Positive Nursing Practice Environment: A Concept Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

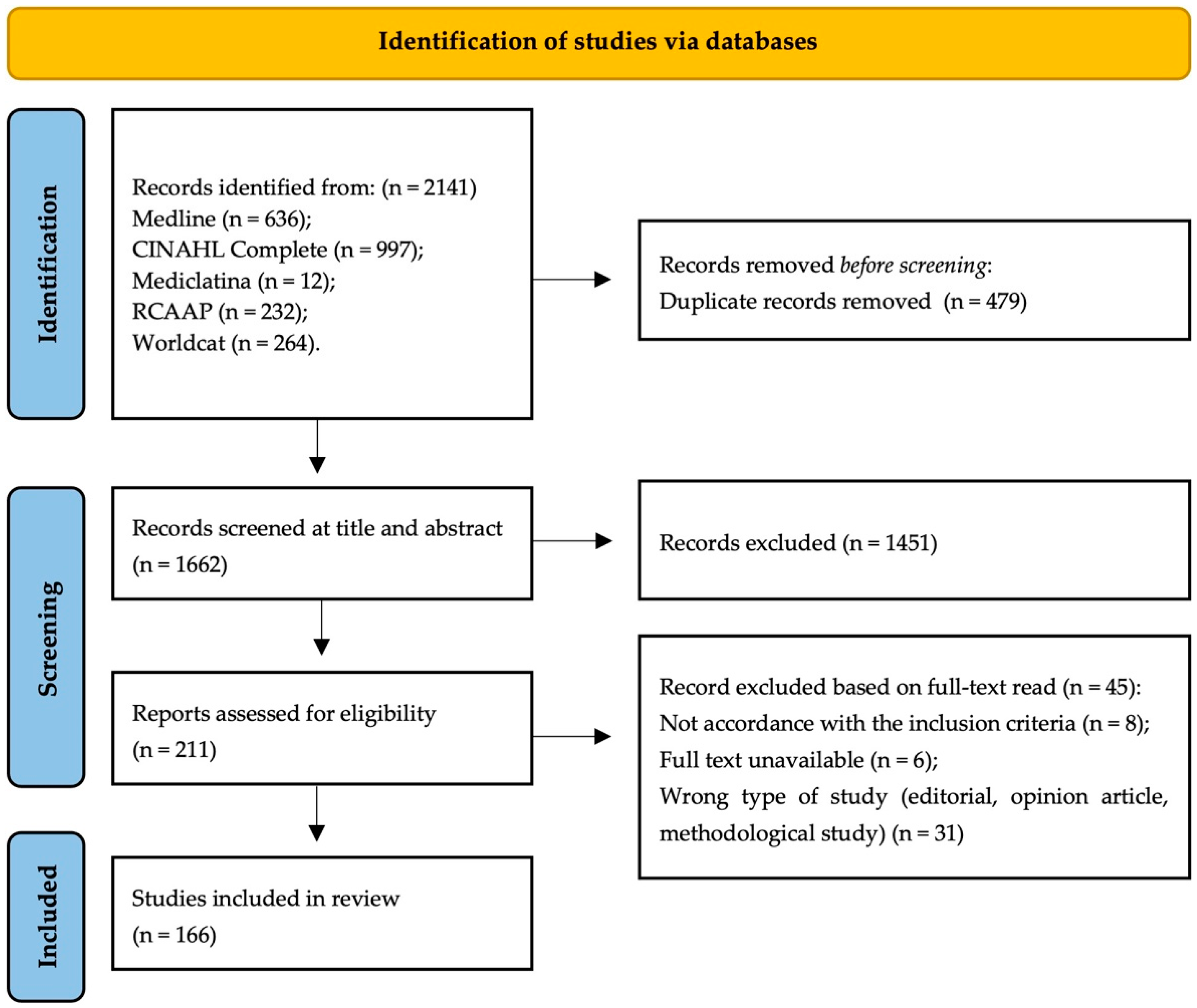

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Concept Analysis Method

2.2. Data Sources

3. Results

3.1. Uses of the Concept

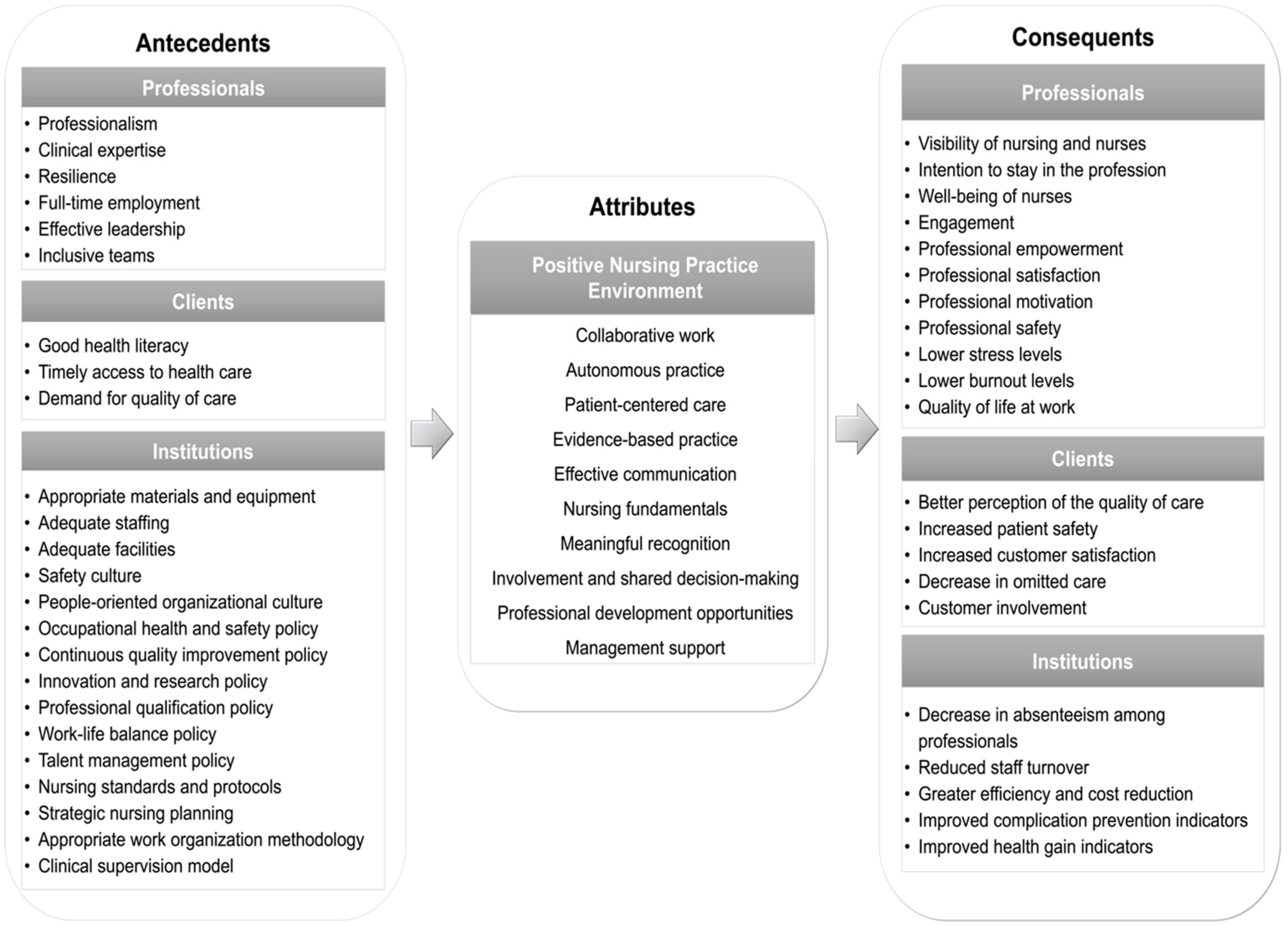

3.2. Defining Attributes

3.2.1. Collaborative Work

3.2.2. Autonomous Practice

3.2.3. Patient-Centered Care

3.2.4. Evidence-Based Practice

3.2.5. Effective Communication

3.2.6. Nursing Fundamentals

3.2.7. Meaningful Recognition

3.2.8. Involvement and Shared Decision-Making

3.2.9. Professional Development Opportunities

3.2.10. Management Support

3.3. Model Case

3.4. Additional Cases

3.4.1. Related Case

3.4.2. Contrary Case

3.5. Antecedents

3.5.1. Professionals

3.5.2. Clients

3.5.3. Institutions

3.6. Consequences

3.6.1. Professionals

3.6.2. Clients

3.6.3. Institutions

3.7. Empirical References

3.8. Definition of the Concept

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malinowska-Lipień, I.; Micek, A.; Gabryś, T.; Kózka, M.; Gajda, K.; Gniadek, A.; Brzostek, T.; Fletcher, J.; Squires, A. Impact of the Work Environment on Patients’ Safety as Perceived by Nurses in Poland-A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihdawi, M.; Al-Amer, R.; Darwish, R.; Randall, S.; Afaneh, T. The Influence of Nursing Work Environment on Patient Safety. Workplace Health Saf. 2020, 68, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarıköse, S.; Göktepe, N. Effects of Nurses’ Individual, Professional and Work Environment Characteristics on Job Performance. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, S.C.A.; Lopes Ribeiro, O.M.P.; Fassarella, C.S.; Santos, E.F. The Impact of Nursing Practice Environments on Patient Safety Culture in Primary Health Care: A Scoping Review. BJGP Open 2024, 4, BJGPO.2023.0062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Dossary, R.N. The Effects of Nursing Work Environment on Patient Safety in Saudi Arabian Hospitals. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 872091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paguio, J.T.; Yu, D.S.F. A Mixed Methods Study to Evaluate the Effects of a Teamwork Enhancement and Quality Improvement Initiative on Nurses’ Work Environment. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A. Keeping Patients Safe: Transforming the Work Environment of Nurses; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Patient Safety Action Plan 2021–2030: Towards Eliminating Avoidable Harm in Health Care; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lasater, K.B.; Richards, M.R.; Dandapani, N.B.; Burns, L.R.; McHugh, M.D. Magnet Hospital Recognition in Hospital Systems Over Time. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2019, 44, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graystone, R. The Value of Magnet® Recognition. J. Nurs. Adm. 2019, 49 (Suppl. S9), S1–S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordova, P.B.; Jones, T.; Riman, K.A.; Rogowski, J.; McHugh, M.D. Staffing Trends in Magnet and Non-Magnet Hospitals after State Legislation. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2020, 35, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrician, P.A.; Olds, D.M.; Breckenridge-Sproat, S.; Taylor-Clark, T.; Swiger, P.A.; Loan, L.A. Comparing the Nurse Work Environment, Job Satisfaction, and Intent to Leave Among Military, Magnet®, Magnet-Aspiring, and Non-Magnet Civilian Hospitals. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2022, 52, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, L.; Arneil, M.; Coventry, L.; Casey, V.; Moss, S.; Cavadino, A.; Laing, B.; McCarthy, A.L. Benchmarking Nurse Outcomes in Australian Magnet® Hospitals: Cross-Sectional Survey. BMC Nurs. 2019, 18, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, N. Creating Healthy Work Environments: Our Voice, Our Strength. AACN Adv. Crit. Care 2019, 30, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lake, E.T. Development of the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index. Res. Nurs. Health 2002, 25, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICN. Positive Practice Environments: Quality Workplaces, Quality Patient Care: Information and Action Tool Kit Developed by Andrea Baumann for ICN; ICN: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- RNAO. System and Healthy Work Environment Best Practice Guidelines Developing and Sustaining Safe, Effective Staffing and Workload Practices Second Edition; RNAO: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.; Sewell, K.A.; Woody, G.; Rose, M.A. The State of the Science of Nurse Work Environments in the United States: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2018, 5, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maassen, S.M.; Van Oostveen, C.; Vermeulen, H.; Weggelaar, A.M. Defining a Positive Work Environment for Hospital Healthcare Professionals: A Delphi Study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.O.; Avant, K.C. Concept Analysis. In Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing; Pearson Education, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 167–192. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 Version). In JBI Reviewer’s Manual; Joanna Briggs Institute: Synthesis, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.Y.; Rose, D.E.; Ganz, D.A.; Giannitrapani, K.F.; Yano, E.M.; Rubenstein, L.V.; Stockdale, S.E. Elements of the Healthy Work Environment Associated with Lower Primary Care Nurse Burnout. Nurs. Outlook 2020, 68, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisoglou, I.; Yfantis, A.; Tsiouma, E.; Galanis, P. The Work Environment of Haemodialysis Nurses and Its Mediating Role in Burnout. J. Ren. Care 2021, 47, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillero-Sillero, A.; Zabalegui, A. Analysis of the Work Environment and Intention of Perioperative Nurses to Quit Work. Rev. Lat. -Am. Enferm. (RLAE) 2020, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, R.; Ghafourifard, M.; Hassankhani, H.; Dehghannezhad, J. The Association of Work Environments and Nurse-Nurse Collaboration: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. Nurse Media J. Nurs. 2021, 11, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, M.L.; Cordova, P.B.; Weaver, S.H. Exploration of the Meaning of Healthy Work Environment for Nurses. Nurse Lead. 2021, 19, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poghosyan, L.; Stein, J.H.; Liu, J.; Spetz, J.; Osakwe, Z.T.; Martsolf, G. State-Level Scope of Practice Regulations for Nurse Practitioners Impact Work Environments: Six State Investigation. Res. Nurs. Health 2022, 45, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabona, J.F.; van Rooyen, D.; Ham-Baloyi, W. Ten. Best Practice Recommendations for Healthy Work Environments for Nurses: An Integrative Literature Review. Health SA Gesondheid 2022, 27, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moisoglou, I.; Yfantis, A.; Galanis, P.; Pispirigou, A.; Chatzimargaritis, E.; Theoxari, A.; Prezerakos, P. Nurses Work Environment and Patients’ Quality of Care. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2020, 13, 1–108. [Google Scholar]

- Poghosyan, L.; Liu, J.; Perloff, J.; D’Aunno, T.; Cato, K.D.; Friedberg, M.W.; Martsolf, G. Primary Care Nurse Practitioner Work Environments and Hospitalizations and ED Use Among Chronically Ill Medicare Beneficiaries. Med. Care 2022, 60, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halm, M. The Influence of Appropriate Staffing and Healthy Work Environments on Patient and Nurse Outcomes. Am. J. Crit. Care 2019, 28, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, G.F.; Amo-Setién, F.; César, L.C.; Concepción, S.S.; Roberto, M.M.; Jesús, M.M.; Carmen, O.M. Effectiveness of Intervention Programs Aimed at Improving the Nursing Work Environment: A Systematic Review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2023, 71, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sabei, S.D.; Labrague, L.J.; Miner Ross, A.; Karkada, S.; Albashayreh, A.; Al Masroori, F.; Al Hashmi, N. Nursing Work Environment, Turnover Intention, Job Burnout, and Quality of Care: The Moderating Role of Job Satisfaction. J. Nurs. Sch. 2020, 52, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrayyan, M.T. Nurses’ Views on Hospital Organizational Characteristics. Nurs. Forum. 2019, 54, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabakleh, Y.; Zhang, J.P.; Lv, M.; Li, J.; Yang, S.; Swai, J.; Li, H.Y. Burnout and Associated Occupational Stresses among Chinese Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study in Three Hospitals. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graystone, R. Creating the Framework for a Healthy Practice Environment. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2018, 48, 469–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zheng, J.; Liu, K.; You, L. Relationship Between Work Environments, Nurse Outcomes, and Quality of Care in ICUs: Mediating Role of Nursing Care Left Undone. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2019, 34, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, L.; White, J.; Scanlon, K. Nurses’ Perceptions of Their Practice Following a Redesign Initiative. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2020, 44, E12–E24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotzer, A.M.; Arellana, K. Defining an Evidence-Based Work Environment for Nursing in the USA. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 1652–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-García, M.C.; Martos-López, I.M.; Casas-López, G.; Márquez-Hernández, V.V.; Aguilera-Manrique, G.; Gutiérrez-Puertas, L. Exploring the Relationship between Midwives’ Work Environment, Women’s Safety Culture, and Intent to Stay. Women Birth 2023, 36, e10–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsufyani, A.M.; Almalki, K.E.; Alsufyani, Y.M.; Aljuaid, S.M.; Almutairi, A.M.; Alsufyani, B.O.; Alshahrani, A.S.; Baker, O.G.; Aboshaiqah, A. Impact of Work Environment Perceptions and Communication Satisfaction on the Intention to Quit: An Empirical Analysis of Nurses in Saudi Arabia. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Yumeng, C.; Chunfen, Z.; Jinbo, F. Analyzing the Impact of Practice Environment on Nurse Burnout Using Conventional and Multilevel Logistic Regression Models. Workplace Health Saf. 2020, 68, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, G.D.; Zavotsky, K.E. Are Critical Care Nurses More Likely to Leave after a Merger? Nurs. Manag. 2018, 49, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raso, R.; Fitzpatrick, J. How Leadership Matters: Clinical Nurses’ Perceptions of Leader Behaviors Affecting Their Work Environment. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 52, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potrebny, T.; Igland, J.; Espehaug, B.; Ciliska, D.; Graverholt, B. Individual and Organizational Features of a Favorable Work Environment in Nursing Homes: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, O.M.P.L.; Cardoso, M.F.; de Lima Trindade, L.; da Rocha, C.G.; Teles, P.J.F.C.; Pereira, S.; Coimbra, V.; Ribeiro, M.P.; Reis, A.; da Conceição Alves Faria, A.; et al. From the First to the Fourth Critical Period of COVID-19: What Has Changed in Nursing Practice Environments in Hospital Settings? BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, O.M.P.L.; de Lima Trindade, L.; da Rocha, C.G.; Teles, P.J.F.C.; Mendes, M.; Ribeiro, M.P.; de Abreu Pereira, S.C.; da Conceição Alves Faria, A.; da Silva, J.M.A.V.; de Sousa, C.N. Scale for the Environments Evaluation of Professional Nursing Practice—Shortened Version: Psychometric Evaluation. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2024, e13291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donley, J. The Impact of Work Environment on Job Satisfaction: Pre-COVID Research to Inform the Future. Nurse Lead. 2021, 19, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soheili, M.; Taleghani, F.; Jokar, F.; Eghbali-Babadi, M.; Sharifi, M. Oncology Nurses’ Needs Respecting Healthy Work Environment in Iran: A Descriptive Exploratory Study. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 8, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, J.; Jones, N. Improving Healthy Work Environments Through Specialty Nursing Professional Development. J. Radiol. Nurs. 2021, 40, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassahun, C.W.; Abate, A.T.; Tezera, Z.B.; Beshah, D.T.; Agegnehu, C.D.; Getnet, M.A.; Abate, H.K.; Yazew, B.G.; Alemu, M.T. Working Environment of Nurses in Public Referral Hospitals of West Amhara, Ethiopia, 2021. BMC Nurs 2022, 21, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddleston, P.; Gray, J. Describing Nurse Leaders’ and Direct Care Nurses’ Perceptions of a Healthy Work Environment in Acute Care Settings, Part 2. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2016, 46, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sabei, S.D.; AbuAlRub, R.; Labrague, L.J.; Ali Burney, I.; Al-Rawajfah, O. The Impact of Perceived Nurses’ Work Environment, Teamness, and Staffing Levels on Nurse-Reported Adverse Patient Events in Oman. Nurs. Forum 2021, 56, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, A.; Yildirim, A. Evaluation of Nurse Manager Practice Environment. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2021, 14, 1437. [Google Scholar]

- Gensimore, M.M.; Maduro, R.S.; Morgan, M.K.; McGee, G.W.; Zimbro, K.S. The Effect of Nurse Practice Environment on Retention and Quality of Care via Burnout, Work Characteristics, and Resilience: A Moderated Mediation Model. J. Nurs. Adm. 2020, 50, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.P.; Oliveira, R.M.; Gomes, M.S.D.B.; Santiago, J.C.D.S.; Silva, R.C.R.; de Souza, F.L. Professional Practice Environment and Nursing Work Stress in Neonatal Units. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2021, 55, e20200539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alenazy, F.S.; Dettrick, Z.; Keogh, S. The Relationship between Practice Environment, Job Satisfaction and Intention to Leave in Critical Care Nurses. Nurs. Crit. Care 2023, 28, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, B.; Cassidy, L.; Barden, C.; Varn-Davis, N.; Delgado, S.A. National Nurse Work Environments—October 2021: A Status Report. Crit Care Nurse 2022, 42, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, G.; Lucas, P.; Gaspar, F. International Portuguese Nurse Leaders’ Insights for Multicultural Nursing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, C.M.; Zheng, K.; Norful, A.A.; Ghaffari, A.; Liu, J.; Poghosyan, L. Primary Care Practice Environment and Burnout Among Nurse Practitioners. J. Nurse Pract. 2021, 17, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, I.; Hendel, T.; Savitsky, B. Personal Initiative and Work Environment as Predictors of Job Satisfaction among Nurses: Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Zheng, J.; Liu, K.; Baggs, J.G.; Liu, X.; You, L. The Impact of Work Environment on Workplace Violence, Burnout and Work Attitudes for Hospital Nurses: A Structural Equation Modelling Analysis. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Yahyaei, A.; Hewison, A.; Efstathiou, N.; Carrick-Sen, D. Nurses’ Intention to Stay in the Work Environment in Acute Healthcare: A Systematic Review. J. Res. Nurs. 2022, 27, 374–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havaei, F.; Astivia, O.L.O.; MacPhee, M. The Impact of Workplace Violence on Medical-Surgical Nurses’ Health Outcome: A Moderated Mediation Model of Work Environment Conditions and Burnout Using Secondary Data. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 109, 103666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolo Barandino, J.; Platon Soriano, G. Practice Environment and Work-Related Quality of Life among Nurses in a Selected Hospital in Zamboanga, Philippines: A Correlational Study. Nurs. Pract. Today 2019, 6, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paguio, J.T.; Yu, D.S.F.; Su, J.J. Systematic Review of Interventions to Improve Nurses’ Work Environments. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 2471–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarrar, M.; Al-Bsheish, M.; Aldhmadi, B.K.; Albaker, W.; Meri, A.; Dauwed, M.; Minai, M.S. Effect of Practice Environment on Nurse Reported Quality and Patient Safety: The Mediation Role of Person-Centeredness. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincelette, C.; D’Aragon, F.; Stevens, L.M.; Rochefort, C.M. The Characteristics and Factors Associated with Omitted Nursing Care in the Intensive Care Unit: A Cross-Sectional Study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2023, 75, 103343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AONL (American Organization for Nursing Leadership). Elements of a Healthy Practice Environment|AONL. Available online: https://www.aonl.org/elements-healthy-practice-environment (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Abuzied, Y.; Al-Amer, R.; Abuzaid, M.; Somduth, S. The Magnet Recognition Program and Quality Improvement in Nursing. Glob. J. Qual. Saf. Healthc. 2022, 5, 106–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. The International Year of the Nurse and the Midwife Taking Stock of Outcomes and Commitments; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/375009/9789240081925-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 5 February 2024).

| Database (Host) | Search String | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Medline (PubMed) | ((“workplace” [MeSH Terms] OR “work environment” [Title/Abstract] OR “work setting” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“healthy” [Title/Abstract] OR “favorable” [Title/Abstract] OR “positive work environment” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“nursing” [MeSH Terms] OR “nurs*” [Title/Abstract] OR “nursing staff” [MeSH Terms] OR “nurses” [MeSH Terms] OR “nursing practice” [Title/Abstract])) | 636 |

| CINAHL Complete (EBSCO) | ((AB (nurs* OR nursing practice) OR (MH “nursing care”) OR (MH “staff nurses”) OR (MM “nurses”)) AND (AB (work environment OR work setting OR workplace) OR (MM “work environment”) OR (MH “professional practice”)) AND (AB (healthy OR favorable OR positive work environment)) | 997 |

| Mediclatina (EBSCO) | ((AB (nurs* OR nursing practice) OR (MH “nursing care”) OR (MH “staff nurses”) OR (MM “nurses”)) AND (AB (work environment OR work setting OR workplace) OR (MM “work environment”) OR (MH “professional practice”)) AND (AB (healthy OR favorable OR positive work environment)) | 12 |

| RCAAP—Portugal’s Open Access Scientific Repository | (nurs* [description] AND work environment AND (healthy OR favorable OR positive work environment)) Filter: Dissertations and theses | 232 |

| WorldCat | (kw: “nurs*” AND kw: “work environment” AND kw: (“healthy” OR “favorable” OR “positive”)) Filter: Dissertations and theses | 264 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pereira, S.; Ribeiro, M.; Mendes, M.; Ferreira, R.; Santos, E.; Fassarella, C.; Ribeiro, O. Positive Nursing Practice Environment: A Concept Analysis. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 3052-3068. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040222

Pereira S, Ribeiro M, Mendes M, Ferreira R, Santos E, Fassarella C, Ribeiro O. Positive Nursing Practice Environment: A Concept Analysis. Nursing Reports. 2024; 14(4):3052-3068. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040222

Chicago/Turabian StylePereira, Soraia, Marlene Ribeiro, Mariana Mendes, Rosilene Ferreira, Eduardo Santos, Cintia Fassarella, and Olga Ribeiro. 2024. "Positive Nursing Practice Environment: A Concept Analysis" Nursing Reports 14, no. 4: 3052-3068. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040222

APA StylePereira, S., Ribeiro, M., Mendes, M., Ferreira, R., Santos, E., Fassarella, C., & Ribeiro, O. (2024). Positive Nursing Practice Environment: A Concept Analysis. Nursing Reports, 14(4), 3052-3068. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040222