Bridging the Gap: A Phenomenological Study of Transfer Students’ Journey into Professional Nursing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

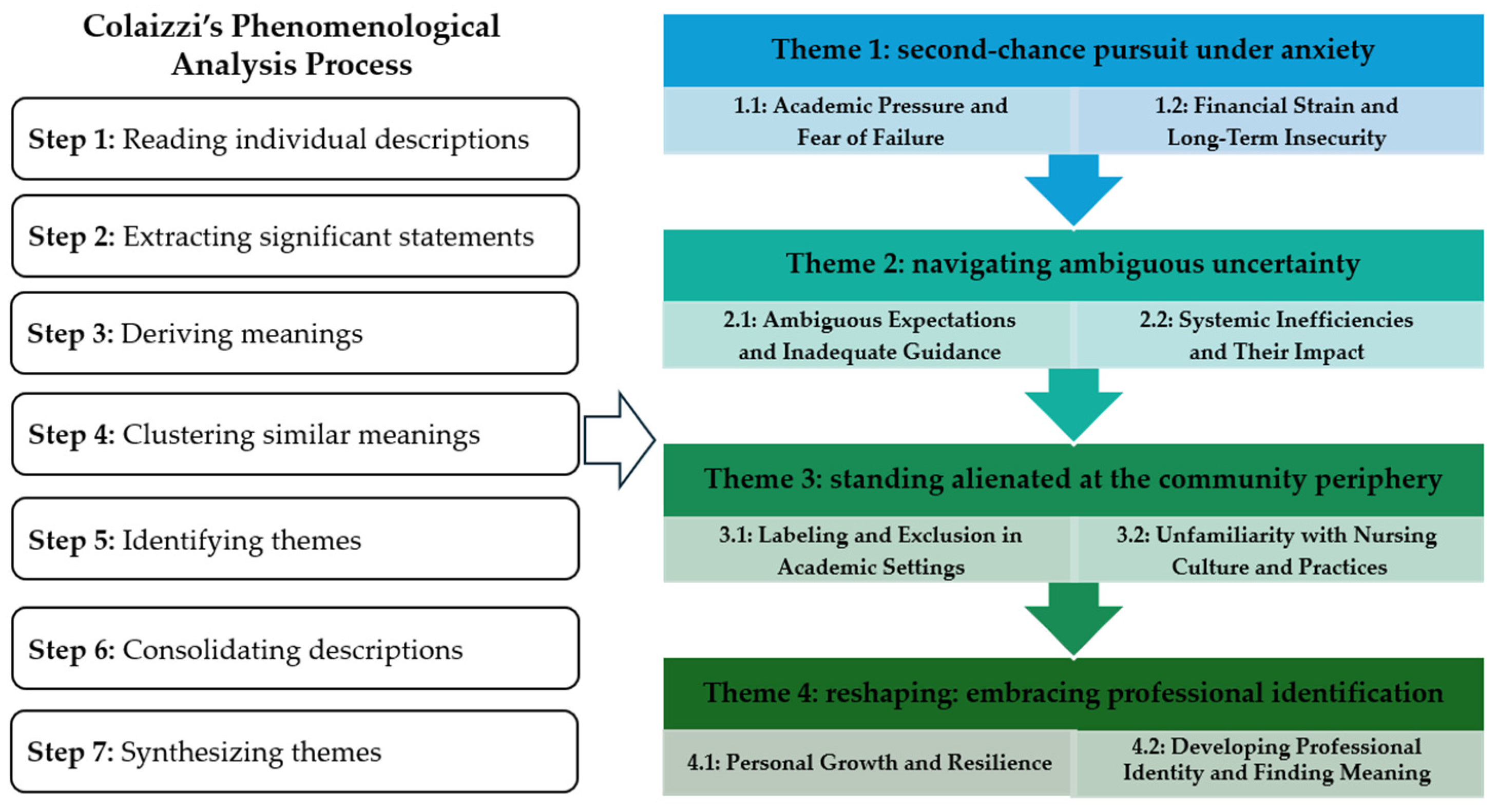

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

- Theme 1: second-chance pursuit under anxiety

“In Korea’s tough job market, age really matters. As an older student, I feel so much pressure to do well academically. I’m older than my classmates. If my grades aren’t good, finding a job will be hard. I can’t afford to mess up, and it makes me anxious. I can’t sleep.”

“I thought my STEM background would mean better grades in nursing. But my grades are lower than I expected. It’s frustrating—I need to study more.”

“I thought I knew how college systems worked, but clinical trials have been tough … I’m always worried about making mistakes, so I double-check everything.”

“Sometimes, I find myself obsessing over small tasks, acting compulsively even for minor things.”

“Tuition again, and I still owe money from my previous course.”

“Starting later in life makes me want to catch up quickly. Nursing isn’t highly compensated, and I’m worried it won’t be enough to support a family.”

- Theme 2: navigating ambiguous uncertainty

“Professors may think we already know things, but I am not sure what I have learned.”

“Nursing has its own language, and it feels like only students who’ve been studying it from the start really get it. So, I don’t know.”

“The administrative office didn’t provide clear explanations, even for basic requirements like antibody tests.”

“If my credits don’t transfer, it delays my graduation and disrupts everything I have planned.”

“Hands-on patient care. Right. I don’t know how to be confident with patients or even where to start with bedside manners. It’s overwhelming.”

- Theme 3: standing alienated at the community periphery

“They always call me a ’transfer student.’ I just want to be treated like others.”

“When someone says, ‘We learned this in freshman year,’ it’s like being reminded that I don’t belong yet.”

“For a group project, all the transfer students were put together. It felt like no one wanted to work with us.”

“Can you believe someone on the online community board called us ’free riders’? It was hurtful.”

“I didn’t know we needed candles for the pin ceremony or that hand-me-down scrubs were a thing. It just made me feel even more like an outsider.”

“My professor said my clinical rotation report lacked a nursing perspective. It made me wonder if I’ll ever fit in.”

- Theme 4: reshaping: embracing professional identification

“I’ve learned to regulate my emotions better when working with my patients. Staying composed has been a major milestone for me.”

“I’ve developed greater patience to face difficult situations, even when I felt like giving up.”

“I’m discovering ways to solve problems I never imagined I could handle before. It’s like unlocking new potential.”

“…Knowing my limits and reaching out for support has helped me feel more balanced.”

“My perspective has shifted. Now, I think about what the patients need first.”

“Accepting mistakes as part of the learning process has been key to my growth as a nurse.”

“In clinical courses, I’m starting to see myself as a future nurse. Each day feels more affirming.”

“My previous major adds value to how I approach nursing. It gives me perspectives others might not have.”

“I keep remembering why I chose this path. The challenges are tough, but they remind me why I’m here as a nurse.”

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheong, H.S.; Kwon, K.T.; Hwang, S.; Kim, S.-W.; Chang, H.-H.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, B.; Lee, S.; Park, J.; Heo, S.T. Workload of Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Outbreak in Korea: A Nationwide Survey. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2022, 37, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S. The Current Status of the Administrative Dispositions of Nurses: A Nationwide Survey in South Korea. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 29, e170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Lee, B. Psychological Workplace Violence and Health Outcomes in South Korean Nurses. Workplace Health Saf. 2022, 70, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.; Lee, H.-J. South Korean Nurses’ Experiences with Patient Care at a COVID-19-Designated Hospital: Growth after the Frontline Battle against an Infectious Disease Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, N. Students’ College Life Adaptation Experiences in the Accelerated Second-Degree Bachelor of Science in Nursing Program in South Korea. J. Korean Acad. Soc. Nurs. Educ. 2022, 28, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. Republic of Korea. Partial Amendment to the Higher Education Act; Article 15-2 (Postponement of Acquisition of Bachelor’s Degrees). 2018. Available online: https://law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engLsSc.do?menuId=2&query=HIGHER%20EDUCATION%20ACT#EJP8:0 (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Schwartz, J.; Gambescia, S.F.; Patton, C. Impetus and Creation of an Accelerated Second-Degree Baccalaureate Nursing Program Readmission Policy. SAGE Open Nurs. 2017, 3, 2377960817704770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, A.; Shimoda, K.; Kawabata, A.; Oku, H.; Horiuchi, S. Evaluation of the First Accelerated Bachelor of Science in Nursing Program as a Second Career in Japan. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 111, 105275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Bai, Y.; Bai, Y.; Ma, W.; Yang, X.; Li, J. Factors Influencing Training Transfer in Nursing Profession: A Qualitative Study. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, P. Experiences of Nursing Students in a Bachelor of Nursing Program as They Transition from Enrolled Nurse to Registered Nurse. Ph.D. Thesis, Murdoch University, Murdoch, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ching, S.S.; Zhang, L.W.; Guan, G.Y.; Cheung, K. Challenges of University Nursing Transfer Students in an Asian Context: A Qualitative Study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dante, A.; Ferrão, S.; Jarosova, D.; Lancia, L.; Nascimento, C.; Notara, V.; Pokorna, A.; Rybarova, L.; Skela-Savič, B.; Palese, A. Nursing Student Profiles and Occurrence of Early Academic Failure: Findings from an Explorative European Study. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 38, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.G.; Kwon, S.; Park, H.-J. The Influence of Life Stress, Ego-Resilience, and Spiritual Well-Being on Adaptation to University Life in Nursing Students. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2017, 18, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, C. Experiences of Transfer Students in a Collaborative Baccalaureate Nursing Program. Community Coll. Rev. 2005, 33, 22–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morosanu, L.; Handley, K.; O’Donovan, B. Seeking Support: Researching First-year Students’ Experiences of Coping with Academic Life. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2010, 29, 665–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C. Creating Inclusive Campus Communities: The Vital Role of Peer Mentorship in Inclusive Higher Education. Metrop. Univ. 2017, 28, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ralph, N.; Birks, M.; Chapman, Y.; Muldoon, N.; McPherson, C. From EN to BN to RN: An exploration and analysis of the literature. Contemp. Nurse 2013, 43, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, L.; Mitchell, C.; John WS, T. The transition experience of Enrolled Nurses to a Bachelor of Nursing at an Australian university. Contemp. Nurse 2011, 38, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boelen, M.; Kenny, A. Supporting enrolled nurse conversion—The impact of a compulsory bridging program. Nurse Educ. Today 2009, 29, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter-Wenzlaff, L.J.; Froman, R.D. Responding to Increasing RN Demand: Diversity and Retention Trends Through an Accelerated LVN-to-BSN Curriculum. J. Nurs. Educ. 2008, 47, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tower, M.; Cooke, M.; Watson, B.; Buys, N.; Wilson, K. Exploring the Transition Experiences of Students Entering into Preregistration Nursing Degree Programs with Previous Professional Nursing Qualifications: An Integrative Review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 1174–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Lee, B. The Relationship between Satisfaction with Clinical Practice and Clinical Performance Ability for Nursing Students. Int. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2014, 14, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Youn, Y.J.; Lee, J. The Effect of Clinical Practice Transitional Shock and Resilience on Academic Burnout of Nursing Students. Korean Assoc. Learn.-Centered Curric. Instr. 2019, 19, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Yang, S.C. Professional socialisation of nursing students in a collectivist culture: A qualitative study. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, K.R.; Cha, E.J.; Kim, Y.H. The Lived Experience of a Student Transferring into the Nursing Program. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2003, 33, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.J.; Kim, S.; Byun, E.K. The Experiences of Students Transferring into the Nursing Program at Local Universities. J. Fish. Mar. Sci. Educ. 2016, 28, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Park, K.S.; Kim, Y.H.; Jeong, Y.J. The Experiences of Graduates Who Transferred to a Bachelor of Science in Nursing Program at a College. Korean Soc. Nurs. Res. 2023, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.J.; Jeon, M.K.; Kim, Y.S. Types of Adaptation to College Life for Transfer Nursing Students—Using Q Methodology. Crisisonomy 2017, 13, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, R.; Rodriguez, A.; King, N. Colaizzi’s Descriptive Phenomenological Method. Psychologist 2015, 28, 643–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S. The Effect of Emotional Intelligence and Self-Efficacy on Clinical Competence of the Nursing Students. Int. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2015, 15, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vabo, G.; Slettebø, Å.; Fossum, M. Nursing students’ professional identity development: An integrative review. Nord. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 42, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, C.; Wall, P.; Batt, S.; Bennett, R. Understanding perceptions of nursing professional identity in students entering an Australian undergraduate nursing degree. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2018, 32, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Republic of Korea. A Policy Analysis on the Introduction of Accelerated Bachelor of Science in Nursing (ABSN) Program. 2024. Available online: https://www.mohw.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10411010100&bid=0019 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Mehr, K.E.; Daltry, R. Examining Mental Health Differences between Transfer and Nontransfer University Students Seeking Counseling Services. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 2016, 30, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghareeb, A.; McKenna, L.; Cooper, S. The Influence of Anxiety on Student Nurse Performance in a Simulated Clinical Setting: A Mixed Methods Design. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 98, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, H. Correlation Research on Psychological Health Impact on Nursing Students against Stress, Coping Way and Social Support. Nurse Educ. Today 2009, 29, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, D.L.; Sapp, A.; Baker, K.A. Belongingness in Undergraduate/Pre-Licensure Nursing Students in the Clinical Learning Environment: A Scoping Review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2022, 64, 103422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bledsoe, S.; Baskin, J.J.; Berry, F. Fear Not! How Students Cope with the Fears and Anxieties of College Life. Coll. Teach. 2018, 66, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, T.L.; Janiszewski Goodin, H. Nursing Student Anxiety as a Context for Teaching/Learning. J. Holist. Nurs. 2013, 31, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, M.; Mulroy, T.; Carver, M. Exploring Coping Strategies of Transfer Students Joining Universities from Colleges. Stud. Success 2020, 11, 1–81d. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, A.B. Transitional Challenges in a Two-plus-Two Nursing Program: Phenomenology of Student Experiences. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 54, 103139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgibbon, K.; Murphy, K.D. Coping Strategies of Healthcare Professional Students for Stress Incurred during Their Studies: A Literature Review. J. Ment. Health 2023, 32, 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charleston, R.; Happell, B. Coping with Uncertainty within the Preceptorship Experience: The Perceptions of Nursing Students. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2005, 12, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoudi Alavi, N. Self-Efficacy in Nursing Students. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2014, 3, e25881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tantillo, M.; Marconi, M.A.; Rideout, K.; Anson, E.A.; Reifenstein, K.A. Creating a Nursing Student Center for Academic and Professional Success. J. Nurs. Educ. 2017, 56, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.-K.; Chung, S.-K. Relationship among College Life Stress, Alienation and College Adjustment: Focused on Transferred and Non-Transferred Nursing Students. J. Korean Data Anal. Soc. 2015, 17, 2779–2793. [Google Scholar]

- Lewkonia, R. Educational Implications of Practice Isolation. Med. Educ. 2001, 35, 528–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celerio, J.G. Through the revolving door: Experiences of nursing students. Int. J. Res. Publ. 2022, 103, 951–960. [Google Scholar]

- Cederbaum, J.; Klusaritz, H.A. Clinical Instruction: Using the Strengths-Based Approach with Nursing Students. J. Nurs. Educ. 2009, 48, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oh, S.; Lee, K.; Mok, H.; Jo, K. Bridging the Gap: A Phenomenological Study of Transfer Students’ Journey into Professional Nursing. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15020072

Oh S, Lee K, Mok H, Jo K. Bridging the Gap: A Phenomenological Study of Transfer Students’ Journey into Professional Nursing. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(2):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15020072

Chicago/Turabian StyleOh, Seungeun, Kyunghwa Lee, Hyungkyun Mok, and Kyuhee Jo. 2025. "Bridging the Gap: A Phenomenological Study of Transfer Students’ Journey into Professional Nursing" Nursing Reports 15, no. 2: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15020072

APA StyleOh, S., Lee, K., Mok, H., & Jo, K. (2025). Bridging the Gap: A Phenomenological Study of Transfer Students’ Journey into Professional Nursing. Nursing Reports, 15(2), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15020072