Cancer Patients with Chronic Pain and Their Caregivers during COVID-19: A Descriptive Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.2. Research Problem

1.3. Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Participants

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

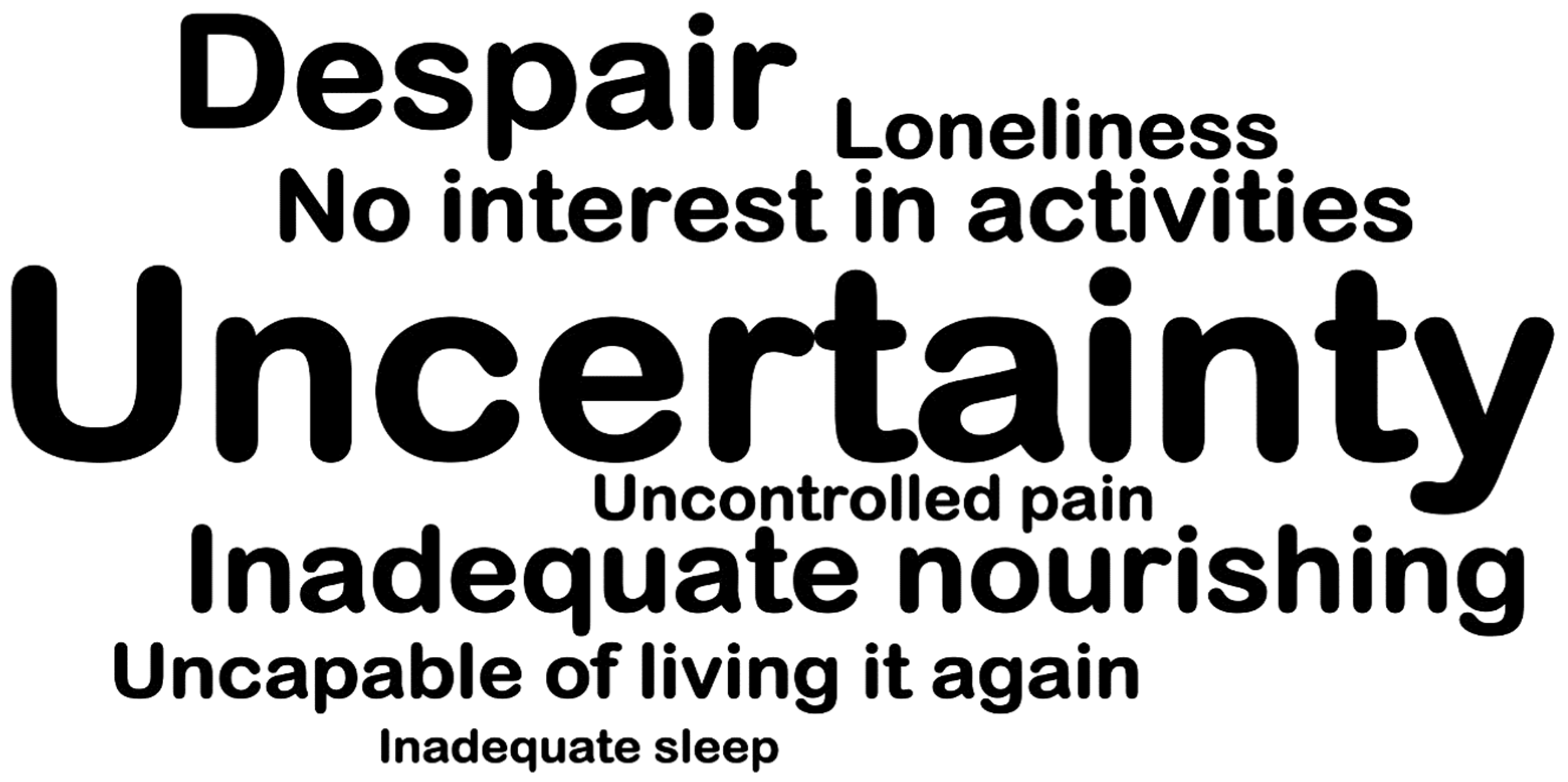

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Depression, Anxiety and Stress Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Item No | Recommendation | Page No | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title and abstract | 1 | (a) Indicate the study’s design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract | 1 |

| (b) Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was performed and what was found | 1 | ||

| Introduction | |||

| Background/rationale | 2 | Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported | 1–2 |

| Objectives | 3 | State specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses | 2 |

| Methods | |||

| Study design | 4 | Present key elements of study design early in the paper | 3 |

| Setting | 5 | Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, exposure, follow-up, and data collection | 3 |

| Participants | 6 | (a) Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of selection of participants. Describe methods of follow-up | 3 |

| (b) For matched studies, give matching criteria and number of exposed and unexposed | |||

| Variables | 7 | Clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers. Give diagnostic criteria, if applicable | 3–4 |

| Data sources/measurement | 8 * | For each variable of interest, give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement). Describe comparability of assessment methods if there is more than one group | 4 |

| Bias | 9 | Describe any efforts to address potential sources of bias | 4 |

| Study size | 10 | Explain how the study size was arrived at | 4–7 |

| Quantitative variables | 11 | Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses. If applicable, describe which groupings were chosen and why | 4–7 |

| Statistical methods | 12 | (a) Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding | |

| (b) Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions | 4–7 | ||

| (c) Explain how missing data were addressed | |||

| (d) If applicable, explain how loss to follow-up was addressed | |||

| (e) Describe any sensitivity analyses | |||

| Results | |||

| Participants | 13 * | (a) Report numbers of individuals at each stage of study—e.g., numbers potentially eligible, examined for eligibility, confirmed eligible, included in the study, completing follow-up, and analyzed | - |

| (b) Give reasons for non-participation at each stage | |||

| (c) Consider use of a flow diagram | |||

| Descriptive data | 14 * | (a) Give characteristics of study participants (e.g., demographic, clinical, social) and information on exposures and potential confounders | 4–7 |

| (b) Indicate number of participants with missing data for each variable of interest | - | ||

| (c) Summarize follow-up time (e.g., average and total amount) | - | ||

| Outcome data | 15 * | Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures over time | 4–7 |

| Main results | 16 | (a) Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates and their precision (e.g., 95% confidence interval). Make clear which confounders were adjusted for and why they were included | |

| (b) Report category boundaries when continuous variables were categorized | 4–7 | ||

| (c) If relevant, consider translating estimates of relative risk into absolute risk for a meaningful time period | |||

| Other analyses | 17 | Report other analyses performed—e.g., analyses of subgroups and interactions, and sensitivity analyses | - |

| Discussion | |||

| Key results | 18 | Summarize key results with reference to study objectives | 7 |

| Limitations | 19 | Discuss limitations of the study, taking into account sources of potential bias or imprecision. Discuss both direction and magnitude of any potential bias | 7 |

| Interpretation | 20 | Give a cautious overall interpretation of results considering objectives, limitations, multiplicity of analyses, results from similar studies, and other relevant evidence | 7 |

| Generalizability | 21 | Discuss the generalizability (external validity) of the study results | 7–8 |

| Other information | |||

| Funding | 22 | Give the source of funding and the role of the funders for the present study and, if applicable, for the original study on which the present article is based | 9 |

References

- Fallon, M.; Giusti, R.; Aielli, F.; Hoskin, P.; Rolke, R.; Sharma, M.; Ripamonti, C.I. Management of cancer pain in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, iv166–iv191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dydyk, A.M.; Grandhe, S. Pain Assessment; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Abahussin, A.A.; West, R.M.; Wong, D.; Ziegler, L.E. PROMs for Pain in Adult Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review of Measurement Properties. Pain Pract. 2018, 19, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhassira, D.; Luporsi, E.; Krakowski, I. Prevalence and incidence of chronic pain with or without neuropathic characteristics in patients with cancer. Pain 2017, 158, 1118–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipponi, C.; Masiero, M.; Pizzoli, S.F.; Grasso, R.; Ferrucci, R.; Pravettoni, G. A Comprehensive Analysis of the Cancer Chronic Pain Experience: A Narrative Review. Cancer Manag. Res. 2022, 14, 2173–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izzo, J.M.; Cunha, A.M.; Cesarino, C.B.; Martins, M.R. The impact of chronic pain on the quality of life and on the functional capacity of cancer patients and their caregivers. Braz. J. Pain 2019, 2, 336–341. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, S.; Hung, J.; Huh, B.K. Impact of COVID-19 on chronic pain patients: A pain physician’s perspective. Pain Manag. 2020, 10, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Cancer Pain Management—New Therapies. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2022, 24, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, R.J.; Mullins, P.M.; Bhattacharyya, N. Prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the United States. Pain 2022, 163, e328–e332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, S.; Lukyanova, V. Chronic Pain Management Guidelines: Time for Review. AANA J. 2022, 90, 169–170. [Google Scholar]

- Brant, J.M. The Assessment and Management of Acute and Chronic Cancer Pain Syndromes. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2022, 38, 151248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katta, M.R.; Valisekka, S.S.; Agarwal, P.; Hameed, M.; Shivam, S.; Kaur, J.; Prasad, S.; Bethineedi, L.D.; Lavu, D.V.; Katamreddy, Y. Non-pharmacological integrative therapies for chronic cancer Pain. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2022, 28, 1859–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadante, S. Cancer Pain Treatment Strategies in Patients with Cancer. Drugs 2022, 82, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paice, J.A. Cancer pain during an epidemic and a pandemic. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2022, 16, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miaskowski, C.; Cleary, J.; Burney, R.; Coyne, P.; Finley, R.; Foster, R.; Grossman, S.; Janjan, N.; Ray, J.; Syrjala, K.; et al. Guideline for the Management of Cancer Pain in Adults and Children; Clinical Practice Guideline; American Pain Society: Glenview, IL, USA, 2005; Available online: https://www.ons.org/node/125711?display=pepnavigator&sort_by=created&items_per_page=50 (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- Panicker, L.; Prasun, M.A.; Stockmann, C.; Simon, J. Evaluation of Chronic, Noncancer Pain Management Initiative in a Multidisciplinary Pain Clinic. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2022, 23, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, H.; Avrit, T.A.; Chan, L.; Burchette, D.M.; Rathore, R. The Benefits of Integrative Medicine in the Management of Chronic Pain: A Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e299693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meints, S.; Edwards, R. Evaluating psychosocial contributions to chronic pain outcomes. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 87, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.P.; Vase, L.; Hooten, W.M. Chronic pain: An update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet 2021, 397, 2082–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugino, F.; de Angelis, V.; Pompili, M.; Martelletti, P. Stigma and Chronic Pain. Pain Ther. 2022, 11, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouvin, A.P.; Attal, N.; Perrot, S. Lifestyle and chronic pain: Double jeopardy? Br. J. Anaesth. 2022, 129, 278–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.O.; Pearson, M.; Smith, M.J.; Fletcher, J.; Irving, L.; Lister, S. Effectiveness of caregiver interventions for people with cancer and non-cancer-related chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Pain 2022, 16, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, N.P. The Self-Management Style of Clients with Chronic Cancer Pain: Influence on the Medication Regimen Management. Ph.D. Thesis, Escola Superior de Enfermagem do Porto (ESEP), Porto, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Higginson, A.; Forgeron, P.; Harrison, D.; Finley, G.A.; Dick, B.D. Moving on: Transition experiences of young adults with chronic Pain. Can. J. Pain 2019, 3, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kianfar, S.; Hundt, A.S.; Hoonakker, P.L.T.; Salek, D.; Tomcavage, J.; Wooldridge, A.R.; Walker, J.; Carayon, P. Understanding care transition notifications for chronically ill patients. IISE Trans. Health Syst. Eng. 2021, 11, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghotbi, T.; Salami, J.; Kalteh, E.A.; Ghelichi-Ghojogh, M. Self-management of patients with chronic diseases during COVID-19: A narrative review. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2021, 62, E814–E821. [Google Scholar]

- Pergolizzi, J.V., Jr.; Magnusson, P.; LeQuang, J.A.; Breve, F.; Paladini, A.; Rekatsina, M.; Yeam, C.T.; Imani, F.; Saltelli, G.; Taylor, R., Jr.; et al. The Current Clinically Relevant Findings on COVID-19 Pandemic. Anesth. Pain Med. 2020, 10, e103819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.C.; Santos, M.; Oliveira-Cardoso, E. Family experiences of cancer patients: Revisiting the literature. Rev. Soc. Psicoter. Analíticas Grupais Estado São Paulo 2019, 20, 140–153. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, E.J.; Goldacre, R.; Spata, E.; Mafham, M.; Finan, P.J.; Shelton, J.; Richards, M.; Spencer, K.; Emberson, J.; Hollings, S.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the detection and management of colorectal cancer in England: A population-based study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais-Ribeiro, J.; Honrado, A.; Leal, I. Contribuição para o estudo da adaptação portuguesa das escalas de Depressão Ansiedade Stress de Lovibond e Lovibond. Psychologica 2004, 36, 235–246. [Google Scholar]

- Evers, A.; Hagemeister, C.; Høstmælingen, A.; Lindley, P.; Muñiz, J.; Sjöberg, A. Efpa Review Model for the Description and Evaluation of Psychological and Educational Tests; Test Review form and Notes for Reviewers Version 42; British Psychological Society’s (BPS): London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Greiner, B.; Tipton, S.; Nelson, B.; Hartwell, M. Cancer screenings during the COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis of public interest trends. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2022, 46, 100766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinori, S.G.F.; Carot-Sans, G.; Cuartero, A.; Valero-Bover, D.; Monfa, R.R.; Garcia, E.; Sust, P.P.; Blanch, J.; Piera-Jiménez, J.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.A. A Web-Based App for Emotional Management During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Platform Development and Retrospective Analysis of its Use Throughout Two Waves of the Outbreak in Spain. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e27402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, E.; Guzman, P.; Mims, M.; Badr, H. Balancing Work and Cancer Care: Challenges Faced by Employed Informal Caregivers. Cancers 2022, 14, 4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Castro, F.J.; Hernández, A.; Blanca, M.J. Life satisfaction and the mediating role of character strengths and gains in informal caregivers. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 29, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokas, C.M.; Hu, F.Y.; Dalton, M.K.; Jarman, M.P.; Bernacki, R.E.; Bader, A.; Rosenthal, R.A.; Cooper, Z. Understanding the role of informal caregivers in postoperative care transitions for older patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.J.; Narendrula, A.; Iyer, S.; Zanotti, K.; Sindhwani, P.; Mossialos, E.; Ekwenna, O. Patient-reported disruptions to cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national cross-sectional study. Cancer Med. 2022, 12, 4773–4785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emerick, T.; Alter, B.; Jarquin, S.; Brancolini, S.; Bernstein, C.; Luong, K.; Morrissey, S.; Wasan, A. Telemedicine for Chronic Pain in the COVID-19 Era and Beyond. Pain Med. 2020, 21, 1743–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasoon, J.; Urits, I.; Viswanath, O.; Kaye, A.D. Pain Management and Telemedicine: A Look at the COVID Experience and Beyond. Health Psychol. Res. 2022, 10, 38012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulchar, R.J.; Chen, K.; Moon, C.; Srinivas, S.; Gupta, A. Telemedicine, safe medication stewardship, and COVID-19: Digital transformation during a global pandemic. J. Interprof. Educ. Pract. 2022, 29, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aapro, M.; Bossi, P.; Dasari, A.; Fallowfield, L.; Gascón, P.; Geller, M.; Jordan, K.; Kim, J.; Martin, K.; Porzig, S. Digital health for optimal supportive care in oncology: Benefits, limits, and future perspectives. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 4589–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrowicz-Campos, E.; Ventura, F. Centralidade na pessoa para uma saúde digital equitativa. In Cadernos de Saude Societal: Transformação Digital e Inclusão na Saúde; Martins, C., Camilo, C., Cardoso, C., Bobrowicz-Campos, E., Ferreira, J., Lima, M., Viegas, R., Leite, F., Eds.; ISCTE: Lisboa, Portugal, 2022; pp. 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Spelten, E.R.; Hardman, R.N.; Pike, K.E.; Yuen, E.Y.; Wilson, C. Best practice in the implementation of telehealth-based supportive cancer care: Using research evidence and discipline-based guidance. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 2682–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchia, M.; Gathier, A.W.; Yapici-Eser, H.; Schmidt, M.V.; de Quervain, D.; van Amelsvoort, T.; Bisson, J.I.; Cryan, J.F.; Howes, O.D.; Pinto, L.; et al. The impact of the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic on stress resilience and mental health: A critical review across waves. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 55, 22–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascella, M.; Miceli, L.; Cutugno, F.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Morabito, A.; Oriente, A.; Massazza, G.; Magni, A.; Marinangeli, F.; Cuomo, A.; et al. A Delphi Consensus Approach for the Management of Chronic Pain during and after the COVID-19 Era. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Hannon, B.L.; Zimmermann, C.; Bruera, E. Improving patient and caregiver outcomes in oncology: Team-based, timely, and targeted palliative care. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 356–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, A.M.; Charalambous, A.; Owen, R.I.; Njodzeka, B.; Oldenmenger, W.H.; Alqudimat, M.R.; So, W.K. Essential oncology nursing care along the cancer continuum. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, e555–e563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patients, n = 30 n (%) | Caregivers, n = 13 n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 21 (70%) | 10 (77%) |

| Male | 9 (30%) | 3 (23%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 1 (3.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Married | 24 (80%) | 13 (100%) |

| Divorced | 4 (13.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Widow | 1 (3.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Educational level | ||

| Basic studies | 23 (76.7%) | 6 (46.1%) |

| Superior studies | 7 (23.3%) | 7 (53.9%) |

| Living area | ||

| Rural | 17 (56.7%) | 7 (53.8%) |

| Urban | 13 (43.4%) | 6 (46.2%) |

| Confined at home | ||

| Yes | 26 (86.7%) | 9 (69.2%) |

| No | 4 (13.3%) | 4 (30.8%) |

| Alone at home | ||

| Yes | 6 (20%) | 0 (0%) |

| No | 24 (80%) | 13 (100%) |

| SOS Pain medication | ||

| Yes | 14 (46.7%) | 6 (46.1%) |

| No | 16 (53.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Not applied | 0 (0%) | 7 (53.8%) |

| Negative Impact from cancelled therapeutic massage | ||

| Yes | 10 (33.3%) | 4 (30.8%) |

| No | 6 (20%) | 1 (7.7%) |

| Not applied | 14 (46.7%) | 8 (61.5%) |

| Contact with Pain Unit | ||

| Yes | 26 (86.7%) | 7 (53.8%) |

| No | 4 (13.3%) | 6 (46.1%) |

| Adequate pain follow-up | ||

| Yes | 26 (86.7%) | 6 (46.1%) |

| No | 1 (3.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Maybe | 3 (10%) | 7 (53.8%) |

| Adequate healthcare follow-up | ||

| Yes | 26 (86.7%) | 6 (46.1%) |

| No | 1 (3.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| I prefer not to respond | 3 (10%) | 7 (53.8%) |

| App as communication strategy | ||

| Yes | 24 (80%) | 11 (84.6%) |

| No | 2 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Maybe | 4 (13.3%) | 2 (15.4%) |

| Strategies | ||

| Frequent telephone calls | 30 (100%) | 13 (100%) |

| Videoconferences | 12 (40%) | 6 (46.2%) |

| Physical approaches (massage; acupuncture) | 21 (70%) | 4 (30.8%) |

| Psychosocial approaches (supportive therapy) | 24 (80%) | 7 (53.8%) |

| Patients (n = 30) | Caregivers (n = 13) | Test U | p | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle Rank | SD | Min | Max | Middle Rank | SD | Min | Max | |||

| Depression | 21.74 | 3.60 | 7 | 23 | 20.96 | 4.39 | 7 | 20 | 181.50 | 0.85 |

| Anxiety | 22.48 | 3.88 | 7 | 22 | 17.42 | 5.23 | 7 | 22 | 131.00 | 0.23 |

| Stress | 21.80 | 3.70 | 7 | 20 | 20.75 | 4.83 | 7 | 22 | 171.00 | 0.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Costeira, C.; Paiva-Santos, F.; Pais, N.; Sousa, A.F.; Paiva, I.; Carvalho, D.H.; Rocha, A.; Ventura, F. Cancer Patients with Chronic Pain and Their Caregivers during COVID-19: A Descriptive Study. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 934-945. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13030082

Costeira C, Paiva-Santos F, Pais N, Sousa AF, Paiva I, Carvalho DH, Rocha A, Ventura F. Cancer Patients with Chronic Pain and Their Caregivers during COVID-19: A Descriptive Study. Nursing Reports. 2023; 13(3):934-945. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13030082

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosteira, Cristina, Filipe Paiva-Santos, Nelson Pais, Ana Filipa Sousa, Ivo Paiva, Dulce Helena Carvalho, Ana Rocha, and Filipa Ventura. 2023. "Cancer Patients with Chronic Pain and Their Caregivers during COVID-19: A Descriptive Study" Nursing Reports 13, no. 3: 934-945. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13030082

APA StyleCosteira, C., Paiva-Santos, F., Pais, N., Sousa, A. F., Paiva, I., Carvalho, D. H., Rocha, A., & Ventura, F. (2023). Cancer Patients with Chronic Pain and Their Caregivers during COVID-19: A Descriptive Study. Nursing Reports, 13(3), 934-945. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13030082