How Do Nursing Students Perceive Moral Distress? An Interpretative Phenomenological Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Recruitment and Sampling

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Study Rigor

2.6. Ethical Consideration

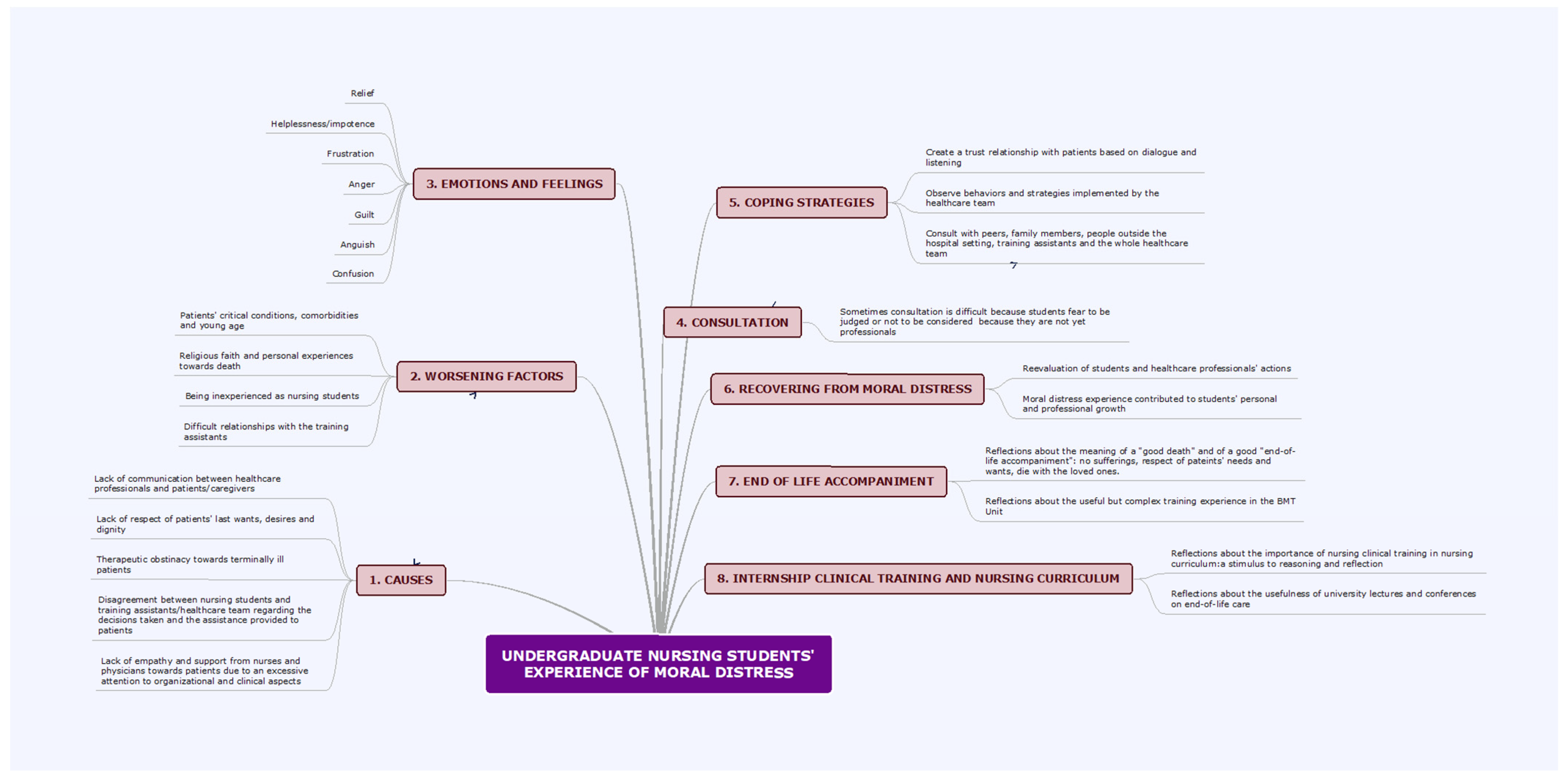

3. Results

3.1. Causes of M.D.

“[In my opinion, the decision to undergo a bone marrow transplant] seems [to have] been made by other people [rather than the patient]. It seems that it is the [patient’s] relatives who want this more than himself. Since my first day of internship clinical training, the wife has had the fixed idea of the [bone marrow transplant] into her head and [she used to say]: “Ok, you’ll undergo the bone marrow transplant”. I never saw an exchange between her and patient. The relatives [urged the patient] to get up, settle down even on days when you could see he was really tired. His wife was always trying to force him to eat, even when [it was obvious that the patient was suffering].”(13.S.18, U.S. 13.6, 13.7)

“I experienced M.D. in the onco-hematology department when I disagreed with a physician’s decision [related to a transplant] on a terminally ill patient who had other comorbidities [and therefore had an unfavorable primary condition for transplant]”.(12.S.18, U.S. 12.1)

3.2. Factors That Worsen or Influence the Experience of M.D.

“It was the first time that I was dealing with a dead patient and her relatives. I was petrified […] I was a spectator and at that very moment I didn’t act, I didn’t take charge of the situation, I didn’t say anything, I just stood there and watched… I felt emotionally unstable… I didn’t know how to behave… I didn’t know whether to go [away] or stay there and say nothing or leave [the dead patient and her husband] alone for a moment”.(06.S.18, U.S. 6.61)

3.3. Feelings and Emotions in Morally Distressing Events

“[In this situation I was feeling] so much sadness, I was feeling like crying and I was feeling dizzy. I had seen [patients] in acute situations or before or after death, but I had never lived the moment of death together with the patient”.(03.S.18, U.S. 3.94)

3.4. Morally Distressing Events and Consultation

“The fact that I talked about it with my assistant and my colleagues is a strategy [that I adopted to deal with my discomfort due to lack of communication]. Telling the story was a way to share the situation and not [bear it] alone. It was also useful to collect [different] opinions and see if that [situation] only bothered me or also others”.(05.S.18, U.S. 5.42)

3.5. Strategies to Cope with M.D.

“One strategy for dealing with the problem [was] to talk [with the patient], to distract him [by making him think about the things he liked], to make him tell me the personal episodes that I had heard from others, instead of talking about the [transplant, as he often did]”.(03.S.18, U.S. 3.51)

“Nurses are used to these situations because they live them every day and, in front of this situation, I found them quite cold. Maybe it’s a matter of habit… living [these situations related to terminally ill patients] every day creates a sort of indifference”.(10.S.18, U.S. 10.31)

3.6. Recovering from Morally Distressing Events

“I think, for better or worse, the episode with this patient has been constructive for my professional and personal growth… if I can remember it even months later, it means that it has caused a really strong reaction in me. […] I’m more and more convinced of the university choice I made, and I think that being a nurse is the right thing for me and the fact that I’ve established this relationship with her cheers me up.”(02.S.18, U.S. 2.48, 2.50)

3.7. End-of-Life Accompaniment

“I don’t think anyone can say what a patient’s end-of- life should be like specifically. But, in my opinion, when it is known that [the patient’s death] is imminent, health care professionals should try to relieve patient’s sufferings, to console him, to ask him what he wants to do to relieve [his] sufferings and to make him feel better, to help him understand what will happen so that he will have a conscious and peaceful death, [without therapeutic obstinacy].(12.18, U.S. 12.15)”

3.8. Internship Clinical Training and Nursing Curriculum

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jameton, A. Nursing practice, the ethical issues. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 1984, 22, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetta, N.; Sergi, R.; Villa, G.; Pennestrì, F.; Sala, R.; Mordacci, R.; Manara, D.F. Levels of Moral Distress among Health Care Professionals Working in Hospital and Community Settings: A Cross Sectional Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannetta, N.; Villa, G.; Pennestrì, F.; Sala, R.; Mordacci, R.; Manara, D.F. Instruments to assess moral distress among healthcare workers: A systematic review of measurement properties. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 111, 103767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, F.; Tayyar-Iravanlou, F.; Chashmi, Z.A.; Abdi, F.; Cisic, R.S. Factors affecting moral distress in nurses working in intensive care units: A systematic review. Clin. Ethics 2021, 16, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetta, N.; Villa, G.; Bonetti, L.; Dionisi, S.; Pozza, A.; Rolandi, S.; Rosa, D.; Manara, D.F. Moral Distress Scores of Nurses Working in Intensive Care Units for Adults Using Corley’s Scale: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 10640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, K.B.; Park, M. Relationship of ICU Nurses’ Difficulties in End-of-Life Care to Moral Distress, Burnout and Job Satisfaction. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2019, 25, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A.T.; White, K.R.; Epstein, E.G.; Enfield, K.B. Palliative Care and Moral Distress: An Institutional Survey of Critical Care Nurses. Crit. Care Nurse 2019, 39, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brasi, E.L.; Giannetta, N.; Ercolani, S.; Gandini, E.L.M.; Moranda, D.; Villa, G.; Manara, D.F. Nurses’ moral distress in end-of-life care: A qualitative study. Nurs. Ethics 2021, 28, 614–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corley, M.C. Moral distress of critical care nurses. Am. J. Crit. Care 1995, 4, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, E.G.; Delgado, S. Understanding and Addressing Moral Distress. Online J. Issue Nurs. 2010, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, E.G.; Hamric, A.B. Moral distress, moral residue, and the crescendo effect. J. Clin. Ethics 2009, 20, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson-Coyle, L.; Opgenorth, D.; Bellows, M.; Dhaliwal, J.; Richardson-Carr, S.; Bagshaw, S.M. Moral distress and burnout among cardiovascular surgery intensive care unit healthcare professionals: A prospective cross-sectional survey. Can. J. Crit. Care Nurs. 2016, 27, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Escolar Chua, R.L.; Magpantay, J.C.J. Moral distress of undergraduate nursing students in community health nursing. Nurs. Ethics 2019, 26, 2340–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, F.R.S.; Brehmer, L.C.d.F.; Vargas, M.A.; Trombetta, A.P.; Silveira, L.R.; Drago, L. Ethical conflicts and the process of reflection in undergraduate nursing students in Brazil. Nurs. Ethics 2015, 22, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rennó, H.M.S.; Ramos, F.R.S.; Brito, M.J.M. Moral distress of nursing undergraduates: Myth or reality? Nurs. Ethics 2018, 25, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdil, F.; Korkmaz, F. Ethical Problems Observed By Student Nurses. Nurs. Ethics 2009, 16, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokker, M.E.; Swart, S.J.; Rietjens, J.A.C.; van Zuylen, L.; Perez, R.S.G.M.; van der Heide, A. Palliative sedation and moral distress: A qualitative study of nurses. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2018, 40, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasso, L.; Bagnasco, A.; Bianchi, M.; Bressan, V.; Carnevale, F. Moral distress in undergraduate nursing students: A systematic review. Nurs. Ethics 2016, 23, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadala, M.L.A.; Silva, F.M. da Cuidando de pacientes em fase terminal: A perspectiva de alunos de enfermagem. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2009, 43, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickhoff, L.; Sinclair, P.M.; Levett-Jones, T. Moral courage in undergraduate nursing students: A literature review. Collegian 2017, 24, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, A.; Bowe, B. Phenomenology and hermeneutic phenomenology: The philosophy, the methodologies, and using hermeneutic phenomenology to investigate lecturers’ experiences of curriculum design. Qual. Quant. 2014, 48, 1291–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciani, M.; Montali, L.; Nicolò, G.; Fabrizi, D.; Di Mauro, S.; Ausili, D. Self-care is Renouncement, Routine, and Control: The Experience of Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2021, 30, 892–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cresswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Flowers, P.; Larkin, M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lillo, A. Il Mondo Della Ricerca Qualitativa, 1st ed.; UTET Università: Torino, Italy, 2010; ISBN 978-88-6008-277-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, H.; Rubin, I. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-7619-2075-5. [Google Scholar]

- Long, T.; Johnson, M. Rigour, reliability and validity in qualitative research. Clin. Eff. Nurs. 2000, 4, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M.; Barrett, M.; Mayan, M.; Olson, K.; Spiers, J. Verification Strategies for Establishing Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2002, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiers, J.; Smith, J.A.; Simpson, P.; Nicholls, A.R. The treatment experiences of people living with ileostomies: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2662–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Johnson, P.O.; Johnson, L.M.; Satele, D.V.; Shanafelt, T.D. Efficacy of the Well-Being Index to Identify Distress and Well-Being in U.S. Nurses. Nurs. Res. 2018, 67, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, D.; Bonetti, L.; Villa, G.; Allieri, S.; Baldrighi, R.; Elisei, R.F.; Ripa, P.; Giannetta, N.; Amigoni, C.; Manara, D.F. Moral Distress of Intensive Care Nurses: A Phenomenological Qualitative Study Two Years after the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, D.; Villa, G.; Togni, S.; Bonetti, L.; Destrebecq, A.; Terzoni, S. How to Protect Older Adults With Comorbidities During Phase 2 of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Nurses’ Contributions. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2020, 46, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Váchová, M. Development of a Tool for Determining Moral Distress among Teachers in Basic Schools. Pedagogika 2020, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, G.; Pennestrì, F.; Rosa, D.; Giannetta, N.; Sala, R.; Mordacci, R.; Manara, D.F. Moral Distress in Community and Hospital Settings for the Care of Elderly People. A Grounded Theory Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterkin, A.; Skorzewska, A. (Eds.) Health Humanities in Postgraduate Medical Education: A Handbook to the Heart of Medicine; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-0-19-084994-8. [Google Scholar]

- Marcomini, I.; Destrebecq, A.; Rosa, D.; Terzoni, S. Self-reported skills for ensuring patient safety and quality of care among Italian nursing students: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2022, 60, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, P.; Castoldi, M.G.; Alagna, R.A.; Brunoldi, A.; Pari, C.; Gallo, A.; Magri, M.; Marioni, L.; Muttillo, G.; Passoni, C.; et al. Validity of the Italian Code of Ethics for everyday nursing practice. Nurs. Ethics 2018, 25, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corley, M.C.; Elswick, R.K.; Gorman, M.; Clor, T. Development and evaluation of a moral distress scale. J. Adv. Nurs. 2001, 33, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvisa Palese; Anna Brugnolli Il perché di un dossier sulla ricerca qualitativa. Assist. Inferm. E Ric. 2013, 32, 172–174. [CrossRef]

| Italian Question | English Question |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Age (mean) | 22.1 | |

| Gender | Female | 15 (88.2%) |

| Male | 2 (11.8%) | |

| Internship clinical training in onco-hematological setting | Second year | 11 (64.7%) |

| Third year | 6 (35.3%) | |

| University lectures about nursing in the end-of life care in the second year of nursing school | Yes, before the internship clinical training | 7 (63.6%) |

| Yes, after the internship clinical training | 4 (36.34%) | |

| University lectures about ethics and moral philosophy in the third year of nursing school | Yes, before the internship clinical training | 3 (50%) |

| Yes, after the internship clinical training | 3 (50%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gandossi, C.; De Brasi, E.L.; Rosa, D.; Maffioli, S.; Zappa, S.; Villa, G.; Manara, D.F. How Do Nursing Students Perceive Moral Distress? An Interpretative Phenomenological Study. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 539-548. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13010049

Gandossi C, De Brasi EL, Rosa D, Maffioli S, Zappa S, Villa G, Manara DF. How Do Nursing Students Perceive Moral Distress? An Interpretative Phenomenological Study. Nursing Reports. 2023; 13(1):539-548. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13010049

Chicago/Turabian StyleGandossi, Chiara, Elvira Luana De Brasi, Debora Rosa, Sara Maffioli, Sara Zappa, Giulia Villa, and Duilio Fiorenzo Manara. 2023. "How Do Nursing Students Perceive Moral Distress? An Interpretative Phenomenological Study" Nursing Reports 13, no. 1: 539-548. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13010049

APA StyleGandossi, C., De Brasi, E. L., Rosa, D., Maffioli, S., Zappa, S., Villa, G., & Manara, D. F. (2023). How Do Nursing Students Perceive Moral Distress? An Interpretative Phenomenological Study. Nursing Reports, 13(1), 539-548. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13010049