Barriers, Enablers, and Impacts of Implementing National Comprehensive Care Standards in Acute Care Hospitals: An Interview Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the barriers and enablers encountered by care professionals in acute care hospitals during the implementation of the CCS?

- What strategies can be used to improve the implementation of the CCS?

- What are the perceived impacts of CCS implementation on patients, staff, and the hospital?

2. Method

2.1. Design

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.3. Study Setting and Recruitment

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Data Collection

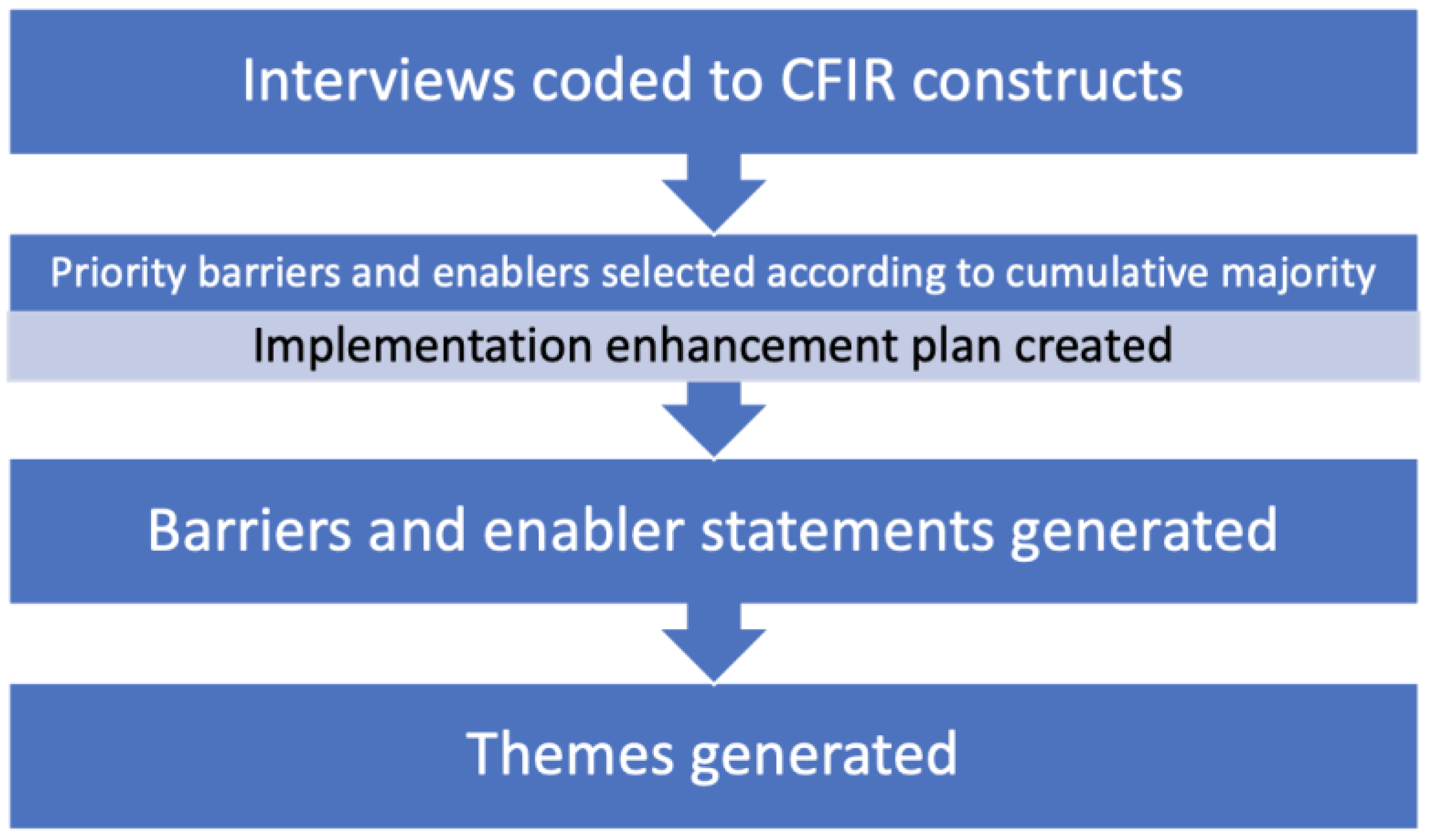

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Research Team and Reflexivity

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

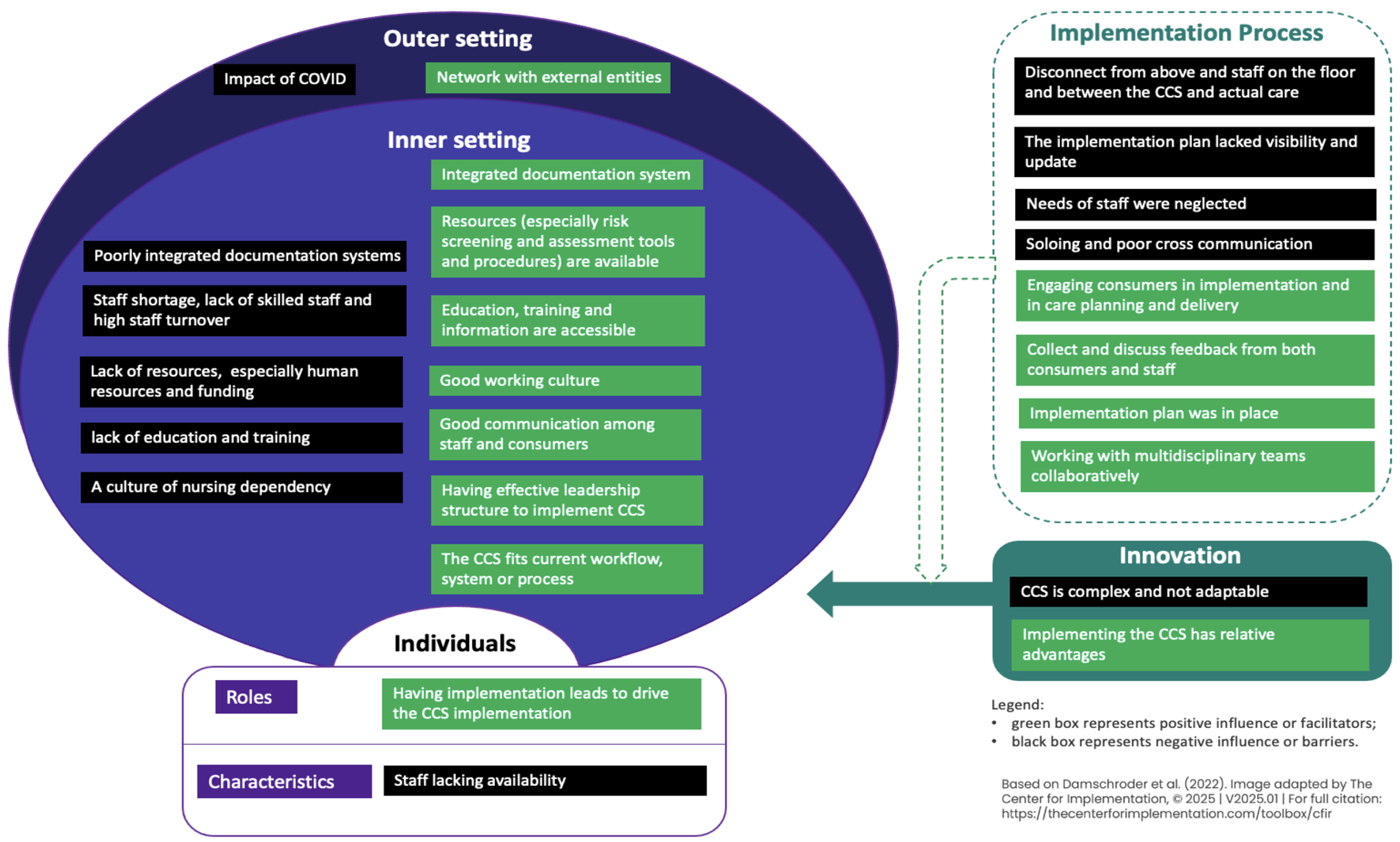

3.2. Barriers and Enablers

3.2.1. CFIR Domains and Barrier Constructs

3.2.2. CFIR Domains and Enabler Constructs

3.2.3. Themes of Barriers and Enablers

3.2.4. ERIC Strategy Mapping

3.3. Perceived Impacts

3.3.1. Perception of the Implementation

“I’m not confident at all in it, unfortunately. I’ve talked to a lot of nurses on the wards about it and the majority of us feel as though it was something that was actually unnecessary.”(F07, nurse, 3–10 years of work experience)

“I would say that we’re still in the tweaking stages. I feel like it’s not fully there. We feel like it’s progressing, but it’s not a complete product by any structure.”(F04, allied health, 3–10)

“I think we’re getting there, slowly. I think we’ve still got a bit of work to do. I’m hoping that if we continue to build with some of the strategies and the ideas that we will hopefully eventually get it right.”(F10, nurse, over 30)

“I think it will be implemented successfully. We’ve implemented a lot of things and they’ve all been done successfully. Well, they were liked by all the staff.”(F06, nurse, 11–20)

“I think if we truly embrace these standards and we’re looking at changing-- having these big system changes that we incorporate some of this stuff into those changes so that they are right from the start, it becomes a new way of working in a way.”(F10, nurse, over 30)

“I suspect a lot of that will have to do with experience as well because this is just my general vibe. I find the younger staff tend to say, ‘We don’t have enough resources.’ The staff that have a great deal more experience go, ‘Oh, we’ll just get on with it’.”(F15, nurse, over 30)

3.3.2. Perceived Impacts on Hospitals

“I think where things were already being done well and people were getting wide broad overviews, no [chuckles], different forms, different paperwork, different policies probably not a lot of different care.”(F03, doctor, 21–30)

“Timing of what happened when is always a little bit harder to recall.”(F03, doctor, 21–30)

“I don’t believe there are any direct costs incurred where the only costs incurred in these would be attributable to staff time, in their time from an auditing, education and supporting implementation perspective where it requires an update to forms, templates, etc. There is a time commitment and a printing cost where we change things … when you update audit tools, … there is a licensing cost … We have one at our hospital whose sole role is supporting the implementation of the comprehensive care standard. … there is one role that you have an attributed cost.”(M01, nurse, 21–30)

“I manage a cost centre and 15 staff, but I would say no tangible impacts to the cost centre that I manage, …, with new physicians who were brought on to help support the comprehensive care standard implementation. … That would’ve had a financial impact…”(F16, allied health, 3–10)

“We have a large comprehensive care admission document, and then we’re mainly responsible for completing that, doing a lot of the screening on admission and things like that. There are a few different assessments, a few more involved cognitive assessments than previously.”(F07, nurse, 3–10)

“New clinical forms clinical risk screening and assessment, care planning, lots of work happening in that space.”(F18, nurse, 11–20)

“Certainly yes [change in electronic systems], in terms of the templates within the patient electronic medical record…”(F04, allied health, 3–10)

“We had Medtask implemented probably here 18 months ago, which is more of a centralised electronic communication which definitely improved communication between particularly nurses and doctors.”(F07, nurse, 3–10)

“…a lot of statewide changes, so things being driven by the state to keep things uniform across all of Queensland. We’re talking about fall pathways, pressure injury pathways, … restrictive practices … probably more formalised referral processes. They have all changed since the standard.”(F18, nurse, 11–20)

“I think it felt like a lot of policy change, a lot of reviews of procedures, and potentially quite unit-specific for me without necessarily a lot of on-the-ground change. I think it’s got potential and there are processes and areas that certainly I think, that did get some change.”(F03, doctor, 21–30)

“There’s a little bit more focus on cognitive screening and documentation on admission. There are plans for us to review the admission data collection for patients when they arrive at the ward and how that can be streamlined a little bit more so that people aren’t being asked the same questions in three different forms and how that can be passed around teams a little bit better both for the patients and the staff.”(F03, doctor, 21–30)

“It is very much encouraged now that if there is a situation where a patient needs to be flowed out or needs any kind of higher care than sort of our average working day, any of that is to be encouraged to be highlighted so that staffing and backup services can be supported in a more connective manner.”(F01, nurse, 21–30)

“In terms of students, I think there has been a push to meet workforce demands to include medical students and students of nursing to be a representative of the workforce now, there is a big push for that. We have only implemented the student in nursing, assistant in the nursing category, which is now an endorsed changed position title—under the supervision of a registered enrolled nurse, and registered nurses.”(M04, nurse, over 30)

“Staff ratios have been the same and job descriptions have seemed to have changed significantly.”(F05, nurse, over 30)

3.3.3. Perceived Impacts on Patients

“I think there is generally improved access to services because there have been new services developed. There’s more of a focus towards the at-home, care at home, neuro-at-home models. I think those provide a really good bridge temporarily. That’s been a massive area for development throughout COVID-19”(F04, allied health, 3–10)

“I think that because they’re more open to looking outside the box, I guess, that they’re making more referrals and getting more things in place for the patients now rather than before.”(F06, nurse, 11–20)

“Probably in the more non-regional settings. Probably, yes [change in access to health services]. I don’t think it’s changed much regionally or even remotely.”(F09, nurse, 21–30)

“I think it is generally a more multidisciplinary approach in terms of preventing readmissions and getting the adequate supports in place, ready for home or discharge elsewhere. Yes, I think there’s more of a discussion based around it rather than clinicians deciding treatment and it being less siloed model”(F04, allied health, 3–10)

“In our service, there are multiple new models of MDT [multidisciplinary teams] clinics that are coming to fruition at the moment and likely as a result of the change in standards and the push from maybe higher up in the hospital to do so.”(F19, allied health, 11–20)

“I think it’s a little bit early to say. I would hope that there’s a reduction in the number of readmissions because of more comprehensive planning and holistic planning around a patient’s care.”(F04, allied health, 3–10)

“I think for us to be able to prevent and identify risk a lot sooner makes a big difference and having some good processes around care and end-of-life for people outside of palliative care I think has made a difference in recognising delirium as well has made life—This is purely anecdotal on my part, but I do think all of these standards improve patient outcomes.”(F05, nurse, over 30)

3.3.4. Perceived Impacts on Staff

“I definitely think that increased workload in terms of documentation has been a really big issue. It is still in a trial period, but as the trial period has progressed, these care plans have been neglected more and more from what I have seen in patients’ files.”(F07, nurse, 3–10)

“So there definitely is, I am seeing, increasing workload demand with the increased expectation to deliver, but no kind of resourcing to match that expectation in delivery. And then, definitely, there is staff fatigue and staff burnout with change expectations.”(F12, nurse, 21–30)

“With regards to the comprehensive care, there’s certainly more burden, as far as education and training on nursing staff and clinical staff to actually meet the comprehensive care, to be aware of all of the strategies and stuff that are put in place. I think that there is more of a burden on the nursing staff.”(F22, nurse, 21–30)

“The comprehensive care has changed some of their data collection for admissions and probably would have a little bit of impact on time requirements, particularly of nursing staff.”(F03, doctor, 21–30)

“I’m going to say no, but that’s just because that’s what we’re used to. I don’t know. 28 years in there or there’s—we’re at about 1021 changes. As nurses, we’re fairly adaptable to all of those sorts of things.”(F09, nurse, 21–30)

“When the patient arrives at the emergency, okay, I’m focusing on medical issues but also I will be looking at social issues, at mental health problems at other services or if they need any help in the community, so that by that Comprehensive Standards, … It does help a lot … that will guide me … The psychosocial medical, physical, psychosocial values, preferences. By understanding Comprehensive Care, you have all these in your mind when you talk to the patient …, making sure you’re ticking all the boxes.”(M05, nurse, 3–10)

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Barriers and Enablers

4.3. Perceived Impacts

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

4.5. Recommendations for Further Research

4.6. Implications for Policy and Practice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACSQHC | Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care |

| CCS | Comprehensive Care Standard |

| CFIR | Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research |

| CNC | Clinical Nurse Consultant |

| eQC | Evaluating Quality of Care |

| ERIC | Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change |

| ieMR | Integrated Electronic Medical Record |

| MDT | Multidisciplinary Team |

| NSQHS | National Safety and Quality Health Service |

| PREMs | Patient Reported Experience Measures |

References

- Van Den Ende, E.S.; Schouten, B.; Kremers, M.N.T.; Cooksley, T.; Subbe, C.P.; Weichert, I.; Van Galen, L.S.; Haak, H.R.; Kellett, J.; Alsma, J.; et al. Understanding what matters most to patients in acute care in seven countries, using the flash mob study design. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartgerink, J.M.; Cramm, J.M.; Bakker, T.; van Eijsden, A.M.; Mackenbach, J.P.; Nieboer, A.P. The importance of multidisciplinary teamwork and team climate for relational coordination among teams delivering care to older patients. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, H.M.; Pearson, M.; Sheaff, R.; Asthana, S.; Wheat, H.; Sugavanam, T.P.; Britten, N.; Valderas, J.; Bainbridge, M.; Witts, L.; et al. Collaborative action for person-centred coordinated care (P3C): An approach to support the development of a comprehensive system-wide solution to fragmented care. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2017, 15, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACSQHC. National Safety and Quality Health Sevice Standards, 2nd ed.; Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care: Sydney, Australia, 2021. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-05/national_safety_and_quality_health_service_nsqhs_standards_second_edition_-_updated_may_2021.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Xiong, B.; Stirling, C.; Bailey, D.; Martin-Khan, M. The origin, evolution, and definition of comprehensive care: A discussion paper. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, K.; Kennedy, K.; Fulton, A.; Guerin, M.; Uy, J.; Wiles, L.; Carroll, P. Does Comprehensive Care Lead to Improved Patients Outcomes in Acute Care Settings? An Evidence Check Rapid Review; Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care: Sydney, Australia, 2015; Available online: https://www.saxinstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Does-comprehensive-care-lead-to-improved-patient-outcomes-in-acute-care-settings.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Hopman, P.; de Bruin, S.R.; Forjaz, M.J.; Rodriguez-Blazquez, C.; Tonnara, G.; Lemmens, L.C.; Onder, G.; Baan, C.A.; Rijken, M. Effectiveness of comprehensive care programs for patients with multiple chronic conditions or frailty: A systematic literature review. Health Policy 2016, 120, 818–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazemore, A.; Petterson, S.; Peterson, L.E.; Phillips, R.L., Jr. More Comprehensive Care Among Family Physicians is Associated with Lower Costs and Fewer Hospitalizations. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 13, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, B.; Stirling, C.; Martin-Khan, M. The implementation and impacts of national standards for comprehensive care in acute care hospitals: An integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2023, 10, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACSQHC. Consumers and Accreditation. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/national-safety-and-quality-health-service-nsqhs-standards/assessment-nsqhs-standards/consumers-and-accreditation (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Xiong, B.; Stirling, C.; Bailey, D.X.; Martin-Khan, M. The implementation and impacts of the Comprehensive Care Standard in Australian acute care hospitals: A survey study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgo, M.; Dalli, A. Australian health service organisation assessment outcome data for the first 2 years of implementing the Comprehensive Care Standard. Aust. Health Rev. 2022, 46, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACSQHC. Comprehensive Care Standard: Review of Implementation; Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care: Sydney, Australia, 2022.

- Xiong, B.; Bailey, D.X.; Stirling, C.; Prudon, P.; Martin-Khan, M. Identification of implementation enhancement strategies for national comprehensive care standards using the CFIR-ERIC approach: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberai, T.; Laver, K.; Woodman, R.; Crotty, M.; Kerkhoffs, G.; Jaarsma, R. Does implementation of a tailored intervention increase adherence to a National Safety and Quality Standard? A study to improve delirium care. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2021, 33, mzab006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, B. Implementation of the Comprehensive Care Standard in Acute Care Hospitals in Australia: Strategies, Barriers and Enablers, and Impacts; The University of Queensland: Brisbane, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, L.; McCabe, C.; Keogh, B.; Brady, A.; McCann, M. An overview of the qualitative descriptive design within nursing research. J. Res. Nurs. 2020, 25, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarén, M.; Pölkki, T.; Kanste, O. The management of digital competence sharing in health care: A qualitative study of managers’ and professionals’ views. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024, 80, 2051–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltz, T.J.; Powell, B.J.; Fernández, M.E.; Abadie, B.; Damschroder, L.J. Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: Diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Reardon, C.M.; Widerquist, M.A.O.; Lowery, J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implement. Sci. 2022, 17, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, B.J.; Waltz, T.J.; Chinman, M.J.; Damschroder, L.J.; Smith, J.L.; Matthieu, M.M.; Proctor, E.K.; Kirchner, J.E. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CFIR Research Team. Interview Guide Tool. Available online: https://cfirguide.org/guide/app/#/ (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Lumivero. NVivo (Version 12). Available online: www.lumivero.com (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaforce, A.; Li, J.; Grujovski, M.; Parkinson, J.; Richards, P.; Fahy, M.; Good, N.; Jayasena, R. Creating an Implementation Enhancement Plan for a Digital Patient Fall Prevention Platform Using the CFIR-ERIC Approach: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V.; Hayfield, N. Thematic analysis. In Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2015; Volume 222, p. 248. [Google Scholar]

- The Centre for Implementation. Image adapted from “The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback” by Laura J. Damschroder, et al. Available online: https://thecenterforimplementation.com/toolbox/cfir (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Mthethwa, R. Critical dimensions for policy implementation. Afr. J. Public Aff. 2012, 5, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Azeem, M. The role of innovation simplicity in innovation adaptability in the era of digital revolution: Empirical evidence from Pakistani shoe manufacturing industry. Bus. Rev. Digit. Revolut. 2022, 2, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M.; Singhal, A.; Quinlan, M.M. Diffusion of innovations. In An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 432–448. [Google Scholar]

- Vagnani, G.; Volpe, L. Innovation attributes and managers’ decisions about the adoption of innovations in organizations: A meta-analytical review. Int. J. Innov. Stud. 2017, 1, 107–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flottorp, S.A.; Oxman, A.D.; Krause, J.; Musila, N.R.; Wensing, M.; Godycki-Cwirko, M.; Baker, R.; Eccles, M.P. A checklist for identifying determinants of practice: A systematic review and synthesis of frameworks and taxonomies of factors that prevent or enable improvements in healthcare professional practice. Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moullin, J.C.; Dickson, K.S.; Stadnick, N.A.; Rabin, B.; Aarons, G.A. Systematic review of the exploration, preparation, implementation, sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarons, G.A.; Hurlburt, M.; Horwitz, S.M. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 38, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, P.; Bernhardsson, S. Context matters in implementation science: A scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer, T.; Sinsky, C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Ann. Fam. Med. 2014, 12, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, K.; Persson Fischier, U. What Managers Find Important for Implementation of Innovations in the Healthcare Sector—Practice Through Six Management Perspectives. Int J Health Policy Manag 2022, 11, 2261–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedberg, M.W.; Chen, P.G.; Van Busum, K.R.; Aunon, F.; Pham, C.; Caloyeras, J.; Mattke, S.; Pitchforth, E.; Quigley, D.D.; Brook, R.H. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. Rand Health Q. 2014, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Boone, S.; Tan, L.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Sotile, W.; Satele, D.; West, C.P.; Sloan, J.; Oreskovich, M.R. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 1377–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | State | Location | Size | Profession | Position | Years in Current Position | Years of Work Experience | Having a Leadership Role | Role Regards the CCS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F01 | QLD | Rural | Small | Nurse | Senior registered nurse and midwife | 3 months | 21 to 30 | No | Care delivery |

| F02 | QLD | Regional | Small | Nurse | Senior nurse (maternity) | Less than 3 | 3 to 10 | Yes | Care delivery |

| F03 | QLD | Metro | Large | Doctor | Consultant physician/geriatrician | 11 to 20 | 21 to 30 | Yes | Both |

| F04 | VIC | Metro | Large | Allied health | Dietitian, team leader | Less than 3 | 3 to 10 | Yes | Care delivery |

| F05 | QLD | Metro | Large | Nurse | Nurse educator (cancer and palliative care) | 3 to 10 | Over 30 | Yes | Care delivery |

| F06 | NSW | Metro | Large | Nurse | Nursing manager (pediatrics) | 3 to 10 | 11 to 20 | Yes | Both |

| F07 | TAS | Regional | Large | Nurse | Junior nurse | 6 months | 3 to 10 | No | Care delivery |

| F08 | QLD | Metro | Large | Nurse | Nursing manager (palliative care) | 3 to 10 | Over 30 | Yes | Care delivery |

| F09 | NSW | Regional | Large | Nurse | Senior nurse, team leader (pediatrics) | 3 to 10 | 21 to 30 | Yes | Care delivery |

| F10 | NSW | Metro | Large | Nurse | Senior nurse (pediatrics, CNC) | 3 to 10 | Over 30 | Yes | Both |

| F11 | QLD | Regional | Small | Nurse | Senior nurse (quality and safety, CNC) | 3 to 10 | 11 to 20 | Yes | Implementation lead |

| F12 | QLD | Regional | Large | Nurse | Senior nurse (quality and safety, CNC) | 3 to 10 | 21 to 30 | Yes | Implementation lead |

| F13 | QLD | Metro | Large | Allied health | Recreation officer (rehab) | Less than 3 | Less than 3 | No | Care delivery |

| F14 | WA | Metro | Medium | Nurse | Senior nurse (pediatrics, cardiology liaison nurse, quality and safety) | Less than 3 | 11 to 20 | Yes | Both |

| F15 | QLD | Metro | Large | Nurse | Senior nurse—RADAR nurse navigator | 3 to 10 | Over 30 | Yes | Care delivery |

| F16 | QLD | Remote | Small | Allied health | Allied health manager | 3 to 10 | 3 to 10 | Yes | Both |

| F17 | TAS | Regional | Large | Nurse | Junior nurse (surgical and medical) | 3 months | Less than 3 | No | Care delivery |

| F18 | QLD | Regional | Medium | Nurse | Senior nurse (pediatrics, quality and safety) | Less than 3 | 11 to 20 | Yes | Both |

| F19 | QLD | Regional | Medium | Allied health | Allied health (podiatrist, outpatient) | 3 to 10 | 11 to 20 | No | Care delivery |

| F20 | QLD | Regional | Large | Nurse | Senior nurse (CNC) | 10 to 20 | Over 30 | Yes | Both |

| F21 | QLD | Metro | Large | Doctor | Doctor (pediatrist, outpatient) | 10 to 20 | 21 to 30 | No | Care delivery |

| F22 | QLD | Metro | Large | Nurse | Senior nurse (stoke rehab) | 10 to 20 | 21 to 30 | No | Care delivery |

| F23 | TAS | Regional | Large | Nurse | Senior nurse (ICU) | 3 to 10 | 3 to 10 | Yes | Both |

| M01 | QLD | Metro | Large | Nurse | Nursing manager | 3 to 10 | 21 to 30 | Yes | Implementation lead |

| M02 | NSW | Regional | Large | Allied health | Allied health (occupational therapist) | Less than 3 | 3 to 10 | No | Both |

| M03 | QLD | Remote | Small | Allied health | Allied health (physiotherapist) | Less than 3 | 11 to 20 | No | Care delivery |

| M04 | QLD | Regional | Medium | Nurse | Nursing manager | 3 to 10 | Over 30 | Yes | Implementation lead |

| M05 | TAS | Regional | Large | Nurse | Senior nurse (ED) | 3 to 10 | 3 to 10 | Yes | Care delivery |

| CFIR Domain | Constructs | Barrier Statement | Exemplar Quotes (ID, Role, Years of Work Experience) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation | Complexity n = 16 | CCS is broad, open to interpretation, hard to implement |

|

| Adaptability n = 6 | CCS doesn’t fit various hospital settings |

| |

| Outer setting | Critical incidents n = 11 | COVID-19 impact on health care system, staff, and consumers |

|

| Inner setting | Available resources n = 21 | Lack of resources, especially human resources |

|

| Structural characteristics n = 20

| Documentation system (electronic, paper-based, or mixed) is not integrated Understaffing, high staff turnover, lack of experienced/skilled staff |

| |

| Culture n = 11 | Implementation work is nursing-focused and -dependent |

| |

| Access to knowledge & information n = 5 | Lack of education and training |

| |

| Individual | Opportunity n = 18 | Lack of availability |

|

| Implementation | Doing n = 13 | Disconnect from above and staff on the floor Disconnect between the CCS and actual care |

|

| Planning n = 12 | The implementation plan lacked visibility and updates |

| |

| Assessing needs n = 6 | Needs of staff were neglected |

| |

| Teaming n = 6 | Soloing and poor cross communication |

|

| CFIR Domain | Construct | Enabler Statement | Exemplar Quote (ID, Role, Years of Work Experience) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation | Relative Advantage n = 8 | Implementing CCS is better than current practice |

|

| Outer setting | Partnerships & Connections n = 17 | Hospital is networked with external entities |

|

| Inner setting | Access to knowledge & information n = 23 | Education, training and information are assessable |

|

| Structural characteristics n = 19

| Integrated documentation system and use of telehealth Having effective leadership structure to implement CCS |

| |

| Available resources n = 19 | Resources are available, e.g., risk screening and assessment tools and protocols |

| |

| Communication n = 9 | Good communication among staff and consumers, e.g., MDT meeting that involves consumer |

| |

| Compatibility n = 7 | The CCS fits current workflow, system or processes |

| |

| Culture n = 6 | Good working culture, supportive and encouraging, sharing knowledge, person-centred |

| |

| Individual | Implementation leads n = 19 | Having implementation leads that drive the CCS implementation |

|

| Implementation | Engaging Innovation recipients n = 22 | Engaging consumers in implementation and in care planning and delivery |

|

| Reflecting & evaluating Implementation n = 21 | Collect and discuss feedback from both consumer and staff |

| |

| Planning n = 14 | Implementation plan was in place |

| |

| Teaming n = 10 | Working with multidisciplinary teams collaboratively |

|

| CFIR Construct | Barrier | Enabler | ERIC Strategy (Most Strongly Recommended) | % of Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complexity | √ | Develop a formal implementation blueprint Promote adaptability | 43 40 | |

| Adaptability | √ | Promote adaptability | 73 | |

| Assessing needs | √ | Obtain and use staff feedback Involve staff | 76 71 | |

| Structural characteristics | √ | √ | Assess for readiness and identify barriers and facilitators | 36 |

| Available resources | √ | √ | Access new funding | 78 |

| Access to knowledge & information | √ | √ | Conduct educational meeting | 79 |

| Culture | √ | √ | Identify and prepare champions | 52 |

| Doing | √ | √ | Purposely reexamine the implementation | 45 |

| Planning | √ | √ | Develop a formal implementation blueprint | 73 |

| Reflecting & evaluating implementation | √ | Develop and implement tools for quality monitoring Audit and provide feedback | 60 56 | |

| Implementation leads | √ | Identify and prepare champions | 64 | |

| Engaging Innovation recipients | √ | Involve patients and family members | 59 | |

| Communication | √ | Promote network weaving Organise clinician implementation team meetings | 57 52 | |

| Relative Advantage | √ | Identify and prepare champions | 45 | |

| Partnerships & Connections | √ | Build a coalition | 62 | |

| Compatibility | √ | Promote adaptability Conduct local consensus discussions | 45 41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiong, B.; Bailey, D.X.; Stirling, C.; Prudon, P.; Martin-Khan, M. Barriers, Enablers, and Impacts of Implementing National Comprehensive Care Standards in Acute Care Hospitals: An Interview Study. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 428. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120428

Xiong B, Bailey DX, Stirling C, Prudon P, Martin-Khan M. Barriers, Enablers, and Impacts of Implementing National Comprehensive Care Standards in Acute Care Hospitals: An Interview Study. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(12):428. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120428

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiong, Beibei, Daniel X. Bailey, Christine Stirling, Paul Prudon, and Melinda Martin-Khan. 2025. "Barriers, Enablers, and Impacts of Implementing National Comprehensive Care Standards in Acute Care Hospitals: An Interview Study" Nursing Reports 15, no. 12: 428. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120428

APA StyleXiong, B., Bailey, D. X., Stirling, C., Prudon, P., & Martin-Khan, M. (2025). Barriers, Enablers, and Impacts of Implementing National Comprehensive Care Standards in Acute Care Hospitals: An Interview Study. Nursing Reports, 15(12), 428. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120428