Healthcare Professionals’ Interactions with Families of Hospitalized Patients Through Information Technologies: Toward the Integration of Artificial Intelligence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

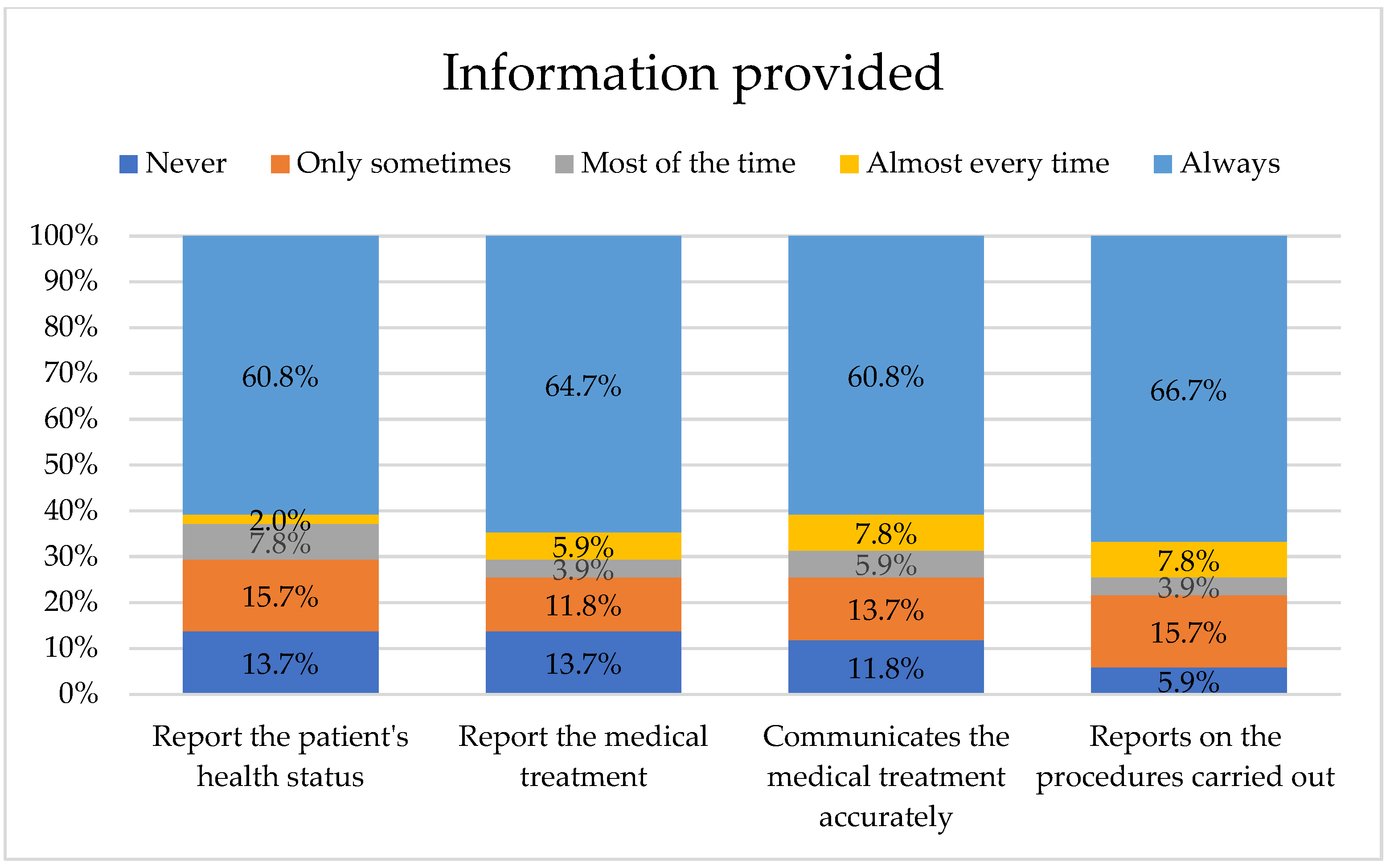

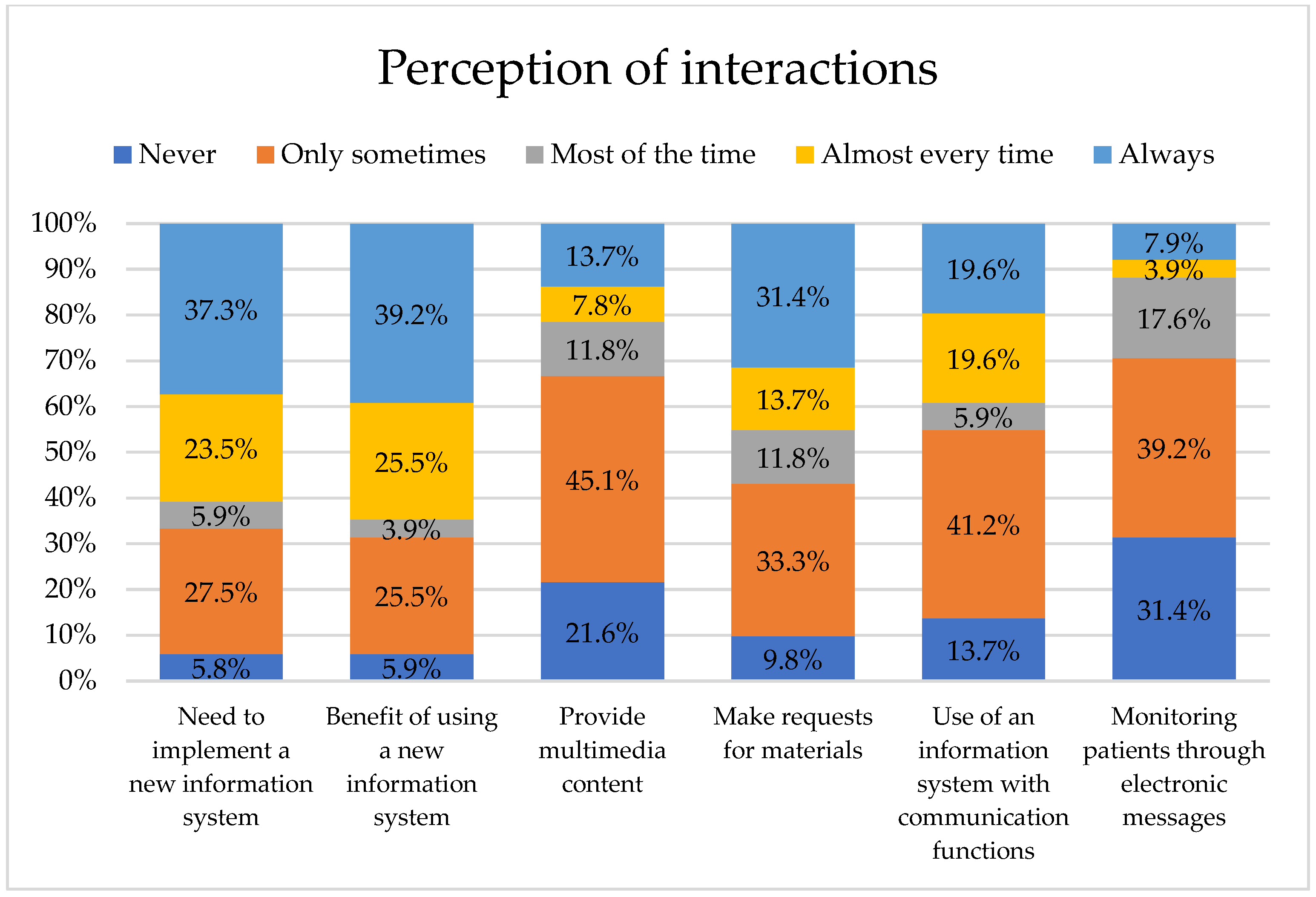

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Armoiry, X.; Sturt, J.; Phelps, E.E.; Walker, C.-L.; Court, R.; Taggart, F.; Sutcliffe, P.; Griffiths, F.; Atherton, H. Digital Clinical Communication for Families and Caregivers of Children or Young People With Short- or Long-Term Conditions: Rapid Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernild, C.; Missel, M.; Berg, S. COVID-19: Lessons Learned About Communication Between Family Members and Healthcare Professionals—A Qualitative Study on How Close Family Members of Patients Hospitalized in Intensive Care Unit With COVID-19 Experienced Communication and Collaboration With Healthcare Professionals. Inq. J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2021, 58, 00469580211060005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamer, T.; Steinhäuser, J.; Flägel, K. Artificial Intelligence Supporting the Training of Communication Skills in the Education of Health Care Professions: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e43311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, S.; Jeong, S.; Paeng, H.; Yoo, S.; Son, M.H. Communication challenges and experiences between parents and providers in South Korean paediatric emergency departments: A qualitative study to define AI-assisted communication agents. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e094748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.Y.; Tsai, H.H.; Shieh, W.Y.; Weng, L.C.; Huang, H.L.; Liu, C.Y. Expectations of AI-supported communication in nurse-family interactions in nursing homes: Navigating ambiguities in role transformation. Digit. Health 2025, 11, 20552076251362385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindberg, B.; Nilsson, C.; Zotterman, D.; Söderberg, S.; Skär, L. Using Information and Communication Technology in Home Care for Communication between Patients, Family Members, and Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Telemed. Appl. 2013, 2013, 461829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cermak, C.A.; Read, H.; Jeffs, L. Health Care Professionals’ Experiences With Using Information and Communication Technologies in Patient Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Qualitative Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e53056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrez-Ojeda, I.; Vanegas, E.; Felix, M.; Mata, V.L.; Jiménez, F.M.; Sanchez, M.; Simancas-Racines, D.; Cherrez, S.; Gavilanes, A.W.D.; Eschrich, J.; et al. Frequency of Use, Perceptions and Barriers of Information and Communication Technologies Among Latin American Physicians: An Ecuadorian Cross-Sectional Study. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2020, 13, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, A.; Neveditsin, N.; Tanveer, H.; Mago, V. Toward Fairness, Accountability, Transparency, and Ethics in AI for Social Media and Health Care: Scoping Review. JMIR Med. Inform. 2024, 12, e50048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denecke, K.; Lopez-Campos, G.; Rivera-Romero, O.; Gabarron, E. The Unexpected Harms of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Reflections on Four Real-World Cases. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2025, 325, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M. Ethical AI in medical text generation: Balancing innovation with privacy in public health. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1583507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Alrazaq, A.A.; Alajlani, M.; Ali, N.; Denecke, K.; Bewick, B.M.; Househ, M. Perceptions and Opinions of Patients About Mental Health Chatbots: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e17828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermansen, A.; Regier, D.A.; Pollard, S. Developing Data Sharing Models for Health Research with Real-World Data: A Scoping Review of Patient and Public Preferences. J. Med. Syst. 2022, 46, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiberta, P.; Boada, I.; Thió-Henestrosa, S.; Ortuño, P.; Pedraza, S. Introducing Online Continuing Education in Radiology for General Practitioners. J. Med. Syst. 2020, 44, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Li, T.C.; Chang, Y.W.; Liao, H.C.; Huang, H.M.; Huang, L.C. Exploring the relationships among professional quality of life, personal quality of life and resignation in the nursing profession. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 2689–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Jiao, D.; Liu, X.; Zhu, T. A Comparison of the Psycholinguistic Styles of Schizophrenia-Related Stigma and Depression-Related Stigma on Social Media: Content Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e16470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Alestedt, L.T.; Vaca Morales, S.M.; Martínez Changuan, D.I.; Suasnavas Bermúdez, P.R.; Cárdenas Moncayo, I.M.; Gómez García, A.R. Diseño y Validación de un Cuestionario para el Diagnóstico de Riesgos Psicosociales en Empresas Ecuatorianas. Cienc. Trab. 2018, 20, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunder, R.G.; Heeney, N.D.; Jeffs, L.P.; Wiesenfeld, L.A.; Hunter, J.J. A longitudinal study of hospital workers’ mental health from fall 2020 to the end of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2023. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguin-Fowler, R.A.; Demment, M.; Folta, S.C.; Graham, M.; Hanson, K.; Maddock, J.E.; Patterson, M.S. Recruiting experiences of NIH-funded principal investigators for community-based health behavior interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2023, 131, 107271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, J.A.; Reding-Bernal, A.; López-Alvarenga, J.C. Cálculo del tamaño de la muestra en investigación en educación médica. Investig. Educ. Médica 2013, 2, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Luna, J.F.; Armendáriz Mireles, E.N.; Nuño Maganda, M.A.; Herrera Rivas, H.; Machucho Cadena, R.; Hernández Almazán, J.A. Design and validation of a preliminary instrument to contextualize interactions through information technologies of health professionals. Health Inform. J. 2024, 30, 14604582241259323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M. Sample Size Determination for Survey Research and Non-Probability Sampling Techniques: A Review and Set of Recommendations. J. Entrep. Bus. Econ. 2023, 11, 42–62. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskin, C.J.; Happell, B. On exploratory factor analysis: A review of recent evidence, an assessment of current practice, and recommendations for future use. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harerimana, A.; Mtshali, N.G. Using Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis to understand the role of technology in nursing education. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 92, 104490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izquierdo, I.; Olea, J.; Abad, F.J. Exploratory factor analysis in validation studies: Uses and recommendations. Psicothema 2014, 26, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mundial, A.M. Declaración de Helsinki de la AMM-Principios éticos para las Investigaciones Médicas en Seres Humanos. Available online: https://www.wma.net/es/policies-post/declaracion-de-helsinki-de-la-amm-principios-eticos-para-las-investigaciones-medicas-en-seres-humanos/ (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- Chanchalani, G.; Arora, N.; Nasa, P.; Sodhi, K.; Bahrani, M.J.A.; Tayar, A.A.; Hashmi, M.; Jaiswal, V.; Kantor, S.; Lopa, A.J.; et al. Visiting and Communication Policy in Intensive Care Units during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-sectional Survey from South Asia and the Middle East. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 28, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, X.M.; Zimba, O.; Gupta, L. Informed Consent for Scholarly Articles during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2021, 36, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Allen, C. Enablers, barriers and strategies for adopting new technology in accounting. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2024, 52, 100666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzghaibi, H.; Hutchings, H. Exploring electronic health record systems implementation in primary health care centres in Saudi Arabia: Pre-post implementation. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1502184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwan, K.; Awoke, T.; Tilahun, B. Knowledge and Utilization of Computers Among Health Professionals in a Developing Country: A Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Hum. Factors 2015, 2, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swoboda, C.M.; Van Hulle, J.M.; McAlearney, A.S.; Huerta, T.R. Odds of talking to healthcare providers as the initial source of healthcare information: Updated cross-sectional results from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). BMC Fam. Pract. 2018, 19, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, N.K.; Adzakpah, G.; Kissi, J.; Abdulai, K.; Taylor-Abdulai, H.; Johnson, S.B.; Opoku, C.; Hallo, C.; Boadu, R.O. Health professionals’ perceptions of electronic health records system: A mixed method study in Ghana. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2024, 24, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges do Nascimento, I.J.; Abdulazeem, H.; Vasanthan, L.T.; Martinez, E.Z.; Zucoloto, M.L.; Østengaard, L.; Azzopardi-Muscat, N.; Zapata, T.; Novillo-Ortiz, D. Barriers and facilitators to utilizing digital health technologies by healthcare professionals. NPJ Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endalamaw, A.; Khatri, R.B.; Mengistu, T.S.; Erku, D.; Wolka, E.; Zewdie, A.; Assefa, Y. A scoping review of continuous quality improvement in healthcare system: Conceptualization, models and tools, barriers and facilitators, and impact. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurynski, Y.; Ludlow, K.; Testa, L.; Augustsson, H.; Herkes-Deane, J.; Hutchinson, K.; Lamprell, G.; McPherson, E.; Carrigan, A.; Ellis, L.A.; et al. Built to last? Barriers and facilitators of healthcare program sustainability: A systematic integrative review. Implement. Sci. 2023, 18, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldfarb, G.; Nasanovsky, J.; Krynski, L.; Ciancaglini, A.; García Bournissen, F. Use of information and communication technologies by argentine pediatricians. Arch. Argent. De Pediatr. 2019, 117, S264–S276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Globus, O.; Leibovitch, L.; Maayan-Metzger, A.; Schushan-Eisen, I.; Morag, I.; Mazkereth, R.; Glasser, S.; Kaplan, G.; Strauss, T. The use of short message services (SMS) to provide medical updating to parents in the NICU. J. Perinatol. Off. J. Calif. Perinat. Assoc. 2016, 36, 739–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcelik, H.; Erdogan, N. Relationship Between the Needs of Turkish Relatives of Patients Admitted to an Intensive Care Unit and Their Coping Styles. OMEGA-J. Death Dying 2022, 85, 990–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco Bueno, J.M.; Alonso-Ovies, A.; Heras La Calle, G.; Zaforteza Lallemand, C. Principales demandas informativas de los familiares de pacientes ingresados en Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos. Med. Intensiv. 2018, 42, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manias, E.; Bucknall, T.; Wickramasinghe, N.; Gray, K.; Schaffer, J.; Rosenfeld, E. Patient and family engagement in communicating with electronic medical records in hospitals: A systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2020, 134, 104036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegal, G.; Dagan, E.; Wolf, M.; Duvdevani, S.; Alon, E.E. Medical Information Exchange: Pattern of Global Mobile Messenger Usage among Otolaryngologists. Otolaryngol.–Head Neck Surg. 2016, 155, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciancaglini, A.; Nuñez, J.; Jaitt, M.; Otero, P.; Goldfarb, G. The electronic medical record in pediatrics: Functionalities and best use practices. Arch. Argent. Pediatr. 2021, 119, S236–S245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagno, S.; Khalifa, M. Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence Among Healthcare Staff: A Qualitative Survey Study. Front. Artif. Intell. 2020, 3, 578983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, R.; Fakieh, B. Health Care Employees’ Perceptions of the Use of Artificial Intelligence Applications: Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e17620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.I.; Madi, M.; Sopka, S.; Lenes, A.; Stange, H.; Buszello, C.-P.; Stephan, A. An integrative review on the acceptance of artificial intelligence among healthcare professionals in hospitals. NPJ Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namdar Areshtanab, H.; Rahmani, F.; Vahidi, M.; Saadati, S.Z.; Pourmahmood, A. Nurses perceptions and use of artificial intelligence in healthcare. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panteli, D.; Adib, K.; Buttigieg, S.; Goiana-da-Silva, F.; Ladewig, K.; Azzopardi-Muscat, N.; Figueras, J.; Novillo-Ortiz, D.; McKee, M. Artificial intelligence in public health: Promises, challenges, and an agenda for policy makers and public health institutions. Lancet Public Health 2025, 10, e428–e432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alowais, S.A.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Alsuhebany, N.; Alqahtani, T.; Alshaya, A.I.; Almohareb, S.N.; Aldairem, A.; Alrashed, M.; Bin Saleh, K.; Badreldin, H.A.; et al. Revolutionizing healthcare: The role of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faiyazuddin, M.; Rahman, S.J.Q.; Anand, G.; Siddiqui, R.K.; Mehta, R.; Khatib, M.N.; Gaidhane, S.; Zahiruddin, Q.S.; Hussain, A.; Sah, R. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Healthcare: A Comprehensive Review of Advancements in Diagnostics, Treatment, and Operational Efficiency. Health Sci. Rep. 2025, 8, e70312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, J.; Munir, U.; Nori, A.; Williams, B. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: Transforming the practice of medicine. Future Healthc. J. 2021, 8, e188–e194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, T.P.; Senadeera, M.; Jacobs, S.; Coghlan, S.; Le, V. Trust and medical AI: The challenges we face and the expertise needed to overcome them. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. JAMIA 2021, 28, 890–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Kang, J.; Chu, M.; Min, H.; Kim, S. Use of electronic medical records in simulated nursing education and its educational outcomes: A scoping review. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2025, 101, 101703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Berndtzon, M.; Nichitelea, D. “If You’ve Trained, Then It’s Much Easier”—Health Care Professionals’ Experiences of Participating in Simulation. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2024, 87, 101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Data | Value | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Man | 19 | 37.3% |

| Woman | 32 | 62.7% | |

| Total | 51 | 100.0% | |

| Age | From 18 to 29 years old | 6 | 11.8% |

| From 30 to 39 years old | 19 | 37.3% | |

| From 40 to 49 years old | 15 | 29.4% | |

| From 50 to 59 years old | 8 | 15.7% | |

| From 60 to 69 years old | 2 | 3.9% | |

| Over 69 years | 1 | 2.0% | |

| Total | 51 | 100.0% | |

| Place of residence | Rural | 2 | 3.9% |

| Urban | 49 | 96.1% | |

| Other | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Total | 51 | 100.0% | |

| Profession | Social worker | 0 | 0.0% |

| Nurse | 5 | 9.8% | |

| Specialist doctor | 19 | 37.3% | |

| Resident doctor | 10 | 19.6% | |

| Psychologist | 12 | 23.5% | |

| Nutritionist | 3 | 5.9% | |

| Dentist | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Other | 2 | 3.9% | |

| Total | 51 | 100.0% | |

| Area or department | Neonatal intensive care unit | 6 | 11.8% |

| Pediatric intensive care unit | 4 | 7.8% | |

| Hospitalization | 12 | 23.5% | |

| Emergency | 6 | 11.8% | |

| Surgery | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Oncology and hematology | 10 | 19.6% | |

| Administrative | 1 | 2.0% | |

| Other | 12 | 23.5% | |

| Total | 51 | 100.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lopez-Luna, J.-F.; Machucho, R.; Caballero-Rico, F.; Roque-Hernández, R.V.; Hernandez-Almazan, J.-A.; Herrera Rivas, H. Healthcare Professionals’ Interactions with Families of Hospitalized Patients Through Information Technologies: Toward the Integration of Artificial Intelligence. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120446

Lopez-Luna J-F, Machucho R, Caballero-Rico F, Roque-Hernández RV, Hernandez-Almazan J-A, Herrera Rivas H. Healthcare Professionals’ Interactions with Families of Hospitalized Patients Through Information Technologies: Toward the Integration of Artificial Intelligence. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(12):446. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120446

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopez-Luna, Jose-Fidencio, Ruben Machucho, Frida Caballero-Rico, Ramón Ventura Roque-Hernández, Jorge-Arturo Hernandez-Almazan, and Hiram Herrera Rivas. 2025. "Healthcare Professionals’ Interactions with Families of Hospitalized Patients Through Information Technologies: Toward the Integration of Artificial Intelligence" Nursing Reports 15, no. 12: 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120446

APA StyleLopez-Luna, J.-F., Machucho, R., Caballero-Rico, F., Roque-Hernández, R. V., Hernandez-Almazan, J.-A., & Herrera Rivas, H. (2025). Healthcare Professionals’ Interactions with Families of Hospitalized Patients Through Information Technologies: Toward the Integration of Artificial Intelligence. Nursing Reports, 15(12), 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120446