Breast Ironing from the Perspective of Transcultural Nursing by Madeleine Leininger: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

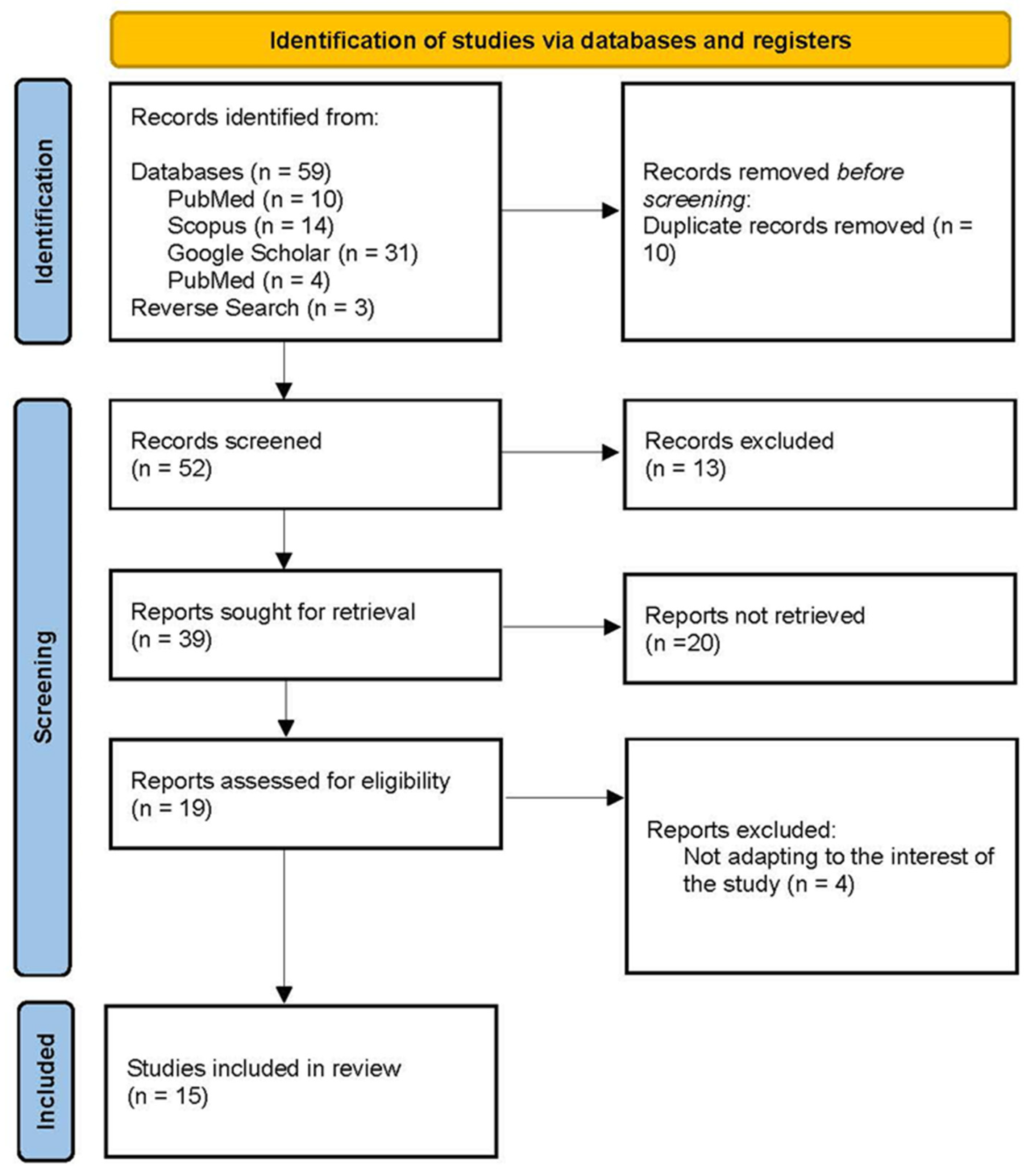

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results/Discussion

3.1. Breast Ironing: A Cultural Practice and Its Impact on Women’s Health and Rights

3.2. Transcultural Nursing Theory: Promoting Integrated Care in a Diverse World

3.3. Factors Perpetuating the Practice of Breast Ironing

3.4. A Grave Violation of Women’s Human Rights and Physical Integrity

3.5. Challenges of Transcultural Nursing in Addressing Breast Ironing

3.6. The Application of Transcultural Theory in the Nursing Care of Women Affected by Breast Ironing

3.7. Community Nursing Intervention Proposal to Eradicate Breast Ironing

- Raising community awareness about the risks of breast ironing.

- Empowering girls, adolescents, and women with knowledge about their rights and health.

- Engaging men, community leaders, and religious figures to transform cultural norms.

- Promoting cultural and social alternatives to protect girls from gender-based violence.

- Community Sensitization and Education: Organize community talks in local centers to explain what breast ironing is, its harmful effects, and human and children’s rights. Include testimonies from survivors to share personal experiences. As concluding actions, use videos or social theater dramatizations to showcase alternatives to the practice and address its challenges.

- Educational Programs in Schools: Integrate lessons on sexual and reproductive health, puberty, body acceptance, and the consequences of breast ironing into school curriculums. Conduct self-esteem and empowerment workshops, and provide teacher training on gender and health issues.

- Empowerment of Mothers: Establish women’s support groups as safe spaces to discuss the motivations behind breast ironing and explore alternative protective measures for daughters. Offer training in income-generating skills to provide mothers with economic independence and reduce reliance on patriarchal norms.

- Engaging Men and Community Leaders: Implement male leadership training programs to raise awareness among men. Facilitate intergenerational debates to encourage respectful discussions about traditions and their impact on girls’ health.

- Creation of Support and Prevention Networks: Form community child protection committees to collaborate with health services and local authorities, creating a robust network for prevention and support.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amahazion, F. Breast ironing: A brief overview of an underreported harmful practice. J. Glob. Health 2021, 11, 03055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Harmful Practices. Datos de UNICEF: Seguimiento de la Situación de los Niños y las Mujeres. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- United Nations. Peace, Dignity and Equality on a Healthy Planet. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/es/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Temmerman, M.; Khosla, R.; Say, L. Sexual and reproductive health and rights: A global development, health, and human rights priority. Lancet 2024, 384, e30–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, P.; Merry, S.E. Vernacularization on the ground: Local uses of global women’s rights in Peru, China, India and the United States. Glob. Netw. 2009, 9, 441–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibanyoni, E.K. Perspectives on Cultural Practices that Victimize Female Children in Africa. In Peace, Safety and Security: African Perspectives; Peter Lang: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2022; pp. 177–200. ISBN 9783631892770. [Google Scholar]

- Cislaghi, B.; Heise, L. Theory and practice of social norms interventions: Eight common pitfalls. Glob. Health 2018, 14, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olusola Ajibade, B.; Ubah, P.; Kainesie, J.; Suleiman, U.; Omoruyi, M.; Tolulope Olubunmi, A.I. Mapping the Shadows: A Comprehensive Exploration of Breast Ironing’s Effects on Women and Girls through a Systematic and Scoping Review. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, I.G.; Medrano, E.M.; Burró, A.M.A.; Reviriego, A.M.; Valdés, E.A.; Camino, F.V. Breast ironing: Una realidad no justificable en el siglo XXI. Prog. Obstet. Ginecol. Rev. Of. Soc. Esp. Ginecol. Obstet. 2015, 58, 202–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemunta, N.V. The Social Context of Breast Ironing in Cameroon. Athens J. Health 2016, 3, 335–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz González, M.C. Enfermería transcultural: Reflexiones sobre la construcción del género. Garnata 2023, 91, 26. Available online: https://ciberindex.com/c/g91/e2621gt (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Alvear Arias, J.A.; Cachago González, J.M.; Peraza de Aparicio, C.X. Transculturalidad y rol de enfermería en atención primaria de salud. RECIMUNDO Rev. Cient. Investig. Conoc. 2021, 5, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leininger, M.; McFarland, M. Transcultural Nursing: Concepts, Theories, Research and Practice, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1995; ISBN 0071353976. [Google Scholar]

- Lasmaida, S.A.; Dedi, B. Literature Review Teori Transcultural Nursing Madeleine Leininger. J. Soc. Res. 2024, 3, 668–681. Available online: https://ijsr.internationaljournallabs.com/index.php/ijsr/article/view/2028/1185 (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- McFarland, M.R.; Wehbe-Alamah, H.B. Leininger’s Theory of Culture Care Diversity and Universality: An Overview with a Historical Retrospective and a View Toward the Future. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2019, 30, 540–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hankivsky, O.; Cormier, R. Intersectionality and Public Policy: Some Lessons from Existing Models. Political Res. Q. 2010, 64, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraway, D. Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Fem. Stud. 1988, 14, 575–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.M.; Boyle, J.S. Transcultural Concepts in Nursing Care, 7th ed.; Wolters Kluwer Health: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015; ISBN 1451193971. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, F. Breast ironing. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2019, 365, l1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, H. Global midwifery series: Raising awareness of breast ironing practices and prevention. Pract. Midwife 2018, 21, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyangweso, M. Contending with Health Outcomes of Sanctioned Rituals: The Case of Puberty Rites. Religions 2022, 13, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover Williams, A.; Finlay, F. Breast ironing: An under-recognised form of gender-based violence. Arch. Dis. Child. 2020, 105, 90–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorar, M. Breast Ironing in the UK and Domestic Law. J. Int. Women’s Stud. 2022, 24, 34. Available online: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol24/iss1/34 (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Falana, T.C. Breast ironing: A rape of the girl -child’s personality integrity and sexual autonomy. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Educ. J. 2022, 1, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkwelle, N.N.N. The Long-Term Health-Related Outcomes of Breast Ironing in Cameroon. Ph.D. Thesis, Walden University, Walden, MN, USA, 2019. Available online: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/7049 (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Chishugi, J.; Franke, T. Sexual Abuse in Cameroon: A Four-Year-Old Girl Victim of Rape in Buea Case Study. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2016, 25, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djiemo, C. The Practice of Breast Ironing in Cameroon: A Qualitative Interview Study with Women, Healthcare Professionals and Community Stakeholders. Ph.D. Thesis, Dalarna University, Falun, Sweden, 2023. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?dswid=8782&pid=diva2%3A1783287 (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Fotabong, M.; Obajimi, G.; Lawal, T.; Morhason-Bello, I. Prevalence, Awareness and Adverse Outcomes of Breast Ironing Among Cameroonian Women in Buea Health District. Med. J. Zamb. 2023, 49, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi Olofinbiyi, B.; Oluwole Enoch, O.; Oluwafunke Olofinbiyi, R.; Olumuyiwa Awoleke, J. Breast ironing: A Clandestine Variant of Gender-based Violence in Africa. Sierra Leone J. Med. 2024, 1, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, C. Niñas sin Pecho en Camerún. El País. 2011. Available online: https://elpais.com/diario/2011/09/12/sociedad/1315778405_850215.html (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Tapscott, R. Understanding Breast “Ironing”: A Study of the Methods, Motivations and Outcomes of Breast Flattening Practices in Cameroon. Feinstein International Center. 2012. Available online: https://fic.tufts.edu/wp-content/uploads/Understanding-breast-flattening.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Mujeres Para la Salud. Breast Ironing. 2021. Available online: https://www.mujeresparalasalud.org/planchado-de-senos/ (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Pearsell, R. The Harmful Traditional Practice of Breast Ironing in Cameroon, Africa. Bridges Undergrad. J. Contemp. Connect. 2017, 2, 3. Available online: https://scholars.wlu.ca/bridges_contemporary_connections/vol2/iss1/3 (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Busher Betancourt, D.A. Madeleine Leininger and the Transcultural Theory of Nursing. Downt. Rev. 2015, 2, 1. Available online: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/tdr/vol2/iss1/1 (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Correa Júnior, A.J.S.; Santana, M.E. Corporeidade, transpessoalidade e transculturalidade: Reflexões dentro do processo saúde-doença-cuidado. Cult. Cuid. 2020, 24, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemany-Arrebola, I.; Plaza del Pino, F.J.; Sánchez-Ojeda, M.A. Prejudiced Attitudes of Nursing Students in Southern Spain Toward Migrant Patients. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2021, 32, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, L.; Kinmond, K.; Humphreys, J.; Dioum, M. Safeguarding children who are exposed to abuse linked to faith or belief. Child Abus. Rev. 2019, 28, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, N. Avances, Retrocesos y Retos para las Niñas. Balance Retos Futuro 2015, 118, 56–63. Available online: https://revistatiempodepaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/TP-118-Beijing-20-Balance-y-Retos-de-Futuro.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- United Nations. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Concluding Observations of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women: Cameroon. 2009. Available online: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n09/226/16/pdf/n0922616.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Law No. 96/06 of January 18, 1996, Constitution in Cameroon. Available online: https://www.wipo.int/wipolex/es/legislation/details/7391 (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Law No. 2016/007 of July 12, 2016, Relating to the Penal Code. Available online: https://www.wipo.int/wipolex/es/legislation/details/16366 (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Fornons Fontdevila, D. Madeleine Leininger: Claroscuro trascultural. Index Enferm. 2010, 19, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peraza de Aparicio, C.X.; Nicolalde Vásquez, M.I. El pensamiento de Leininger y la vinculación con la sociedad. Recimundo 2023, 7, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guber, R. La Etnografía: Método, Campo y Reflexividad, 1st ed.; Siglo Veintiuno: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2011; ISBN 9789876291576. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos Melguizo, R.; Cabeza Herrera, O. El principio del determinismo en el materialismo cultural. Rev. Temas 2013, 7, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchoukou, J.A. Introducing the Practice of Breast Ironing as a Human Rights Issue in Cameroon. J. Civivil Leg. Sci. 2014, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Study Aim | Study Design and Methods | Main Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| [1] Amahazion F. (2021) | Provide a brief overview of the practice, discuss its underlying causes, analyze its health implications, and present recommendations | Narrative review | It requires legislative frameworks prohibiting the practice, comprehensive sexuality education that addresses gender-based violence, and social and cultural paradigm shifts in communities where it occurs. |

| [2] Sibanyoni E.K. (2022) | Book chapter | Narrative review | Education and awareness campaigns are recommended to inform and highlight the dangers of cultural practices that threaten the well-being of girls. |

| [8] Olusola Ajibade, B., et al. (2024) | Examine the cultural practice of breast ironing and its significant impact on the physical, psychological, and social well-being of women and girls | Systematic scoping review following PRISMA guidelines | Breast ironing is a harmful cultural practice with significant negative impacts on the health and well-being of women and girls. Comprehensive interventions, including legal measures, community education, and support services, are crucial to eliminating this practice and protecting the rights and health of those affected. |

| [9] Blanco, I.G., et al. (2015) | Not applicable | Letter to the editor | Perhaps progress is not being made in an organized manner from an educational and cultural standpoint regarding the erotic symbolism of a woman’s breasts. This may demonstrate men’s tight and abusive control over the female population, rooted in fear and insecurity when women are treated as equals in rights and responsibilities. |

| [19] Robinson F. (2019) | Determine the actions physicians should take if they suspect a case of breast ironing | Narrative review | The most effective approaches include community education and programs for young women, alongside health initiatives like those created by the Came Women and Girls Development Organisation. |

| [20] Simpson, H. (2018) | Investigate the practice of breast ironing in Africa and the UK | Narrative review | This public health issue has both physical and emotional implications, and the practice has spread to the UK. Raising awareness of breast ironing among health professionals is essential to support those affected and protect those at risk. |

| [21] Nyangweso M. (2022) | Explore rites of passage as they relate to health outcomes, such as breast ironing | Qualitative through interviews | These practices exemplify how rituals evoke health concerns in Africa. The rise of scientific knowledge and the classification of religious knowledge as non-scientific in the mid-nineteenth century led to the separation of physical healing from spiritual factors. |

| [22] Glover Williams, A., and Finlay, F. (2020) | Describe the characteristics of breast ironing and raise awareness of this this issue within the scientific community | Narrative review | When caring for girls from West Africa, health workers must be alert to the possibility that they may have been subjected to this practice. |

| [23] Gorar, M. (2022) | Analyze the practice of breast ironing | Narrative review | The purpose of breast ironing is, ultimately, to control both a girl’s body and sexuality. Since female sexual activities outside of marriage are perceived as a stain on a family’s name, this practice is rooted in patriarchal, honor-based values. |

| [24] Falana, T.C. (2022) | Analyze the practice of breast ironing from the perspective of universal human rights, particularly the right to personal integrity and sexual autonomy | Qualitative research, analytical expository method | This harmful practice is an abuse because it violates a girl’s right to full sexual autonomy and to possess the natural physiological attributes that adorn women. Strict laws and sanctions should be enacted to abolish and completely eradicate this barbaric and horrific mutilation. |

| [25] Nkwelle, N.N.N. (2019) | Examine the perceived long-term health outcomes of breast ironing and its effects on the quality of life for affected women | Quasi-experimental | Research revealed a strong link between women who experienced breast ironing and negative outcomes related to long-term physical, psychosocial, and emotional health, as well as a decline in quality of life during and after the practice. |

| [26] Chishugi, J., and Franke, T. (2016) | Determine the situation regarding sexual abuse of women in Cameroon | Qualitative: case study | Cameroon has adopted strategies aimed at eliminating violence against women, including ratifying international policies, revising penal codes, and supporting local and international initiatives that promote women’s rights. However, many of these laws remain largely symbolic. |

| [27] Djiemo, C. (2023) | Explore the experiences and perceptions of breast ironing in Cameroon from the perspectives of women, healthcare professionals, and community actors | Qualitative descriptive design | The practice of breast ironing is complex and contributes to both individual suffering and the deterioration of family relationships. Legislation is needed to ensure access to sex education for girls and boys, as well as for mothers and fathers. |

| [28] Fotabong, M., et al. (2023) | Investigate the prevalence, awareness, and adverse outcomes of breast ironing among Cameroonian women | Mixed method design involving a qualitative and cross-sectional study | Health education and the introduction of laws against breast ironing will go a long way in eliminating this harmful traditional practice. |

| [29] Ajayi Olofinbiyi, B., et al. (2024) | Examine the phenomenon of breast ironing within the broader context of gender-based violence in Africa, including its prevalence, socio-cultural roots, health consequences, social implications, prevention challenges, and intervention strategies | Narrative review | Political will and action are essential to preventing breast ironing in Africa. Leaders must prioritize legislation, allocate resources, and collaborate with stakeholders to eradicate this harmful practice and protect vulnerable individuals. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cárdaba-García, R.M.; Velasco-Gonzalez, V.; Cárdaba-García, I.; Pérez-Pérez, L.; Durantez-Fernández, C.; Muñoz-del Caz, A.; Soto-Cámara, R.; Aparicio-García, M.E.; Madrigal, M.; Pérez, I. Breast Ironing from the Perspective of Transcultural Nursing by Madeleine Leininger: A Narrative Review. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 3677-3688. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040269

Cárdaba-García RM, Velasco-Gonzalez V, Cárdaba-García I, Pérez-Pérez L, Durantez-Fernández C, Muñoz-del Caz A, Soto-Cámara R, Aparicio-García ME, Madrigal M, Pérez I. Breast Ironing from the Perspective of Transcultural Nursing by Madeleine Leininger: A Narrative Review. Nursing Reports. 2024; 14(4):3677-3688. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040269

Chicago/Turabian StyleCárdaba-García, Rosa M., Veronica Velasco-Gonzalez, Inés Cárdaba-García, Lucía Pérez-Pérez, Carlos Durantez-Fernández, Alba Muñoz-del Caz, Raúl Soto-Cámara, Marta Evelia Aparicio-García, Miguel Madrigal, and Inmaculada Pérez. 2024. "Breast Ironing from the Perspective of Transcultural Nursing by Madeleine Leininger: A Narrative Review" Nursing Reports 14, no. 4: 3677-3688. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040269

APA StyleCárdaba-García, R. M., Velasco-Gonzalez, V., Cárdaba-García, I., Pérez-Pérez, L., Durantez-Fernández, C., Muñoz-del Caz, A., Soto-Cámara, R., Aparicio-García, M. E., Madrigal, M., & Pérez, I. (2024). Breast Ironing from the Perspective of Transcultural Nursing by Madeleine Leininger: A Narrative Review. Nursing Reports, 14(4), 3677-3688. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040269