Telehealth Family Psychoeducation for Major Depressive Disorder: A Protocol for Intervention Co-Design and Feasibility Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To develop SPARKED through the involvement of patients, patients’ families, and mental health professionals.

- To determine the feasibility of SPARKED through assessing recruitment and retention rates.

- To determine the feasibility of outcome measure completion and return rates.

- To determine the acceptability of SPARKED at pre-intervention, during intervention delivery, and post-intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

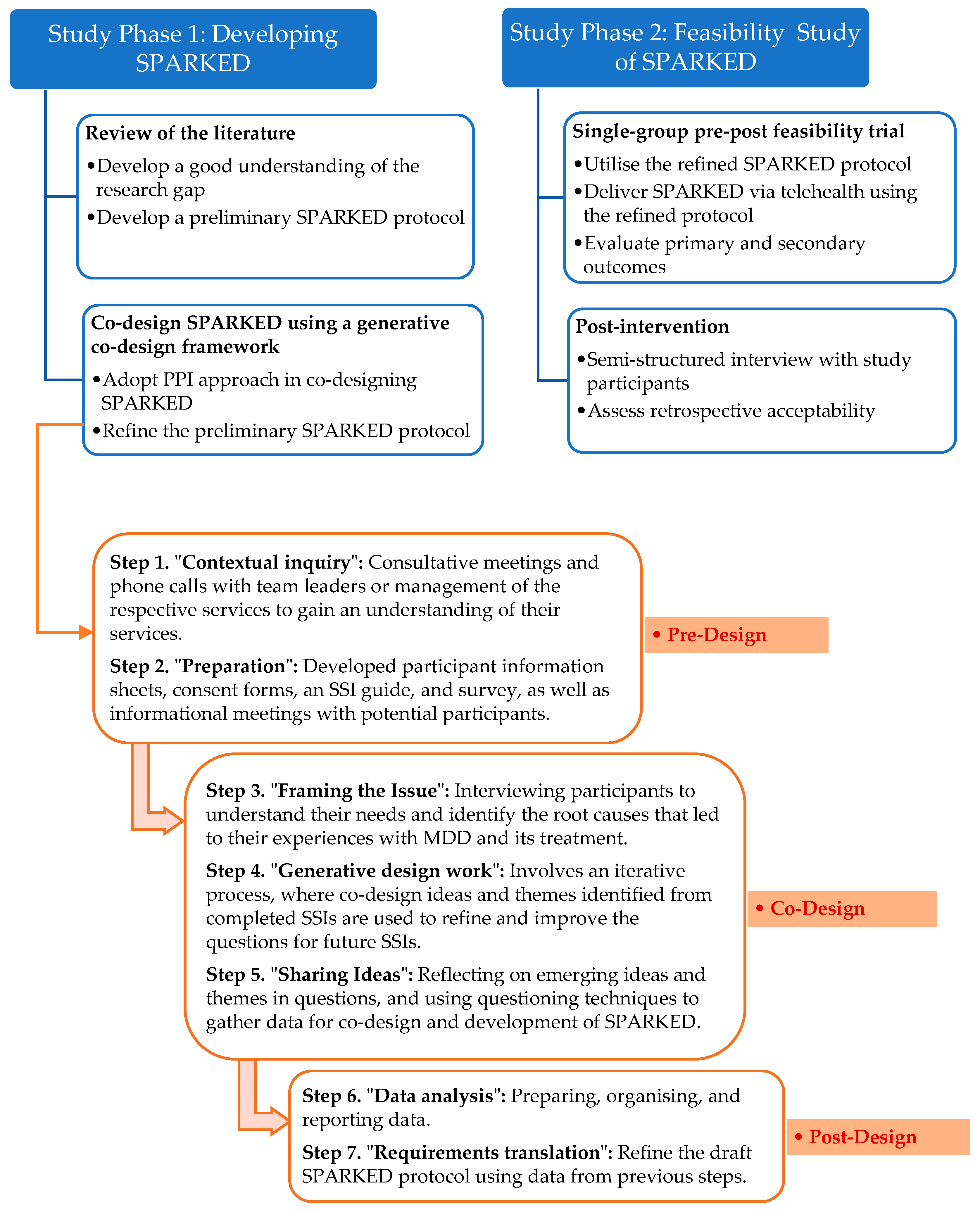

2.1. Overall Study Design

2.2. Study Phase 1: Developing SPARKED

2.2.1. Study Design

- Semi-structured interviews (SSIs) with patients diagnosed with MDD and their families;

- Surveys of mental health professionals;

- Focus group of mental health professionals.

2.2.2. Study Setting

2.2.3. Semi-Structured Interviews with Patients and Their Family Members

Sample and Sampling

Study Procedure

Data Analysis

2.2.4. Surveys of Mental Health Professionals

Sample and Sampling

Study Procedure

Data Analysis

2.2.5. Focus Group of Mental Health Professionals

Sample and Sampling

Study Procedure

Data Analysis

2.3. Study Phase 2: Feasibility Study of SPARKED

2.3.1. Study Design

2.3.2. Study Setting

2.3.3. Participants and Sample Size

2.3.4. Study Intervention

2.3.5. Study Procedure

2.3.6. Treatment Integrity

2.3.7. Outcome Measures

Primary Outcomes

- Recruitment rate: The main feasibility outcome of this study is the recruitment rate, which was referred to in the sample size calculation. The recruitment rate is defined as the percentage of eligible participant dyads who consented to participate in the study. The observed proportion (E) will be described based on the following pre-defined thresholds: the trial is feasible (if E ≥ 70%); the trial may be feasible, so proceed with caution (if E falls between 33 and 70%); and the trial is unfeasible to proceed (E ≤ 33%).

- Retention rate: This is defined as the percentage of participants who remain in the study throughout the entire study period, from enrolment to follow-up (Week 12). The observed proportion (E) will be described in the same way as the recruitment rate.

- Outcome measure return rate: Defined as the percentage of participants who return filled-out self-report measures at enrolment, immediately post-intervention (Week 6), and at follow-up (Week 12).

- Outcome measure completion rate: Defined as the percentage of participants who successfully complete each secondary outcome measure at enrolment, immediately post-intervention (Week 6), and at follow-up (Week 12).

- Prospective acceptability-related outcome: The number of eligible participants who consented to study participation.

- Concurrent acceptability-related outcome: The number of SPARKED sessions attended and the reasons for dropout during the study period, from enrolment to the follow-up (Week 12).

- Retrospective acceptability-related outcome: Feedback on SPARKED delivered via telehealth will be assessed through SSIs using an SSI guide (Supplementary Material, Table S4) at follow-up (Week 12).

Secondary Outcomes

- Personal recovery among patients: This outcome refers to subjective recovery, which will be assessed using the Recovery Assessment Scale-Domains and Stages (RAS-DS), a 38-item self-rated measure of personal recovery [54]. Studies have shown that RAS-DS is relevant to recovery [55] and demonstrates good reliability and validity, reflecting mental health recovery [56].

- Adherence to antidepressant medication among patients: Antidepressant adherence will be assessed using the Medication Adherence Report Scale-5 (MARS-5, ©Professor Rob Horne), a five-item self-administered instrument that measures both intentional and unintentional nonadherence behaviours [59]. Studies show that MARS-5 is a reliable and valid adherence measure [59,60]. Besides, the wording in MARS-5 is non-judgmental, which may reduce the tendency to underreport medication nonadherence due to social desirability [59].

- Medication Necessity Beliefs and Concerns among patients: Patients’ necessity beliefs and concerns about antidepressants will be assessed using the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ)-Specific 11 (BMQ-Specific 11, © Professor Rob Horne) [61]. This instrument comprises two scales: Specific-Necessity and Specific-Concerns [61] and has been reported as an effective tool for identifying patients at risk of medication nonadherence [62], which may be useful in developing interventions to address nonadherence.

2.3.8. Risk Mitigation Plan and Data Management

2.3.9. Quality Assurance and Data Analysis

3. Planned Reporting of Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FPE | Family psychoeducation |

| MDD | Major depressive disorder |

| MRC | Medical Research Council |

| SPARKED | Supportive Program for Advancing Recovery, Knowledge, and Empowerment in Depression |

| SSI | Semi-structured interview |

References

- World Health Organisation. Depressive Disorder (Depression). 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013; p. 161. Available online: https://archive.org/details/APA-DSM-5/mode/2up (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Greenberg, P.; O’Callaghan, L.; Fournier, A.-A.; Gagnon-Sanschagrin, P.; Maitland, J.; Chitnis, A. Impact of living with an adult with depressive symptoms among households in the United States. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 349, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, M.; Severus, E.; Möller, H.J.; Young, A.H. Pharmacological treatment of unipolar depressive disorders: Summary of WFSBP guidelines. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2017, 21, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhi, G.S.; Bell, E.; Singh, A.B.; Bassett, D.; Berk, M.; Boyce, P.; Bryant, R.; Gitlin, M.; Hamilton, A.; Hazell, P.; et al. The 2020 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders: Major depression summary. Bipolar Disord. 2020, 22, 788–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breznoscakova, D.; Pallayova, M.; Izakova, L.; Kralova, M. In-person psychoeducational intervention to reduce rehospitalizations and improve the clinical course of major depressive disorder: A non-randomized pilot study. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1429913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäuml, J.; Froböse, T.; Kraemer, S.; Rentrop, M.; Pitschel-Walz, G. Psychoeducation: A basic psychotherapeutic intervention for patients with schizophrenia and their families. Schizophr. Bull. 2006, 32, S1–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkhel, S.; Singh, O.P.; Arora, M. Clinical practice guidelines for psychoeducation in psychiatric disorders general principles of psychoeducation. Indian J. Psychiatry 2020, 62, S319–S323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saroca, K.; Sargent, J. Understanding families as essential in psychiatric practice. Focus 2022, 20, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, H.S.; Fernandez, P.A.; Lim, H.K. Family engagement as part of managing patients with mental illness in primary care. Singapore Med. J. 2021, 62, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsuki, F.; Watanabe, N.; Yamada, A.; Hasegawa, T. Effectiveness of family psychoeducation for major depressive disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BJPsych Open 2022, 8, e148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuki, F.; Takeuchi, H.; Inagaki, T.; Maeda, T.; Kubota, Y.; Shiraishi, N.; Tabuse, H.; Kato, T.; Yamada, A.; Watanabe, N.; et al. Brief multifamily psychoeducation for family members of patients with chronic major depression: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, P.; Kangas, M.; McGill, K. “Family Matters”: A systematic review of the evidence for family psychoeducation for major depressive disorder. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2017, 43, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalgard, O.S. A randomized controlled trial of a psychoeducational group program for unipolar depression in adults in Norway (NCT00319540). Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2006, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirey, J.A.; Banerjee, S.; Marino, P.; Bruce, M.L.; Halkett, A.; Turnwald, M.; Chiang, C.; Liles, B.; Artis, A.; Blow, F.; et al. Adherence to depression treatment in primary care: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 1129–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazu, K.; Shimodera, S.; Mino, Y.; Nishida, A.; Kamimura, N.; Sawada, K.; Fujita, H.; Furukawa, T.A.; Inoue, S. Family psychoeducation for major depression: Randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 198, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oneib, B.; Mansour, A.; Bouazzaoui, M.A. The effect of psychoeducation on clinical symptoms, adherence, insight and autonomy in patients with schizophrenia. Discov. Ment. Health 2025, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; O’Leary, K.D.; Foran, H. A randomized clinical trial of a brief, problem-focused couple therapy for depression. Behav. Ther. 2010, 41, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinton, L.; La Frano, E.; Harvey, D.; Alfaro, E.D.; Kravitz, R.; Smith, A.; Apesoa-Varano, E.C.; Jafri, A.; Unutzer, J. Feasibility of a family-centered intervention for depressed older men in primary care. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 34, 1808–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Gupta, M. Effectiveness of psycho-educational intervention in improving outcome of unipolar depression: Results from a randomised clinical trial. East Asian Arch. Psychiatry 2015, 25, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Thorburn, K.; Aadam, B.; Waks, S.; Bellingham, B.; Harris, M.F.; Fisher, K.R.; Spooner, C. Mental health consumers and primary care providers co-designing improvements and innovations: A scoping review. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2025, 31, PY24104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawke, L.D.; Sheikhan, N.Y.; Bastidas-Bilbao, H.; Rodak, T. Experience-based co-design of mental health services and interventions: A scoping review. SSM-Ment. Health 2024, 5, 100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergholtz, J.; Wolf, A.; Crine, V.; Cleeve, H.; Santana, M.-J.; Björkman, I. Patient and public involvement in healthcare: A systematic mapping review of systematic reviews—Identification of current research and possible directions for future research. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e083215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, A.; Schroter, S.; Snow, R.; Hicks, M.; Harmston, R.; Staniszewska, S.; Parker, S.; Richards, T. Frequency of reporting on patient and public involvement (PPI) in research studies published in a general medical journal: A descriptive study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Pipatpiboon, N.; Bressington, D. How can we enhance patient and public involvement and engagement in nursing science? Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmsen, S.; Pittens, C.A.C.M.; Vroonland, E.; Van Rensen, A.J.M.L.; Broerse, J.E.W. Supporting health researchers to realize meaningful patient involvement in research: Exploring researchers’ experiences and needs. Sci. Public Policy 2022, 49, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.D.; Li, D.H.; Merle, J.L.; Keiser, B.; Mustanski, B.; Benbow, N.D. Adjunctive interventions: Change methods directed at recipients that support uptake and use of health innovations. Implement. Sci. 2024, 19, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobeissi, M.M.; Manning, C.A. ACCESS Enabled: More equitable telehealth for people with disabilities. J. Nurse Pract. 2025, 21, 105451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, S.S.; Kalra, S.; Mahmood, A.; Rai, A.; Bordoloi, K.; Basu, U.; O’Callaghan, E.; Gardner, M. Motivation and use of telehealth among people with depression in the United States. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2024, 15, 21501319241266515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton, M.; Sullivan, E.E.; Deville-Stoetzel, N.; McKinstry, D.; Depuccio, M.; Sriharan, A.; Deslauriers, V.; Dong, A.; McAlearney, A.S. Telehealth challenges during COVID-19 as reported by primary healthcare physicians in Quebec and Massachusetts. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajarawala, S.N.; Pelkowski, J.N. Telehealth benefits and barriers. J. Nurse Pract. 2021, 17, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykgraaf, S.H.; Desborough, J.; Sturgiss, E.; Parkinson, A.; Dut, G.M.; Kidd, M. Older people, the digital divide and use of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2022, 51, 721–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handrup, C. Statement of the International Society for Psychiatric Mental Health Nurses. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2022, 38, A1–A2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, C.S.; Krowski, N.; Rodriguez, B.; Tran, L.; Vela, J.; Brooks, M. Telehealth and patient satisfaction: A systematic review and narrative analysis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterton, M.L.; Marangu, E.; Clancy, E.M.; Mackay, M.; Gu, E.; Moylan, S.; Langbein, A.; O’Shea, M. Telehealth service delivery in an Australian regional mental health service during COVID-19: A mixed methods analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2022, 16, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molfenter, T.; Heitkamp, T.; Murphy, A.A.; Tapscott, S.; Behlman, S.; Cody, O.J. Use of telehealth in mental health (MH) services during and after COVID-19. Community Ment. Health J. 2021, 57, 1244–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangani, C.; Ostinelli, E.G.; Smith, K.A.; Hong, J.S.W.; Macdonald, O.; Reen, G.; Reid, K.; Vincent, C.; Syed Sheriff, R.; Harrison, P.J.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the global delivery of mental health services and telemental health: Systematic review. JMIR Ment. Health 2022, 9, e38600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E.; et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, M.; McGillion, M.; Chambers, E.M.; Dix, J.; Fajardo, C.J.; Gilmour, M.; Levesque, K.; Lim, A.; Mierdel, S.; Ouellette, C.; et al. A generative co-design framework for healthcare innovation: Development and application of an end-user engagement framework. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2021, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Grieken, R.A.; Beune, E.J.; Kirkenier, A.C.; Koeter, M.W.; van Zwieten, M.C.; Schene, A.H. Patients’ perspectives on how treatment can impede their recovery from depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 167, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, R.; Weinman, J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J. Psychosom. Res. 1999, 47, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Family Studies. Australian Legal Definitions: When Is a Child in Need of Protection? 2023. Available online: https://aifs.gov.au/resources/resource-sheets/australian-legal-definitions-when-child-need-protection (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.A.; Ting, H.; Cheah, J.-H.; Thurasamy, R.; Chuah, F.; Cham, T.H. Sample size for survey research: Review and recommendations. J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Model. 2020, 4, i–xx. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; McKenna, K. How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field Methods 2017, 29, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tausch, A.P.; Menold, N. Methodological aspects of focus groups in health research. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2016, 3, 2333393616630466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, I.C.D.S.; Theiss, L.M.; Johnson, C.Y.; McLin, E.; Ruf, B.A.; Vickers, S.M.; Fouad, M.N.; Scarinci, I.C.; Chu, D.I. Implementation of virtual focus groups for qualitative data collection in a global pandemic. Am. J. Surg. 2021, 221, 918–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South Western Sydney PHN. Suicide Risk Screening Tool. Available online: https://swsphn.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/SWSPHN-Clinical-Suicide-Risk-Assessment-Word-pdf.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- SS-PROGRESS WebApp. Available online: https://ss-progress.shinyapps.io/ss_progress_app/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Lewis, M.; Bromley, K.; Sutton, C.J.; McCray, G.; Myers, H.L.; Lancaster, G.A. Determining sample size for progression criteria for pragmatic pilot RCTs: The hypothesis test strikes back! Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2021, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhon, M.; Cartwright, M.; Francis, J.J. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: An overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancock, N.; Scanlan, J.N.; Bundy, A.C.; Honey, A. Recovery Assessment Scale—Domains and Stages (RAS-DS); University of Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 2019; Version 3; Available online: https://ras-ds.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/RASDS-Manual-Version-3-2019-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Ramesh, S.; Scanlan, J.N.; Honey, A.; Hancock, N. Feasibility of Recovery Assessment Scale—Domains and Stages (RAS-DS) for everyday mental health practice. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1256092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, N.; Scanlan, J.N.; Honey, A.; Bundy, A.C.; O’Shea, K. Recovery assessment scale–domains and stages (RAS-DS): Its feasibility and outcome measurement capacity. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2015, 49, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: A systematic review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2010, 32, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Fu, Z.; Bo, Q.; Mao, Z.; Ma, X.; Wang, C. The reliability and validity of PHQ-9 in patients with major depressive disorder in psychiatric hospital. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.H.Y.; Horne, R.; Hankins, M.; Chisari, C. The Medication Adherence Report Scale: A measurement tool for eliciting patients’ reports of nonadherence. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 86, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Ou, H.-t.; Nikoobakht, M.; Broström, A.; Årestedt, K.; Pakpour, A.H. Validation of the 5-item medication adherence report scale in older stroke patients in Iran. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2018, 33, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, R.; Weinman, J.; Hankins, M. The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: The development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol. Health 1999, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrijević, I. Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ) in patients with chronic pain. Acta Clin. Croat. 2023, 62, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, B.; Brown, G.K. Safety planning intervention: A brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2012, 19, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. The ICH Harmonised Guideline, Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R3). 2025, pp. 1–86. Available online: https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/ICH_E6%28R3%29_Step4_FinalGuideline_2025_0106.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Fekadu, W.; Mihiretu, A.; Craig, T.K.J.; Fekadu, A. Multidimensional impact of severe mental illness on family members: Systematic review. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e032391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastuszak, M.; Cubała, W.J.; Kwaśny, A.; Mechlińska, A. The search for consistency in residual symptoms in major depressive disorder: A narrative review. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, R.; Munkholm, K.; Christensen, M.S.; Kessing, L.V.; Vinberg, M. Functioning in patients with major depressive disorder in remission: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 363, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Infante-Ventura, D.; Rodríguez-Díaz, B.; Bello, M.Á.G.; Valcárcel-Nazco, C.; Estupiñán-Romero, F.; Artiles, F.J.A.; de León, B.G.; Hurtado-Navarro, I.; del Pino-Sedeño, T. Analysis of therapeutic adherence to antidepressants and associated factors in patients with depressive disorder: A population-based cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 385, 119443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semahegn, A.; Torpey, K.; Manu, A.; Assefa, N.; Tesfaye, G.; Ankomah, A. Psychotropic medication non-adherence and its associated factors among patients with major psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, A.; Furukawa, T.A.; Salanti, G.; Chaimani, A.; Atkinson, L.Z.; Ogawa, Y.; Leucht, S.; Ruhe, H.G.; Turner, E.H.; Higgins, J.P.T.; et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2018, 391, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, K.; Lau, W.K.; Sim, J.; Sum, M.Y.; Baldessarini, R.J. Prevention of relapse and recurrence in adults with major depressive disorder: Systematic review and meta-analyses of controlled trials. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016, 19, pyv076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unni, E.J.; Gupta, S.; Sternbach, N. Reasons for non-adherence with antidepressants using the Medication Adherence Reasons Scale in five European countries and United States. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 344, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges Do Nascimento, I.J.; Abdulazeem, H.; Vasanthan, L.T.; Martinez, E.Z.; Zucoloto, M.L.; Østengaard, L.; Azzopardi-Muscat, N.; Zapata, T.; Novillo-Ortiz, D. Barriers and facilitators to utilizing digital health technologies by healthcare professionals. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrow, K.; Farmer, A.; Cishe, N.; Nwagi, N.; Namane, M.; Brennan, T.P.; Springer, D.; Tarassenko, L.; Levitt, N. Using the Medical Research Council framework for development and evaluation of complex interventions in a low resource setting to develop a theory-based treatment support intervention delivered via SMS text message to improve blood pressure control. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kan, K.; Jörg, F.; Buskens, E.; Schoevers, R.A.; Alma, M.A. Patients’ and clinicians’ perspectives on relevant treatment outcomes in depression: Qualitative study. BJPsych Open 2020, 6, e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotterill, S.; Knowles, S.; Martindale, A.-M.; Elvey, R.; Howard, S.; Coupe, N.; Wilson, P.; Spence, M. Getting messier with TIDieR: Embracing context and complexity in intervention reporting. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Element | SPARKED Protocol |

|---|---|

| Type of intervention | Family psychoeducation |

| Study participants | Patients with MDD and family members, carers or significant others |

| Mode of delivery | Telephone or videoconferencing |

| Format | Single-family |

| Number of SPARKED sessions | Three |

| Frequency of sessions | Bi-weekly |

| Session duration | 45–60 min |

| Intervention duration | Six weeks |

| Follow-up | At Week 12 (six-week post-intervention) |

| Outcome measurement timepoints | At baseline, immediately after intervention, and at follow-up |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Obieche, O.; Tan, J.-Y.; Sharma, S.; Bressington, D.; Wang, T. Telehealth Family Psychoeducation for Major Depressive Disorder: A Protocol for Intervention Co-Design and Feasibility Study. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15100364

Obieche O, Tan J-Y, Sharma S, Bressington D, Wang T. Telehealth Family Psychoeducation for Major Depressive Disorder: A Protocol for Intervention Co-Design and Feasibility Study. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(10):364. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15100364

Chicago/Turabian StyleObieche, Obumneke, Jing-Yu (Benjamin) Tan, Sita Sharma, Daniel Bressington, and Tao Wang. 2025. "Telehealth Family Psychoeducation for Major Depressive Disorder: A Protocol for Intervention Co-Design and Feasibility Study" Nursing Reports 15, no. 10: 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15100364

APA StyleObieche, O., Tan, J.-Y., Sharma, S., Bressington, D., & Wang, T. (2025). Telehealth Family Psychoeducation for Major Depressive Disorder: A Protocol for Intervention Co-Design and Feasibility Study. Nursing Reports, 15(10), 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15100364