Optimized Continuity of Care Report on Nursing Compliance and Review: A Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Setting

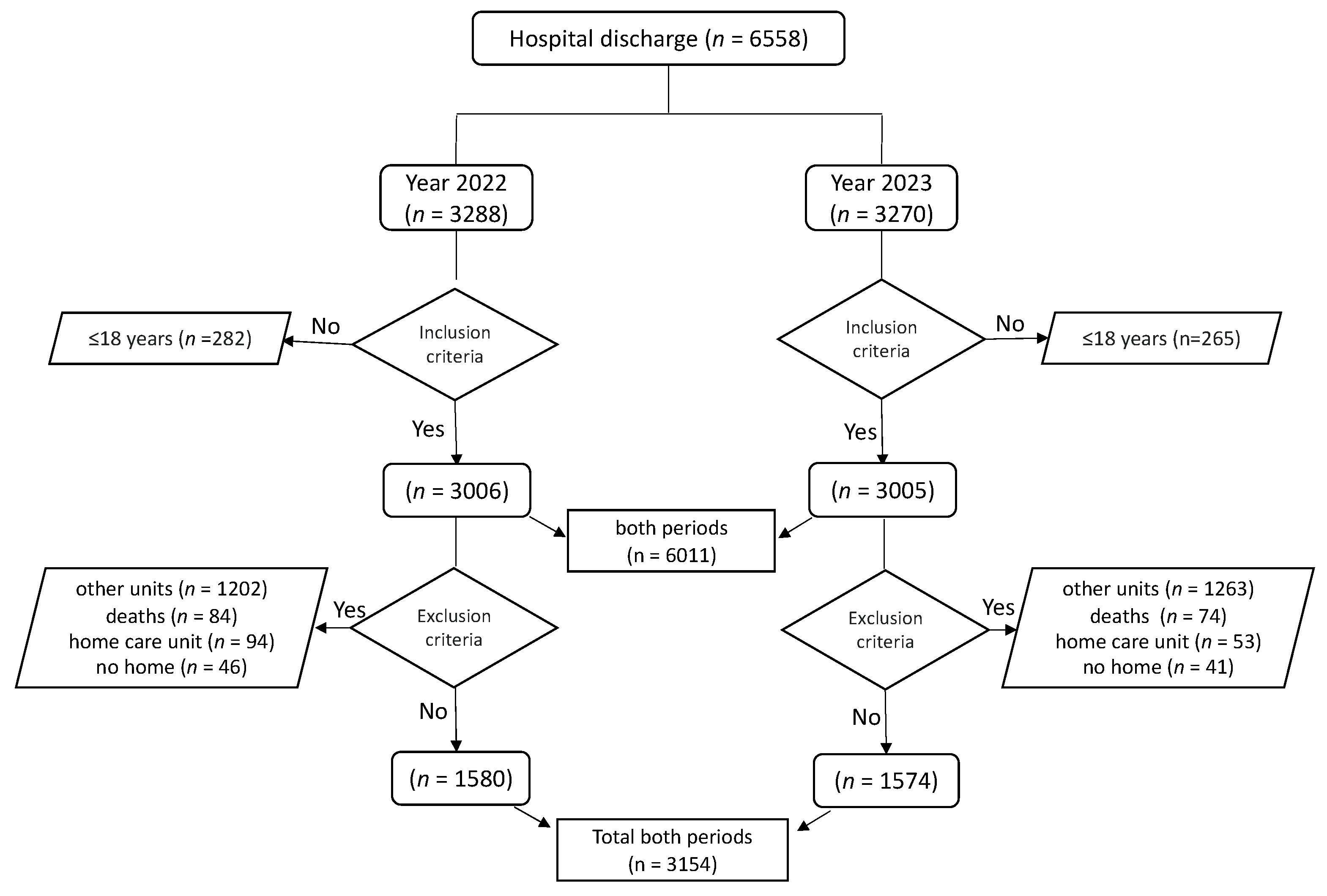

2.2. Participants and Sample

2.3. Description of the Sample Selection Process

2.4. Variables

Characteristics of the Optimization in the CCR

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis Procedures

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Sample

3.2. Completion of the Continuity of Care Report

3.3. Review of the Continuity of Care Report

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Committee on Improving the Quality of Health Care Globally; Board on Global Health; Board on Health Care Services; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Crossing the Global Quality Chasm: Improving Health Care Worldwide; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; p. 25152. ISBN 978-0-309-47789-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lindo, J.; Stennett, R.; Stephenson-Wilson, K.; Barrett, K.A.; Bunnaman, D.; Anderson-Johnson, P.; Waugh-Brown, V.; Wint, Y. An Audit of Nursing Documentation at Three Public Hospitals in Jamaica. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. Off. Publ. Sigma Theta Tau Int. Honor Soc. Nurs. 2016, 48, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, S.E. Calidad de los registros de enfermería en un sector del Hospital Público de la Ciudad de Oberá. Salud Cienc. Tecnol. 2022, 2, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz-Fernández, M.; Martín-Rodríguez, M. Informe de Continuidad de Cuidados al Alta Hospitalaria de Enfermería. Rev. Calid. Asist. 2007, 17, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bellido Castro, M.L. ¿Es el ICC nexo entre AE y AP como continuación de cuidados integrales al paciente quirúrgico en CMA? Inquiet. Rev. Enferm. 2011, 17, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cruzado Álvarez, C.; Bru Torreblanca, A.; González Peral, R.; Aída Otero, S. Valoración del informe de continuidad de cuiadados por enfermeras de atención primaria. Enfermería En Cardiol. 2008, 45, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hellesø, R.; Sorensen, L.; Lorensen, M. Nurses’ Information Management at Patients’ Discharge from Hospital to Home Care. Int. J. Integr. Care 2005, 5, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tizón-Bouza, E.; Camiña Martínez, M.D.; López Rodríguez, M.J.; González-Veiga, A.; Tenreiro Prego, I.; Tizón-Bouza, E.; Camiña Martínez, M.D.; López Rodríguez, M.J.; González-Veiga, A.; Tenreiro Prego, I. Coordinación Interniveles, Importancia Del Informe de Continuidad de Cuidados Enfermería y Satisfacción de Los Pacientes y Familiares Tras La Hospitalización. Ene 2021, 15, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer-García, N.; Roldán-Chicano, M.T.; Rodriguez-Tello, J.; García-López, M.d.M.; Dávila-Martínez, R.; Bueno-García, M.J. Validación del cuestionario CTM-3-modificado sobre satisfacción con la continuidad de cuidados: Un estudio de cohortes. Aquichan 2018, 18, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donabedian, A. Conferencia Magistral. Continuidad y cambio en la búsqueda de la calidad. Salud Pública México 1993, 35, 238–247. [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva Vera, P.; Cambrón Blanco, R.; Dreghiciu, A.M.; Luna Tolosa, M.E.; Úbeda Catalán, C.; Porras Rodrigo, M. Plan de mejora para la continuidad de cuidados del paciente en atención primaria: Informe de alta de enfermería. Rev. Sanit. Investig. 2023, 4, 255. [Google Scholar]

- Cano Arana, A.; Martín Arribas, M.C.; Martínez Piédrola, M.; García Tallés, C.; Hernández Pascual, M.; Roldán Fernández, A. Eficacia de la planificación del alta de enfermería para disminuir los reingresos en mayores de 65 años. Aten. Primaria 2008, 40, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Brown, J.A.; Cooper, A.L.; Albrecht, M.A. Development and Content Validation of the Burden of Documentation for Nurses and Midwives (BurDoNsaM) Survey. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, A.L.; Brown, J.A.; Eccles, S.P.; Cooper, N.; Albrecht, M.A. Is Nursing and Midwifery Clinical Documentation a Burden? An Empirical Study of Perception versus Reality. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 1645–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, J.I.; Duffield, C.; Li, L.; Creswick, N.J. How Much Time Do Nurses Have for Patients? A Longitudinal Study Quantifying Hospital Nurses’ Patterns of Task Time Distribution and Interactions with Health Professionals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2011, 11, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, Y.M. Comparison of Nurses’ Job Satisfaction, Patients’ Satisfaction and Direct Nursing Time According to the Change in Grade of the Nursing Management Fee. J. Korean Crit. Care Nurs. 2017, 10, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dave, P. How Digital Health Is Revolutionizing Healthcare and Contributing to Positive Health Outcomes. J. Drug Delivery Ther. 2024, 14, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abernethy, A.; Adams, L.; Barrett, M.; Bechtel, C.; Brennan, P.; Butte, A.; Faulkner, J.; Fontaine, E.; Friedhoff, S.; Halamka, J.; et al. The Promise of Digital Health: Then, Now, and the Future. NAM Perspect. 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Ríos, M.; Canga Pérez, R.; García Bango, A.; Fernández Fernández, B.; Manjón García, P.; Ferrero Fernández, I.E. Utilidad percibida del informe de continuidad de cuidados de enfermería. RqR Enferm. Comunitaria 2019, 7, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Correa Casado, M. El informe de continuidad de cuidados como herramienta de comunicación entre atención hospitalaria y atención primaria = The continuity of care report inform as a communication tool between hospital and primary care. Rev. Esp. Comun. Salud 2014, 15, 102–111. [Google Scholar]

- Dowding, D.W.; Russell, D.; Onorato, N.; Merrill, J.A. Technology Solutions to Support Care Continuity in Home Care: A Focus Group Study. J. Healthc. Qual. 2018, 40, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumbo Prieto, J.M.; Martínez Ques, Á.A.; Sobrido Prieto, M.; Raña Lama, C.D.; Vázquez Campo, M.; Braña Marcos, B. Implementar evidencias e investigar en implementación: Dos realidades diferentes y prioritarias. Enfermería Clínica 2016, 26, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasperini, B.; Pelusi, G.; Frascati, A.; Sarti, D.; Dolcini, F.; Espinosa, E.; Prospero, E. Predictors of Adverse Outcomes Using a Multidimensional Nursing Assessment in an Italian Community Hospital. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, A.T.G.; da Silva, M.B.; de Abreu Almeida, A. Quality of Nursing Documentation before and after the Hospital Accreditation in a University Hospital. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2016, 24, e2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Llagostera-Reverter, I.; Luna-Aleixos, D.; Valero-Chillerón, M.J.; Martínez-Gonzálbez, R.; Mecho-Montoliu, G.; González-Chordá, V.M. Improving Nursing Assessment in Adult Hospitalization Units: A Secondary Analysis. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 1148–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhu-Zaheya, L.; Al-Maaitah, R.; Bany Hani, S. Quality of Nursing Documentation: Paper-Based Health Records versus Electronic-Based Health Records. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, e578–e589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.K.; McNeill, M. Implementing a Care Plan System in a Community Hospital Electronic Health Record. Comput. Inform. Nurs. CIN 2023, 41, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caleres, G.; Bondesson, Å.; Midlöv, P.; Modig, S. Elderly at Risk in Care Transitions When Discharge Summaries Are Poorly Transferred and Used—A Descriptive Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, R.A.; Lawrence, E.; McCreight, M.; Fehling, K.; Glasgow, R.E.; Rabin, B.A.; Burke, R.E.; Battaglia, C. Perspectives of Clinicians, Staff, and Veterans in Transitioning Veterans from Non-VA Hospitals to Primary Care in a Single VA Healthcare System. J. Hosp. Med. 2020, 15, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Asencio, J.M.; Porcel-Gálvez, A.M.; Oliveros-Valenzuela, R.; Rodríguez-Gómez, S.; Sánchez-Extremera, L.; Serrano-López, F.A.; Aranda-Gallardo, M.; Canca-Sánchez, J.C.; Barrientos-Trigo, S. Design and Validation of the INICIARE Instrument, for the Assessment of Dependency Level in Acutely Ill Hospitalised Patients. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 761–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, V. The Nature of Nursing a Definition and Its Implications for Practice, Research, and Education; Macmillan: London, UK, 1966; ISBN 978-0-02-353520-8. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Arnedo, J.M.; Orgiler Uranga, P.E.; de Haro Marín, S. Informes de alta de enfermería de cuidados intensivos en España: Situación actual y análisis. Enferm. Intensiv. 2005, 16, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palese, A.; Marini, E.; Guarnier, A.; Barelli, P.; Zambiasi, P.; Allegrini, E.; Bazoli, L.; Casson, P.; Marin, M.; Padovan, M.; et al. Overcoming Redundancies in Bedside Nursing Assessments by Validating a Parsimonious Meta-Tool: Findings from a Methodological Exercise Study. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2016, 22, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna-Aleixos, D.; Llagostera-Reverter, I.; Castelló-Benavent, X.; Aquilué-Ballarín, M.; Mecho-Montoliu, G.; Cervera-Gasch, Á.; Valero-Chillerón, M.J.; Mena-Tudela, D.; Andreu-Pejó, L.; Martínez-Gonzálbez, R.; et al. Development and Validation of a Meta-Instrument for Nursing Assessment in Adult Hospitalization Units (VALENF Instrument) (Part I). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykkänen, M.; Miettinen, M.; Saranto, K. Standardized Nursing Documentation Supports Evidence-Based Nursing Management. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2016, 225, 466–470. [Google Scholar]

- Humphries, C.; Jaganathan, S.; Panniyammakal, J.; Singh, S.; Goenka, S.; Dorairaj, P.; Gill, P.; Greenfield, S.; Lilford, R.; Manaseki-Holland, S. Investigating clinical handover and healthcare communication for outpatients with chronic disease in India: A mixed-methods study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iula, A.; Ialungo, C.; de Waure, C.; Raponi, M.; Burgazzoli, M.; Zega, M.; Galletti, C.; Damiani, G. Quality of Care: Ecological Study for the Evaluation of Completeness and Accuracy in Nursing Assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, S.; Alshmari, M.; Latif, K.; Ahmad, H.F. A Granular Ontology Model for Maternal and Child Health Information System. J. Healthc. Eng. 2017, 2017, e9519321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag, H.-G. Quality Management: A Basic Instrument in Healthcare Systems. Biomed. Istraživanja 2020, 12, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, C.J.; Ezechi, O.C.; Folahanmi, A. Assessing patient safety culture among healthcare professionals in Ibadan South-west region of Oyo State, Nigeria. J. Patient Saf. Risk Manag. 2023, 28, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saumalina; Marlina; Usman, S. The Related Factors to Nursing Documentation at General Hospital Dr. Zainoel Abidin Banda Aceh. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. 2023, 15, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søndergaard, S.F.; Lorentzen, V.; Sørensen, E.E.; Frederiksen, K. Danish Perioperative Nurses’ Documentation: A Complex, Multifaceted Practice Connected with Unit Culture and Nursing Leadership. AORN J. 2017, 106, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, M.; Saleh, A.; Rachmawaty, R. The Influence of Supervision on the Performance of Associate Nurse in Hospitals: A Literature Review. J. Nurs. Pract. 2019, 2, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Facchinetti, G.; Ianni, A.; Piredda, M.; Marchetti, A.; D’Angelo, D.; Dhurata, I.; Matarese, M.; De Marinis, M.G. Discharge of Older Patients with Chronic Diseases: What Nurses Do and What They Record. An Observational Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 1719–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracher, M.; Steward, K.; Wallis, K.; May, C.R.; Aburrow, A.; Murphy, J. Implementing Professional Behaviour Change in Teams under Pressure: Results from Phase One of a Prospective Process Evaluation (the Implementing Nutrition Screening in Community Care for Older People (INSCCOPe) Project). BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afrizal, S.H.; Hidayanto, A.N.; Handayani, P.W.; Budiharsana, M.; Eryando, T. Narrative Review for Exploring Barriers to Readiness of Electronic Health Record Implementation in Primary Health Care. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2019, 25, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrone, P. Principios de la comunicación efectiva en una organización de salud. Rev. Colomb. Cir. 2021, 36, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, T.; Ikeda, M.; Umemoto, K. Enhancement of Healthcare Quality Using Clinical-pathways Activities. VINE 2011, 41, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.H. Nurses’ Knowledge and Beliefs about Continence Interventions in Long-Term Care. J. Adv. Nurs. 1995, 21, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamedsharif, A.; Gemperli, A. Healthcare Interventions to Improve Transitions from Hospital to Home in Low-Income Countries: A Scoping Review of Systematic Reviews. Int. J. Integr. Care 2023, 23, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Effect of Electronic Medical Record Quality on Nurses’ Perceived Usefulness and Ease of Use. CIN Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2022, 40, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuti, S. La Valutazione della Performance in Sanità; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2008; ISBN 978-88-15-12427-2. [Google Scholar]

- Radojicic, M.; Jeremic, V.; Savic, G. Going beyond Health Efficiency: What Really Matters? Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2020, 35, 318–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | 2022 | 2023 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m(ds) 1 | m(ds) 1 | p | ||

| Age | 66.17 (17.77) | 65.25 (18.44) | 0.198 2 | |

| %(n) 3 | %(n) 3 | |||

| Sex | Male | 52.7 (832) | 50.4 (793) | 0.201 4 |

| Female | 47.3 (748) | 49.6 (781) | ||

| Process type | Medical | 55.0 (869) | 57.2 (900) | 0.218 4 |

| Surgical | 45.0 (711) | 42.8 (674) | ||

| Admission type | Emergency | 70.9 (1121) | 71.6 (1127) | 0.686 4 |

| Scheduled | 29.1 (459) | 28.4 (447) | ||

| 2022 | 2023 | TOTAL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization Units | Total | CCR | Total | CCR | ||

| n 1 | %(n) 2 | n 1 | %(n) 2 | p 3 | %(n) 2 | |

| Traumatology | 379 | 92.6 (351) | 349 | 71.6 (250) | <0.001 | 82.6 (601) |

| Surgery/Gynecology | 363 | 53.7 (195) | 346 | 63.0 (218) | 0.012 | 58.3 (413) |

| Cardiology/Digestive | 359 | 54.6 (196) | 368 | 66.6 (245) | <0.001 | 60.7 (441) |

| Surgery | 342 | 70.8 (242) | 292 | 63.4 (185) | 0.048 | 67.4 (427) |

| Internal Medicine | 137 | 89.1 (122) | 219 | 79.9 (175) | 0.024 | 83.4 (297) |

| Process type | ||||||

| Medical | 869 | 67.2 (584) | 900 | 69.7 (627) | 0.265 | 68.5 (1211) |

| Surgical | 711 | 73.4 (522) | 674 | 66.2 (446) | 0.003 | 69.9 (968) |

| Admission type | ||||||

| Emergency | 1121 | 69.8 (782) | 1127 | 70.1 (790) | 0.861 | 69.9 (1572) |

| Scheduled | 459 | 70.6 (324) | 447 | 63.3 (283) | 0.02 | 67.0 (607) |

| Total | 1580 | 70.0 (1106) | 1574 | 68.2 (1073) | 0.266 | 69.1 (2179) |

| 2022 | 2023 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization Units | Total | CCR | Total | CCR | |

| n 1 | %(n) 2 | n 1 | %(n) 2 | p 3 | |

| Traumatology | 351 | 6.6 (23) | 250 | 30.4 (76) | <0.001 |

| Surgery/Gynecology | 195 | 4.6 (9) | 218 | 29.8 (65) | <0.001 |

| Cardiology/Digestive | 196 | 2 (4) | 245 | 33.1 (81) | <0.001 |

| Surgery | 242 | 4.1 (10) | 185 | 29.7 (55) | <0.001 |

| Internal Medicine | 122 | 2.5 (3) | 175 | 28.6 (50) | <0.001 |

| Process type | |||||

| Medical | 584 | 3.3 (19) | 627 | 32.1 (201) | <0.001 |

| Surgical | 522 | 5.7 (30) | 446 | 28.3 (126) | <0.001 |

| Admission type | |||||

| Emergency | 782 | 3.7 (29) | 790 | 31.4 (248) | <0.001 |

| Scheduled | 324 | 6.2 (20) | 283 | 27.9 (79) | <0.001 |

| Total | 1106 | 4.4 (49) | 1073 | 30.5 (327) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luna-Aleixos, D.; Francisco-Montesó, L.; López-Negre, M.; Blasco-Peris, D.; Llagostera-Reverter, I.; Valero-Chillerón, M.J.; Cervera-Pitarch, A.D.; Gallego-Clemente, A.; Leal-Costa, C.; González-Chordá, V.M. Optimized Continuity of Care Report on Nursing Compliance and Review: A Retrospective Study. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 2095-2106. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030156

Luna-Aleixos D, Francisco-Montesó L, López-Negre M, Blasco-Peris D, Llagostera-Reverter I, Valero-Chillerón MJ, Cervera-Pitarch AD, Gallego-Clemente A, Leal-Costa C, González-Chordá VM. Optimized Continuity of Care Report on Nursing Compliance and Review: A Retrospective Study. Nursing Reports. 2024; 14(3):2095-2106. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030156

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuna-Aleixos, David, Lorena Francisco-Montesó, Marta López-Negre, Débora Blasco-Peris, Irene Llagostera-Reverter, María Jesús Valero-Chillerón, Ana Dolores Cervera-Pitarch, Andreu Gallego-Clemente, César Leal-Costa, and Víctor M. González-Chordá. 2024. "Optimized Continuity of Care Report on Nursing Compliance and Review: A Retrospective Study" Nursing Reports 14, no. 3: 2095-2106. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030156

APA StyleLuna-Aleixos, D., Francisco-Montesó, L., López-Negre, M., Blasco-Peris, D., Llagostera-Reverter, I., Valero-Chillerón, M. J., Cervera-Pitarch, A. D., Gallego-Clemente, A., Leal-Costa, C., & González-Chordá, V. M. (2024). Optimized Continuity of Care Report on Nursing Compliance and Review: A Retrospective Study. Nursing Reports, 14(3), 2095-2106. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030156