Workplace Stress in Portuguese Oncology Nurses Delivering Palliative Care: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.2. Research Problem

2. Materials and Methods

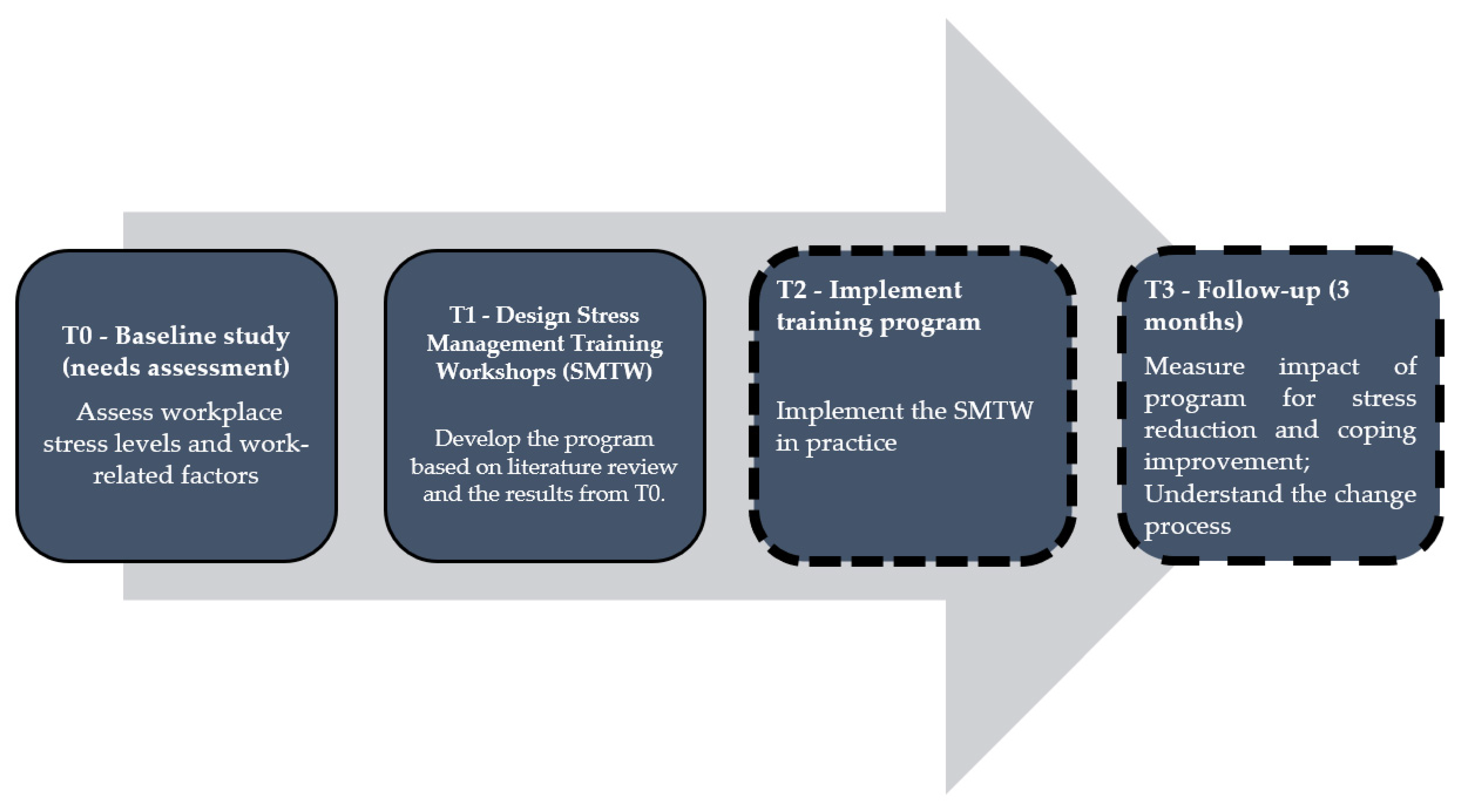

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Procedures

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Nurse Workplace Stress

3.2.1. The Intrapersonal Domain of Nurse Workplace Stress

3.2.2. The Interpersonal Domain of Nurse Workplace Stress

3.2.3. The Organizational Domain of Nurse Workplace Stress

4. Discussion

4.1. Contributions to the Development of Stress Management Training Workshops (SMTW)

4.2. Study Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nowrouzi, B.; Lightfoot, N.; Larivière, M.; Carter, L.; Rukholm, E.; Schinke, R.; Belanger-Gardner, D. Occupational Stress Management and Burnout Interventions in Nursing and Their Implications for Healthy Work Environments. Workplace Health Saf. 2015, 63, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakusic, J.; Lenderink, A.; Lambreghts, C.; Vandenbroeck, S.; Verbeek, J.; Curti, S.; Mattioli, S.; Godderis, L. Methodologies to Identify Work-Related Diseases—Review of Sentinel and Alert Approaches; European Risk Observatory Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Ora, C.; Ball, J.; Reinius, M.; Griffiths, P. Burnout in nursing: A theoretical review. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuhara, M.; Sato, K.; Kodama, Y. The nurses’ occupational stress components and outcomes, findings from an integrative review. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 2153–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukan, J.; Bolliger, L.; Pauwels, N.S.; Luštrek, M.; Bacquer, D.; Clays, E. Work environment risk factors causing day-to-day stress in occupational settings: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdoh, D.S.; Shahin, M.A.; Ali, A.K.; Alhejaili, S.M.; Kiram, O.M.; Al-Dubai, S.A.R. Prevalence and associated factors of stress among primary health care nurses in Saudi Arabia, a multi-center study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 2692–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; Abdul Ghani, A.B.; Subhan, M.; Joarder, M.; Ridzuan, A. The Relationship between Stress and Job Satisfaction: An Evidence from Malaysian Peacekeeping Mission. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fasbender, U.; Heijden, B.I.; Grimshaw, S. Job satisfaction, job stress and nurses’ turnover intentions: The moderating roles of on-the-job and off-the-job embeddedness. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandi, G.; Shahzad, I.; Farrukh, M.; Kot, S. Supporting Role of Society and Firms to COVID-19 Management among Medical Practitioners. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; van der Heijden, B.; Guo, Z. The Role of Filial Piety in the Relationships between Work Stress, Job Satisfaction, and Turnover Intention: A Moderated Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foli, K.J.; Reddick, B.; Zhang, L.; Krcelich, K. Substance Use in Registered Nurses: “I Heard About a Nurse Who …”. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2020, 26, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S.D.; Kaushik, A.; Ravikiran, S.; Suprasanna, K.; Nayak, M.G.; Baliga, K. Depression, anxiety, stress and workplace stressors among nurses in tertiary health care settings. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 25, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin, L.I.; Fukowska, M.; Zyskowska, D.; Olechowska, J.; Czarkowska-Pączek, B. Impact of stress and coping strategies on insomnia among Polish novice nurses who are employed in their field while continuing their education: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e049787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havaei, F.; Ji, X.R.; MacPhee, M.; Straight, H. Identifying the most important workplace factors in predicting nurse mental health using machine learning techniques. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, B.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wu, L.; Cao, F. Suicidal ideation among nurses: Unique and cumulative effects of different subtypes of sleep problems. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 276, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandinetti, P.; Gooney, M.; Scheibein, F.; Testa, R.; Ruggieri, G.; Tondo, P.; Corona, A.; Boi, G.; Floris, L.; Profeta, V.F.; et al. Stress and Maladaptive Coping of Italians Health Care Professionals during the First Wave of the Pandemic. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roster, C.A.; Ferrari, J.R. Does Work Stress Lead to Office Clutter, and How? Mediating Influences of Emotional Exhaustion and Indecision. Environ. Behav. 2019, 52, 923–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunita, P.I.; Saputra, I.G.N.W.H. Millennial generation in accepting mutations: Impact on work stress and employee performance. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2019, 3, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Martínez-Zaragoza, F.; Benavides-Gil, G.; Rovira, T.; Martín-Del-Río, B.; Edo, S.; García-Sierra, R.; Solanes-Puchol, Á.; Fernández-Castro, J. When and how do hospital nurses cope with daily stressors? A multilevel study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betke, K.; Basińska, M.A.; Andruszkiewicz, A. Sense of coherence and strategies for coping with stress among nurses. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velana, M.; Rinkenauer, G. Individual-Level Interventions for Decreasing Job-Related Stress and Enhancing Coping Strategies Among Nurses: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 708696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Jang, I. Nurses’ Fatigue, Job Stress, Organizational Culture, and Turnover Intention: A Culture-Work-Health Model. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2019, 42, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junker, S.; Pömmer, M.; Traut-Mattausch, E. The impact of cognitive-behavioural stress management coaching on changes in cognitive appraisal and the stress response: A field experiment. Coach. Int. J. Theory Res. Pract. 2021, 14, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Anjum, Z.-U.-Z.; Naeem, B.; Qammar, A.; Anwar, F. Personal Demands and Personal Resources as Facilitators to Reduce Burnout: A Lens of Self Determination Theory. In Paradigms; University of Central Punjab: Lahore, Pakistan, 2019; Volume 13, Available online: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A603360452/AONE?u=anon~6bb22d5c&sid=googleScholar&xid=29e2c349 (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Jetha, A.; Kernan, L.; Kurowski, A. Pro-Care Research Team Conceptualizing the dynamics of workplace stress: A systems-based study of nursing aides. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, F.; Malik, M.I.; Qureshi, S.S. Work Stress Hampering Employee Performance During COVID-19: Is Safety Culture Needed? Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 655839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, R.; Robinson, J.; Wong, C.; Gott, M. Burnout, compassion fatigue and psychological capital: Findings from a survey of nurses delivering palliative care. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2018, 43, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llapa-Rodriguez, E.O.; De Oliveira, J.K.A.; Neto, D.L.; Gois, C.F.L.; Campos, M.P.D.A.; De Mattos, M.C.T. Estresse ocupacional em profissionais de enfermagem. Rev. Enferm. UERJ 2018, 26, e19404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, N.; Costeira, C.; Silva, A.; Moreira, I. Efetividade de um programa de formação na gestão emocional dos enfermeiros perante a morte do doente. Rev. Enferm. Ref. 2020, 5, e20023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, K. Palliative Cancer Care Stress and Coping Among Clinical Nurses Who Experience End-of-Life Care. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2020, 22, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beng, T.S.; Ting, T.T.; Karupiah, M.; Ni, C.X.; Li, H.L.; Guan, N.C.; Chin, L.E.; Loong, L.C.; Pin, T.M. Patterns of Suffering in Palliative Care: A Descriptive Study. Omega J. Death Dying 2020, 84, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.K.; Sawyer, A.T.; Robinson, P.S. A Psychoeducational Group Intervention for Nurses: Rationale, Theoretical Framework, and Development. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Teixeira, Z. O stresse profissional dos enfermeiros. In Revista da Faculdade de Ciências Da Saúde; Universidade Fernando Pessoa: Porto, Portuguese, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, R.; Lee, S.F.; Bloomer, M. How nurses cope with patient death: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 27, e39–e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, K.T.C.; Chow, A.Y.M.; Chan, I.K.N. Effectiveness of Educational Programs on Palliative and End-of-life Care in Promoting Perceived Competence Among Health and Social Care Professionals. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2021, 39, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henshall, C.; Davey, Z.; Jackson, D. Nursing resilience interventions—A way forward in challenging healthcare territories. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 3597–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerlin, M.P.; McPeake, J.; Mikkelsen, M. Burnout and Joy in the Profession of Critical Care Medicine. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miligi, E.; Alshutwi, S.; Alqahtani, M. The Impact of Work Stress on Turnover Intentions among Palliative Care Nurses in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Nurs. 2019, 6, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.C.; Manna, R.; Coyle, N.; Penn, S.; Gallegos, T.E.; Zaider, T.; Krueger, C.A.; Bialer, P.A.; Bylund, C.L.; Parker, P.A. The implementation and evaluation of a communication skills training program for oncology nurses. Transl. Behav. Med. 2017, 7, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Başoğul, C.; Özgür, G. Role of Emotional Intelligence in Conflict Management Strategies of Nurses. Asian Nurs. Res. 2016, 10, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhshani, T.; Motlagh, Z.; Beigi, V.; Rahimkhanli, M.; Rashki, M. The Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Job Stress among Nurses in Shiraz, Iran. Malays. J. Med Sci. 2018, 25, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, A.; Meshkinyazd, A.; Soudmand, P. The Effect of Spiritual Intelligence Training on Job Satisfaction of Psychiatric Nurses. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2017, 12, 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Cocchiara, R.A.; Peruzzo, M.; Mannocci, A.; Ottolenghi, L.; Villari, P.; Polimeni, A.; Guerra, F.; La Torre, G. The Use of Yoga to Manage Stress and Burnout in Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; He, G.; Yan, J.; Gu, C.; Xie, J. The Effects of a Modified Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Program for Nurses: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Workplace Health Saf. 2018, 67, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozgundondu, B.; Metin, Z.G. Effects of progressive muscle relaxation combined with music on stress, fatigue, and coping styles among intensive care nurses. Intensiv. Crit. Care Nurs. 2019, 54, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaca, A.; Şişman, N.Y. Effects of a Stress Management Training Program With Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction. J. Nurs. Educ. 2019, 58, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Riet, P.; Levett-Jones, T.; Aquino-Russell, C. The effectiveness of mindfulness meditation for nurses and nursing students: An integrated literature review. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 65, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, M.; Melnyk, B.M.; Hoying, J. Intervention Effects of the MINDBODYSTRONG Cognitive Behavioral Skills Building Program on Newly Licensed Registered Nurses’ Mental Health, Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors, and Job Satisfaction. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2019, 49, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods-Giscombe, C.L. An innovative program to promote health promotion, quality of life, and wellness for School of Nursing faculty, staff, and students: Facilitators, barriers, and opportunities for broad system-level and cultural change. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2020, 35, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyess, S.M.; Sherman, R.; Opalinski, A.; Eggenberger, T. Structured Coaching Programs to Develop Staff. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2017, 48, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ebner, K.; Schulte, E.-M.; Soucek, R.; Kauffeld, S. Coaching as stress-management intervention: The mediating role of self-efficacy in a framework of self-management and coping. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2018, 25, 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suikkala, A.; Tohmola, A.; Rahko, E.K.; Hökkä, M. Future palliative competence needs—A qualitative study of physicians’ and registered nurses’ views. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, B. Research into experiential learning in nurse education. Br. J. Nurs. 2017, 26, 932–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callus, E.; Bassola, B.; Fiolo, V.; Bertoldo, E.G.; Pagliuca, S.; Lusignani, M. Stress Reduction Techniques for Health Care Providers Dealing With Severe Coronavirus Infections (SARS, MERS, and COVID-19): A Rapid Review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 589698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manansingh, S.; Tatum, S.L.; Morote, E.-S. Effects of Relaxation Techniques on Nursing Students’ Academic Stress and Test Anxiety. J. Nurs. Educ. 2019, 58, 534–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abiogu, G.C.; Ede, M.O.; Agah, J.J.; Ugwuozor, F.O.; Nweke, M.; Nwosu, N.; Nnamani, O.; Eskay, M.; Obande-Ogbuinya, N.E.; Ogheneakoke, C.E.; et al. Cognitive-behavioural reflective training for improving critical thinking disposition of nursing students. Medicine 2020, 99, e22429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartzik, M.; Bentrup, A.; Hill, S.; Bley, M.; von Hirschhausen, E.; Krause, G.; Ahaus, P.; Dahl-Dichmann, A.; Peifer, C. Care for Joy: Evaluation of a Humor Intervention and Its Effects on Stress, Flow Experience, Work Enjoyment, and Meaningfulness of Work. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 667821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laranjeira, C.A.; Querido, A.I. Assertiveness Training of Novice Psychiatric Nurses: A Necessary Approach. Issues Ment. Heal. Nurs. 2020, 42, 699–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahrbaaki, P.M.; Farokhzadian, J.; Miri, S.; Doostkami, M.; Rezahosseini, Z. Promoting the psychosocial and communication aspects of nursing care quality using time management skills training. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 9, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chahrour, W.H.; Hvidt, N.C.; Hvidt, E.A.; Viftrup, D.T. Learning to care for the spirit of dying patients: The impact of spiritual care training in a hospice-setting. BMC Palliat. Care 2021, 20, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.; Wand, T.; Fraser, J.A. Exploring the meaning and practice of self-care among palliative care nurses and doctors: A qualitative study. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | Md | Percentile 25 | Percentile 75 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor I—Death and dying | 2.89 | 0.66 | 2.71 | 2.29 | 3.75 |

| Factor II—Conflicts with doctors | 2.54 | 0.75 | 2.40 | 2.00 | 3.00 |

| Factor III—Inadequate preparation to deal with the emotional needs of patients and their families | 2.74 | 0.81 | 2.67 | 2.00 | 3.58 |

| Factor IV—Lack of support from colleagues | 2.63 | 0.82 | 2.50 | 2.00 | 3.33 |

| Factor V—Conflicts with other peers and nurse managers | 2.55 | 0.73 | 2.40 | 2.40 | 3.20 |

| Factor VI—Workload | 2.87 | 0.68 | 2.83 | 2.33 | 3.58 |

| Factor VIII—Uncertainty with treatments | 2.88 | 0.79 | 2.60 | 2.20 | 3.90 |

| Global score | 2.66 | 0.62 | 2.41 | 2.26 | 3.35 |

| Age | Current Service Experience | Years of Profession | Training in Palliative Care | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs | rs | rs | U | p | With Training | No Training | ||

| Md | Md | |||||||

| Factor I: Death and dying | −0.52 ** | −0.51 ** | −0.50 ** | 27.00 | 0.04 | 3.57 | 2.71 | |

| items | 3. Perform procedures that patients feel as painful | −0.48 ** | −0.46 ** | −0.48 ** | 19.00 | 0.01 | 4.00 | 3.00 |

| 4. Feeling powerless when a patient does not improve with treatments | −0.62 ** | −0.62 ** | −0.61 ** | 24.00 | 0.02 | 4.00 | 3.00 | |

| 6. Talking to the patient about the proximity of death | −0.41 * | −0.43 * | −0.42 * | 33.00 | 0.06 | 3.00 | 2.00 | |

| 8. The death of a patient | −0.15 | −0.15 | −0.12 | 50.50 | 0.34 | 3.00 | 2.00 | |

| 12. The death of a patient with whom a close relationship has developed | −0.42 * | −0.40 * | −0.39 * | 39.50 | 0.13 | 3.00 | 2.00 | |

| 13. Absence of the doctor when a patient dies | −0.29 | −0.29 | −0.28 | 48.50 | 0.31 | 4.00 | 3.00 | |

| 21. Seeing a sick person in pain | −0.47 ** | −0.47 ** | −0.45 * | 39.00 | 0.10 | 4.00 | 3.00 | |

| Factor III: Inadequate preparation to deal with the emotional needs of patients and their families | −0.33 | −0.33 | −0.31 | 16.00 | 0.01 | 3.67 | 2.33 | |

| items | 15. Lack of preparation to support the patient’s family in their emotional needs | −0.25 | −0.23 | −0.24 | 32.50 | 0.06 | 4.00 | 3.00 |

| 18. Not having an adequate answer to a question posed by the patient | −0.28 | −0.29 | −0.271 | 18.00 | 0.01 | 4.00 | 2.00 | |

| 23. Feeling unprepared to support the patient’s emotional needs | −0.31 | −0.31 | −0.29 | 19.00 | 0.01 | 4.00 | 2.00 | |

| Factor VII: Uncertainty about treatments | −0.43 * | −0.44 * | −0.43 * | 27.00 | 0.03 | 4.00 | 2.60 | |

| items | 17. Inadequate information provided by the physician regarding the patient’s clinical situation | −0.47 ** | −0.474 ** | −0.46 ** | 34.50 | 0.07 | 4.00 | 3.00 |

| 26. Medical prescriptions apparently inappropriate for the treatment of a patient | −0.34 | −0.364 * | −0.34 | 19.00 | 0.01 | 4.00 | 2.00 | |

| 31. Absence of a doctor during a medical emergency | −0.47 ** | −0.472 ** | −0.47 ** | 29.00 | 0.03 | 4.00 | 2.00 | |

| 32. Not knowing what to say to the patient and family about their condition and treatment | −0.31 | −0.304 | −0.29 | 40.50 | 0.14 | 4.00 | 3.00 | |

| 33. Doubts regarding the operation of certain specialized equipment | −0.45 * | −0.444 * | −0.44 * | 35.00 | 0.06 | 4.00 | 2.00 | |

| Age | Current Service Experience | Years of Profession | Training in Palliative Care | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs | rs | rs | U | p | With Training | No Training | ||

| Md | Md | |||||||

| Factor II: Conflicts with doctors | −0.33 | −0.37 * | −0.33 | 10.00 | 0.00 | 3.80 | 2.20 | |

| items | 2. Being criticized by a doctor | −0.36 * | −0.41 * | −0.37 * | 7.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 |

| 9. Conflict with a doctor | −0.36 * | −0.39 * | −0.35 * | 9.000 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | |

| 10. Fear of making mistakes when treating a patient | −0.21 | −0.27 | −0.22 | 25.50 | 0.02 | 4.00 | 2.00 | |

| 14. Disagreement regarding the treatment of a patient | −0.26 | −0.29 | −0.27 | 26.00 | 0.02 | 4.00 | 2.00 | |

| 19. Making a decision regarding the patient’s treatment | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 36.00 | 0.07 | 3.00 | 2.00 | |

| Factor IV: Lack of peer support | −0.33 | −0.33 | −0.31 | 16.00 | 0.01 | 3.33 | 2.33 | |

| Items | 7. Lack of opportunity to speak openly with other team members about service | −0.14 | −0.18 | −0.15 | 42.50 | 0.18 | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| 11. Lack of opportunity to share experiences and feelings with other team members | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.01 | 62.50 | 0.79 | 3.00 | 2.00 | |

| 16. Lack of opportunity to express negative feelings about the patient to other team members | −0.36 * | −0.35 * | −0.33 | 36.00 | 0.08 | 4.00 | 2.00 | |

| Factor V: Conflicts with other nurses and bosses | −0.21 | −0.21 | −0.18 | 46.50 | 0.27 | 3.40 | 2.20 | |

| items | 5. Conflict with a superior | −0.55 ** | −0.55 ** | −0.53 ** | 24.50 | 0.02 | 4.00 | 2.00 |

| 20. Being mobilized to another service to make up for staff shortages | −0.59 ** | −0.58 ** | −0.58 ** | 25.00 | 0.02 | 4.00 | 2.00 | |

| 22. Difficulty working with a particular nurse (or nurses) from another service | −0.04 | −0.08 | −0.05 | 53.00 | 0.41 | 2.00 | 2.00 | |

| 24. Receiving criticism from a superior | −0.39 * | −0.42 * | −0.39 * | 7.500 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | |

| 29. Difficulty working with a particular nurse (or nurses) from the same service | −0.17 | −0.23 | −0.19 | 56.00 | 0.52 | 3.00 | 2.00 | |

| Age | Current Service Experience | Years of Profession | Training in Palliative Care | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs | rs | rs | U | rs | With Training | No Training | ||

| Md | Md | |||||||

| Factor VI: Workload | −0.35 * | −0.38 * | −0.36 * | 24.00 | 0.02 | 4.00 | 2.00 | |

| Items | 1. Computer malfunction | −0.23 | −0.24 | −0.24 | 42.00 | 0.13 | 4.00 | 2.00 |

| 25. Unexpected changes to the schedule and work plan | −0.45 * | −0.47 ** | −0.45 * | 34.50 | 0.07 | 4.00 | 3.00 | |

| 27. Too many tasks outside the strict professional scope, such as administrative work | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.00 | 52.00 | 0.39 | 4.00 | 3.00 | |

| 28. Lack of time to give emotional support to the patient | −0.29 | −0.32 | −0.29 | 28.00 | 0.03 | 4.00 | 3.00 | |

| 30. Lack of time to perform all nursing activities | −0.37 * | −0.39 * | −0.37 * | 38.00 | 0.10 | 4.00 | 3.00 | |

| 34. Lack of personnel to adequately cover the service needs | −0.45 ** | −0.46 ** | −0.45 ** | 33.00 | 0.05 | 4.00 | 2.00 | |

| Session | Assignments | Change Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| Workshop 1 | Psychoeducation session (definition, causes, and consequences of social and occupational life, as well as stress management styles and strategies); a psychoeducation pamphlet should be produced. | This educational approach increases knowledge and learning about the underlying causes of mental health problems and which evidence-based interventions can be used to treat such issues [32]. The pamphlet provides advice on finding indicators of stress and on relaxation and sleep hygiene, as well as stress reduction strategies such as exercise, laughter, and connecting with close friends. |

| Workshop 2 | Relaxation techniques training (1—Deep Breathing Exercise; 2—Progressive Relaxation Techniques; and 3—Body scan, mindfulness meditation, self-compassion techniques). | By encouraging non-judgmental self-awareness and self-care, the participant gains a more stable and positive sense of self. The individual uses abilities to defend oneself, manage resources, and comfort oneself and others [54,55]. Emotion identification, self-validation, acknowledging and reframing self-critical thoughts, mindfulness meditation, and affirmations are all examples of self-compassion abilities [32]. |

| Workshop 3 | Positive self-talk and problem-solving skills are part of the cognitive restructuring techniques developed in this session. | This assignment focuses on recognizing misunderstandings, influencing skewed thinking, and thus reducing anxiety and boosting problem-solving abilities and reasoned practice [56]. |

| Workshop 4 | Humor therapy, in which participants practice humor through several methods (laughing videos, laughter meditation, sharing personal tales and jokes, and exchanging joyful ideas). | The participant improves emotion management by visual and linguistic expression of emotions, externalizing these feelings. In the nursing context, humor increases communication, well-being, and positive affect [57]. Individuals convey how they feel by expressing emotions and handling things in a constructive/helpful, comforting, and calming manner. |

| Workshop 5 | Assertiveness training and time management. | The participant gains communication skills in the development and maintenance of strong interpersonal connections at work, as well as successful team functioning [58]. Individuals should leave this workshop with the necessary skills and information to speak more confidently and successfully, by employing assertive behavior tactics.This assignment also focuses on time management skills such as preparing lists, scheduling tasks, checking off each activity as it is completed, and avoiding distractions [59]. |

| Workshop 6 | Self-care training in facing death and dying—spirituality care. | Self-care reflexive individual exercises or in small groups, with different instruments (e.g., reflexive writing, visual aids, or storytelling).Topics discuss and reflect on personal values, including spirituality, being present during pain, the concept of dignity, spiritual self-care, hope, death, and the afterlife [60]. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Costeira, C.; Ventura, F.; Pais, N.; Santos-Costa, P.; Dixe, M.A.; Querido, A.; Laranjeira, C. Workplace Stress in Portuguese Oncology Nurses Delivering Palliative Care: A Pilot Study. Nurs. Rep. 2022, 12, 597-609. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep12030059

Costeira C, Ventura F, Pais N, Santos-Costa P, Dixe MA, Querido A, Laranjeira C. Workplace Stress in Portuguese Oncology Nurses Delivering Palliative Care: A Pilot Study. Nursing Reports. 2022; 12(3):597-609. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep12030059

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosteira, Cristina, Filipa Ventura, Nelson Pais, Paulo Santos-Costa, Maria Anjos Dixe, Ana Querido, and Carlos Laranjeira. 2022. "Workplace Stress in Portuguese Oncology Nurses Delivering Palliative Care: A Pilot Study" Nursing Reports 12, no. 3: 597-609. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep12030059

APA StyleCosteira, C., Ventura, F., Pais, N., Santos-Costa, P., Dixe, M. A., Querido, A., & Laranjeira, C. (2022). Workplace Stress in Portuguese Oncology Nurses Delivering Palliative Care: A Pilot Study. Nursing Reports, 12(3), 597-609. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep12030059