Qualitative Study of Maternity Healthcare Vulnerability Based on Women’s Experiences in Different Sociocultural Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Characteristics of the Women Participants

2.3. Interview Design

2.4. Data Analysis

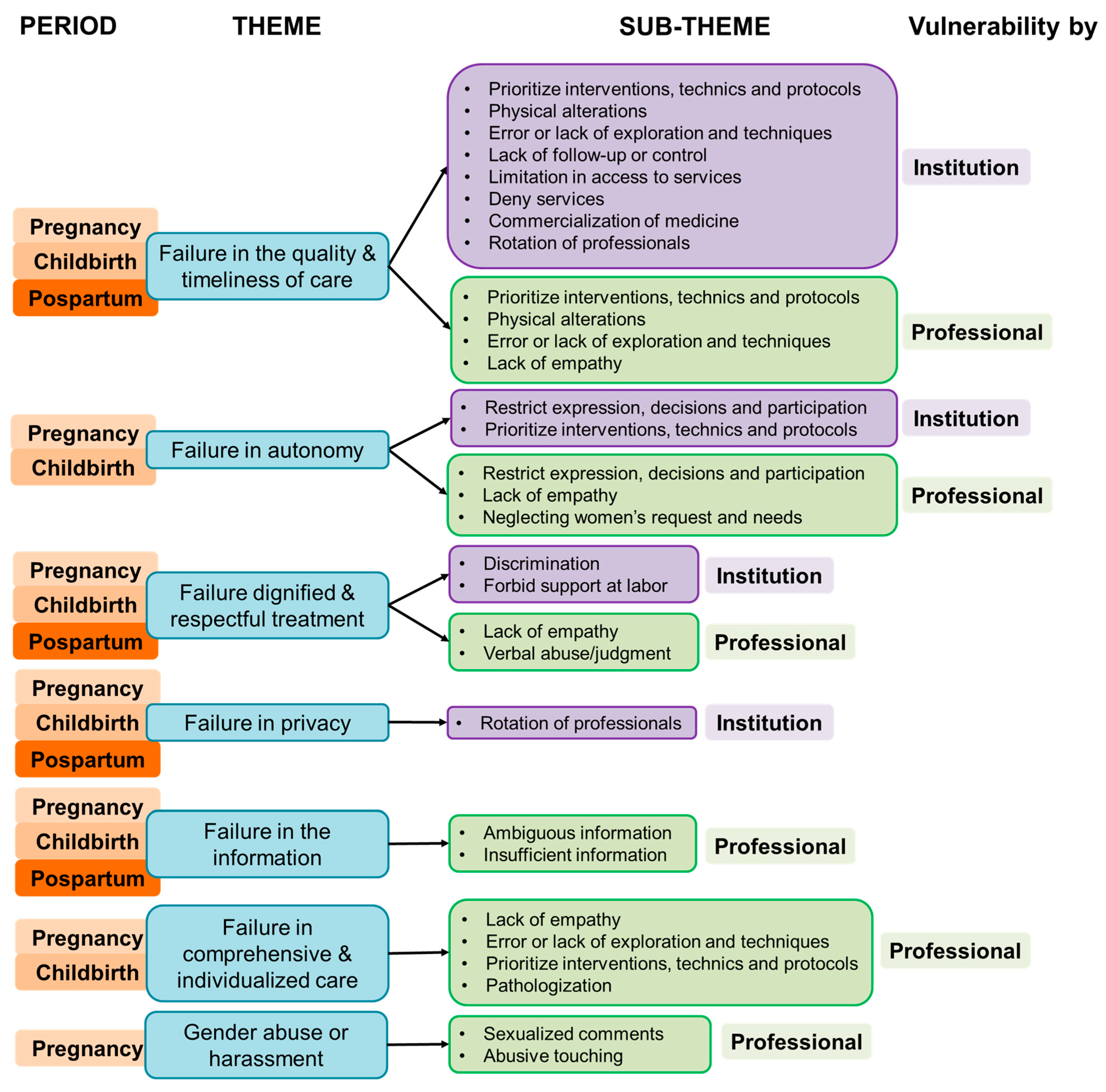

3. Results

3.1. Experience of Vulnerability and Knowledge Related to Maternity Rights

“I have heard from women who have many children that physicians begin to generate the rejection that they get pregnant all the time, and they begin to make comments that belittle that condition”.(Transcript I—C3).

Physical violence: “When they [physicians] have to perform labor instrumentation in the ways they do it”.(Transcript I—S3).

Problems with access to healthcare: “I know many cases where it was 3 or 4 in the afternoon, they had been starving all day, and they had not been taken to an operating room because there was no order”.(Transcript II—C2).

Problems with professionals: “The physician who assist me, I don’t know what was on his mind, and he did an ultrasound and told me: no, the baby is growing in the whole scar from the previous C-section, it can’t be born; I think that this week you will have a spontaneous abortion or come a day and I will perform the abortion because it can’t be born. Another doctor saw me, did an ultrasound and told me: no, that there was a 4 mm detachment, but with hormones and care it would be fine. And so, it was”.(Transcript III—C1).

No compliance with safety: “I thought, they will induce labor, they will be there observing me, and everything will be very controlled. But it is not like that. My blood pressure dropped, and nobody noticed”.(Transcript II—S1).

“They [physicians/nurses] talk to you as: it’s your fault, you looked for it. Literally, one day a nurse told me: well, why did you open your legs? [refers to her pregnancy].”… “They [physicians/nurses] don’t listen, they don’t pay attention to me simply because: he’s the physician. I listen to my body and understand many things, I know that something is changing and that something is suddenly not right”.(Transcript III—C2).

“They said [physicians/nurses]: you are fatter than a pig, you can’t be that fat, like a seal. Ugly things!”.(Transcript III—S1).

“The right to care anywhere, because some time, I go and need to get a health card-insurance, but I can’t if I don’t have a valid passport, which means a lot of documentation”.(Transcript III—S2).

“Those vaginal examinations that they [physician] do to me all the time… the truth was very traumatic… I don’t know if that is medically necessary or if there is another way… that is what I felt like they were putting their hand, fist and elbow inside of me”.(Transcript IV—C3).

“As they [physician/nurse] are in favor of vaginal birth, they make me endure until I almost die for natural birth occur. But I don’t know, let the mother’s priority prevail”.(Transcript IV—S1).

“I pushed, and because of the epidural, I couldn’t apply enough force… The physician had to get on top of me and use their arms to press down on my stomach so that the baby would come out. I remember that as being really awful… if it wasn’t for the baby dying, nobody should do this, because I had a bad time and was uncomfortable feeling and I’m in a beautiful moment and I’m there dying, because it hurts when they press down on your stomach, it doesn’t hurt when you give birth”.(Transcript IV—S3).

“A nurse said: you abandoned your daughter here. Financially, she didn’t know how I was doing; emotionally, also, she didn’t know how I was. If it would be for me, I would have spent 24 h there. But I had another newborn at home, I didn’t have anyone to take care of her, and I knew that the baby who was in the clinic was surrounded by professionals. I went twice a day. The truth is I felt really bad, I didn’t abandon my daughter, I just couldn’t do it”.(Transcript V—C2).

“They [nurse] are like-you have the child, and you have to know-, but you are not born knowing. They should put themselves in the place of the woman who has just given birth or who does not even know how to hold the child”.(Transcript V—S2).

“I am extremely worried about my baby because in the hypothetical case that he has Down syndrome, what can I do? Do I continue or not? And the other person [health professional] only thinks about the 600 euros for the test”.(Transcript V—S3).

Gender harassment: “They [health professionals] exceed with women, for example by touching physically or commenting on their physical appearance”.(Transcript VI—C1).

Lack of communication: “They [health professional] say ‘Get ready to not sleep’ [ironically]. I say: ‘What?’. I can’t imagine the magnitude of what is coming. They should sit people down and tell them: You are not going to sleep because of this, organize your time, prepare yourself like this, create a routine like this”. Bad communication: “He [physician] told me: a normal pregnancy is just a baby; this is already starting badly [multiple pregnancy]”.(Transcript VI—C2).

Bad communication: “The first time I tested positive for toxoplasmosis, she [physician] could not explain it to me, and the truth is I was scared, I cried”.(Transcript VI—C3).

“The bad thing is that I did not have a person to trust, to go to the same professional, and I can tell them. They are guided by what the previous one has written”. Lack of attention: “I asked: please, I feel terrible, if I have already dilated completely and the baby has not come down, is there any solution? As if they [health professionals] hadn’t heard me”.(Transcript VI—S1).

3.2. Perception of Psychosocial Factors Influencing OB/GYN Vulnerability

Lack of maternity and hospitalization experience and low socioeconomic conditions: “In girls or very young women who become pregnant or who live in a village, who know very little”.(Transcript VII—C1).

Expectations and beliefs of idealization of motherhood: “Motherhood was the most beautiful thing in the world, but no, postpartum depression exists. Motherhood has been romanticized a lot”. Changes due to motherhood: “It is very hard, it is very heavy, it is three months in which you do not sleep, literally I did not sleep at all, and I have to take care of two babies, when many times I do not even know how to take care of yourself”.(Transcript VII—C2).

Expectations and beliefs of motherhood: “I think that everything is automatic when you have your first child, but no, there are things that are definitely enough complex”.(Transcript VII—C3).

Emotional lability and alteration of physical state: “You have the doors open [in the healthcare center], what am I hearing? -Delivery room number I don’t know what, running to the operating room- it makes me even more anxious because I don’t feel well, I was afraid because I didn’t know what was really going to happen, and I was hearing external things, and I didn’t know if that was going to happen to me too”. Inconsistent information: “When I was pregnant, it seems like everyone tells me something different, I really don’t know what to believe”.(Transcript VII—S1).

Lifestyle changes by motherhood: “I put aside my own things, the professional side in my case, and to ensure that they [children] are not left alone or are not in daycare or with other people all day, it is a bit of a sacrifice”.(Transcript VII—S2).

Emotional lability: “I have my emotions so on edge, it’s uncontrollable”.(Transcript VII—S3).

Positive attitude: “I didn’t have a bad life. Many factors depended on my emotional state, on whether my daughters were well. I tried to be as calm as possible; I helped the nurses; I helped them do things because I had nothing else to do [during hospitalization]”.(Transcript VIII—C2).

“I had the premium plan [health insurance], I had direct access to the gynecologists and obstetricians. I didn’t have to go around in circles as I know other women sometimes have to”. Prioritization to women: “That I can have a phone number, or a pediatrician, or a specific gynecologist-obstetrician… something much closer than schematized, than having to make an appointment and having to travel. Sometimes so much procedure is a bit complex for the situation of a state of pregnancy”. Information, education and assertive communication: “Breastfeeding was not easy either… the advice from the nurses because at first I did not have any milk, that really helped me a lot… they teach you how to do it”. Family support: “They [health institution] allowed my husband to be present at every moment of the process, including allowing him to enter the labor room without problems”.(Transcript VIII—C3).

Motivation: “It was a process that is an insemination [her pregnant], and I achieve it, of course it is the greatest happiness. And then if I have a super good pregnancy, which I didn’t vomit, I could live a normal life. So, I am much more motivated because I can live my normal life and added to that I was going to have a baby”.(Transcript VIII—S1).

Active participation during care: “You have to talk and say what you feel as a mother and be taken into account”. Adherence to the recommendations of health professionals: “The willingness to change my routine a little. When I was pregnant, I have to do a number of things, both with regard to food and taking medicine”.(Transcript VIII—S2).

Previous experience: “I was not very nervous, and I was more aware of everything that was happening”. Social support: “A friend who works in a hospital told me: come and we’ll talk to the gynecologist and see what happens”. Constant monitoring: “They [health institution] sent me to a physician. Then, I had a couple of problems with the baby because she had epileptic seizures, and the physician immediately sent me to a psychologist, and they have been treating me very well”.(Transcript VIII—S3).

Poor emotional regulation: “If you work under stress… in the end you pay with the least guilty person in very delicate situations, because childbirth is a situation that you have to take carefully. Each case is a different story, and you cannot treat people badly because you are having a bad day [regarding health professionals]”. Non-compliance with care protocols: “They [nurse] just suture that up, they didn’t check it [vagina]. The gynecologist looked at me before discharging me: this is perfect; -how perfect?—Then I was worried”.(Transcript IX—S1).

Lack of empathy: “They [health professionals] should have a little more empathy… to put themselves in the place of the woman who has just given birth and teach her”.(Transcript IX—S2).

Communication skills deficiencies: “The midwife would come and say: I like quick and painless births… and I would say: me too. He wouldn’t say anything else. And I would only stick with quick and painless”.(Transcript IX—S3).

“Each patient needs to receive more personalized attention because each case is different. Maybe what I need someone else doesn’t need. They [physician] can’t treat everyone the same”.(Transcript X—S1).

Participation of women in its care: “They [health professionals] said to me: do you want to see it? Me: yes. They put a mirror; I could see it… it was fantastic. In fact, they said to me: when the baby is coming out, put your hands out so you can hold it. As soon as the baby came out, I held her with my hands and put her on my chest. I have the whole super nice memory”.(Transcript X—S3).

Poor working conditions: “Maybe, they [physician] get paid too late… or because the workday is too long, and they are tired. If their rights are violated, they are not going to be treated with the best attitude”.(Transcript XI—C2).

Lack of humanization: “They should be trained a little better in care… a module on humanity, on how to treat the person from a psychological, sensitive point of view, beyond the procedure”.(Transcript XI—C3).

“I also expected that the same specialists would follow up with you until the end, but that is not true”.(Transcript XI—S1).

Lack of organization: “It is true that they [health institutions] put a lot of pressure on the professional: -you have to attend to so many patients a day-… they have to hire more physician, because in the end, they [physician] cannot do miracles and they cannot attend to you in 1 min, it is impossible”.(Transcript XI—S3).

4. Discussion

4.1. Implication for Healthcare Practice

4.2. Strengths and Limitation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jojoa-Tobar, E.; Cuchumbe-Sánchez, Y.D.; Ledesma-Rengifo, J.B.; Muñoz-Mosquera, M.C.; Suarez-Bravo, J.P. Violencia Obstétrica: Haciendo Visible Lo Invisible. Rev. De La Univ. Ind. De Santander Salud 2019, 51, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohren, M.A.; Vogel, J.P.; Hunter, E.C.; Lutsiv, O.; Makh, S.K.; Souza, J.P.; Aguiar, C.; Saraiva Coneglian, F.; Diniz, A.L.A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; et al. The Mistreatment of Women during Childbirth in Health Facilities Globally: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Roosmalen, J.; van den Akker, T. Continuous and Caring Support Right Now. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 123, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jardim, D.M.B.; Modena, C.M. Obstetric Violence in the Daily Routine of Care and Its Characteristics. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2018, 26, e3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Villaseñor, A. Percepción Del Parto Humanizado En Pacientes En Periodo de Puerperio. Rev. Med. Inst. Mex. Seguro Soc. 2021, 58, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedam, S.; Stoll, K.; Taiwo, T.K.; Rubashkin, N.; Cheyney, M.; Strauss, N.; McLemore, M.; Cadena, M.; Nethery, E.; Rushton, E.; et al. The Giving Voice to Mothers Study: Inequity and Mistreatment during Pregnancy and Childbirth in the United States. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.; Cignacco, E.; Monteverde, S.; Trachsel, M.; Raio, L.; Oelhafen, S. ‘We Felt like Part of a Production System’: A Qualitative Study on Women’s Experiences of Mistreatment during Childbirth in Switzerland. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-de la Torre, H.; González-Artero, P.N.; Muñoz de León-Ortega, D.; Lancha-de la Cruz, M.R.; Verdú-Soriano, J. Cultural Adaptation, Validation and Evaluation of the Psychometric Properties of an Obstetric Violence Scale in the Spanish Context. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 1368–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Galiano, J.M.; Martinez-Vazquez, S.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J.; Hernández-Martinez, A. The Magnitude of the Problem of Obstetric Violence and Its Associated Factors: A Cross-Sectional Study. Women Birth 2021, 34, e526–e536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Fernandez, C.S.; de la Calle, M.; Arribas, S.M.; Garrosa, E.; Ramiro-Cortijo, D. Factors Associated with Obstetric Violence Implicated in the Development of Postpartum Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 1553–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Galiano, J.M.; Delgado-Rodríguez, M. The Relegated Goal of Health Institutions: Sexual and Reproductive Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Fernández, C.S.; de la Calle, M.; Camacho, P.A.; Arribas, S.M.; Garrosa, E.; Ramiro-Cortijo, D. Psychometric Reliability to Assess the Perception of Women’s Fulfillment of Maternity Rights. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 2248–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallana Sala, M.V.V. “Es Rico Hacerlos, Pero No Tenerlos”: Análisis de La Violencia Obstétrica Durante La Atención Del Parto En Colombia. Rev. Cienc. De La Salud 2019, 17, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begley, K.; Daly, D.; Panda, S.; Begley, C. Shared Decision-making in Maternity Care: Acknowledging and Overcoming Epistemic Defeaters. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2019, 25, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millogo, T.; Kourouma, K.R.; Diallo, A.; Agbre-Yace, M.L.; Baldé, M.D.; Kouanda, S. Effectiveness of the World Health Organization Safe Childbirth Checklist (WHO-SCC) in Preventing Poor Childbirth Outcomes: A Study Protocol for a Matched-Pair Cluster Randomized Control Trial. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Banda, A.; De la Torre Rodríguez, F.A. Violencia Obstétrica. Artículo de Revisión. Lux. Médica 2019, 14, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalley, A.A. Layers of Inequality: Gender, Medicalisation and Obstetric Violence in Ghana. Int. J. Equity Health 2024, 23, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research (SRH). The Prevention and Elimination of Disrespect and Abuse during Facility-Based Childbirth. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-RHR-14.23 (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Kade, K.; Levers, L.; Vitolo, K.; Whipkey, K.; Copeland, D.; Khalil, M.; Browning, M.; Emson, M.; Ware, M. Respectful Maternity Care. Universal Rights of Women and Newborns; White Ribbon Alliance, Ed.; White Ribbon Alliance: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Maternal; Newborn; Child; Adolescent Health; Ageing (MCA); Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research (SRH). WHO Recommendations: Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550215 (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Maternal; Newborn; Child; Adolescent Health; Ageing (MCA); Nutrition and Food Safety (NFS); Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research (SRH). WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience: Executive Summary. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-RHR-16.12 (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- McCauley, M.; White, S.; Bar-Zeev, S.; Godia, P.; Mittal, P.; Zafar, S.; van den Broek, N. Physical Morbidity and Psychological and Social Comorbidities at Five Stages during Pregnancy and after Childbirth: A Multicountry Cross-Sectional Survey. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e050287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Fernández, C.S.; Camacho, P.A.; de la Calle, M.; Arribas, S.M.; Garrosa, E.; Ramiro-Cortijo, D. Analysis of Maternity Rights Perception: Impact of Maternal Care in Diverse Socio-Health Contexts. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo Sanguino, N. Fenomenología Como Método de Investigación Cualitativa: Preguntas Desde La Práctica Investigativa. Rev. Latinoam. Metodol. Investig. Soc. 2021, 20, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in Qualitative Research: Exploring Its Conceptualization and Operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukke, G.G.; Gurara, M.K.; Boynito, W.G. Disrespect and Abuse of Women during Childbirth in Public Health Facilities in Arba Minch Town, South Ethiopia—A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0205545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Castro, M.; Salinero-Rates, S. The Continuum of Violence against Women: Gynecological Violence within the Medical Model in Chile. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2023, 37, 100891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonovic, D. A Human-Rights Based Approach to Mistreatment and Obstetric Violence During Childbirth. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/calls-for-input/report-human-rights-based-approach-mistreatment-and-obstetric-violence-during (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- de Souza, K.J.; Rattner, D.; Gubert, M.B. Institutional Violence and Quality of Service in Obstetrics Are Associated with Postpartum Depression. Rev. Saude Publica 2017, 51, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand-Guillaume-Perrenoud, J.A.; Origlia, P.; Cignacco, E. Barriers and Facilitators of Maternal Healthcare Utilisation in the Perinatal Period among Women with Social Disadvantage: A Theory-Guided Systematic Review. Midwifery 2022, 105, 103237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, T.C.; Contreras, M.A.; Villarroel, D.L.; Rivera, M.S.; Bravo, V.P.; Cornejo, A.M. Bienestar Materno Durante El Proceso de Parto: Desarrollo y Aplicación de Una Escala de Medición. Rev. Chil. Obstet. Ginecol. 2008, 73, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz Carreño, J.M.; Cornejo-Moreno, M.J.; Ortiz-Contreras, J. Interacción Entre El Equipo de Salud y Las Mujeres En Sus Experiencias de Parto: Scoping Review. MUSAS Rev. De Investig. En Mujer Salud Y Soc. 2024, 9, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Alexandria, S.T.; de Oliveira, M.d.S.S.; Alves, S.M.; Bessa, M.M.M.; Albuquerque, G.A.; Santana, M.D.R. La Violencia Obstétrica Bajo La Perspectiva de Los Profesionales de Enfermería Involucrados En La Asistencia al Parto. Cult. Cuid. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Manzano, G.M. El Derecho Penal Como Medio de Prevención de La Violencia Obstétrica En México. Resultados al 2018. MUSAS 2019, 4, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula, E.; Alves, V.H.; Rodrigues, D.P.; Felicio, F.d.C.; de Araújo, R.C.B.; Chamilco, R.A.d.S.I.; Almeida, V.L.M. Obstetric Violence and the Current Obstetric Model, in the Perception of Health Managers. Texto Contexto-Enferm. 2020, 29, e20190248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steetskamp, J.; Treiber, L.; Roedel, A.; Thimmel, V.; Hasenburg, A.; Skala, C. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Following Childbirth: Prevalence and Associated Factors—A Prospective Cohort Study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 306, 1531–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belizán, J.M.; Miller, S.; Williams, C.; Pingray, V. Every Woman in the World Must Have Respectful Care during Childbirth: A Reflection. Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paravic-Klijn, T.; Burgos-Moreno, M. Prevalencia de Violencia Física, Abuso Verbal y Factores Asociados En Trabajadores/as de Servicios de Emergencia En Establecimientos de Salud Públicos y Privados. Rev. Med. Chil. 2018, 146, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo-Nieto, N.; Herrera-Medina, R.; Fuertes-Bucheli, J.F.; Osorio-Murillo, O.; Castro-Valencia, C. Mejoramiento de La Lactancia Materna Exclusiva a Través de Una Estrategia de Información y Comunicación Prenatal y Posnatal, Cali (Colombia): 2014–2017. Univ. Salud 2023, 26, E1–E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loezar-Hernández, M.; Briones-Vozmediano, E.; Gea-Sánchez, M.; Otero-García, L. Percepción de La Atención Sanitaria En La Primera Experiencia de Maternidad y Paternidad. Gac. Sanit. 2022, 36, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Sáez, J.; Catalán-Matamoros, D.; Fernández-Martínez, M.M.; Granados-Gámez, G. La Comunicación y La Satisfacción de Las Primíparas En Un Servicio Público de Salud. Gac. Sanit. 2011, 25, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obregón, N.; Armenta Hurtarte, C.; Harari, D.; Ortíz-Izquierdo, R. Maternidad Cuestionada: Diferencias Sobre Las Creencias Hacia La Maternidad En Mujeres. Rev. De Psicol. 2020, 19, 047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpinelli, L.; Savarese, G. Negative/Positive Emotions, Perceived Self-Efficacy and Transition to Motherhood during Pregnancy: A Monitoring Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Backer, K.; Pali, A.; Challacombe, F.L.; Hildersley, R.; Newburn, M.; Silverio, S.A.; Sandall, J.; Howard, L.M.; Easter, A. Women’s Experiences of Attempted Suicide in the Perinatal Period (ASPEN-Study)—A Qualitative Study. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, I.H.; Simonsen, M.; Trillingsgaard, T.; Pontoppidan, M.; Kronborg, H. First-Time Mothers’ Confidence Mood and Stress in the First Months Postpartum. A Cohort Study. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2018, 17, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Mendiola, R.B.; Reynaga-Ornelas, L.; Jiménez-Garza, O.A.; Dávalos-Pérez, A.; Rodríguez-Lugo, S. Diferencias En La Calidad de Vida Por Trimestre Del Embarazo En Un Grupo de Adolescentes Argentinas. Acta Univ. 2015, 24, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio Castaño, J.H.; Calderón Bejarano, H.; Noguera Ortiz, N.Y. Convertirse En Madre y Preparación Para La Maternidad. Un Estudio Cualitativo Exploratorio. Investig. Enfermería Imagen Desarro. 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobe, H.; Kita, S.; Hayashi, M.; Umeshita, K.; Kamibeppu, K. Mediating Effect of Resilience during Pregnancy on the Association between Maternal Trait Anger and Postnatal Depression. Compr. Psychiatry 2020, 102, 152190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, R.; Rodríguez-Llagüerri, S.; Presado, M.H.; Baixinho, C.L.; Martín-Vázquez, C.; Liebana-Presa, C. Autoeficacia En La Lactancia Materna y Apoyo Social: Un Estudio de Revisión Sistemática. New Trends Qual. Res. 2023, 18, e875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.P.; Narayan, A.J. Pregnancy as a Period of Risk, Adaptation, and Resilience for Mothers and Infants. Dev. Psychopathol. 2020, 32, 1625–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paricio del Castillo, R.; Polo Usaola, C. Maternity and Maternal Identity: Therapeutic Deconstruction of Narratives. Rev. Asoc. Esp. Neuropsiq. 2020, 40, 33–54. [Google Scholar]

| Women | Context | Status | Age | Occupation | Healthcare Center | Pregnancy | Labor | Parity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | Colombia | Married | 28 | Employed | Public and Private | Single | C-section in 2022 | 2 |

| C2 | Colombia | Single | 22 | Unemployed | Public | Multiple | C-section in 2019 | 1 |

| C3 | Colombia | Married | 35 | Employed | Public and Private | Single | Vaginal in 2022 | 1 |

| S1 | Spain | Single | 38 | Employed | Public | Single * | Vaginal in 2019 | 1 |

| S2 | Spain | Married | 30 | Unemployed | Public | Single | C-section in 2023 | 2 |

| S3 | Spain | Married | 33 | Employed | Public and Private | Single | Vaginal in 2024 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva-Fernández, C.S.; Garrosa, E.; Ramiro-Cortijo, D. Qualitative Study of Maternity Healthcare Vulnerability Based on Women’s Experiences in Different Sociocultural Context. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15030105

Silva-Fernández CS, Garrosa E, Ramiro-Cortijo D. Qualitative Study of Maternity Healthcare Vulnerability Based on Women’s Experiences in Different Sociocultural Context. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(3):105. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15030105

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva-Fernández, Claudia Susana, Eva Garrosa, and David Ramiro-Cortijo. 2025. "Qualitative Study of Maternity Healthcare Vulnerability Based on Women’s Experiences in Different Sociocultural Context" Nursing Reports 15, no. 3: 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15030105

APA StyleSilva-Fernández, C. S., Garrosa, E., & Ramiro-Cortijo, D. (2025). Qualitative Study of Maternity Healthcare Vulnerability Based on Women’s Experiences in Different Sociocultural Context. Nursing Reports, 15(3), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15030105