Between Clicks and Care: Investigating Social Media Addiction and Work Engagement Among Nurses in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting and Participants

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Collection Method

- Part I: Nurses’ Sociodemographic Data

- Part II: Assessment of Social Networking Addiction

- Part III: Work Engagement Scale

- Vigor (6 items): Measures energy levels, mental concentration, effort, and persistence in facing challenges.

- Dedication (5 items): Assesses a sense of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, and pride in work.

- Absorption (6 items): Evaluates full immersion in work, with a perception of time passing quickly and reduced distraction.

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

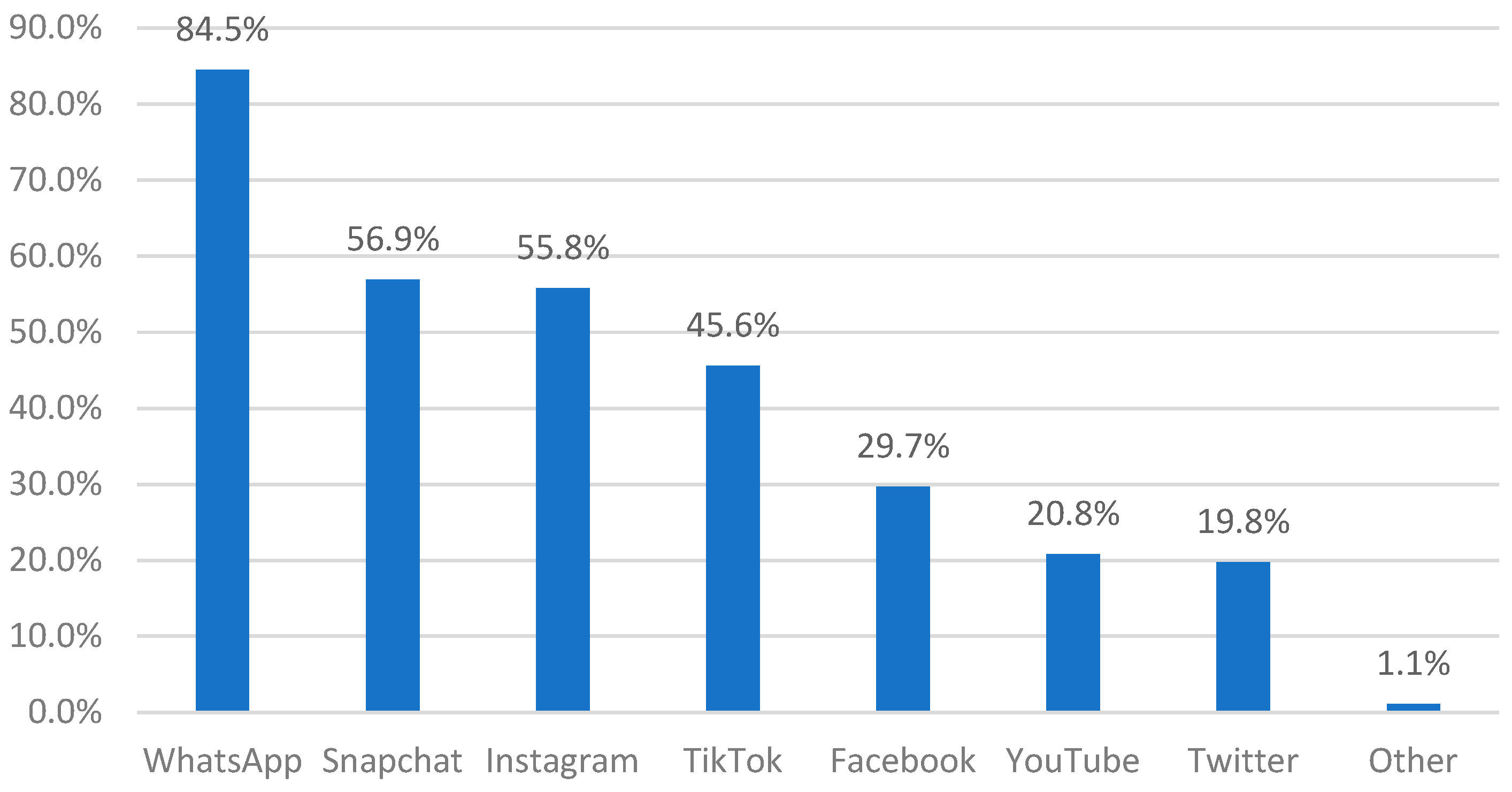

3.2. Assessment of Social Media Networking Addictions Among Nurses

3.3. Assessment of Nurses’ Work Engagement

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SMNA | Social Media Networking Addiction |

| SNAS | Social Media Networking Addiction Scale |

| WE | Work Engagement |

| UWES | Utrecht Work Engagement Scale |

References

- Firth, J.; Torous, J.; Stubbs, B.; Firth, J.A.; Steiner, G.Z.; Smith, L.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Gleeson, J.; Vancampfort, D.; Armitage, C.J.; et al. The “online brain”: How the Internet may be changing our cognition. World Psychiatry 2019, 18, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuss, D.; Griffiths, M. Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montag, C.; Demetrovics, Z.; Elhai, J.D.; Grant, D.; Koning, I.; Rumpf, H.J.; Spada, M.M.; Throuvala, M.; van den Eijnden, R. Problematic social media use in childhood and adolescence. Addict. Behav. 2024, 153, 107980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kheir, D.Y.M.; Boumarah, D.N.; Bukhamseen, F.M.; Masoudi, J.H.; Boubshait, L.A. The Saudi experience of health-related social media use: A scoping review. Saudi J. Health Syst. Res. 2021, 1, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ahdal, A.A.M.H.; Aljafen, B.S. Social media platforms: Perceptions and concerns of Saudi EFL learners. World J. Engl. Lang. 2023, 13, 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, C.; Tham, T.L.; Holland, P.; Cooper, B.K.; Newman, A. The relationship between HIWPs and nurse work engagement: The role of job crafting and supervisor support. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 34, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, K.; Jaiswal, A.; Kumar, T. Navigating the Digital Landscape: A Comprehensive Analysis of Social Media’s Impact on Mental Health. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Technol. 2024, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rath, M. Application and Impact of Social Network in Modern Society. In Hidden Link Prediction in Stochastic Social Networks; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 30–49. [Google Scholar]

- Shahnawaz, M.G.; Rehman, U. Social Networking Addiction Scale. Cogent Psychol. 2020, 7, 1832032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al, U.B.A. Social Networking Sites (SNSs) Addiction. J. Fam. Med. Dis. Prev. 2018, 4, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, E.; Kuss, D.J. Depression among users of social networking sites (SNSs): The role of SNS addiction and increased usage. J. Addict. Prev. Med. 2016, 1, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Online social networking and addiction—A review of the psychological literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 3528–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatta, M.; Ravish, G. Impact of Social Media on the Professional Development of Health Professionals. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Computing, Power and Communication Technologies (IC2PCT), Greater Noida, India, 9–10 February 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; Volume 5, pp. 1778–1781. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, A.; Yasir, M.; Majid, A.; Shah, H.A.; Islam, E.U.; Asad, S.; Khan, M.W. Evaluating the effects of social networking sites addiction, task distraction, and self-management on nurses’ performance. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 2820–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeyaraman, M.; Ramasubramanian, S.; Kumar, S.; Jeyaraman, N.; Selvaraj, P.; Nallakumarasamy, A.; Bondili, S.K.; Yadav, S. Multifaceted role of social media in Healthcare: Opportunities, challenges, and the need for Quality Control. Cureus 2023, 15, e39111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healthcare Transformation Strategy. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/vro/Documents/Healthcare-Transformation-Strategy.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Alghamdi, S.; El-Sayed, A.; Anwar, M. Social media usage among healthcare professionals in Saudi Arabia: A study of behavioral patterns and impacts. Saudi J. Health 2022, 45, 212–220. [Google Scholar]

- Alfifi, H.J.; Mahran, S.; Alabdulah, N. Levels and factors influencing work engagement among nurses in Najran hospitals. IOSR J. Nurs. Health Sci. 2020, 8, 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Alkorashy, H.; Alanazi, M. Personal and job-related factors influencing the work engagement of hospital nurses: A cross-sectional study from Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2023, 11, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoşgör, H.; Dörttepe, Z.U.; Memiş, K. Social media addiction and work engagement among nurses. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 57, 1966–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, N.A.; Farghaly Abd-El Aliem, S.M.; Alsayed, S.K. The relationship between nurses’ job crafting behaviours and their work engagement. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboshaiqah, A.E.; Hamadi, H.Y.; Salem, O.A.; Zakari, N.M. The work engagement of nurses in multiple hospital sectors in Saudi Arabia: A comparative study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Social media addiction and its impact on emotional exhaustion and work engagement among nurses. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2023, 62, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ariani, D.W.; Sulistyawati, H. Social media addiction and its impact on job performance among nurses. Nurs. Pract. 2020, 15, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, M. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J. Subst. Use Addict. Treat. 2005, 10, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A. Wilmar Schaufeli. Available online: https://www.wilmarschaufeli.nl/tests/ (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Computer software. IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019.

- Malapane, T.A.; Ndlovu, N.K. Assessing the Reliability of Likert Scale Statements in an E-Commerce Quantitative Study: A Cronbach Alpha Analysis Using SPSS Statistics. In Proceedings of the 2024 Systems and Information Engineering Design Symposium (SIEDS), Charlottesville, VA, USA, 3 May 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Hou, L.; Zhou, W.; Shen, L.; Jin, S.; Wang, M.; Shang, S.; Cong, X.; Jin, X.; Dou, D. Trends, composition and distribution of nurse workforce in China: A secondary analysis of national data from 2003 to 2018. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e047348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, J.D.F. O Enfermeiro no Exercício de Uma Profissão Predominantemente Feminina: Uma Revisão Integrativa. Monografia (Graduação) Curso de Enfermagem. Diploma Thesis, Universidade Federal do Maranhão, São Luiz, MA, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alboliteeh, M.; Magarey, J.; Wiechula, R. The profile of Saudi nursing workforce: A cross-sectional study. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2017, 2017, 1710686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salihu, K. The Evolution of Nursing as A Profession in Healthcare. MEDIS–Int. J. Med. Sci. Res. 2024, 3, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouin, R.; Potter, M. Flexible Scheduling: Exploring the benefits and the limitations. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 2005, 105, 72E–72F. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Friese, C.R.; Siefert, M.L.; Thomas-Frost, K.; Walker, S.; Ponte, P.R. Using data to strengthen ambulatory oncology nursing practice. Cancer Nurs. 2016, 39, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwoke, L.I. Social Media Use and Emotional Regulation in Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Longitudinal Examination of Moderating Factors. Int. J. Med. Sci. Clin. Invent. 2017, 4, 2816–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfers, L.N.; Utz, S. Social media use, stress, and coping. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 45, 101305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, A.; Kong, W.; He, H.; Li, Y.; Xie, W. Status and influencing factors of social media addiction in Chinese Medical Care Professionals: A cross-sectional survey. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 888714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulasula, J. Effects of Social Media Addiction on Daily Work Performance of Government Employees. SSRN. 2023. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4519466 (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Hoşgör, H.; Coşkun, F.; Çalişkan, F.; Hoşgör, D.G. Relationship between nomophobia, fear of missing out, and perceived work overload in nurses in Turkey. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 57, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nageshwar, V. Public Perception of nursing as a profession. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 5, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gander, P.; O’Keeffe, K.; Santos-Fernandez, E.; Huntington, A.; Walker, L.; Willis, J. Fatigue and nurses’ work patterns: An online questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 98, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, M.; Yusra, Y.; Shah, N.U. Impact of social media addiction on work engagement and job performance. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2022, 25, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Nagar, D. Relationship between psychological capital and job engagement: A study on public healthcare providers. Indian J. Posit. Psychol. 2022, 13, 352–355. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazawy, E.R.; Mahfouz, E.M.; Mohammed, E.S.; Refaei, S.A. Nurses’ work engagement and its impact on the job outcomes. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2021, 14, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, M.F.; Alrwaitey, R.Z. Work engagement status of registered nurses in pediatric units in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Iglesias, J.J.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Ortega-Moreno, M.; Navarro-Abal, Y. Relationship Between Work Engagement, Psychosocial Risks, and Mental Health Among Spanish Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2021, 8, 627472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Qiao, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, C. Relationship between work engagement and healthy work environment among Chinese ICU nurses: The mediating role of psychological capital. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 6248–6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Long, K.; Shen, H.; Yang, Z.; Yang, T.; Deng, L.; Zhang, J. Resilience, organizational support, and innovative behavior on nurses’ work engagement: A moderated mediation analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1309667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, G.M.; El Nagar, M.A. Work Engagement of staff nurses and its Relation to Psychological Work Stress. J. Nurs. Health Sci. 2019, 8, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebenberg, J.-M.; Scholtz, S.E.; De Beer, L.T. The daily basic psychological need satisfaction and work engagement of nurses: A ‘shortitudinal’ diary study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.T.; Teo, S.T.; Pick, D.; Jemai, M. Cynicism about change, work engagement, and job satisfaction of Public Sector Nurses. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2018, 77, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Horsley, L.; Cao, Y.; Haddad, L.M.; Hall, K.C.; Robinson, R.; Powers, M.; Anderson, D.G. The associations among nurse work engagement, job satisfaction, quality of care, and intent to leave: A national survey in the United States. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2023, 10, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurdiyansyah, E.D.; Harjadi, D.; Karmela, L. The Influence of Meaningful Work and Work Environment on Organizational Commitment Through Work Engagement as a Moderator Variable in the Kuningan Regency Regional Apparatus. J. Soc. Res. 2024, 3, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Hara, Y.; Asakura, K.; Sugiyama, S.; Takada, N.; Ito, Y.; Nihei, Y. Nurses working in nursing homes: A mediation model for work engagement based on job demands-resources theory. Healthcare 2021, 9, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Feng, Z.; Zhu, M.; Yang, J. The study on influencing factors of nurses’ job engagement in 3-Grade Hospitals in east China: A cross-sectional study. Res. Square 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucciarelli, G.; Simeone, S.; Virgolesi, M.; Madonna, G.; Proietti, M.G.; Rocco, G.; Stievano, A. Nursing-Related Smartphone Activities in the Italian Nursing Population: A Descriptive Study. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2019, 37, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Elhai, J.D.; Montag, C.; Wegmann, E.; Rozgonjuk, D. The role of trait and state fear of missing out on problematic social networking site use and problematic smartphone use severity. Emerg. Trends Drugs Addict. Health 2024, 4, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Han, X.; Yu, H.; Wu, Y.; Potenza, M.N. Do men become addicted to internet gaming and women to social media? A meta-analysis examining gender-related differences in specific internet addiction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 113, 106480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M.; Ali, A. Social media addiction among youth: A gender comparison. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2020, 8, 740–748. [Google Scholar]

- Sayyd, S.M.; Zainuddin, Z.A.B.; Ghan, D.Z.B.A.; Altowerqi, Z.M. Sports activities for undergraduate students in Saudi Arabia universities: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Hum. Mov. Sports Sci. 2020, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, S.; Anwer, M.; Mufti, A.A.; Iqbal, M. Investigating how Cultural Contexts Shape Social Media Experiences and their Emotional Consequence. Rev. Educ. Adm. Law 2024, 7, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, A.M.; Harbi, M.M.A.; Alhamidah, A.S.; Alreshidi, Y.Q.; Abdulrahim, O. Association between social media use and depression among Saudi population. Ann. Int. Med. Dent. Res. 2018, 4, 26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.M.; Chang, Y. Stress, depression, and intention to leave among nurses in different medical units: Implications for healthcare management/nursing practice. Health Policy 2012, 108, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakertzis, E.; Myloni, B. Profession as a major drive of work engagement and its effects on job performance among healthcare employees in Greece: A comparative analysis among doctors, nurses, and administrative staff. Health Serv. Manag. Res. 2021, 34, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Odagami, K.; Inagaki, M.; Moriya, K.; Fujiwara, H.; Eguchi, H. Work engagement among older workers: A systematic review. J. Occup. Health 2024, 66, uiad008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Domain | No. of | Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Social Media Networking Addiction scale | 21 | 0.95 |

| 2 | The UWES | 17 | 0.95 |

| Silence | Mean ± SD | Mean% |

|---|---|---|

| 2.33 ± 1.57 | 33.29% |

| 3.57 ± 1.89 | 51.0% |

| 3.17 ± 1.77 | 45.29% |

| 3.08 ± 1.82 | 44.0% |

| Mood modification | ||

| 3.78 ± 1.79 | 54.0% |

| 3.87 ± 1.76 | 55.29% |

| 3.54 ± 1.75 | 50.57% |

| Tolerance | ||

| 3.52 ± 1.74 | 50.29% |

| 3.54 ± 1.76 | 50.57% |

| 2.88 ± 1.69 | 41.14% |

| Withdrawal | ||

| 2.82 ± 1.69 | 40.29% |

| 2.58 ± 1.58 | 36.86% |

| 2.66 ± 1.63 | 38.0% |

| 2.53 ± 1.58 | 36.14% |

| Conflict | ||

| 2.59 ± 1.55 | 37.0% |

| 2.12 ± 1.43 | 30.29% |

| 2.39 ± 1.67 | 34.14% |

| Relapse | ||

| 2.77 ± 1.61 | 39.57% |

| 2.89 ± 1.65 | 41.29% |

| 2.78 ± 1.58 | 39.71% |

| 2.80 ± 1.69 | 40.0% |

| SNAS Domain | Mean ± SD | Mean (%) | Perceived Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silence score | 12.2 ± 5.94 | 43.6% | Low |

| Mood modification score | 11.2 ± 4.84 | 53.3% | Average |

| Tolerance score | 9.93 ± 4.66 | 47.3% | Average |

| Withdrawal score | 10.6 ± 5.97 | 37.9% | Low |

| Conflict score | 7.10 ± 4.11 | 33.8% | Low |

| Relapse score | 11.2 ± 5.95 | 40.0% | Low |

| SNAS total score | 62.2 ± 25.6 | 42.3% | Low |

| Level of Addiction | Score Range | N (%) | Perceived Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥84 | 50 (17.7%) | Low |

| <84 | 233 (82.3%) | High |

| Vigor | Mean ± SD | Mean% |

|---|---|---|

| 3.65 ± 1.69 | 60.83% |

| 3.76 ± 1.58 | 62.67% |

| 3.55 ± 1.62 | 59.17% |

| 3.25 ± 1.84 | 54.17% |

| 3.81 ± 1.65 | 63.50% |

| 4.15 ± 1.62 | 69.17% |

| Dedication | ||

| 4.53 ± 1.59 | 75.50% |

| 4.36 ± 1.57 | 72.67% |

| 4.51 ± 1.63 | 75.17% |

| 4.72 ± 1.61 | 78.67% |

| 4.60 ± 1.58 | 76.67% |

| Absorption | ||

| 4.17 ± 1.60 | 69.50% |

| 3.82 ± 1.75 | 63.67% |

| 3.49 ± 1.85 | 58.17% |

| 4.04 ± 1.64 | 67.33% |

| 3.88 ± 1.68 | 64.67% |

| 3.67 ± 1.85 | 61.17% |

| UWES Domain | Mean ± SD | Mean (%) | Perceived Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vigor score | 3.69 ± 1.36 | 61.5% | Average |

| Dedication score | 4.54 ± 1.46 | 75.7% | Average |

| Absorption score | 3.84 ± 1.43 | 64.0% | Average |

| UWES total score | 3.99 ± 1.22 | 66.5% | Average |

| UWES domain levels | Score range | N (%) |

| UWES Domain | Social Media Networking Addiction | Z-Test | p-Value § | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addiction Mean ± SD | Non-Addiction Mean ± SD | |||

| Vigor score | 3.23 ± 1.58 | 3.79 ± 1.28 | −1.983 | 0.047 ** |

| Dedication score | 4.66 ± 1.29 | 4.52 ± 1.49 | 0.315 | 0.752 |

| Absorption score | 3.28 ± 1.65 | 3.96 ± 1.35 | −2.407 | 0.016 ** |

| UWES total score | 3.49 ± 1.49 | 4.10 ± 1.13 | −2.277 | 0.023 ** |

| Factor | Social Media Addiction | Work Engagement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addiction N (%) (n = 50) | Non Addiction N (%) (n = 233) | Low to Average N (%) (n = 191) | High/Very High N (%) (n = 92) | |

| Age group | ||||

| 37 (74.0%) | 156 (67.0%) | 136 (71.2%) | 57 (62.0%) |

| 13 (26.0%) | 77 (33.0%) | 55 (28.8%) | 35 (38.0%) |

| X2 ; p-value § | 0.943; 0.332 | 2.448; 0.118 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| 16 (32.0%) | 23 (9.9%) | 24 (12.6%) | 15 (16.3%) |

| 34 (68.0%) | 210 (90.1%) | 167 (87.4%) | 77 (83.7%) |

| X2 ; p-value § | 16.966; 0.001 ** | 0.731; 0.393 | ||

| Nationality | ||||

| 41 (82.0%) | 142 (60.9%) | 121 (63.4%) | 62 (67.4%) |

| 9 (18.0%) | 91 (39.1%) | 70 (36.6%) | 30 (32.6%) |

| X2; p-value § | 7.987; 0.005 ** | 0.444; 0.505 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| 18 (36.0%) | 65 (27.9%) | 54 (28.3%) | 29 (31.5%) |

| 32 (64.0%) | 168 (72.1%) | 137 (71.7%) | 63 (68.5%) |

| X2; p-value § | 1.304; 0.253 | 0.316; 0.574 | ||

| Educational Level | ||||

| 11 (22.0%) | 69 (29.6%) | 49 (25.7%) | 31 (33.7%) |

| 39 (78.0%) | 164 (70.4%) | 142 (74.3%) | 61 (66.3%) |

| X2; p-value § | 1.177; 0.278 | 1.980; 0.159 | ||

| Years of Working Experience | ||||

| 16 (32.0%) | 71 (30.5%) | 62 (32.5%) | 25 (27.2%) |

| 34 (68.0%) | 162 (69.5%) | 129 (67.5%) | 67 (72.8%) |

| X2; p-value § | 0.045; 0.832 | 0.815; 0.367 | ||

| Unit of Assignment | ||||

| 15 (30.0%) | 58 (24.9%) | 46 (24.1%) | 27 (29.3%) |

| 10 (20.0%) | 66 (28.3%) | 60 (31.4%) | 16 (17.4%) |

| 25 (50.0%) | 109 (46.8%) | 85 (44.5%) | 49 (53.3%) |

| X2; p-value § | 1.569; 0.456 | 6.219; 0.045 ** | ||

| Working Shift | ||||

| 37 (74.0%) | 137 (58.8%) | 115 (60.2%) | 59 (64.1%) |

| 2 (04.0%) | 16 (6.9%) | 12 (06.3%) | 6 (06.5%) |

| 11 (22.0%) | 80 (34.3%) | 64 (33.5%) | 27 (29.3%) |

| X2; p-value § | 4.027; 0.134 | 0.495; 0.781 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boukari, Z.I.; Elseesy, N.A.M.; Felemban, O.; Alharazi, R. Between Clicks and Care: Investigating Social Media Addiction and Work Engagement Among Nurses in Saudi Arabia. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15030084

Boukari ZI, Elseesy NAM, Felemban O, Alharazi R. Between Clicks and Care: Investigating Social Media Addiction and Work Engagement Among Nurses in Saudi Arabia. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(3):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15030084

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoukari, Zahour Ismael, Naglaa Abdelaziz Mahmoud Elseesy, Ohood Felemban, and Ruba Alharazi. 2025. "Between Clicks and Care: Investigating Social Media Addiction and Work Engagement Among Nurses in Saudi Arabia" Nursing Reports 15, no. 3: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15030084

APA StyleBoukari, Z. I., Elseesy, N. A. M., Felemban, O., & Alharazi, R. (2025). Between Clicks and Care: Investigating Social Media Addiction and Work Engagement Among Nurses in Saudi Arabia. Nursing Reports, 15(3), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15030084