Design and Validation of an Instrument to Measure the Communication of Bad News for Nurses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire Design and Development

2.2. Validation Study Design and Subject Selection

2.3. Sources of Information

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Validation of the Questionnaire

3.1.1. Content Validity

3.1.2. Construct Validity

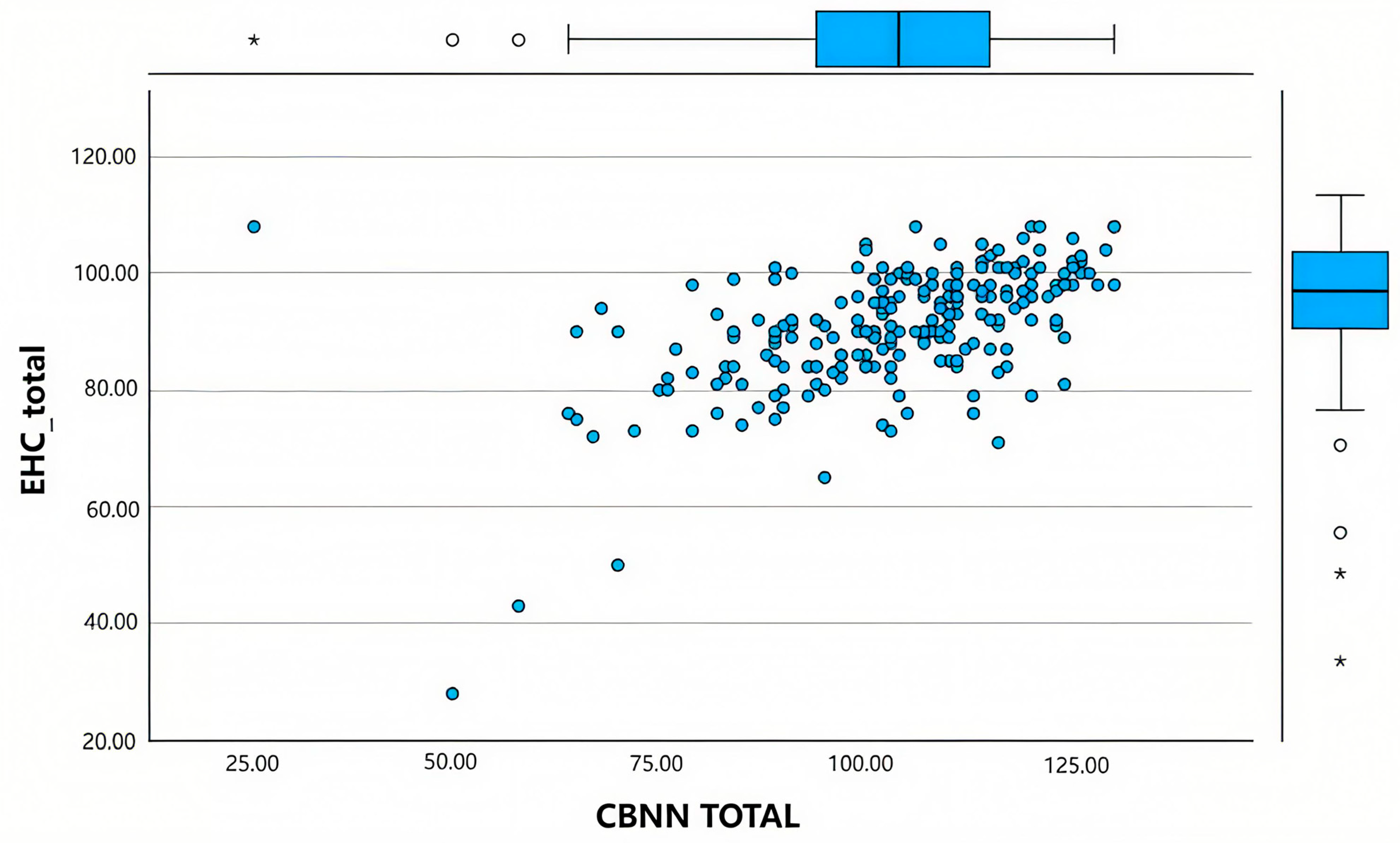

3.1.3. Convergent Validity

3.1.4. Criterion Validity

3.2. Internal Consistency

3.3. Temporary Stability

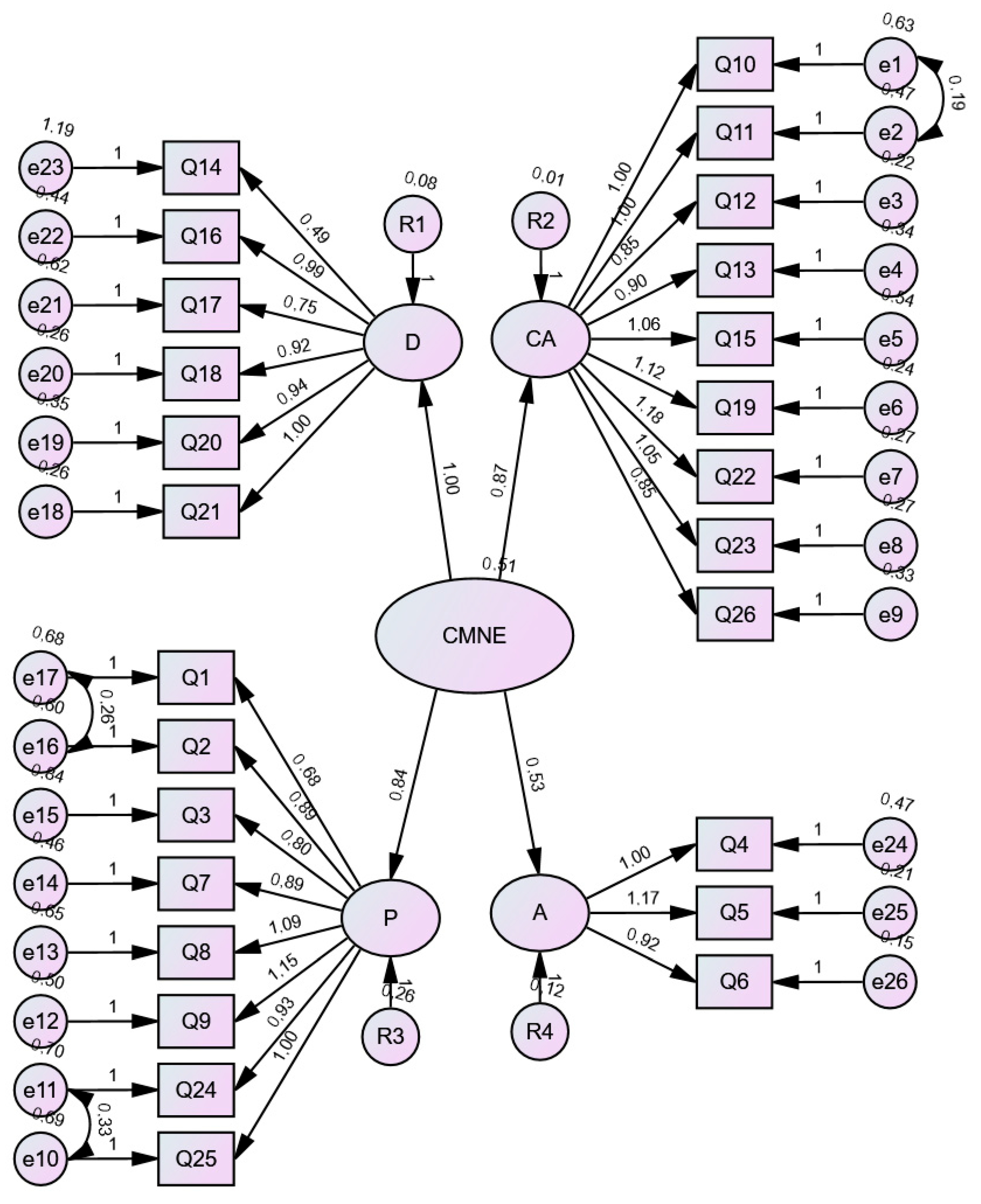

3.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- García Marco, M.I.; López Ibort, M.N.; Edo, V.; José, M. Reflexiones en torno a la Relación Terapéutica: ¿Falta de tiempo? Index Enfermería 2004, 13, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z. Delivering bad news to patients—The necessary evil. J. Med. Coll. PLA 2011, 26, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaszadeh, A.; Ehsani, S.R.; Begjani, J.; Kaji, M.A.; Dopolani, F.N.; Nejati, A.; Mohammadnejad, E. Nurses’ perspectives on breaking bad news to patients and their families: A qualitative content analysis. J. Med. Ethics Hist. Med. 2014, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aein, F.; Delaram, M. Giving bad news: A qualitative research exploration. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2014, 16, e8197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbabi, M.; Roozdar, A.; Taher, M.; Shirzad, S.; Arjmand, M.; Mohammadi, M.R.; Nejatisafa, A.A.; Tahmasebi, M.; Roozdar, A. How to break bad news: Physicians’ and nurses’ attitudes. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2010, 5, 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Saiote, E.; Mendes, F. A partilha de informação com familiares em unidade de tratamento intensivo: Importância atribuída por enfermeiros. Cogitare Enferm. 2011, 16, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, J.; Bolick, B.N. Preparing prelicensure and graduate nursing students to systematically communicate bad news to patients and families. J. Nurs. Educ. 2014, 53, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnock, C. Breaking bad news: Issues relating to nursing practice. Nurs. Stand. 2014, 28, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baile, W.F. Giving Bad News. Oncologist 2015, 20, 852–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achury Saldaña, D.M.; Pinilla Alarcón, M.; Alvarado Romero, H. Aspects that facilitate or interfere in the communication process between nursing professionals and patients in critical state. Investig. Educ. Enfermería 2015, 33, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirón González, R. Breaking bad news: Nursing perspective. Rev. Española Salud Pública. Available online: https://e-revistas.uc3m.es/index.php/RECS/article/download/3425/2076/ (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Park, I.; Gupta, A.; Mandani, K.; Haubner, L.; Peckler, B. Breaking bad news education for emergency medicine residents: A novel training module using simulation with the SPIKES protocol. J. Emergencies Trauma Shock 2010, 3, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, V.; Bista, B.; Koshy, C. “BREAKS” Protocol for Breaking Bad News. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2010, 16, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee on Improving the Quality of Cancer Care: Addressing the Challenges of an Aging Population; Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK202146/ (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Rabow, M.W.; McPhee, S.J. Beyond breaking bad news: How to help patients who suffer. West J. Med. 1999, 171, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koch, C.L.; Rosa, A.B.; Bedin, S.C. Bad news: Meanings attributed in neonatal/pediatric care practices. Rev. Bioética 2017, 25, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.; Dunn, S.; Heinrich, P. Managing the delivery of bad news: An in-depth analysis of doctors’ delivery style. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 87, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.A. Communication skills training of undergraduates. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2013, 23, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- De Vet, H.C.W.; Adèr, H.J.; Terwee, C.B.; Pouwer, F. Are factor analytical techniques used appropriately in the validation of health status questionnaires? A systematic review on the quality of factor analysis of the SF-36. Qual. Life Res. 2005, 14, 1203–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, P. An Easy Guide to Factor Analysis; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roco Videla, Á.; Hernández Orellana, M.; Silva González, O.; Roco Videla, Á.; Hernández Orellana, M.; Silva González, O. ¿Cuál es el tamaño muestral adecuado para validar un cuestionario? Nutr. Hosp. 2021, 38, 877–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.L. Instrument review: Getting the most from a panel of experts. Appl. Nurs. Res. 1992, 5, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almanasreh, E.; Moles, R.; Chen, T.F. Evaluation of methods used for estimating content validity. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2019, 15, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.; Fidell, L.; Ullman, J. Using Multivariate Statistics. 2013. Available online: https://www.pearsonhighered.com/assets/preface/0/1/3/4/0134790545.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, H.C.; Campo-Arias, A. Aproximación al uso del coeficiente alfa de Cronbach. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2005, 34, 572–580. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Moral, R.; De Pérula Torres, L.A. Validez y fiabilidad de un instrumento para evaluar la comunicación clínica en las consultas: El cuestionario CICAA. Atención Primaria 2006, 37, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Cabrera, M.; Ortega-Martínez, A.R.; Martínez-Galiano, J.M.; Hernández-Martínez, A.; Parra-Anguita, L.; Frías-Osuna, A. Design and Validation of a Questionnaire on Communicating Bad News in Nursing: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawshe, C.H. A Quantitative Approach to Content Validity. Pers. Psychol. 2006, 28, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egaña, M.U.; Barrios, S.; Núñez, M.G.; Camus, M.M. Métodos óptimos para determinar validez de contenido. Rev. Cuba. Educ. Médica Super. 2014, 28, 547–558. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=s0864-21412014000300014&script=sci_arttext (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Astudillo Araya, Á.A.; López Espinoza, M.Á.; López Espinoza, M.Á.; León Pino, J.M.; Grupo de investigación en simulación clínica GISC. Propiedades psicométricas de la escala CICAA (Conectar, Identificar, Comprender, Acordar y Ayudar) utilizada en simulación clínica de alta fidelidad de estudiantes de Enfermería. Index Enfermería 2023, 32, e14375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro Romero, K.; Martínez Mora, O. Análisis factorial exploratorio mediante el uso de las medidas de adecuación muestral kmo y esfericidad de bartlett para determinar factores principales. J. Sci. Res. 2020, 5, 903–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Costa, C.; Tirado-González, S.; van-der Hofstadt Román, C.J.; Rodríguez-Marín, J. Creación de la Escala sobre Habilidades de comunicación en Profesionales de la Salud, EHC-PS. An. Psicol. 2016, 32, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourth, S.; Zambrano, C.; Ceballos, A.K.; Benavides, V.; Villota, N. Habilidades sociales relacionadas con el proceso de comunicación en una muestra de adolescentes. Psicoespacios Rev. Virtual La Inst. Univ. Envigado 2017, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Leal-Costa, C.; Tirado González, S.; Ramos-Morcillo, A.; Díaz Agea, J.; Ruzafa-Martínez, M.; Hofstadt Román, C.; van-der Leal-Costa, C.; Tirado González, S.; Ramos-Morcillo, A.; Díaz Agea, J.; et al. Validación de la Escala sobre Habilidades de Comunicación en profesionales de Enfermería. An. Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2019, 42, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streiner, D.; Norman, G.; Cairney, J. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=pb30EAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Streiner+D,+Norman+G,+Cairney+J.+Health+Measurement+Scales:+A+Practical+Devel-opment+and+Usetle.+5th+ed.+Oxford:+Oxford+University+Pres%3B+2015.+&ots=TOLKul9AIM&sig=9cevyly9N8Z104w1KjSKjL0OFYo (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Miller, S.J.; Hope, T.; Talbot, D.C. The development of a structured rating schedule (the BAS) to assess skills in breaking bad news. Br. J. Cancer 1999, 80, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prat, G.; Casas-Anguera, E.; Garcia-Franco, M.; Escandell, M.J.; Martin, J.R.; Vilamala, S.; Villalta-Gil, V.; Gimenez-Salinas, J.; Hernández-Rambla, C.; Ochoa, S. Validation of the Communication Skills Questionnaire (CSQ) in people with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 220, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, M.; Tanaka, K.; Miyaoka, H. Reliability and validity of communication skills questionnaire (CSQ). Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 60, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista-Foguet, J.M.; Coenders, G.; Alonso, J. Análisis factorial confirmatorio. Su utilidad en la validación de cuestionarios relacionados con la salud. Med. Clínica 2004, 122, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Mean CBNN score (SD) | 103.13 (16.6) |

| Biological sex | |

| Male | 51 (23.4) |

| Female | 167 (76.6) |

| Current workplace | |

| Public sector | 181 (83.0) |

| Private sector | 14 (6.4) |

| Both (public and private sectors) | 15 (6.9) |

| Not currently working | 8 (3.7) |

| Current position | |

| Emergency | 40 (18.3) |

| Intensive Critical Unit | 16 (7.3) |

| Hospital care | 45 (20.6) |

| Family nurse | 33 (15.1) |

| Outpatients | 10 (4.6) |

| Operating theatre | 10 (4.6) |

| Palliative care | 4 (1.8) |

| Socio-health Centre | 11 (5.0) |

| Unemployed | 7 (3.2) |

| Another | 42 (19.3) |

| Work shift | |

| Rotational shift work | 112 (51.4) |

| Daytime | 71 (32.6) |

| On-call | 32 (14.7) |

| Nights | 3 (1.4) |

| Type of contract (current) | |

| Statutory | 83 (38.1) |

| Interim | 37 (17.0) |

| Eventual | 75 (34.4) |

| Another | 23 (10.6) |

| Professional experience | |

| <1 year | 18 (8.3) |

| 1–5 years | 50 (22.9) |

| 5–10 years | 61 (28.0) |

| >10 years | 89 (40.8) |

| Education profile | |

| Diploma/Graduate | 115 (52.8) |

| Expert | 9 (4.1) |

| Master’s degree | 61 (28.0) |

| Specialization | 26 (11.9) |

| PhD | 7 (3.2) |

| Previous undergraduate training | |

| Have you received CBN training? | |

| Yes | 113 (51.8) |

| No | 105 (48.2) |

| Postgraduate training | |

| Have you received CBN training? | |

| Yes | 65 (29.8) |

| No | 153 (70.2) |

| Do you see a need for CBN training? | |

| Yes | 217 (99.5) |

| No | 1 (0.5) |

| Do you consider that CBN is part of nursing work? | |

| Yes | 204 (93.6) |

| No | 14 (6.4) |

| Level of preparedness for CBN | |

| None | 13 (6.0) |

| Little | 53 (24.3) |

| Some | 111 (50.9) |

| Quite well prepared | 38 (17.4) |

| Very prepared | 3 (1.4) |

| Level of concern for CBN | |

| No concern | 1 (0.5) |

| A little concern | 4 (1.8) |

| Some concern | 26 (11.9) |

| Quite concerned | 122 (56.0) |

| Very concerned | 65 (29.8) |

| Have you ever reported bad news? | |

| Yes | 161 (73.9) |

| No | 57 (26.1) |

| If you have made the communication of bad news, Do you ever specify in which service? n (%) | |

| Hospital emergency care | 25 (11.5) |

| Out-of-hospital emergencies | 11 (5.0) |

| Intensive Critical Unit | 16 (7.3) |

| Palliative care | 11 (5.0) |

| Hospital care | 38 (17.4) |

| Primary care | 14 (6.4) |

| Mental health | 2 (0.9) |

| Socio-health Centre | 3 (1.4) |

| Old people’s home | 12 (5.5) |

| Delivery unit | 5 (2.3) |

| Oncology | 7 (3.2) |

| Emergency Call Center | 2 (0.9) |

| Ambiguous | 3 (1.4) |

| Pediatrics | 1 (0.5) |

| Item | Never N (%) | Hardly Ever N (%) | Sometimes N (%) | Most of the Time N (%) | Always N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBNN1 | 5 (2.3) | 12 (5.5) | 48 (22.0) | 82 (37.6) | 71 (32.6) |

| CBNN2 | 10 (4.6) | 19 (8.7) | 55 (25.2) | 89 (40.8) | 45 (20.6) |

| CBNN3 | 35 (16.1) | 71 (32.6) | 63 (28.9) | 36 (16.5) | 13 (6.0) |

| CBNN4 | 2 (0.9) | 7 (3.2) | 20 (9.2) | 43 (19.7) | 146 (67.0) |

| CBNN5 | 2 (0.9) | 4 (1.8) | 13 (6.0) | 40 (18.3) | 159 (72.9) |

| CBNN6 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 8 (3.7) | 47 (21.6) | 161 (73.9) |

| CBNN7 | 123 (56.4) | 61 (28.0) | 19 (8.7) | 13 (6.0) | 2 (0.9) |

| CBNN8 | 3 (1.4) | 14 (6.4) | 48 (22.0) | 75 (34.4) | 78 (35.8) |

| CBNN9 | 16 (7.3) | 35 (16.1) | 63 (28.9) | 60 (27.5) | 44 (20.2) |

| CBNN10 | 10 (4.6) | 43 (19.7) | 58 (26.6) | 62 (28.4) | 45 (20.6) |

| CBNN11 | 4 (1.89) | 17 (7.8) | 39 (17.9) | 77 (35.3) | 81 (37.2) |

| CBNN12 | 3 (1.4) | 7 (3.2) | 33 (15.1) | 57 (26.1) | 118 (54.1) |

| CBNN13 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 20 (9.2) | 41 (18.8) | 155 (71.1) |

| CBNN14 | 2 (0.9) | 3 (1.4) | 25 (11.5) | 72 (33.0) | 116 (53.2) |

| CBNN15 | 21 (9.6) | 48 (22.0) | 65 (29.8) | 59 (27.1) | 25 (11.5) |

| CBNN16 | 39(17.9) | 66 (30.3) | 77 (35.3) | 27 (12.4) | 9 (4.1) |

| CBNN17 | 5 (2.3) | 24 (11.0) | 64 (29.4) | 82 (37.6) | 43 (19.7) |

| CBNN18 | 4 (1.8) | 20 (9.2) | 45 (20.6) | 83 (38.1) | 66 (30.3) |

| CBNN19 | 5 (2.3) | 17 (7.8) | 54 (24.8) | 89 (40.8) | 53 (24.3) |

| CBNN20 | 3 (1.4) | 5 (2.3) | 26 (11.9) | 73 (33.5) | 111 (50.9) |

| CBNN21 | 2 (0.9) | 7 (3.2) | 23 (10.6) | 70 (32.1) | 116 (53.2) |

| CBNN22 | 3 (1.4) | 12 (5.5) | 41 (18.8) | 89 (40.8) | 73 33.5) |

| CBNN23 | 4 (1.8) | 10 (4.6) | 51 (18.8) | 92 (42.2) | 61 (28.0) |

| CBNN24 | 3 (1.4) | 8 (3.7) | 29 (13.3) | 78 (35.8) | 100 (45.9) |

| CBNN25 | 2 (0.9) | 6 (2.8) | 26 (11.9) | 84 (38.5) | 100 (45.9) |

| CBNN26 | 7 (3.2) | 35 (16.1) | 47 (21.6) | 75 (34.4) | 54 (24.8) |

| CBNN27 | 9 (4.1) | 30 (13.8) | 64 (29.4) | 55 (25.2) | 60 (27.5) |

| CBNN28 | 4 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (8.3) | 24 (11.0) | 172 (78.9) |

| Elements | Editorial Staff | Comprehension | Relevance | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |

| Item 1 | 1.5 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) |

| Item 2 | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) |

| Item 3 | 2.0 (2) | 2.0 (2) | 2.0 (3) | 2.0 (2) |

| Item 4 | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) |

| Item 5 | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) |

| Item 6 | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) |

| Item 7 | 2.0 (2) | 1.5 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 1.5 (2) |

| Item 8 | 2.0 (2) | 2.0 (2) | 1.0 (1) | 2.0 (2) |

| Item 9 | 3.0 (1) | 3.0 (1) | 1.5 (1) | 2.0 (2) |

| Item 10 | 2.5 (2) | 2.0 (2) | 2.0 (3) | 2.5 (2) |

| Item 11 | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 2.5 (3) | 1.5 (3) |

| Item 12 | 2.0 (3) | 1.5 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 2.0 (2) |

| Item 13 | 2.0 (3) | 1.5 (2) | 2.0 (2) | 1.5 (2) |

| Item 14 | 1.5 (2) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) |

| Item 15 | 2.5 (2) | 2.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 1.5 (1) |

| Item 16 | 2.0 (2) | 1.5 (1) | 2.0 (2) | 1.5 (2) |

| Item 17 | 1.5 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 1.5 (3) | 1.0 (1) |

| Item 18 | 2.0 (2) | 2.0 (1) | 1.5 (2) | 2.0 (1) |

| Item 19 | 1.5 (2) | 1.5 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 1.5 (1) |

| Item 20 | 1.5 (2) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) |

| Item 21 | 2.0 (1) | 1.5 (2) | 1.5 (2) | 1.5 (1) |

| Item 22 | 2.0 (1) | 2.0 (0) | 2.0 (1) | 2.0 (1) |

| Item 23 | 1.5 (1) | 2.0 (2) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) |

| Item 24 | 2.0 (2) | 3.0 (1) | 2.0 (2) | 2.0 (2) |

| Item 25 | 2.5 (3) | 2.5 (3) | 2.0 (2) | 2.5 (2) |

| Item 26 | 1.5 (1) | 1.5 (2) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) |

| Item 27 | 2.0 (1) | 2.0 (2) | 1.0 (1) | 1.5 (1) |

| Item 28 | 1.0 (1) | 2.0 (2) | 1.0 (2) | 1.5 (2) |

| Item 29 | 1.5 (2) | 1.5 (1) | 1.5 (1) | 1.5 (1) |

| Item 30 | 2.0 (3) | 2.0 (2) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) |

| Item 31 | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) |

| 28 ITEMS | AFTER REMOVING 7 & 16 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IMCBNN 1 | 0.911 | IMCBNN 1 | 0.914 |

| IMCBNN 2 | 0.900 | IMCBNN 2 | 0.908 |

| IMCBNN 3 | 0914 | IMCBNN 3 | 0.913 |

| IMCBNN 4 | 0.941 | IMCBNN 4 | 0.941 |

| IMCBNN 5 | 0.897 | IMCBNN 5 | 0.895 |

| IMCBNN 6 | 0.927 | IMCBNN 6 | 0.928 |

| IMCBNN 7 | 0.494 | IMCBNN 8 | 0.920 |

| IMCBNN 8 | 0.911 | IMCBNN 9 | 0.949 |

| IMCBNN 9 | 0.948 | IMCBNN 10 | 0.907 |

| IMCBNN 10 | 0.895 | IMCBNN 11 | 0.943 |

| IMCBNN 11 | 0.945 | IMCBNN 12 | 0.948 |

| IMCBNN 12 | 0.946 | IMCBNN 13 | 0.940 |

| IMCBNN 13 | 0.936 | IMCBNN 14 | 0.928 |

| IMCBNN 14 | 0.930 | IMCBNN 15 | 0.818 |

| IMCBNN 15 | 0.811 | IMCBNN 17 | 0.931 |

| IMCBNN 16 | 0.562 | IMCBNN 18 | 0.926 |

| IMCBNN 17 | 0.929 | IMCBNN 19 | 0.928 |

| IMCBNN 18 | 0.925 | IMCBNN 20 | 0.925 |

| IMCBNN 19 | 0.933 | IMCBNN 21 | 0.937 |

| IMCBNN 20 | 0.924 | IMCBNN 22 | 0.952 |

| IMCBNN 21 | 0.938 | IMCBNN 23 | 0.960 |

| IMCBNN 22 | 0.951 | IMCBNN 24 | 0.972 |

| IMCBNN 23 | 0.959 | IMCBNN 25 | 0.954 |

| IMCBNN 24 | 0.969 | IMCBNN 26 | 0.894 |

| IMCBNN 25 | 0.956 | IMCBNN 27 | 0.905 |

| IMCBNN 26 | 0.889 | IMCBNN 28 | 0.945 |

| IMCBNN 27 | 0.894 | ||

| IMCBNN 28 | 0.940 | ||

| Components | Initial Values | Rotational Sums of Extracted Squared | Rotational Sums of Squared Loads | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % De Variance | % Accumulated | Total | % De Variance | % Accumulated | Total | % De Variance | % Accumulated | |

| 1 | 11.499 | 44.227 | 44.227 | 11.499 | 44.227 | 44.227 | 5.171 | 19.890 | 19.890 |

| 2 | 1.937 | 7.450 | 51.677 | 1.937 | 7.450 | 51.627 | 4.457 | 17.142 | 37.032 |

| 3 | 1.624 | 6.244 | 57.922 | 1.624 | 6.244 | 57.922 | 3.703 | 14.242 | 51.274 |

| 4 | 1.049 | 4.037 | 61.958 | 1.049 | 4.037 | 61.958 | 2.778 | 10.684 | 63.958 |

| 5 | 1.020 | 3.925 | 65.883 | ||||||

| 6 | 0.847 | 3.259 | 69.142 | ||||||

| 7 | 0.803 | 3.089 | 72.231 | ||||||

| 8 | 0.692 | 2.660 | 74.891 | ||||||

| 9 | 0.632 | 2.429 | 77.321 | ||||||

| 10 | 0.570 | 2.191 | 79.511 | ||||||

| 11 | 0.528 | 2.032 | 81.543 | ||||||

| 12 | 0.500 | 1.923 | 83.466 | ||||||

| 13 | 0.481 | 1.850 | 85.316 | ||||||

| 14 | 0.473 | 1.818 | 87.134 | ||||||

| 15 | 0.392 | 1.509 | 88.643 | ||||||

| 16 | 0.385 | 1.479 | 90.122 | ||||||

| 17 | 0.342 | 1.316 | 91.438 | ||||||

| 18 | 0.335 | 1.290 | 92.728 | ||||||

| 19 | 0.321 | 1.235 | 93.963 | ||||||

| 20 | 0.288 | 1.106 | 95.070 | ||||||

| 21 | 0.278 | 1.068 | 96.138 | ||||||

| 22 | 0.249 | 0.957 | 97.095 | ||||||

| 23 | 0.232 | 0.893 | 97.988 | ||||||

| 24 | 0.203 | 0.781 | 98.768 | ||||||

| 25 | 0.180 | 0.692 | 99.460 | ||||||

| 26 | 0.140 | 0.540 | 100.000 | ||||||

| Components | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Empathy and Perception | Environment Preparation, Invitation and Strategy | Information Given and the Act of Communicate | Communication Method |

| CBNN1 | 0.499 | |||

| CBNN 2 | 0.677 | |||

| CBNN 3 | 0.713 | |||

| CBNN 4 | 0.684 | |||

| CBNN 5 | 0.749 | |||

| CBNN 6 | 0.703 | |||

| CBNN 8 | 0.556 | |||

| CBNN 9 | 0.709 | |||

| CBNN 10 | 0.747 | |||

| CBNN 11 | 0.496 | |||

| CBNN 12 | 0.649 | |||

| CBNN 13 | 0.654 | |||

| CBNN 14 | 0.731 | |||

| CBNN 15 | 0.523 | |||

| CBNN 17 | 0.497 | |||

| CBNN 18 | 0.606 | |||

| CBNN 19 | 0.758 | |||

| CBNN 20 | 0.600 | |||

| CBNN 21 | 0.608 | 0.583 | ||

| CBNN 22 | 0.566 | |||

| CBNN 23 | 0.535 | |||

| CBNN 24 | 0.599 | |||

| CBNN 25 | 0.628 | |||

| CBNN 26 | 0.552 | |||

| CBNN 27 | 0.624 | |||

| CBNN 28 | 0.552 | |||

| Variable | CBNN Scoring | p Value (Combined) |

|---|---|---|

| (SD) | ||

| CBNN | 103.13 (16.16) | |

| EHC | 90.81 (10.54) | |

| Age | 39.40 (12.19) | |

| Biological sex | 0.007 | |

| Male | 97.78 (14.74) | |

| Female | 104.76 (16.27) | |

| Current workplace | 0.989 | |

| Public | 103.06 (15.67) | |

| Private | 102.79 (15.59) | |

| Both | 104.53 (12.10) | |

| Not currently working | 102.75 (32.23) | |

| Current position | 0.277 | |

| Emergency | 98.07 (12.99) | |

| ICU | 104.87 (19.06 | |

| Hospital care | 100.51 (19.03) | |

| Family Nurse | 106.88 (11.81) | |

| Consultations | 107.10 (15.49) | |

| Operating theatre | 104.60 (10.99) | |

| Palliative care | 104.25 (23.64) | |

| Socio-health centre | 109.82 (12.03) | |

| Unemployed | 97.57 (34.02) | |

| Other | 104.90 (14.04) | |

| Type of shift pattern | 0.384 | |

| Rotational shift work | 102.35 (18.17) | |

| Daytime | 105.60 (14.30) | |

| 24 h shifts | 100.16 (12.32) | |

| Night | 105.33 (10.41) | |

| Type of contract (current) | 0.295 | |

| Statutory | 101.14 (17.15) | |

| Interim | 107.27 (13.84) | |

| Eventual | 103.41 (13.95) | |

| Another | 102.69 (21.63) | |

| Professional experience | 0.550 | |

| <1 year | 106.22 (23.51) | |

| 1–5 years | 104.74 (14.29) | |

| 5–10 years | 101.10 (13.07) | |

| >10 years | 102.98 (17.35) | |

| Educational profile | 0.776 | |

| Diploma/Graduate | 102.75 (18.14) | |

| Expert | 105.11 (17.29 | |

| Master’s degree | 102.64 (12.45) | |

| Specialization | 103.23 (15.99) | |

| PhD | 110.71 (10.13) | |

| Previous undergraduate training Have you received CBN training? | 0.470 | |

| Yes | 103.89 (16.10) | |

| No | 102.30 (16.27) | |

| Postgraduate training Have you received CBN training? | 0.211 | |

| Yes | 105.23 (15.86) | |

| No | 102.23 (16.26) | |

| Do you see a need for CBN training? | 0.001 | |

| Yes | 103.37 (15.79) | |

| No | 50.00 | |

| Do you consider that CBN is a part of nursing work? | 0.095 | |

| Yes | 103.61 (15.79) | |

| No | 96.14 (20.29) | |

| Degree of preparation for CBN | <0.001 | |

| None | 87.77 (25.81) | |

| Little | 100.90 (14.23) | |

| Some | 103.21 (14.98) | |

| OK | 111.16 (13.75) | |

| A lot | 104.33 (18.58) | |

| Degree of concern about CBN | 0.923 | |

| No concern | 109.00 | |

| A little concerned | 98.00 (11.04) | |

| Some concern | 105.04 (11.35) | |

| Quite concerned | 102.93 (17.01) | |

| Very concerned | 102.97 (16.71) | |

| Have you ever given bad news? | 0.573 | |

| Yes | 103.50 (15.38) | |

| No | 102.09 (18.31) |

| Reliability with All Items of the CBNN Questionnaire | Reliability When Items 7 and 16 of the CBNN Questionnaire Are Removed | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CBNN | Cronbach’Alpha (α) | CBNN | Cronbach’Alpha (α) |

| Total | 0.935 | Total | 0.944 |

| CBNN1 | 0.933 | CBNN 1 | 0.943 |

| CBNN 2 | 0.932 | CBNN 2 | 0.942 |

| CBNN 3 | 0.934 | CBNN 3 | 0.944 |

| CBNN 4 | 0.934 | CBNN 4 | 0.944 |

| CBNN 5 | 0.933 | CBNN 5 | 0.943 |

| CBNN 6 | 0.933 | CBNN 6 | 0.943 |

| CBNN 7 | 0.940 | CBNN 8 | 0.942 |

| CBNN 8 | 0.932 | CBNN 9 | 0.943 |

| CBNN 9 | 0.932 | CBNN 10 | 0.942 |

| CBNN 10 | 0.931 | CBNN 11 | 0.942 |

| CBNN 11 | 0.932 | CBNN 12 | 0.942 |

| CBNN 12 | 0.932 | CBNN 13 | 0.942 |

| CBNN 13 | 0.932 | CBNN 14 | 0.942 |

| CBNN 14 | 0.932 | CBNN 15 | 0.947 |

| CBNN 15 | 0.936 | CBNN 17 | 0.942 |

| CBNN16 | 0.939 | CBNN 18 | 0.941 |

| CBNN 17 | 0.931 | CBNN 19 | 0.944 |

| CBNN 18 | 0.931 | CBNN 20 | 0.941 |

| CBNN 19 | 0.933 | CBNN 21 | 0.941 |

| CBNN20 | 0.931 | CBNN 22 | 0.941 |

| CBNN 21 | 0.931 | CBNN 23 | 0.941 |

| CBNN 22 | 0.931 | CBNN 24 | 0.940 |

| CBNN 23 | 0.930 | CBNN 25 | 0.941 |

| CBNN24 | 0.930 | CBNN 26 | 0.942 |

| CBNN 25 | 0.931 | CBNN 27 | 0.942 |

| CBNN 26 | 0.931 | CBNN 28 | 0.943 |

| CBNN 27 | 0.932 | ||

| CBNN 28 | 0.932 | ||

| Indicators | Benchpoints | Estimated Values After Correlating Errors |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute adjustment indices | ||

| Chi-square | >0.005 | <0.001 |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | <0.08 | 0.079 |

| Incremental Adjustment Indices | ||

| Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) | >0.90 | 0.868 |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | >0.90 | 0.881 |

| Normed Fit Index (NFI) | >0.90 | 0.812 |

| Parsimonious Adjustment Indices | ||

| Parsimony Ratio (PRATIO) | >0.90 | 0.898 |

| Comparative Fixed Parsimony Index (PCFI) | >0.80 | 0.792 |

| Parsimony Normed fit Index (PNFI) | >0.80 | 0.729 |

| Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) | Minor value | 803.960 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Cabrera, M.; Martínez-Vázquez, S.; Hernández-Martínez, A.; Peinado-Molina, R.A.; Díaz-Ogallar, M.A.; Martínez-Galiano, J.M. Design and Validation of an Instrument to Measure the Communication of Bad News for Nurses. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050156

González-Cabrera M, Martínez-Vázquez S, Hernández-Martínez A, Peinado-Molina RA, Díaz-Ogallar MA, Martínez-Galiano JM. Design and Validation of an Instrument to Measure the Communication of Bad News for Nurses. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(5):156. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050156

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Cabrera, Manuel, Sergio Martínez-Vázquez, Antonio Hernández-Martínez, Rocío Adriana Peinado-Molina, María Antonia Díaz-Ogallar, and Juan Miguel Martínez-Galiano. 2025. "Design and Validation of an Instrument to Measure the Communication of Bad News for Nurses" Nursing Reports 15, no. 5: 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050156

APA StyleGonzález-Cabrera, M., Martínez-Vázquez, S., Hernández-Martínez, A., Peinado-Molina, R. A., Díaz-Ogallar, M. A., & Martínez-Galiano, J. M. (2025). Design and Validation of an Instrument to Measure the Communication of Bad News for Nurses. Nursing Reports, 15(5), 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050156