Understanding Needlestick Injuries Among Estonian Nurses: Prevalence, Contributing Conditions, and Safety Awareness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and NSI Data

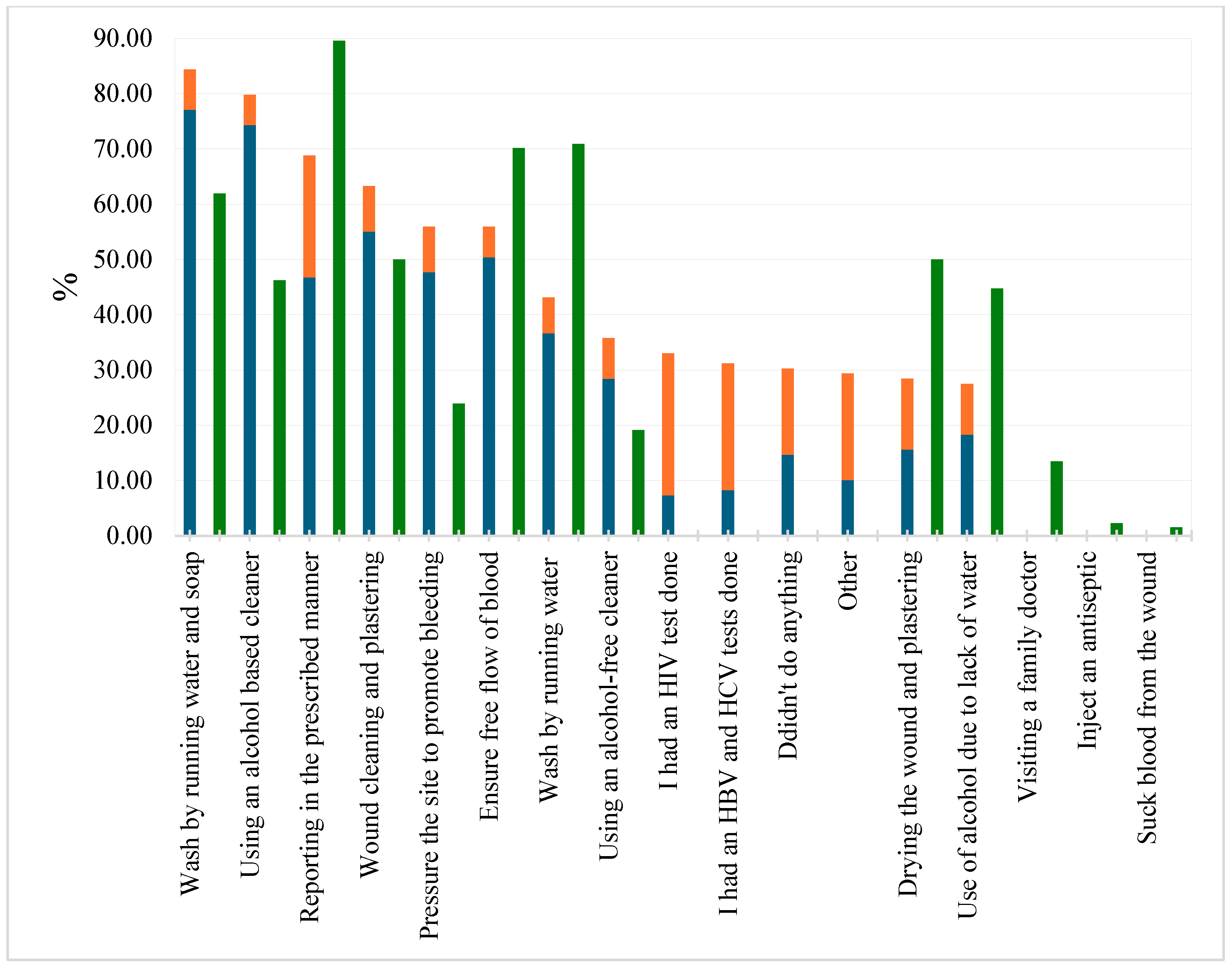

3.2. The Behavior of Nurses After Real NSIs and Opinions on the Actions Needed

3.3. Reasons for Not Reporting NSIs

3.4. Nurses’ Views on the Prevention of Major Bloodborne Diseases

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NSI | Needlestick injury |

| PEP | Post-exposure prophylaxis |

| CDC | The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

References

- Denault, D.; Gardner, H. OSHA Bloodborne Pathogen Standards; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025; (Updated 20 July 2023). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570561/ (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- King, K.C.; Strony, R. Needlestick; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025; (Updated 1 May 2023). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493147/ (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Dağci, M.; Yazici Sayin, Y. Needlestick and sharps injuries among operating room nurses, reasons and precautions. Bezmialem Sci. 2021, 9, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouya, S.; Balouchi, A.; Rafiemanesh, H.; Amirshahi, M.; Dastres, M.; Moghadam, M.P.; Behnamfar, N.; Shyeback, M.; Badakhsh, M.; Allahyari, J.; et al. Global prevalence and device related causes of needle stick injuries among health care workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Glob. Health 2020, 86, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalkareem, J.S.; Thaeer Hammid, A.; Turgunpulatovich Daminov, B.; Kadhem Abid, M.; Lateef Al-Awsi, G.R.; Afra, A.; Ekrami, H.A.; Ameer Muhammed, F.A.; Mohammadi, M.J. Investigation ways of causes needle sticks injuries, risk factors affecting on health and ways to preventive. Rev. Environ. Health 2023, 38, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onubogu, C.U.; Nwaneli, E.I.; Chigbo, C.G.; Egbuniwe, M.C.; Egeonu, R.O.; Chukwurah, S.N.; Maduekwe, N.P.; Onyeyili, I.; Umobi, C.P.; Emelumadu, O.F. Prevalence of needle stick and sharps injury and hepatitis B vaccination among healthcare workers in a South-East Nigerian Tertiary Hospital. West Afr. J. Med. 2022, 39, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bioloogilistest Ohuteguritest Mõjutatud Töökeskkonna Töötervishoiu ja Tööohutuse Nõuded [Occupational Health and Safety Requirements for Workplaces Affected by Biological Agents]. Vabariigi Valitsus. Riigi Teataja. Available online: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/102042024015 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Council Directive 2010/32/EU of 10 May 2010 Implementing the Framework Agreement on Prevention from Sharp Injuries in the Hospital and Healthcare Sector Concluded by HOSPEEM and EPSU (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32010L0032 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Sharma, T.; Chaudhary, A.; Singh, J. Needle stick injuries and postexposure prophylaxis for hepatitis B infection. J. Appl. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2021, 2, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaranayake, L.; Scully, C. Needlestick and occupational exposure to infections: A compendium of current guidelines. Br. Dent. J. 2013, 215, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical Guidance for PEP. HIV Nexus: CDC Resources for Clinicians. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hivnexus/hcp/pep/index.html (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Kuhar, D.T.; Henderson, D.K.; Struble, K.A.; Heneine, W.; Thomas, V.; Cheever, L.W.; Gomaa, A.; Panlilio, A.L. Updated US Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to human immunodeficiency virus and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2013, 34, 875–892, Erratum in: Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2015, 34, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfulayw, K.H.; Al-Otaibi, S.T.; Alqahtani, H.A. Factors associated with needlestick injuries among healthcare workers: Implications for prevention. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swe, K.M.M.; Somrongthong, R.; Bhardwaj, A.; Abas, A. Needle sticks injury among medical students during clinical training, Malaysia. Int. J. Collab. Res. Intern. Med. Public Health 2014, 6, 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Rupak, K.C.; Khadka, D.; Ghimire, S.; Bist, A.; Patel, I.; Shahi, S.; Dhakal, N.; Tiwari, I.; Shrestha, D.B. Prevalence of exposure to needle stick and sharp-related injury and status of hepatitis B vaccination among healthcare workers: A cross-sectional study. Health Sci. Rep. 2023, 6, e1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joukar, F.; Mansour-Ghanaei, F.; Naghipour, M.; Asgharnezhad, M. Needlestick injuries among healthcare workers: Why they do not report their incidence? Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2018, 23, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghauri, A.J.; Amissah-Arthur, K.N.; Rashid, A.; Mushtaq, B.; Nessim, M.; Elsherbiny, S. Sharps injuries in ophthalmic practice. Eye 2011, 25, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Oweidat, I.; Al-Mugheed, K.; Alsenany, S.A.; Abdelaliem, S.M.F.; Alzoubi, M.M. Awareness of reporting practices and barriers to incident reporting among nurses. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praisie, R.; Anandadurai, D.; Nelson, S.B.; Venkateshvaran, S.; Thulasiram, M. Profile of splash, sharp and needle-stick injuries among healthcare workers in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Southern India. Cureus 2023, 15, e42671. [Google Scholar]

- Bahat, H.; Hasidov-Gafni, A.; Youngster, I.; Goldman, M.; Levtzion-Korach, O. The prevalence and underreporting of needlestick injuries among hospital workers: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2021, 33, mzab009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, S. Study of needle stick injuries among healthcare providers: Evidence from a teaching hospital in India. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardesai, R.V.; Gaurkar, S.P.; Sardesai, V.R.; Sardesai, V.V. Awareness of needle-stick injuries among health-care workers in a tertiary health-care center. Indian J. Sex. Transm. Dis. AIDS 2018, 39, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estonian Nurses Union. Õendus Arvudes [Nursing in Figures]. 2023. Available online: https://www.ena.ee/oendus-arvudes/ (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Tervisestatistika ja Terviseuuringute Andmebaas [Health Statistics and Health Research Database]. Available online: https://statistika.tai.ee/pxweb/et/Andmebaas/Andmebaas__04THressursid__05Tootajad/THT004.px/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Tööinspektsioon [Labor Inspectorate]. Available online: https://www.ti.ee/asutus-uudised-ja-kontaktid/kontakt/statistika (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Schuurmans, J.; Lutgens, S.P.; Groen, L.; Schneeberger, P.M. Do safety engineered devices reduce needlestick injuries? J. Hosp. Infect. 2018, 100, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, S.; Kayal, M.; Alahmad Almshhad, H.; Dirar, Q.; AlKattan, W.; Shibl, A.; Ouban, A. The incidence of needlestick and sharps injuries among healthcare workers in a Tertiary Care Hospital: A cross-sectional study. Cureus 2023, 15, e38097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.; Sartelli, M.; McKimm, J.; Abu Bakar, M. Health care-associated infections—An overview. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018, 11, 2321–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, C.E.; Stephens, J.M. Clinical, economic, and humanistic burden of needlestick injuries in healthcare workers. Med. Devices 2017, 10, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, C.; Sakisaka, K.; Sychareun, V.; Phensavanh, A.; Ali, M. Anxiety and perceived psychological impact associated with needle stick and sharp device injury among tertiary hospital workers, Vientiane, Lao PDR. Ind. Health 2020, 58, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | All Nurses | Safe NSIs | Real NSIs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = (%) | 211 | 155 (73.5) | 109 (51.7) | |

| Gender: female (%) | 97.63 | 97.42 | 97.25 | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 44.81 ± 12.32 | 44.63 ± 12.6 | 43.88 ± 12.17 | |

| Immunological status: hepatitis B (%) | I have had this disease | 1.90 | 1.94 | 1.83 |

| I am not vaccinated | 6.16 | 7.1 | 6.4 | |

| Vaccinated <5 y ago | 15.64 | 14.84 | 19.27 | |

| Vaccinated 5–10 y ago | 12.8 | 11.61 | 11.93 | |

| Vaccinated >10 y ago | 27.49 | 26.45 | 23.85 | |

| Antibodies have not been checked | 6.16 | 7.74 | 8.26 | |

| Antibodies have been checked within 5 y | 17.54 | 16.77 | 18.35 | |

| Antibody levels are up to the mark | 9.0 | 9.68 | 5.5 | |

| Few antibodies—I plan to vaccinate | 3.79 | 3.87 | 3.66 | |

| Few antibodies—do not plan to vaccinate | 0.95 | 1.29 | 1.83 | |

| Immunological status: hepatitis C (%) | I have had this disease | 0.95 | 1.29 | 0.92 |

| I do not know if I have had this disease | 29.38 | 32.26 | 33.03 | |

| I have been trained in NSI | 45.97 | 44.52 | 44.95 | |

| The number of needlesticks in the last ten years (%) | Once | 41.71 | 33.55 | 33.03 |

| Twice | 36.49 | 33.55 | 22.94 | |

| More than twice | 42.65 | 32.26 | 36.7 | |

| Occupational ward, where the needlestick injury occurred (%) | Pediatrics | 3.32 | 4.52 | 0 |

| Emergency department | 17.54 | 14.84 | 12.84 | |

| Internal medicine | 29.38 | 24.52 | 22.02 | |

| Obstetrics | 2.37 | 2.58 | 0.91 | |

| Surgery | 14.69 | 11.61 | 11.93 | |

| Operation room | 5.21 | 4.52 | 3.67 | |

| Intensive care unit | 9.95 | 8.39 | 7.34 | |

| Family doctor/nurse center | 21.33 | 18.71 | 14.68 | |

| NSI time (%) | Morning/day | 66.45 | 67.98 | |

| Evening | 27.74 | 30.28 | ||

| Night | 12.9 | 15.59 | ||

| Using gloves during a needlestick procedure | 80.65 | 88.07 | ||

| Type of needle (%) | Syringe needle (nature needle) | 56.87 | 74.84 | 71.56 |

| Suture needle | 3.79 | 5.16 | 6.42 | |

| Winged butterfly (winged steel needle) | 6.63 | 8.39 | 11.01 | |

| IV catheter stylet | 13.27 | 17.42 | 22.02 | |

| Needles with safety-engineered devices | 2.84 | 3.23 | 5.5 | |

| Other | 8.53 | 11.61 | 13.76 | |

| Action associated with injury (%) | Upon preparation | 26.54 | 36.13 | 18.35 |

| During taking blood | 10.43 | 14.19 | 17.43 | |

| During injection | 9.0 | 10.97 | 14.68 | |

| Upon pulling out | 9.48 | 11.61 | 16.51 | |

| When suturing a wound | 2.37 | 3.23 | 4.59 | |

| During sharps’ disposal | 17.54 | 23.23 | 33.03 | |

| Patient’s sudden movement | 14.22 | 18.71 | 23.77 | |

| Accidental prick from others | 0.95 | 0.65 | 1.83 | |

| Did not know that I need to inform | 14.71 |

| Did not know who to inform | 8.82 |

| I was too busy, I forgot | 17.65 |

| I was afraid of the negative impact on my work | 8.82 |

| I was afraid of losing my job | 2.94 |

| It’s not that important | 20.59 |

| After reporting, nothing is done | 20.59 |

| I had the laboratory done myself—was negative | 2.94 |

| Other | 20.59 |

| Didn’t want to comment | 17.65 |

| Opinions | Hepatitis B | Hepatitis C | HIV |

|---|---|---|---|

| The disease can be prevented by vaccination. | 96.27 | 25.37 | 4.48 |

| Lack of treatment | 8.21 | 12.69 | 9.70 |

| Treatment does not allow the pathogen to be completely defeated. | 38.06 | 48.51 | 76.12 |

| The treatment is effective and the person recovers completely. | 17.91 | 30.60 | 2.99 |

| Preventive treatment prevents the development of the disease if it is started as soon as possible. | 39.55 | ND | 58.96 |

| After an NSI, there is no preventive treatment for this disease. | 17.91 | 24.63 | 11.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parm, Ü.; Põiklik, T.; Tamm, A.-L. Understanding Needlestick Injuries Among Estonian Nurses: Prevalence, Contributing Conditions, and Safety Awareness. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050169

Parm Ü, Põiklik T, Tamm A-L. Understanding Needlestick Injuries Among Estonian Nurses: Prevalence, Contributing Conditions, and Safety Awareness. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(5):169. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050169

Chicago/Turabian StyleParm, Ülle, Triinu Põiklik, and Anna-Liisa Tamm. 2025. "Understanding Needlestick Injuries Among Estonian Nurses: Prevalence, Contributing Conditions, and Safety Awareness" Nursing Reports 15, no. 5: 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050169

APA StyleParm, Ü., Põiklik, T., & Tamm, A.-L. (2025). Understanding Needlestick Injuries Among Estonian Nurses: Prevalence, Contributing Conditions, and Safety Awareness. Nursing Reports, 15(5), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050169