The Interplay of Disability, Depression, Social Support, and Quality of Life in Middle-Aged and Young Couples Affected by Stroke: A Dyadic Path Analysis Using the Actor–Partner Interdependence Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design

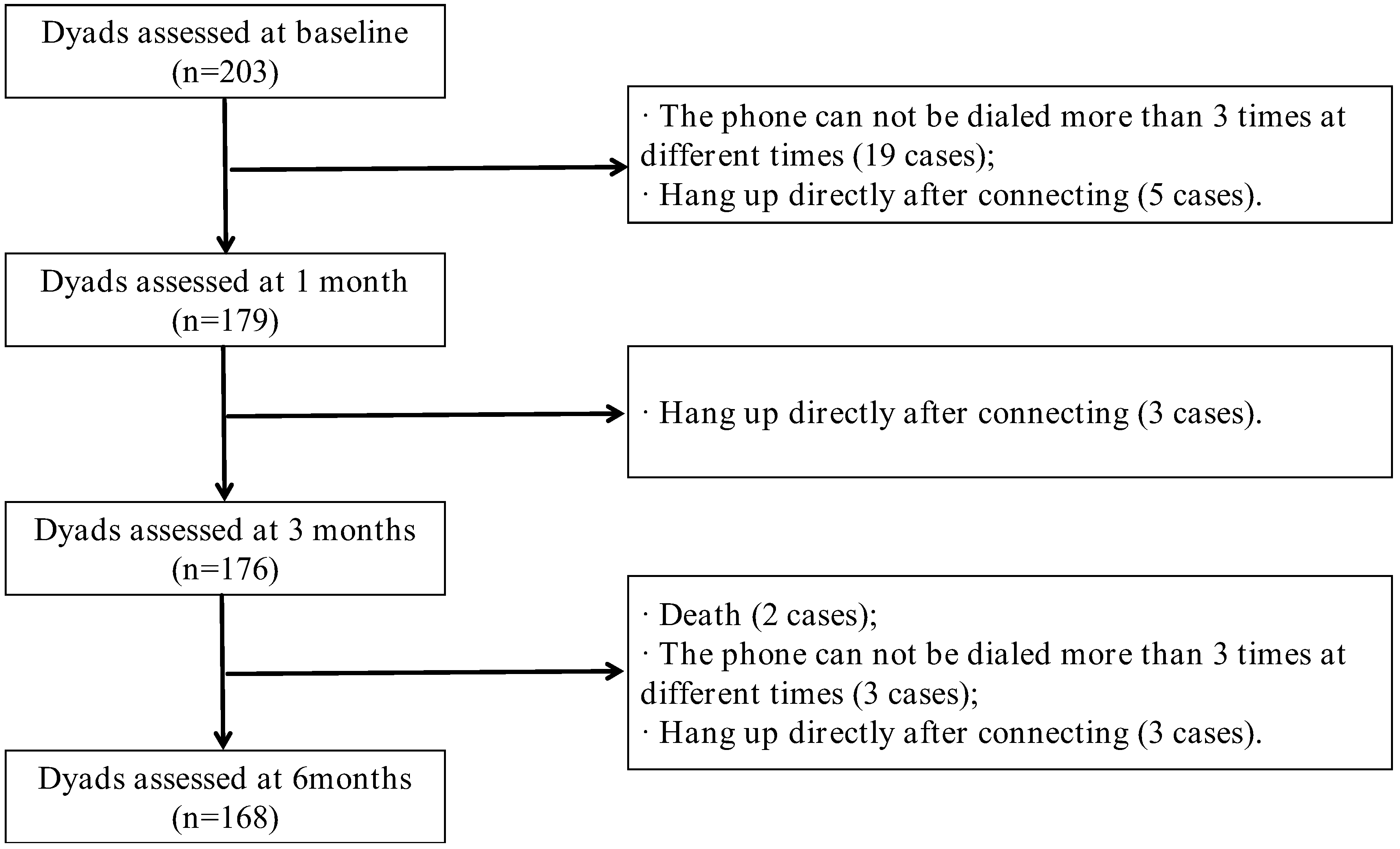

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure of Data Collection

2.4. Instruments

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Dyadic

3.2. Variable Scores and Trends over Time Among Stroke Survivor Couples

3.3. The Mediating Effect of Dyadic of Physical Health and Disability-Depression-Social Support in Couples of Stroke Survivors

3.4. The Mediating Effect of Dyadic Mental Health and Disability–Depression–Social Support in Couples of Stroke Survivors

4. Discussions

4.1. Effects of Disability on Dyadic Physical Health

4.2. Effects of Depression on Dyadic Physical Health

4.3. The Mediating Role of Social Support in the Relationship Between Disability and Dyadic Health

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- da Silva Etges, A.P.B.; Polanczyk, C.A.; Nabi, J. Revitalizing stroke care: The LEADER strategy for sustainable transformation in health care delivery. Stroke 2024, 55, e312–e315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekker, M.S.; Verhoeven, J.I.; Schellekens, M.; Boot, E.M.; van Alebeek, M.E.; Brouwers, P.; Arntz, R.M.; van Dijk, G.W.; Gons, R.; van Uden, I.; et al. Risk factors and causes of ischemic stroke in 1322 young adults. Stroke 2023, 54, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.S.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Barone, G.B.; Beaton, A.Z.; Boehme, A.K.; et al. 2024 heart disease and stroke statistics: A report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 149, e347–e913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; He, W.; Zhou, Y.; Mai, L.; Xu, L.; Li, C.; Li, M. Global burden of stroke in adolescents and young adults (aged 15–39 years) from 1990 to 2019: A comprehensive trend analysis based on the global burden of disease study 2019. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.J.; Wang, L.D.; Special Writing Group of China Stroke Surveillance Report. China stroke surveillance report 2021. Mil. Med. Res. 2023, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Kong, X.; Yang, C.; Cheng, Z.; Lv, J.; Guo, H.; Liu, X. Global, regional, and national burden of ischemic stroke, 1990–2021: An analysis of data from the global burden of disease study 2021. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 75, 102758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Wang, J.; Sun, W.; Liu, X. The advances of post-stroke depression: 2021 update. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 1236–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Sun, Q.; Guo, Y.; Yan, R.; Lv, Y. Mediation effect of perceived social support and resilience between physical disability and depression in acute stroke patients in China: A cross-sectional survey. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 308, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, M.A.; Ekker, M.S.; Allach, Y.; Cai, M.; Aarnio, K.; Arauz, A.; Arnold, M.; Bae, H.J.; Bandeo, L.; Barboza, M.A.; et al. Global differences in risk factors, etiology, and outcome of ischemic stroke in young adults: A worldwide meta-analysis, the GOAL initiative. Neurology 2022, 98, e573–e588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.X.; Xiang, D.D.; Zhang, Z.X.; Twumwaah, B.J.; Lin, B.L.; Chen, S.Y. Family function, self-efficacy, care hours per day, closeness and benefit finding among stroke caregivers in China: A moderated mediation model. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliana, S.; Yu, E.; Rias, Y.A.; Atikah, N.; Chang, H.J.; Tsai, H.T. Associations among disability, depression, anxiety, stress, and quality of life between stroke survivors and their family caregivers: An actor-partner interdependence model. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atteih, S.; Mellon, L.; Hall, P.; Brewer, L.; Horgan, F.; Williams, D.; Hickey, A. Implications of stroke for caregiver outcomes: Findings from the ASPIRE-S study. Int. J. Stroke 2015, 10, 918–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almhdawi, K.A.; Alazrai, A.; Kanaan, S.; Shyyab, A.A.; Oteir, A.O.; Mansour, Z.M.; Jaber, H. Post-stroke depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms and their associated factors: A cross-sectional study. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2021, 31, 1091–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xu, M.; Marshall, I.J.; Wolfe, C.D.; Wang, Y.; O’Connell, M.D. Prevalence and natural history of depression after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS Med. 2023, 20, e1004200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, J.A.; Burg, M.M.; Barefoot, J.; Williams, R.B.; Haney, T.; Zimet, G. Social support, type A behavior, and coronary artery disease. Psychosom. Med. 1987, 49, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, J.; Yang, L.; Lv, R.; Li, J.; Zhou, K.; Xu, M. The mediating effect of post-stroke depression between social support and quality of life among stroke survivors: A meta-analytic structural equation modeling. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2022, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villain, M.; Sibon, I.; Renou, P.; Poli, M.; Swendsen, J. Very early social support following mild stroke is associated with emotional and behavioral outcomes three months later. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maria, M.; Tagliabue, S.; Ausili, D.; Vellone, E.; Matarese, M. Perceived social support and health-related quality of life in older adults who have multiple chronic conditions and their caregivers: A dyadic analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 262, 113193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Tang, Y.; Zeng, P.; Guo, X.; Liu, Z. Psychological status on informal carers for stroke survivors at various phases: A cohort study in China. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1173062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.; Li, R.; Wang, L.; Yin, P.; Wang, Y.; Yan, C.; Ren, Y.; Qian, Z.; Vaughn, M.G.; McMillin, S.E.; et al. Temporal trend and attributable risk factors of stroke burden in China, 1990–2019: An analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, e897–e906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Shu, Y.; Han, C.; Liu, J. Correlation between family functioning and health beliefs in patients with stroke in Beijing, China. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2023, 16, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Mårtensson, J.; Zhao, Y.; Johansson, L. Living on the edge: Family caregivers’ experiences of caring for post-stroke family members in China: A qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 94, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.M. The Corbin and Strauss chronic illness trajectory model: An update. Sch. Inq. Nurs. Pract. 1998, 12, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kirkevold, M. The unfolding illness trajectory of stroke. Disabil. Rehabil. 2002, 24, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, K.S.; Lee, C.S. The theory of dyadic illness management. J. Fam. Nurs. 2018, 24, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evraire, L.E.; Dozois, D.J.A. An integrative model of excessive reassurance seeking and negative feedback seeking in the development and maintenance of depression. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 1291–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, V.F.; Dorstyn, D.S.; Taylor, A.M. The protective role of social support sources and types against depression in caregivers: A meta-analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 1304–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wu, B.; Gao, X.; Zhong, R. Association between frailty and cognitive function in older Chinese people: A moderated mediation of social relationships and depressive symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 316, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledermann, T.; Rudaz, M.; Wu, Q.; Cui, M. Determine power and sample size for the simple and mediation actor–partner interdependence model. Fam. Relat. 2022, 71, 1452–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, T.J.; Dawson, J.; Walters, M.R.; Lees, K.R. Reliability of the modified Rankin scale: A systematic review. Stroke 2009, 40, 3393–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, T.; Shi, Y.Z.; Zhang, N.; Zhu, M.F.; Li, J.J.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.X. Reliability and validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) in stroke patients with depression. Beijing Med. J. 2013, 35, 352–356. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, L.R.; Cao, H.Y.; Liao, M.X. Reliability Study of the 12-Item Brief Health Status Questionnaire for stroke survivors. Chin. J. Rehabil. Med. 2016, 31, 327–329. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, J.J.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolgeo, T.; De Maria, M.; Vellone, E.; Ambrosca, R.; Simeone, S.; Alvaro, R.; Pucciarelli, G. The association of spirituality with anxiety and depression in stroke survivor-caregiver dyads: An actor-partner interdependence model. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2022, 37, E97–E106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, V.A.; Tirschwell, D.L.; Becker, K.J.; Schubert, G.B.; Longstreth, W.J.; Creutzfeldt, C.J. Associations between measures of disability and quality of life at three months after stroke. J. Palliat. Med. 2024, 27, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuluunbaatar, E.; Chou, Y.J.; Pu, C. Quality of life of stroke survivors and their informal caregivers: A prospective study. Disabil. Health J. 2016, 9, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pont, W.; Groeneveld, I.; Arwert, H.; Meesters, J.; Mishre, R.R.; Vliet Vlieland, T.; Goossens, P. Caregiver burden after stroke: Changes over time? Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pădureanu, V.; Albu, C.V.; Caragea, D.C.; Bugă, A.M.; Florescu, M.M.; Pădureanu, R.; Biciușcă, V.; Sub Irelu, M.S.; Turcu-Știolică, A. Quality of life three months post-stroke among stroke patients and their caregivers in a single center study from Romania during the COVID-19 pandemic: A prospective study. Biomed. Rep. 2023, 19, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.H.; Song, X.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Kwok, T. Longitudinal analysis of quality of life for stroke survivors using latent curve models. Stroke 2008, 39, 2795–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhuang, K.; Fan, L.; Hua, Y.; Ni, C. Perceived stress, social support, and insomnia in hemodialysis patients and their family caregivers: An actor-partner interdependence mediation model analysis. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1172350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, D.M.; Huang, L.L.; Dou, J.; Wang, X.X.; Wang, P.X. Post-stroke depression as a predictor of caregivers’ burden of acute ischemic stroke patients in China. Psychol. Health Med. 2018, 23, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoli, D.; Brugnera, A.; Grego, A.; Alvaro, R.; Vellone, E.; Pucciarelli, G. Stroke disease-specific quality of life trajectories and their associations with caregivers’ anxiety, depression, and burden in stroke population: A longitudinal, multicentre study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2024, 23, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

path significant,

path significant,  path not significant.

path not significant.

path significant,

path significant,  path not significant.

path not significant.

path significant,

path significant,  path not significant.

path not significant.

path significant,

path significant,  path not significant.

path not significant.

| Characteristic | Follow-Up (N = 168) | Drop-Out (N = 35) | Statistic | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke Survivors | |||||

| Age ( ± s) | 51.32 ± 6.90 | 50.94 ± 7.11 | 0.289 | 0.773 c | |

| Gender | 0.038 | >0.999 a | |||

| Male | 127 (75.6) | 27 (77.1) | |||

| Female | 41 (24.4) | 8 (22.9) | |||

| Education | 0.180 | 0.945 a | |||

| Primary school | 43 (25.6) | 10 (28.6) | |||

| Middle school | 68 (40.5) | 13 (37.1) | |||

| High school | 57 (33.9) | 12 (34.3) | |||

| Monthly income (Yuan) | 0.447 | 0.843 a | |||

| <3000 | 65 (38.7) | 12 (34.3) | |||

| 3000~5000 | 59 (35.1) | 12 (34.3) | |||

| >5000 | 44 (26.2) | 11 (31.4) | |||

| Occupation before illness | - | 0.309 b | |||

| Farmer | 46 (27.4) | 7 (20.0) | |||

| Worker | 45 (26.8) | 15 (42.9) | |||

| Technical staff | 31 (18.5) | 8 (22.9) | |||

| Merchant | 23 (13.7) | 2 (5.7) | |||

| others | 17 (10.5) | 3 (8.6) | |||

| Medical payment form | - | 0.391 b | |||

| Employee health insurance | 42 (25.0) | 12 (34.3) | |||

| Resident medical insurance | 115 (68.5) | 20 (57.1) | |||

| others | 11 (6.5) | 3 (8.6) | |||

| Family the main economic pillar | 0.035 | >0.999 a | |||

| Yes | 132 (78.6) | 27 (77.1) | |||

| No | 36 (21.4) | 8 (22.9) | |||

| Stroke type | - | 0.814 b | |||

| hemorrhagic | 12 (7.1) | 3 (8.6) | |||

| ischemic | 154 (91.7) | 32 (91.4) | |||

| Mixed type | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Number of complications | 0.236 | 0.669 a | |||

| None | 40 (23.8) | 7 (20.0) | |||

| 1 or more kinds | 128 (76.2) | 28 (80.0) | |||

| Main symptom | 0.571 | 0.538 a | |||

| Limb dysfunction | 119 (70.8) | 27 (77.1) | |||

| others | 49 (29.2) | 8 (22.9) | |||

| Caregivers | |||||

| Age ( ± s) | 50.77 ± 7.38 | 51.29 ± 6.99 | −0.381 | 0.704 c | |

| Gender | 0.038 | >0.999 a | |||

| Male | 41 (24.4) | 8 (22.9) | |||

| Female | 127 (75.6) | 27 (77.1) | |||

| Education | 5.691 | 0.065 a | |||

| Primary school | 47 (28.0) | 17 (48.6) | |||

| Middle school | 74 (44.0) | 11 (31.4) | |||

| High school | 47 (28.0) | 7 (20.0) | |||

| Occupation | - | 0.079 b | |||

| Farmer | 43 (25.6) | 5 (14.3) | |||

| Worker | 41 (24.4) | 14 (40.0) | |||

| Technical staff | 22 (13.1) | 1 (2.9) | |||

| Merchant | 17 (10.1) | 2 (5.7) | |||

| others | 45 (26.8) | 13 (37.1) | |||

| Have a chronic disease | 1.692 | 0.267 a | |||

| Yes | 41 (24.4) | 5 (14.3) | |||

| No | 127 (75.6) | 30 (85.7) | |||

| Effect | β | SE | 95%CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The actor effect of survivors | ||||

| Direct effect | −3.731 | 0.589 | −5.014, −2.669 | 0.001 |

| Total effect | −0.817 | 0.553 | −5.219, −3.052 | 0.001 |

| Partner effects of spouse caregivers | ||||

| Indirect effect | ||||

T0 Disability  T1 Spouse caregiver depression T1 Spouse caregiver depression  T3 Spouse caregiver PCS T3 Spouse caregiver PCS | −0.037 | 0.106 | −0.468, −0.038 | 0.011 |

| Total effect | −0.092 | 0.231 | −0.946, −0.057 | 0.030 |

| Effect | β | SE | 95%CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The actor effect of survivors | ||||

| Direct effect | −1.598 | 0.530 | −2.732, −0.641 | 0.001 |

| Indirect effect | ||||

T0 Disability  T1 Survivor depression T1 Survivor depression  T3 Survivor MCS T3 Survivor MCS | −0.104 | 0.287 | −1.279, −0.096 | 0.007 |

T0 Disability  T1 Survivor depression T1 Survivor depression  T2 Survivor social support T2 Survivor social support T3 Survivor MCS T3 Survivor MCS | −0.462 | 0.134 | −0.643, −0.062 | 0.003 |

T0 Disability  T1 Spouse caregiver depression T1 Spouse caregiver depression  T2 Survivor social support T2 Survivor social support  T3 Survivor MCS T3 Survivor MCS | −0.312 | 0.117 | −0.515, −0.023 | 0.012 |

| Total effect | −2.439 | 0.621 | −3.458, −1.007 | 0.001 |

| Partner effects of spouse caregivers | ||||

| Direct effect | −1.001 | 0.351 | −1.727, −0.325 | 0.003 |

| Indirect effect | ||||

T0 Disability  T1 Survivor depression T1 Survivor depression  T2 Survivor social support T2 Survivor social support  T3 Spouse caregiver MCS T3 Spouse caregiver MCS | −0.566 | 0.050 | −0.207, 0.000 | 0.049 |

T0 Disability  T1 Spouse caregiver depression T1 Spouse caregiver depression T2 Survivor social support T2 Survivor social support  T3 Spouse caregiver MCS T3 Spouse caregiver MCS | −0.306 | 0.036 | −0.163, −0.002 | 0.038 |

| Total effect | −1.896 | 0.412 | −2.261, −0.650 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.-T.; Xiang, D.-D.; Ge, S.; Wang, S.-S.; Xie, J.-F.; Liu, Z.-W.; Zhang, S.-X.; Zhang, Z.-X.; Chen, S.-Y.; Li, X.; et al. The Interplay of Disability, Depression, Social Support, and Quality of Life in Middle-Aged and Young Couples Affected by Stroke: A Dyadic Path Analysis Using the Actor–Partner Interdependence Mediation Model. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 372. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15100372

Liu Y-T, Xiang D-D, Ge S, Wang S-S, Xie J-F, Liu Z-W, Zhang S-X, Zhang Z-X, Chen S-Y, Li X, et al. The Interplay of Disability, Depression, Social Support, and Quality of Life in Middle-Aged and Young Couples Affected by Stroke: A Dyadic Path Analysis Using the Actor–Partner Interdependence Mediation Model. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(10):372. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15100372

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Ya-Ting, Dan-Dan Xiang, Song Ge, Shan-Shan Wang, Jun-Fang Xie, Zhi-Wei Liu, Si-Xun Zhang, Zhen-Xiang Zhang, Su-Yan Chen, Xin Li, and et al. 2025. "The Interplay of Disability, Depression, Social Support, and Quality of Life in Middle-Aged and Young Couples Affected by Stroke: A Dyadic Path Analysis Using the Actor–Partner Interdependence Mediation Model" Nursing Reports 15, no. 10: 372. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15100372

APA StyleLiu, Y.-T., Xiang, D.-D., Ge, S., Wang, S.-S., Xie, J.-F., Liu, Z.-W., Zhang, S.-X., Zhang, Z.-X., Chen, S.-Y., Li, X., & Mei, Y.-X. (2025). The Interplay of Disability, Depression, Social Support, and Quality of Life in Middle-Aged and Young Couples Affected by Stroke: A Dyadic Path Analysis Using the Actor–Partner Interdependence Mediation Model. Nursing Reports, 15(10), 372. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15100372