Study. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 92, 104520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, B.; Bessell, N.; Murphy, S.; Hartigan, I. Nursing and Speech and Language Students’ Perspectives of Reflection as a Clinical Learning Strategy in Undergraduate Healthcare Education: A Qualitative Study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 57, 103251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCloughen, A.; Levy, D.; Johnson, A.; Nguyen, H.; McKenzie, H. Nursing Students’ Socialisation to Emotion Management during Early Clinical Placement Experiences: A Qualitative Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2508–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, E.; Olsen, L.; Denison, J.; Zerin, I.; Reekie, M. “I Will Go If I Don’t Have to Talk”: Nursing Students’ Perceptions of Reflective, Debriefing Discussions and Intent to Participate. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 70, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plowe, K. Increasing Resiliency: A Focus for Clinical Conferencing/Group Debriefing in Nursing Education. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 49, 102882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elarousy, W.; de Beer, J.; Alnajjar, H. Exploring the Experiences of Nursing Students during Debriefing: A Qualitative Study. Am. J. Nurs. Res. 2019, 7, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, J.S.; Thapa, P.; Micheal, S.; Dune, T.; Lim, D.; Alford, S.; Mistry, S.K.; Arora, A. The Impact of a Peer Support Program on the Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Postgraduate Health Students during COVID-19: A Qualitative Study. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, R.; Singaram, V.S. Self and Peer Feedback Engagement and Receptivity among Medical Students with Varied Academic Performance in the Clinical Skills Laboratory. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, E.C.; Smith, S.E.; Tallentire, V.; Blair, S. Systematic Review of Clinical Debriefing Tools: Attributes and Evidence for Use. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2024, 33, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topic to Explore | Question |

|---|---|

| Feelings and emotions | How did you feel during the debriefing? How does it influence your comfort that the debriefing is not of a simulated situation? How did you feel during the debriefing when speaking in front of other people? How do you think feelings and emotions may vary depending on whether or not you are the protagonist of the incidents you discussed? |

| Relationship established between classmates | How did you feel about your colleagues during the debriefing? How did being with the same colleagues from your clinical internship influence your experience during the debriefing? How was your relationship during the internship and how did it influence the development of the debriefing? |

| Facilitators’ role | What is your opinion about how the facilitators handled the debriefing? If the facilitators had begun by sharing a challenging professional experience of their own as nurses, how do you think that might have influenced the debriefing process? Did you feel guilty or judgmental at any point, and can you tell me what made you feel/not feel that way? If you did feel judged or guilty, what changes would you suggest in how the debriefing is conducted to reduce or prevent that feeling? How did you experience the fact that the facilitators were people you already knew? How did it affect the debriefing that the facilitators presented themselves as “non-teachers”? What impact did it have on the debriefing that the facilitators were not directly involved in or present during the incidents being discussed? How do you think you would feel doing the debriefing with your assistive tutors? |

| Time for debriefing | Considering that the debriefing did not take place on the same day as the incidents you mentioned, when do you think is the best time to carry out this type of debriefing and why? What differences do you think there are between doing this debriefing in one service or another? |

| Perception about the TALK© tool | What is your opinion about the TALK© tool that was used to carry out the debriefing? What differences do you find between this debriefing and the conversations you have with each other during the breaks? What do you think about the fact that you were the ones who chose the topics to talk about in the debriefing? How do you think it would have influenced you if the topics had been imposed by the facilitators? Do you find any differences between the educational debriefing you have done in simulation and the clinical debriefing? How do you think the fact that the debriefing was based on a real situation you experienced—rather than a simulated one—affected your experience? |

| Impact of debriefing with a good judgment approach on student | How did you experience the questions asked by the facilitators? What was your feeling when the facilitators asked you about your emotions and feelings when talking about the incidents? How did that influence the debriefing? |

| Issues covered in the clinical debriefing | What problems were you able to detect in the above incidents through the clinical debriefing? Did you talk about all the issues you wanted to talk about? |

| Focus Group | Participants | Duration (Minutes) |

|---|---|---|

| Intensive Care Unit (ICU) | 11 participants | 130 |

| Operating Room (OR) | 6 participants | 86 |

| Emergency Room (ER) | 10 participants | 90 |

| Participant (P) | Sex | Age | Clinical Rotation Unit/Clinical Debriefing Session |

|---|---|---|---|

| P2 | Female | 26 | OR |

| P5 | Female | 22 | ER and ICU |

| P6 | Male | 22 | ER |

| P7 | Female | 22 | ER |

| P8 | Female | 22 | ER |

| P9 | Female | 22 | ER |

| P10 | Female | 22 | ER |

| P11 | Female | 22 | ER |

| P12 | Female | 25 | ER |

| P13 | Female | 23 | ER |

| P14 | Female | 22 | ER |

| P15 | Female | 49 | OR |

| P16 | Female | 22 | OR |

| P17 | Female | 36 | OR |

| P18 | Female | 22 | OR |

| P19 | Male | 22 | OR and ICU |

| P20 | Female | 22 | OR |

| P21 | Female | 22 | ICU |

| P22 | Female | 22 | ICU |

| P23 | Female | 22 | ICU |

| P24 | Female | 22 | ICU |

| P25 | Female | 23 | ICU |

| P26 | Female | 22 | ICU |

| P27 | Female | 22 | ICU |

| P28 | Female | 22 | ICU |

| P29 | Female | 22 | ICU |

| P30 | Male | 22 | ICU |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Tejerina, B.; Pérez-Corrales, J.; Palacios-Ceña, D.; Abad-Valle, J.; Gómez, P.R.; González-Toledo, B.; García-Carpintero Blas, E.; Garrigues-Ramón, M. Nursing Students’ Perceptions of Clinical Debriefing TALK©: A Qualitative Case Study. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15060194

González-Tejerina B, Pérez-Corrales J, Palacios-Ceña D, Abad-Valle J, Gómez PR, González-Toledo B, García-Carpintero Blas E, Garrigues-Ramón M. Nursing Students’ Perceptions of Clinical Debriefing TALK©: A Qualitative Case Study. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(6):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15060194

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Tejerina, Belén, Jorge Pérez-Corrales, Domingo Palacios-Ceña, Jose Abad-Valle, Paloma Rodríguez Gómez, Beatriz González-Toledo, Eva García-Carpintero Blas, and Marta Garrigues-Ramón. 2025. "Nursing Students’ Perceptions of Clinical Debriefing TALK©: A Qualitative Case Study" Nursing Reports 15, no. 6: 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15060194

APA StyleGonzález-Tejerina, B., Pérez-Corrales, J., Palacios-Ceña, D., Abad-Valle, J., Gómez, P. R., González-Toledo, B., García-Carpintero Blas, E., & Garrigues-Ramón, M. (2025). Nursing Students’ Perceptions of Clinical Debriefing TALK©: A Qualitative Case Study. Nursing Reports, 15(6), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15060194