Predisposing Factors to Medication Errors by Nurses and Prevention Strategies: A Scoping Review of Recent Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Research Question

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Search Strategy

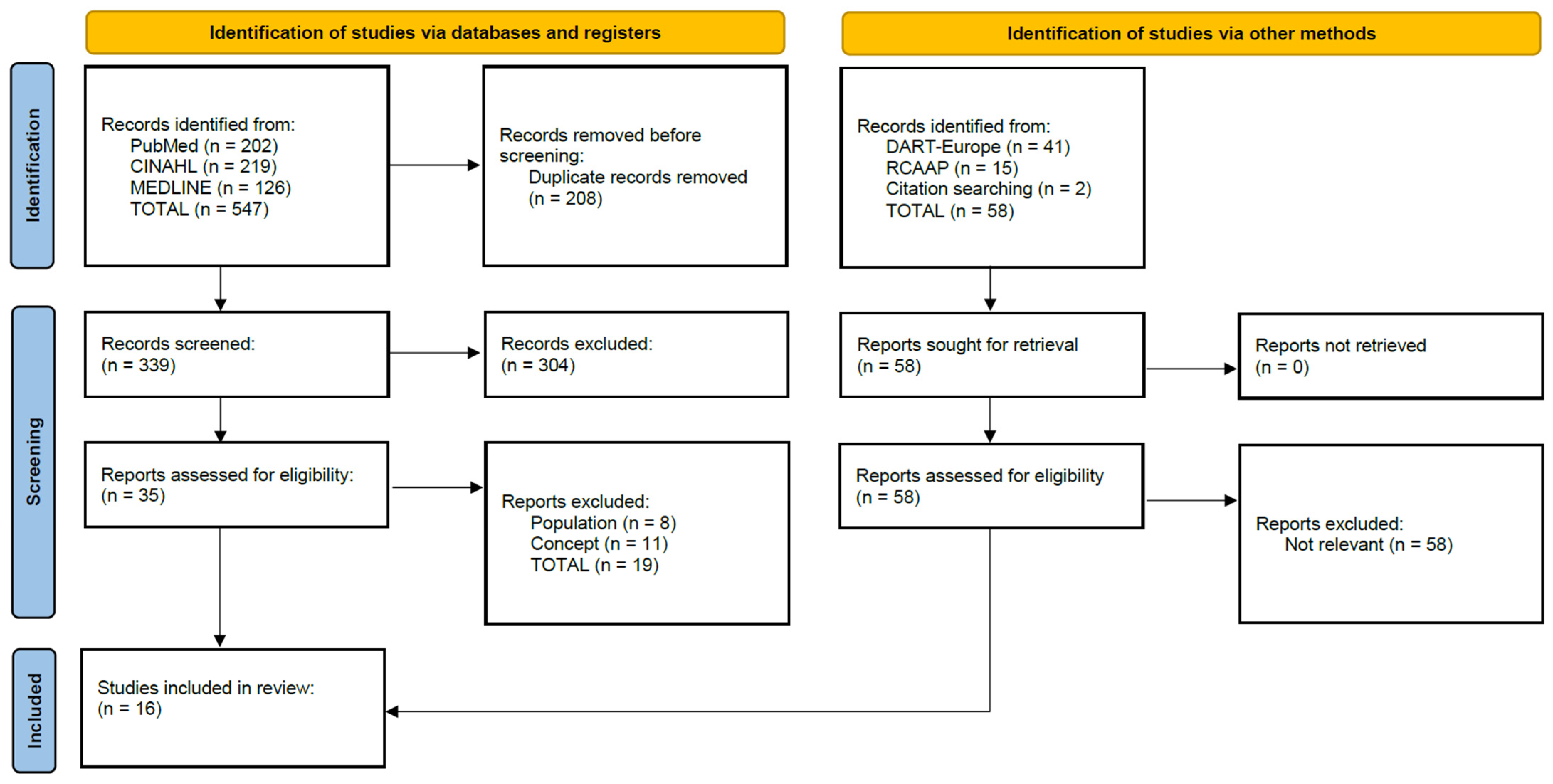

2.5. Study Selection

2.6. Data Extraction

2.7. Data Synthesis and Reporting

3. Results

3.1. Characterisation of the Reported Studies

3.2. Types of Errors

3.3. Factors Predisposing to Error

3.3.1. Organizational Factors

3.3.2. Knowledge and Training

3.3.3. System-Related Factors

3.3.4. Personal Factors

3.3.5. Factors Related to Procedures

3.4. Consequences of Error

3.5. Error Mitigation Interventions

3.5.1. Educational Intervention

3.5.2. Verification and Security Methods

3.5.3. Organizational and Functional Changes

3.5.4. Error Notification

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Nursing Practice

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mohsenpour, M.; Hosseini, M.; Abbaszadeh, A.; Shahboulaghi, F.; Khankeh, H. Nursing error: An integrated review of the literature. Indian J. Med. Ethics 2017, 2, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alblowi, F.; Alaidi, H.; Dakhilallah, H.; Alamrani, A. Nurses’ perspectives on causes and barriers to reporting medication administration errors. Health Sci. J. 2021, 15, 884. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, E.; Pires, D.; Padilha, M.; Martins, M. Nursing errors: A study of the current literature. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2017, 26, e01400016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Forte, E.; Pires, D.; Schneider, D.; Padilha, M.; Ribeiro, O.; Martins, M. O desfecho do erro de enfermagem como atrativo para a mídia. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2021, 30, e20190168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Direção Geral da Saúde. Processo de Gestão da Medicação. Orientação no 014/2015 de 17/12/2015; Ministério da Saúde: Lisbon, Portugal, 2015; Available online: https://www.dgs.pt/directrizes-da-dgs/orientacoes-e-circulares-informativas/orientacao-n-0142015-de-17122015-pdf.aspx (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Smeulers, M.; Verweij, L.; Maaskant, J.; de Boer, M.; Krediet, C.; Nieveen van Dijkum, E.; Vermeulen, H. Quality indicators for safe medication preparation and administration: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezena, R.; Oliveira, F.; Oliveira, L. Erros de medicação e implicações na assistência de enfermagem. Cuid. Enferm. 2021, 15, 274–280. [Google Scholar]

- Hines, S.; Kynoch, K.; Khalil, H. Effectiveness of interventions to prevent medication errors: An umbrella systematic review protocol. JBI Evid. Synth. 2018, 16, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmanpour, K.; Nemati, S.; Lantta, T.; Ghanei Gheshlagh, R.; Valiee, S. Development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of a nursing error tool in critical care units. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2021, 67, 103079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrabadi, A.; Peyrovi, H.; Valiee, S. Nurses’ error management in critical care units: A qualitative study. Crit. Care Nurs. Q. 2017, 40, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghezeljeh, T.; Farahani, M.; Ladani, F. Factors affecting nursing error communication in intensive care units: A qualitative study. Nurs. Ethics 2021, 28, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.; Colquhoun, H.; Kastner, M.; Levac, D.; Ng, C.; Sharpe, J.; Wilson, K.; et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, M.; Adelson, P.; Peters, M.; Steen, M. Probiotics and human lactational mastitis: A scoping review. Women Birth 2020, 33, e483–e491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, F.; Furtado, L.; Mendonça, N.; Soares, H.; Duarte, H.; Costeira, C.; Santos, C.; Sousa, J.P. Interventions to minimize medication error by nurses in intensive care: A scoping review protocol. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 1040–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reus-Smit, C. The concept of intervention. Rev. Int. Stud. 2013, 39, 1057–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fixsen, D.; Naoom, S.; Blasé, K.; Friedman, R.; Wallace, F. Implementation Research: A Synthesis of the Literature; University of South Florida: Tampa, FL, USA, 2005; Available online: https://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/sites/nirn.fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/NIRN-MonographFull-01-2005.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Moir, T. Why is implementation science important for intervention design and evaluation within educational settings? Front. Educ. 2018, 3, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, D.; Heath, W. The National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention: Promoting patient safety and quality through innovation and leadership. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2008, 34, 700–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention. Taxonomy of Medication Errors; National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention: Villa Park, IL, USA, 2001; Available online: https://www.nccmerp.org/sites/default/files/taxonomy2001-07-31.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Al Meslamani, A. Medication errors during a pandemic: What have we learnt? Expert. Opin. Drug Saf. 2023, 22, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Khalil, H.; Larsen, P.; Marnie, C.; Pollock, D.; Tricco, A.C.; Munn, Z. Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols. JBI Evid. Synth. 2022, 20, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Marnie, C.; Colquhoun, H.; Garritty, C.; Hempel, S.; Horsley, T.; Langlois, E.V.; Lillie, E.; O’brien, K.K.; Tunçalp, Ö.; et al. Scoping reviews: Reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeding, J.; Welch, S.; Whittam, S.; Buscher, H.; Burrows, F.; Frost, C.; Jonkman, M.; Mathews, N.; Wong, K.S.; Wong, A. Medication Error Minimization Scheme (MEMS) in an adult tertiary intensive care unit (ICU) 2009–2011. Aust. Crit. Care 2013, 26, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santomauro, C.; Powell, M.; Davis, C.; Liu, D.; Aitken, L.; Sanderson, P. Interruptions to Intensive Care Nurses and Clinical Errors and Procedural Failures: A Controlled Study of Causal Connection. J. Patient Saf. 2018, 17, e1433–e1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracia, J.; Serrano, R.; Garrido, J. Medication errors and drug knowledge gaps among critical-care nurses: A mixed multi-method study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 640. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia, J.; Sanz, Á.; Serrano, R.; Garrido, J. Medication errors and risk areas in a critical care unit. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 77, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoit, E.; Eckert, P.; Theytaz, C.; Joris-Frasseren, M.; Faouzi, M.; Beney, J. Streamlining the medication process improves safety in the intensive care unit. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2012, 56, 966–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durham, M.; Suhayda, R.; Normand, P.; Jankiewicz, A.; Fogg, L. Reducing Medication Administration Errors in Acute and Critical Care: Multifaceted Pilot Program Targeting RN Awareness and Behaviors. J. Nurs. Adm. 2016, 46, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.; Dantas, A.; Diniz, K.; Barros, K.; Fonsêca, C.; Oliveira, A. Knowledge of the nursing team about the rights of medication in intensive care units. Rev. Enferm. UFPE Line 2014, 8, 1666–1671. [Google Scholar]

- Di Muzio, M.; De Vito, C.; Tartaglini, D.; Villari, P. Knowledge, behaviours, training and attitudes of nurses during preparation and administration of intravenous medications in intensive care units (ICU). A multicenter Italian study. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2017, 38, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Chen, J.; Zheng, S.; Wang, H.; He, X. Reduce medication errors in tube feeding administration by establishing administration standards and standardizing operation procedures. Drugs Ther. Perspect. 2020, 36, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Said, M.; Rahman, R.; Taha, N. The effect of education intervention on parenteral medication preparation and administration among nurses in a general intensive care unit. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2017, 47, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltaybani, S.; Abdelwareth, M.; Abou-Zeid, N.; Ahmed, N. Recommendations to prevent nursing errors: Content analysis of semi-structured interviews with intensive care unit nurses in a developing country. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek, V.; Solevåg, A.; Solberg, M. ICU nurses’ experiences of medication double-checking: A qualitative study. Nord. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 42, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, M. Strategies for Improving Documentation of Medication Overrides. JIN 2018, 3, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Suclupe, S.; Martinez-Zapata, M.; Mancebo, J.; Font-Vaquer, A.; Castillo-Masa, A.; Viñolas, I.; Morán, I.; Robleda, G. Medication errors in prescription and administration in critically ill patients. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 1192–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Reale, C.; Slagle, J.; Anders, S.; Shotwell, M.; Dresselhaus, T.; Weinger, M.B. Facilitated Nurse Medication-Related Event Reporting to Improve Medication Management Quality and Safety in Intensive Care Units. Nurs. Res. 2017, 66, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasinazari, M.; Zareh-Toranposhti, S.; Hassani, A.; Sistanizad, M.; Azizian, H.; Panahi, Y. The effect of information provision on reduction of errors in intravenous drug preparation and administration by nurses in ICU and surgical wards. Acta Med. Iran. 2012, 50, 771–777. [Google Scholar]

- Sahli, A.; Ahmed, M.; Alshammer, A.; Hakami, M.; Hazazi, I.; Alqasem, M.; Alqasem, S.D.; Althiyabi, F.S.B.; Alharbi, F.N.; Haloosh, T.A. A systematized review of nurses’ perceptions of medication errors contributing factors in developing countries. Eur. J. Med. Health Sci. 2021, 3, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Tidman, D. Causes of Medication Error in Nursing. J. Med. Res. Health Sci. 2022, 5, 1753–1764. [Google Scholar]

- Alrabadi, N.; Shawagfeh, S.; Haddad, R.; Mukattash, T.; Abuhammad, S.; Al-rabadi, D.; Abu Farha, R.; AlRabadi, S.; Al-Faouri, I. Medication errors: A focus on nursing practice. J. Pharm. Health Serv. Res. 2021, 12, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Muzio, M.; Dionisi, S.; Di Simone, E.; Cianfrocca, C.; Di Muzio, F.; Fabbian, F.; Barbiero, G.; Tartaglini, D.; Giannetta, N. Can nurses’ shift work jeopardize the patient safety? A systematic review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 4507–4519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kahriman, İ.; Öztürk, H. Evaluating medical errors made by nurses during their diagnosis, treatment and care practices. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 2884–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheu, S.; Wei, I.; Chen, C.; Yu, S.; Tang, F. Using snowball sampling method with nurses to understand medication administration errors. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahrokhi, A.; Ebrahimpour, F.; Ghodousi, A. Factors effective on medication errors: A nursing view. J. Res. Pharm. Pract. 2013, 2, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alandajani, A.; Khalid, B.; Ng, Y.; Banakhar, M. Knowledge and attitudes regarding medication errors among nurses: A cross-sectional study in major jeddah hospitals. Nurs. Rep. 2022, 12, 1023–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eltaybani, S.; Mohamed, N.; Abdelwareth, M. Nature of nursing errors and their contributing factors in intensive care units. Nurs. Crit. Care 2018, 24, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Worafi, Y. Chapter 6—Medication errors. In Drug Safety in Developing Countries; Al-Worafi, Y., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Amrollahi, M.; Khanjani, N.; Raadabadi, M.; Hosseinabadi, M.; Mostafaee, M.; Samaei, S. Nurses’ perspectives on the reasons behind medication errors and the barriers to error reporting. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2017, 6, 132–136. [Google Scholar]

- Jember, A.; Hailu, M.; Messele, A.; Demeke, T.; Hassen, M. Proportion of medication error reporting and associated factors among nurses: A cross sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2018, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search No. | Search Terms and Expressions | Results |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | MH “Nurses” OR TI nurs* OR AB nurs* | 549,244 |

| S2 | MH “Physicians” OR MH “Students+” OR MH “Nursing Assistants” OR TI physician* OR AB physician* OR TI student* OR AB student* OR TI “nursing assistant*” OR AB “nursing assistant*” OR TI “nursing student*” OR AB “nursing student*” OR TI “medical student*” OR AB “medical student*” OR TI undergraduate OR AB undergraduate OR TI “nursing aide*” OR AB “nursing aide*” OR TI “nursing assistant*” OR AB “nursing assistant*” | 943,938 |

| S3 | S1 NOT S2 | 454,611 |

| S4 | MH “Treatment Errors” OR MH “Medication Errors” OR MH “Health Care Errors” OR TI “nursing error*” OR AB “nursing error*” OR TI “medical error*” OR AB “medical error*” OR TI “medication error*” OR AB “medication error*” OR TI “medication administration error*” OR AB “medication administration error*” OR TI “medication preparation error*” OR AB “medication preparation error*” | 2763 |

| S5 | MH “Intensive Care Units” OR MH “Respiratory Care Units” OR MH “Coronary Care Units” OR TI “intensive medical care*” OR AB “intensive medical care*” OR TI “intensive care*” OR AB “intensive care*” OR TI ICU OR AB ICU OR TI “care, intensive” OR AB “care, intensive” OR TI “intensive care unit*” OR AB “intensive care unit*” OR TI “intensive care medicine” OR AB “intensive care medicine” OR TI “respiratory care unit*” OR AB “respiratory care unit*” OR TI “coronary care unit*” OR AB “coronary care unit*” | 245,845 |

| S6 | MH “Intensive Care Units, Pediatric” OR MH “Intensive Care Units, Neonatal” OR TI “intensive care units, pediatric” OR AB “intensive care units, pediatric” OR TI “intensive care units, neonatal” OR AB “intensive care units, neonatal” | 26,934 |

| S7 | S5 NOT S6 | 218,911 |

| S8 | S3 AND S4 AND S7 | 198 |

| S9 | S3 AND S4 AND S7 from 2012–2023 | 126 |

| Dimension | Category | Subcategory | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Types of errors | Preparation errors | Incorrect labelling | [27] |

| Expired infusion | [27,28] | ||

| Dilution errors | [29,30] | ||

| Administration errors | Omission | [28,29,31,32] | |

| Non-interruption | [31] | ||

| Wrong frequency | [29,31] | ||

| Incorrect dosage | [27,29,31,33,34,35] | ||

| Incorrect speed of administration | [27,29,30,31,35,36] | ||

| Incorrect route | [29,31] | ||

| Incorrect medication | [31,37] | ||

| Drug incompatibility | [27,29,35] | ||

| Timetable error | [29,33,38] | ||

| Non-authorised/prescribed administration | [32] | ||

| Double administration | [39] | ||

| Non-aseptic technique | [28,36] | ||

| Interruption during administration | [40] | ||

| Inadequate handling of the therapeutic form | [30,35] | ||

| Documentation errors | Transcription failures | [29,30,31] | |

| Lack of validation | [27,28] | ||

| Factors predisposing to error | Organisational constraints | Work overload | [27,29,34,37,40,41] |

| Night time | [37,38,40] | ||

| Low number of nurses | [38] | ||

| Information overload | [32] | ||

| Time constraints/Time pressure | [27,32,33] | ||

| Knowledge and training | Lack of knowledge | [27,29,32,33,37] | |

| Level of training | [34] | ||

| Length of professional experience | [34,37] | ||

| System-related factors | Inadequate physical environment | [33,38,41] | |

| Lack of rules regulating documentation | [31] | ||

| Lack of system feedback | [27,32] | ||

| Personal factors | Fatigue | [33] | |

| Distraction | [28,29,40] | ||

| Poor relations with the work environment | [29] | ||

| Procedure-related factors | Manual preparation of drugs | [36] | |

| Transcription faults | [30,31] | ||

| Error mitigation interventions | Educational intervention | Posting of posters | [34,36,39,42] |

| Distribution of pamphlets/information leaflets | [32,34,42] | ||

| Training/sensitization sessions | [27,32,34] | ||

| Feedback sessions | [27] | ||

| Discussion groups | [27,39] | ||

| Online drug safety resources | [27,32] | ||

| Frequent training/simulation training/practical training | [28,34,39] | ||

| Educational videos | [36] | ||

| Memory aids | [36] | ||

| PowerPoint presentations | [36] | ||

| Verification and safety methods | Creation of multifunctional forms | [31] | |

| Use of drug administration checklists | [32] | ||

| Checking laboratory values before administration | [32] | ||

| Contacting the prescriber if in doubt | [32] | ||

| Monitoring vital signs before and after drug administration | [34] | ||

| Reducing the frequency of interruptions | [28] | ||

| Use of protocols | [34,35,39] | ||

| Double-checking drug preparation | [38] | ||

| Organisational and functional changes | Different colors, designs, and labels to identify different drug recipients | [37] | |

| Storing medicines with similar labels in different places | [37] | ||

| Use of drug administration | [37] | ||

| Error reporting | Implementation of an error reporting system | [27,34] | |

| Reporting of medication-related events | [41] | ||

| Error communication | [29] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coelho, F.; Furtado, L.; Mendonça, N.; Soares, H.; Duarte, H.; Costeira, C.; Santos, C.; Sousa, J.P. Predisposing Factors to Medication Errors by Nurses and Prevention Strategies: A Scoping Review of Recent Literature. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 1553-1569. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030117

Coelho F, Furtado L, Mendonça N, Soares H, Duarte H, Costeira C, Santos C, Sousa JP. Predisposing Factors to Medication Errors by Nurses and Prevention Strategies: A Scoping Review of Recent Literature. Nursing Reports. 2024; 14(3):1553-1569. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030117

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoelho, Fábio, Luís Furtado, Natália Mendonça, Hélia Soares, Hugo Duarte, Cristina Costeira, Cátia Santos, and Joana Pereira Sousa. 2024. "Predisposing Factors to Medication Errors by Nurses and Prevention Strategies: A Scoping Review of Recent Literature" Nursing Reports 14, no. 3: 1553-1569. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030117

APA StyleCoelho, F., Furtado, L., Mendonça, N., Soares, H., Duarte, H., Costeira, C., Santos, C., & Sousa, J. P. (2024). Predisposing Factors to Medication Errors by Nurses and Prevention Strategies: A Scoping Review of Recent Literature. Nursing Reports, 14(3), 1553-1569. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030117