A Global Overview of Missed Nursing Care During Care of In-Patients with Cancer: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

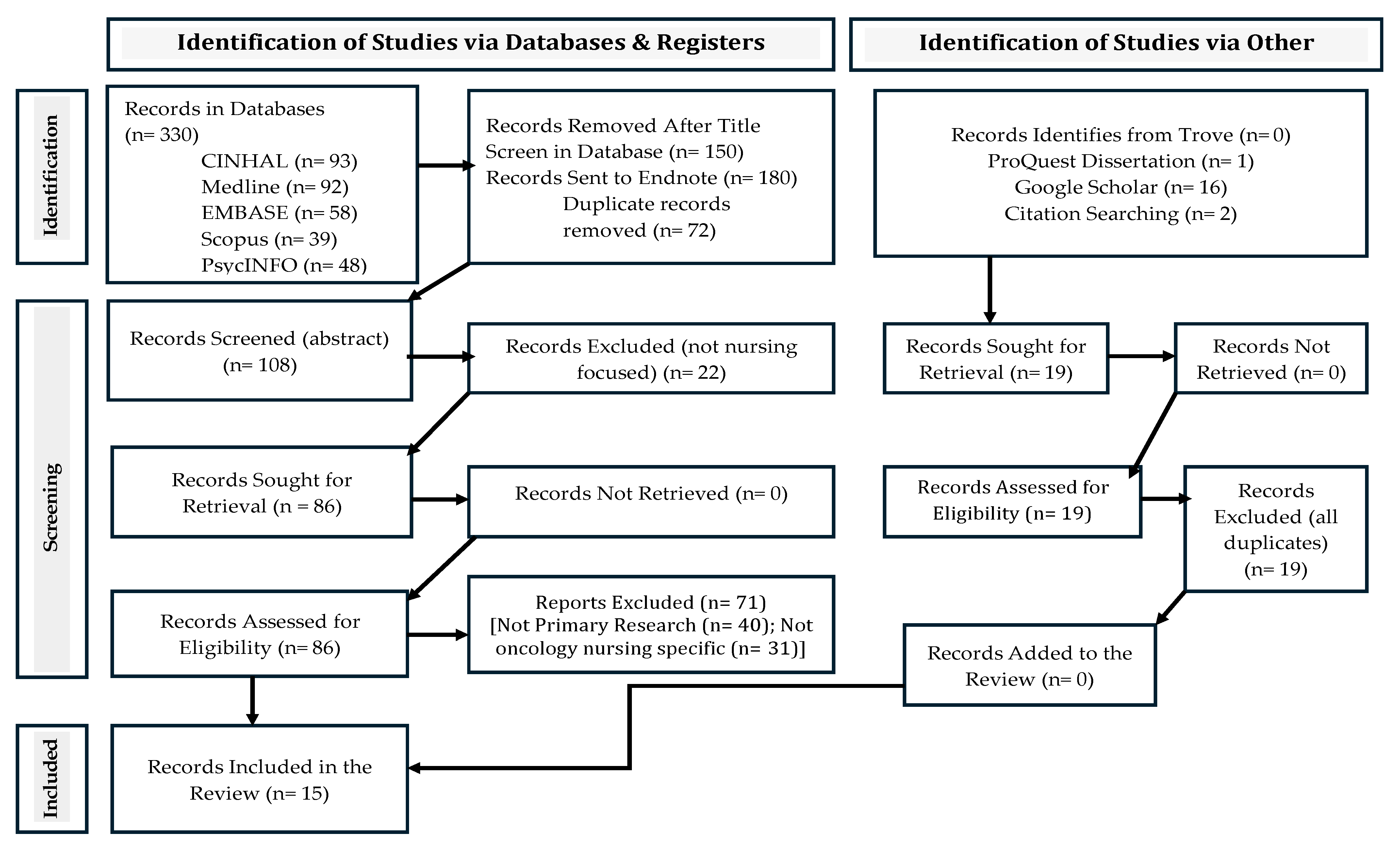

2. Methods

2.1. Identifying the Research Question

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

2.3. Selecting Studies

2.4. Charting the Data

2.5. Collating and Summarizing Data

| Authors | Country | Study Design | Setting | Participants | MNC Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albelbeisi et al. [23] | Palestine | Descriptive cross-sectional | Hospital-pediatric oncology wards | 52 Nurses | MNC questionnaire developed by authors (α = not reported) |

| Dehgha-Nayeri et al. [24] | Iran | Inductive qualitative content analysis | Oncology units of hospitals | 20 Nurse managers | Face-to-face interviews and focus group discussions using the interview guide |

| Friese et al. [25] | USA | Secondary analysis of survey data | Medical-surgical Units of 9 Hospitals in Midwestern states. | 352 Nurses | MISSCARE survey (Test–retest coefficient = 0.87) |

| Jankowska-Polańska et al. [26] | Poland | Descriptive cross-sectional | Department of Pediatric Oncology, Hematology, and Bone Marrow Transplant in a university hospital | 95 Nurses | BERNCA-R questionnaire (α = not reported) |

| Paiva et al. [27] | Portugal | Qualitative Descriptive | Inpatient units of an Oncology institution | 10 Nurses | Semi-structured interview guide |

| Paiva et al. [28] | Portugal | Qualitative Descriptive | Inpatient units of an Oncology institution | 10 Nurses | Semi-structured interview guide |

| Paiva et al. [29] | Portugal | Descriptive cross-sectional | Hospitals’ inpatient units exclusive for adult cancer patients | 298 Nurses | MISSCARE survey Portuguese version (Overall scale α = 0.86) |

| Pan & Lin [30] | Taiwan | Descriptive cross-sectional | Private specialty cancer hospital (oncology wards) | 111 Nurses | MISSCARE survey (Overall scale α = 0.90) |

| Papastavrou et al. [31] | Cyprus | Descriptive cross-sectional | Oncology-hematology units | 157 Nurses | MISSCARE survey (Part A α = 0.957, part B α = 0.936) |

| Piotrowska et al. [32] | Poland | Descriptive cross-sectional | The oncology department of the hospital | 100 Nurses | BERNCA-R questionnaire (α = not reported) |

| Rabin et al. [33] | Brazil | Descriptive cross-sectional | Inpatient oncology units of a private hospital | 83 Nurses | MISSCARE survey (α = 0.927) |

| Shamsi et al. [34] | Iran | Descriptive cross-sectional | Oncology wards of multiple hospitals | 93 Nurses | MISSCARE survey Persian version (α = not reported) |

| Villamin et al. [35] | USA | Descriptive, design | Six units of magnet-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers | 286 Nurses | MISSCARE survey (α = not reported) |

| Vryonides et al. [36] | Cyprus | Descriptive cross-sectional | Oncology-hematology units | 157 Nurses | MISSCARE survey (Overall scale α = 0.90) |

| Ying et al. [37] | China | Multi Center Descriptive cross-sectional | Oncology hospitals in six provinces | 446 Neuro-Oncology Nurses | Oncology Missed Nursing Care Self-Rating Scale (Overall scale α = 0.95) |

| Authors | Country | Most Frequently Missed Care Element | Most Perceived Reasons for Missed Care | Factors Associated with Missed Nursing Care and Other Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albelbeisi et al. [23] | Palestine |

|

|

|

| Dehgha-Nayeri et al. [24] | Iran |

|

|

|

| Friese et al. [25] | USA |

|

|

|

| Jankowska-Polańska et al. [26] | Poland |

|

|

|

| Paiva et al. [27] | Portugal |

|

|

|

| Paiva et al. [28] | Portugal |

|

|

|

| Paiva et al. [29] | Portugal |

|

|

|

| Pan & Lin [30] | Taiwan |

|

|

|

| Papastavrou et al. [31] | Cyprus |

|

|

|

| Piotrowska et al. [32] | Poland |

|

|

|

| Rabin et al. [33] | Brazil |

|

|

|

| Shamsi et al. [34] | Iran |

|

|

|

| Villamin et al. [35] | USA |

|

|

|

| Vryonides et al. [36] | Cyprus |

|

|

|

| Ying et al. [37] | China |

|

|

|

| Sub-Themes | Source/Citation |

|---|---|

| Medication administration | [23,25,26,28,30,32,33,36] |

| Proper documentation of nursing care | [23,25,26,27,30,36,37] |

| Assisting the patients with ambulation | [23,25,28,29,33,35,36] |

| Feeding or oral hydration | [23,25,27,28,34,36] |

| Oral hygiene | [23,25,27,28,35,36] |

| Positioning or turning of the patient | [23,25,28,33,35,36] |

| Proper patient assessment | [23,25,26,27,28,36,37] |

| Communication with patients and family | [23,26,27,28] |

| Attend multidisciplinary rounds & patient care conferences | [25,29,34,35,36] |

| Emotional and psychological support | [26,27,34,36] |

| Patient and family education | [23,25,28,36] |

| Proper discharge process | [23,32,36] |

| Toileting needs | [33,34,36] |

| Body hygiene | [23,28,35] |

| Hand hygiene | [26,30] |

| Monitoring vital signs | [28] |

| Laboratory testing | [28] |

| Patient supervision and monitoring | [26] |

| Activation of ordered or planned referrals | [32] |

| Clean the patient room and the patient care environment | [23] |

| Intake and output | [25] |

| Sub-Themes | Source/Citation |

|---|---|

| Workload | [24,27,28,29,30,31,33,34] |

| Staff nurse shortage | [23,24,27,29,30,31,33,34] |

| Inadequate number and training of support staff | [23,27,28,29,31,33,34] |

| Unexpected rise in patient load | [24,27,29,30,31,33,34] |

| Urgent and emergent patient conditions | [27,29,30,31,34] |

| Nurses’ lack of skills related to technology | [24,27,28,34] |

| Poor communication among health professionals | [27,29,31,33] |

| Lack of teamwork | [27,31,33,34] |

| Presence of visitors or absence of family caregiver | [24,30,33] |

| Inappropriate delegation | [24,27,33] |

| Lack of supplies and equipment | [24,27,33] |

| Patient health illiteracy | [24,27,28] |

| Lack of organizational support for innovation | [27,33,34] |

| Lack of patient safety culture | [23,24,29] |

| Poor recordkeeping and documentation | [24,28,34] |

| Lack of motivation and recognition | [23,26,28] |

| Nurses’ beliefs and attitudes | [27,28] |

| Negligence | [27,28] |

| Inexperienced nurses | [23,24] |

| Delays due to inaction by other healthcare providers | [24,30] |

| Complexity of care | [27] |

| Physical and emotional exhaustion of the nurse | [27] |

| Structural limitations of the unit/layout | [27] |

| Lack of continuing education | [23] |

| Patient culture and beliefs | [24] |

| Sub-Themes | Source/Citation |

|---|---|

| Job satisfaction | [29,31,32,37] |

| Unexpected increase in patient load | [25,26] |

| Perceived staff adequacy | [25,27] |

| Age of the nurse | [29,37] |

| Nurses’ formal education | [25,37] |

| Ethical climate in the unit | [36,37] |

| Emotional exhaustion and burnout | [32,37] |

| Lack of teamwork | [24] |

| Poor relationship with the managers | [24] |

| Lack of professionalism- nurse | [24] |

| Fatigue | [26] |

| Acuity of patient condition | [28] |

| Working overtime | [29] |

| Personality traits | [29] |

| Inefficient managers | [24] |

| Intuitive and analytical style of decision making | [29] |

| Intention to resign | [30] |

| Communication climate | [30] |

| Nurses experience | [30] |

3. Results

3.1. Common Missed Nursing Care

3.2. Reasons for Missed Nursing Care

3.3. Factors Associated with Missed Nursing Care

4. Discussion

4.1. Relevance to Clinical Practice

4.2. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kalisch, B.J.; Landstrom, G.L.; Hinshaw, A.S. Missed nursing care: A concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 509–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K.D.C.; Carvalho, D.E.; Lima, J.C.D.; Souza, L.A.; Silva, A.E.B.d.C. Factors associated with care omission and patient safety climate. Rev. Gaucha Enferm. 2024, 45, e20230059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, S.; Khankeh, H.R.; Sharifi, A.; Mohammadian, B. Missed nursing care: Concept analysis using the hybrid model. Res. Sq. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safety, W.P.; World Health Organization. Conceptual Framework for the International Classification for Patient Safety Version 1.1: Final Technical Report, January 2009; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Janatolmakan, M.; Khatony, A. Explaining the consequences of missed nursing care from the perspective of nurses: A qualitative descriptive study in Iran. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantsupawat, A.; Poghosyan, L.; Wichaikhum, O.A.; Kunaviktikul, W.; Fang, Y.; Kueakomoldej, S.; Thienthong, H.; Turale, S. Nurse staffing, missed care, quality of care, and adverse events: A cross-sectional study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recio-Saucedo, A.; Dall’Ora, C.; Maruotti, A.; Ball, J.; Briggs, J.; Meredith, P.; Redfern, O.C.; Kovacs, C.; Prytherch, D.; Smith, G.B.; et al. What impact does nursing care left undone have on patient outcomes? review of the literature. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 2248–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalisch, B.J.; Lee, K.H. Missed nursing care: Magnet versus non-Magnet hospitals. Nurs. Outlook 2012, 60, E32–E39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalisch, B.; Tschannen, D.; Lee, H. Does missed nursing care predict job satisfaction? J. Health Manag. 2011, 56, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, M.; Shashi, K.; Surabhi, M.; Shingade, N.; Kumar, V. The Global Perspective of Oncology Nursing and Its Challenges: Oncology Nursing and Its Challenges. WOCSI J. Med. Sci. 2024, 2, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Challinor, J.M.; Alqudimat, M.R.; Teixeira, T.O.; Oldenmenger, W.H. Oncology nursing workforce: Challenges, solutions, and future strategies. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, e564–e574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galassi, A.; Anwarali, S.; Challinor, J. Global challenges and initiatives in oncology nursing education. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2023, 12, 63345–63645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziarat, H.M.; Seyedfatemi, N.; Mardani-Hamooleh, M.; Farahani, M.A.; Vedadhir, A. Nursing in oncology ward with intertwined roles: A focused ethnography. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.A.I.; Asal, M.G.R.; Abdelaliem, S.M.F.; Alsenany, S.A.; Elsayed, B.K. The moderating role of just culture between nursing practice environment and oncology nurses’ silent behaviors toward patient safety: A multicentered study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 69, 102516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazqar, D.Y.; Attallah, D.M. Patient safety culture predictors and outcomes for sustainable oncology nursing practice: A cross-sectional correlational study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrague, L.J.; Kostovich, C.T. A global overview of missed nursing care during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2024, 46, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaboyer, W.; Harbeck, E.; Lee, B.O.; Grealish, L. Missed nursing care: An overview of reviews. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2020, 37, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; McKenzie, J.E.; Sowden, A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Brennan, S.E.; Ellis, S.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Ryan, R.; Shepperd, S.; Thomas, J.; et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: Reporting guideline. BMJ 2020, 368, l6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyes, J.; Lewin, S. Chapter 6: Supplemental guidance on selecting a method of qualitative evidence synthesis and integrating qualitative evidence with Cochrane intervention reviews. In Supplemental Guidance for Inclusion of Qualitative Research in Cochrane Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Noyes, J., Booth, A., Hannes, K., Harden, A., Harris, J., Lewin, S., Lockwood, C., Eds.; Version 1 (Updated August 2011); Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group: London, UK, 2011; Available online: http://cqrmg.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Albelbeisi, A.H.; Shaqfa, K.M.; Aiash, H.S.; Kishta, W.A.; Alreqeb, E.I. Prevalence of Missed Nursing Care and Associated Factors-a Nurse’s Perspective-at the Oncology Departments in Gaza Strip, Palestine. Austin J. Nurs. Health Care 2021, 8, 1062. [Google Scholar]

- Dehghan-Nayeri, N.; Shali, M.; Navabi, N.; Ghaffari, F. Perspectives of oncology unit nurse managers on missed nursing care: A qualitative study. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 5, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friese, C.R.; Kalisch, B.J.; Lee, K.H. Patterns and correlates of missed nursing care in inpatient oncology units. Cancer Nurs. 2013, 36, E51–E57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska-Polańska, B.; Czyrniańska, M.; Sarzyńska, K.; Świątoniowska-Lonc, N.; Chabowski, M. Impact of fatigue on nursing care rationing in paediatric haematology and oncology departments–a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, I.C.S.; Amaral, A.F.S.; Moreira, I.M.P.B. Missed nursing care in oncology: Exploring the problem of a Portuguese context. Rev. De Enferm. Ref. 2021, 5, e20138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, I.C.; Amaral, A.F.; Moreira, I.M. Missed nursing care: Perception of nurses from a Portuguese oncology hospital. Rev. De Enfermagen Ref. 2021, 5, e20075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, I.C.; Ventura, F.I.; Vilela, A.C.; Moreira, I.M. Influence of oncology nurses’ decision-making and personality traits on missed nursing care and related factors: A correlational study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2025, 74, 102749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.P.; Lin, C.F. The relationship between organizational communication and missed nursing care in oncology wards in Taiwan. Nurs. Open 2022, 9, 2750–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastavrou, E.; Charalambous, A.; Vryonides, S.; Eleftheriou, C.; Merkouris, A. To what extent are patients’ needs met on oncology units? The phenomenon of care rationing. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 21, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowska, A.; Lisowska, A.; Twardak, I.; Włostowska, K.; Uchmanowicz, I.; Mess, E. Determinants affecting the rationing of nursing care and professional burnout among oncology nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 7180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabin, E.G.; Silva, C.N.D.; Souza, A.B.D.; Lora, P.S.; Viegas, K. Application of the MISSCARE scale in an Oncology Service: A contribution to patient safety. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2019, 53, e03513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsi, A.; Dehghan, M.; Canillas-Dufau, T.; Forouzi, M.A. Cancer Care Unit Missed Care and Related Factors: View of Nurses of Southeastern Iran. MedSurg Nurs. 2023, 32, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamin, C.; Anderson, J.; Fellman, B.; Urbauer, D.; Brassil, K.P. Perceptions of missed care across oncology nursing specialty units. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2019, 4, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vryonides, S.; Papastavrou, E.; Charalambous, A.; Andreou, P.; Eleftheriou, C.; Merkouris, A. Ethical climate and missed nursing care in cancer care units. Nurs. Ethics 2018, 25, 707–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, L.; Yuyu, D.; Daili, Z.; Yangmei, S.; Qing, X.; Zhihuan, Z. Latent profile analysis of missed nursing care and their predictors among neuro-oncology nurses: A multicenter cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans Webb, M.; Murray, E.; Younger, Z.W.; Goodfellow, H.; Ross, J. The Supportive Care Needs of Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. J. Cancer Educ. 2021, 36, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donmez, E.; Dolu, I.; Dulger, Z.; Bayram, Z.; Can, G.; Akman, M. Care needs and satisfaction with nursing care quality of cancer patients. World Cancer Res. J. 2022, 9, e2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.M.; Charalambous, A.; Owen, R.I.; Njodzeka, B.; Oldenmenger, W.H.; Alqudimat, M.R.; So, W.K.W. Essential oncology nursing care along the cancer continuum. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, e555–e563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousoulou, M.; Suhonen, R.; Charalambous, A. Associations of individualized nursing care and quality oncology nursing care in patients diagnosed with cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 41, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putty, D.; Gungaphul, M.; Kassean, H. Factors Affecting the Quality of Nursing Care in an Oncology Setting—A Literature Review. J. Health Manag. 2024, 26, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Conceptual Framework for the International Classification for Patient Safety. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IER-PSP-2010.2 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). To Err Is Human: Building A Safer Health System; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; p. 9728. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Patient Safety Action Plan 2021–2030. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240032705 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- World Health Organization. Patient Safety. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/patient-safety (accessed on 13 November 2025).

| Keywords Search terms (all databases) MeSH or Thesaurus terms | Missed care, Missed nursing care, task undone, unfinished care, rationed care, care left undone, delayed care, nurse, nurses, cancer nurses, oncology nurses, oncologic care, chemotherapy, radiotherapy * OR nursing AND neoplasm N1 (missed care OR rationed care OR care left undone) Missed care (CINAHL, Medline, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Scopus); missed nursing care (CINAHL); Nurse, Oncology nursing (CINAHL, Medline); Nursing care, Nurse, Oncology Nurse (PsycINFO, Scopus) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muliira, J.K.; Lazarus, E.R.; Nandawula, P. A Global Overview of Missed Nursing Care During Care of In-Patients with Cancer: A Scoping Review. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120413

Muliira JK, Lazarus ER, Nandawula P. A Global Overview of Missed Nursing Care During Care of In-Patients with Cancer: A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(12):413. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120413

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuliira, Joshua Kanaabi, Eilean Rathinasamy Lazarus, and Prossy Nandawula. 2025. "A Global Overview of Missed Nursing Care During Care of In-Patients with Cancer: A Scoping Review" Nursing Reports 15, no. 12: 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120413

APA StyleMuliira, J. K., Lazarus, E. R., & Nandawula, P. (2025). A Global Overview of Missed Nursing Care During Care of In-Patients with Cancer: A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports, 15(12), 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120413