Collective Violence against Health Workers in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Definitions and Scope of the Analysis

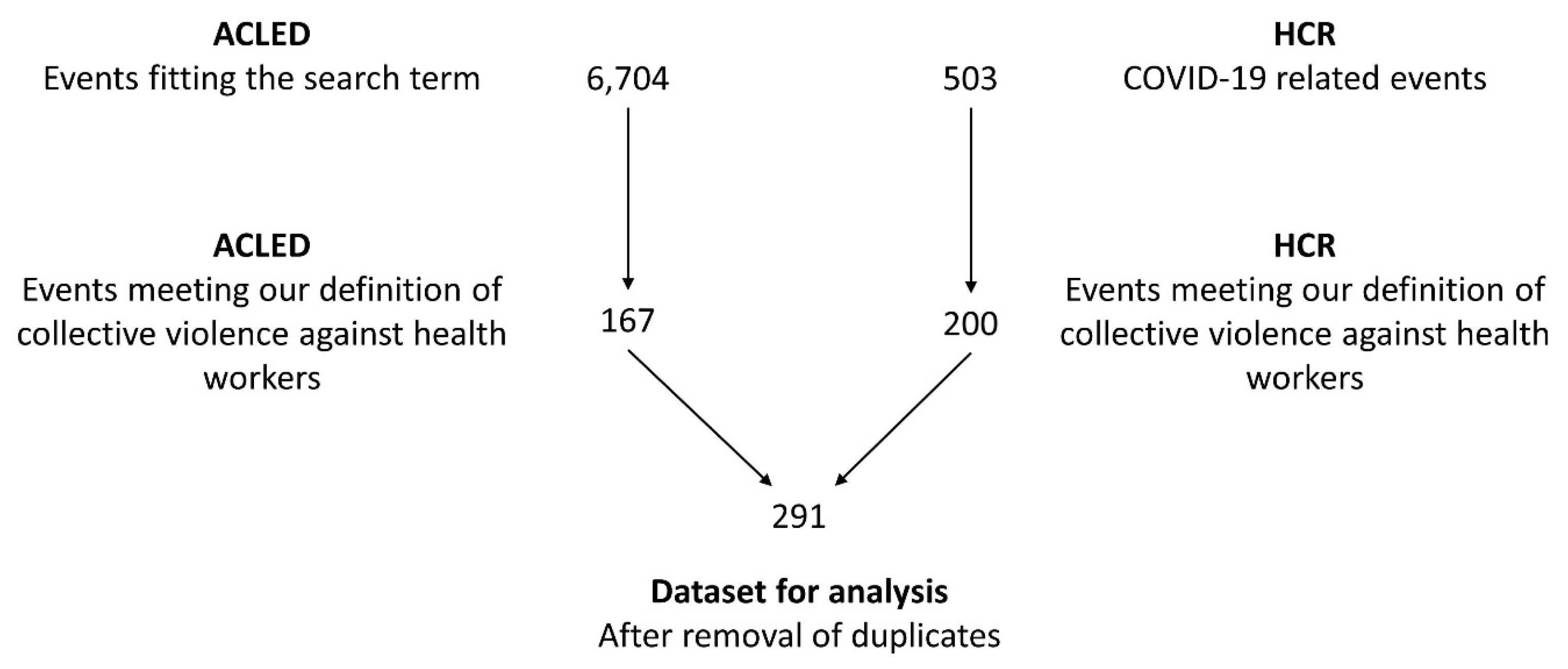

2.2. Sample and Data

2.3. Data Analysis

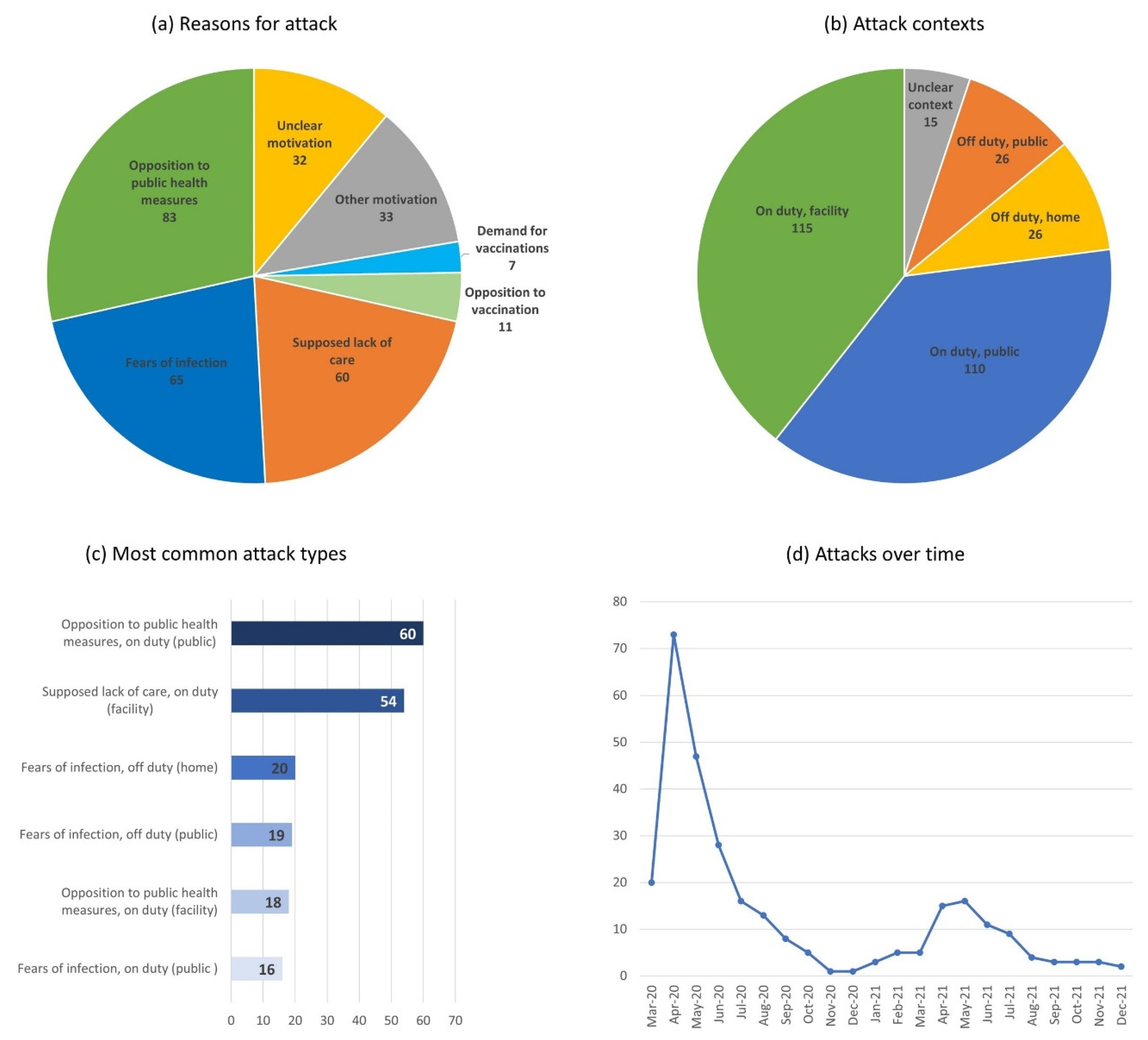

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

References

- WHO. Keep Health Workers Safe to Keep Patients Safe. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/17-09-2020-keep-health-workers-safe-to-keep-patients-safe-who (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- McKay, D.; Heisler, M.; Mishori, R.; Catton, H.; Kloiber, O. Attacks against health-care personnel must stop, especially as the world fights COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1743–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devnani, M. COVID-19 and laws for workplace violence in healthcare. BMJ 2021, 375, n2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipf, A.L.; Polifroni, E.C.; Beck, C.T. The experience of the nurse during the COVID-19 pandemic: A global meta-synthesis in the year of the nurse. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2022, 54, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACLED. Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project. 2022. Available online: www.acleddata.com (accessed on 19 February 2022).

- Insecurity Insight. Attacked and Threatened: Health Care at Risk. 2022. Available online: https://map.insecurityinsight.org/health (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Liu, J.; Gan, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, L.; Dwyer, R.; Lu, K.; Yan, S.; Sampson, O.; Xu, H.; Wang, C.; et al. Prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 76, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, P.E.; Zhou, Z.E.; Che, X.X. Nurse exposure to physical and nonphysical violence, bullying, and sexual harassment: A quantitative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, B.J.; Browne, M.; O’Neill, B.J.; Dealy, M.T.; Clare, D.; O’Meara, P. International survey of violence Against EMS personnel: Physical violence report. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2018, 33, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Z.; Wu, D.; Wang, N.; Hesketh, T.; Sun, K.S.; Li, L.; Zhou, X. Workplace violence and its aftermath in China’s health sector: Implications from a cross-sectional survey across three tiers of the health system. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e031513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, S.; Zeh, A.; Schablon, A.; Kuhnert, S.; Nienhaus, A. Aggression and violence against health care workers in Germany—A cross sectional retrospective survey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraz, S.; Lubna Ansari, B.; Ibrahim, H.; Mirwais, K.; Seemin, J.; Muhammad Naseem, K.; Munir Akhtar, S.; Komal, Z.; Sumera, E.; Iram, Y.; et al. The magnitude and determinants of violence against healthcare workers in Pakistan. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, H. Navigating attacks against health care workers in the COVID-19 era. JAMA 2021, 325, 1822–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafny, H.A.; Beccaria, G. I do not even tell my partner: Nurses’ perceptions of verbal and physical violence against nurses working in a regional hospital. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 3336–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bou-Karroum, L.; El-Harakeh, A.; Kassamany, I.; Ismail, H.; El Arnaout, N.; Charide, R.; Madi, F.; Jamali, S.; Martineau, T.; El-Jardali, F.; et al. Health care workers in conflict and post-conflict settings: Systematic mapping of the evidence. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmichael, J.-L.; Karamouzian, M. Deadly professions: Violent attacks against aid-workers and the health implications for local populations. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2014, 2, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, T.D.; Alcantara, L.; Siddiqi, S.; Barbosu, M.; Sharma, S.; Panko, T.; Pressman, E. Risk of COVID-19-related bullying, harassment and stigma among healthcare workers: An analytical cross-sectional global study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e046620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatti, O.A.; Rauf, H.; Aziz, N.; Martins, R.S.; Khan, J.A. Violence against healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A review of incidents from a lower-middle-income country. Ann. Glob. Health 2021, 87, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L. Covid-19 misinformation sparks threats and violence against doctors in Latin America. BMJ 2020, 370, m3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, S. COVID-19 exacerbates violence against health workers. Lancet 2020, 396, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.Y.; Kim, Y.; McDowell, I.; Wong, S.; Qiu, H.; Wong, I.O.L.; Galea, S.; Leung, G.M. Mental health during and after protests, riots and revolutions: A systematic review. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2020, 54, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eck, K. In data we trust? A comparison of UCDP GED and ACLED conflict event datasets. Coop. Confl. 2012, 47, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raleigh, C.; Linke, A.; Hegre, H.; Karlsen, J. Introducing ACLED: An armed conflict location and event dataset. J. Peace Res. 2010, 47, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, M.; O’Loughlin, B. News, media threats and insecurities. Camb. Rev. Int. Aff. 2009, 22, 667–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Bank Open Data. 2022. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- UNDP. Human Development Index (HDI). 2020. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Marshall, M.G.; Jaggers, K.; Gurr, T.R. Polity V Annual Time-Series, 1800–2018. 2020. Available online: http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html (accessed on 24 September 2019).

- Ritchie, H.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Beltekian, D.; Mathieu, E.; Hasell, J.; Macdonald, B.; Giattino, C.; Roser, M. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). 2022. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- Nelson, R. Tackling violence against health-care workers. Lancet 2014, 383, 1373–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vento, S.; Cainelli, F.; Vallone, A. Violence against healthcare workers: A worldwide phenomenon with serious consequences. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 570459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, S.K. Cholera revolts: A class struggle we may not like. Soc. Hist. 2017, 42, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple, K. ‘Afraid to Be a Nurse’: Health Workers under Attack. 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/27/world/americas/coronavirus-health-workers-attacked.html (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Tsao, S.-F.; Chen, H.; Tisseverasinghe, T.; Yang, Y.; Li, L.; Butt, Z.A. What social media told us in the time of COVID-19: A scoping review. Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, e175–e194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharon, A.A.; Warshawski, S.; Itzhaki, M. Public knowledge, attitudes, and intention to act violently, with regard to violence directed at health care staff. Nurs. Outlook 2020, 68, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollyky, T.J.; Templin, T.; Cohen, M.; Schoder, D.; Dieleman, J.L.; Wigley, S. The relationships between democratic experience, adult health, and cause-specific mortality in 170 countries between 1980 and 2016: An observational analysis. Lancet 2019, 393, 1628–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, L.; Perkiss, S.; Dean, B.A.; Moroney, T. Nursing and the Sustainable Development Goals: A scoping review. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2021, 53, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achen, C.H. Let’s Put Garbage-Can Regressions and Garbage-Can Probits Where They Belong. Confl. Manag. Peace Sci. 2005, 22, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attack Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Opposition to public health measures, on duty (public) | 30 March 2020, Jerusalem, Israel: A group of ultra-orthodox people threw rocks at health workers conducting COVID-19 tests. |

| Supposed lack of care on duty (facility) | 5 April 2021, Vadodara, India: More than 60 people vandalised a hospital and attacked staff members after a woman admitted due to COVID-19 died in the hospital. |

| Fears of infection, off duty (home) | 27 May 2020, Merida, Mexico: A group of people feared a nurse would spread COVID-19 in the neighbourhood and set her car and house on fire. |

| Fears of infection, off-duty (public) | 25 May 2020, unspecified location, Honduras: Several perpetrators threw stones at a nurse on her way back home while accusing her of spreading COVID-19. |

| Opposition to public health measures, on duty (facility) | 3 March 2021, Bovenkarspel, Netherlands: Several perpetrators placed and detonated a pipe bomb outside a COVID-19 testing station. |

| Fears of infection, on duty (public) | 1 March 2021, Zambezi, Zambia: When health workers delivered the body of a man who likely died from COVID-19 for burial, they were attacked by a mob throwing stones at them. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jacobi, D.; Ide, T. Collective Violence against Health Workers in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 902-912. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13020079

Jacobi D, Ide T. Collective Violence against Health Workers in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nursing Reports. 2023; 13(2):902-912. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13020079

Chicago/Turabian StyleJacobi, Davina, and Tobias Ide. 2023. "Collective Violence against Health Workers in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic" Nursing Reports 13, no. 2: 902-912. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13020079

APA StyleJacobi, D., & Ide, T. (2023). Collective Violence against Health Workers in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nursing Reports, 13(2), 902-912. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13020079