Midwifery Qualification in Selected Countries: A Rapid Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

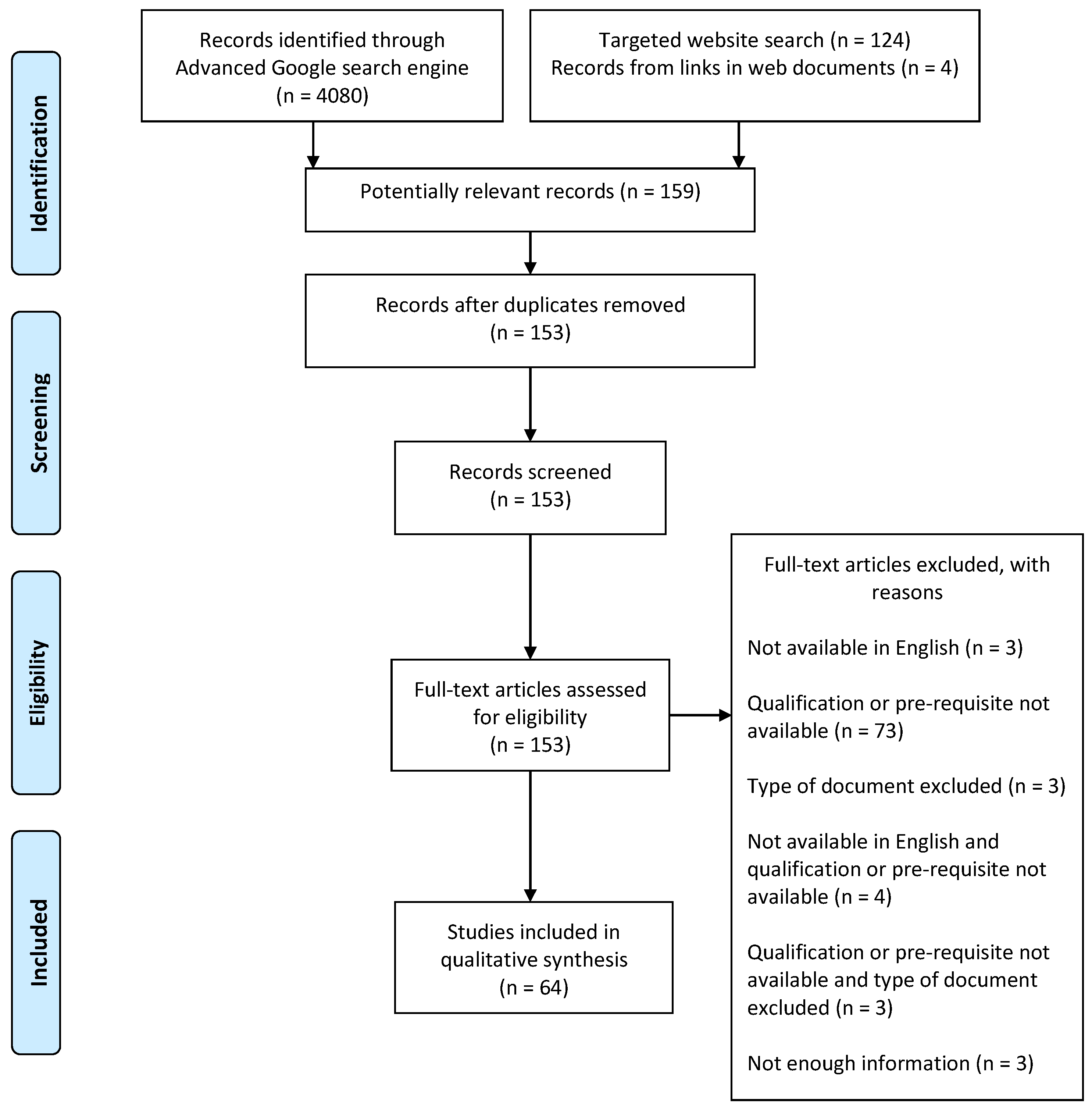

2. Materials and Methods

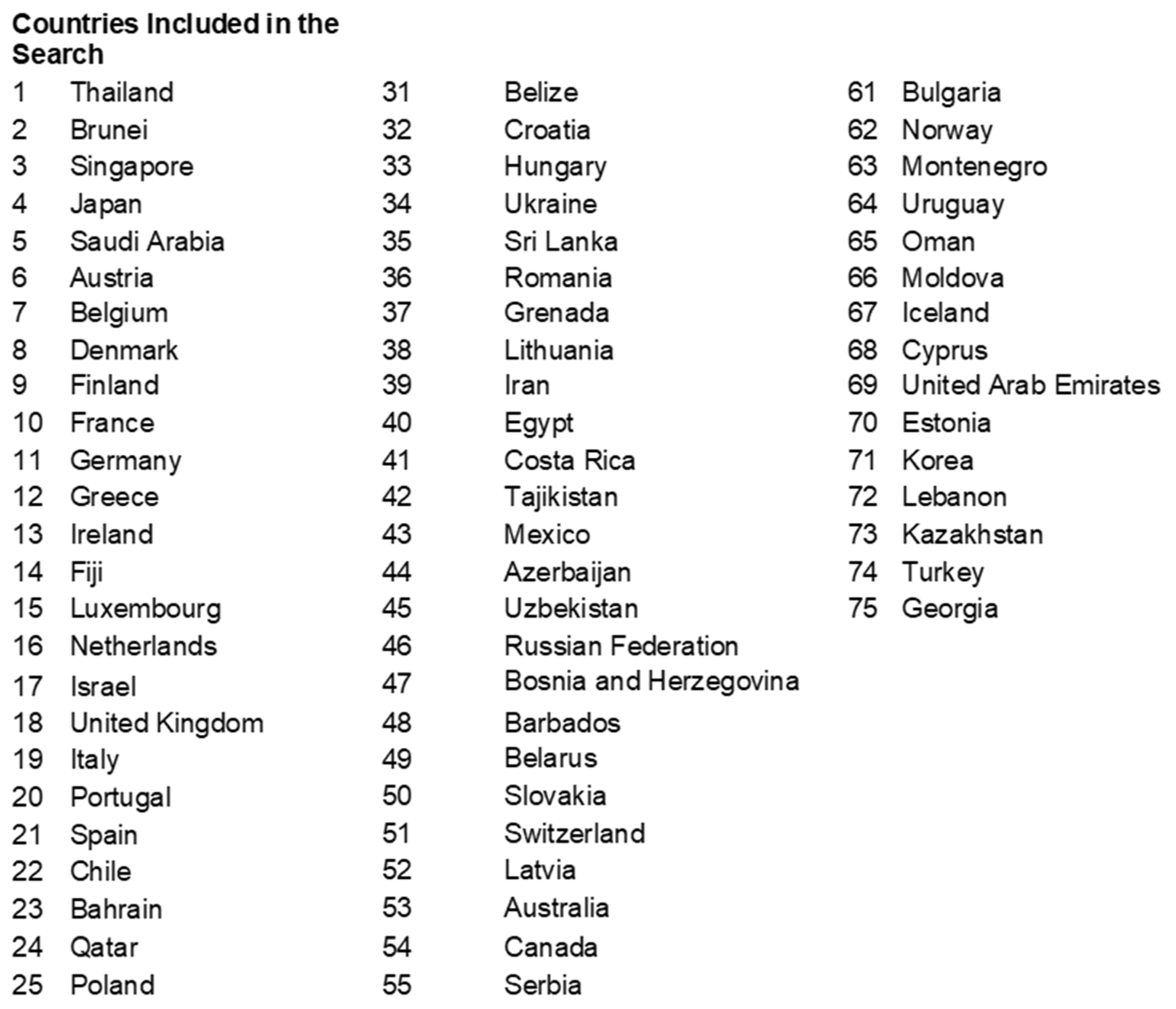

2.1. Study Search

2.2. Study Inclusion

2.3. Study Selection, Quality Assessment and Data Extraction

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Included Documents

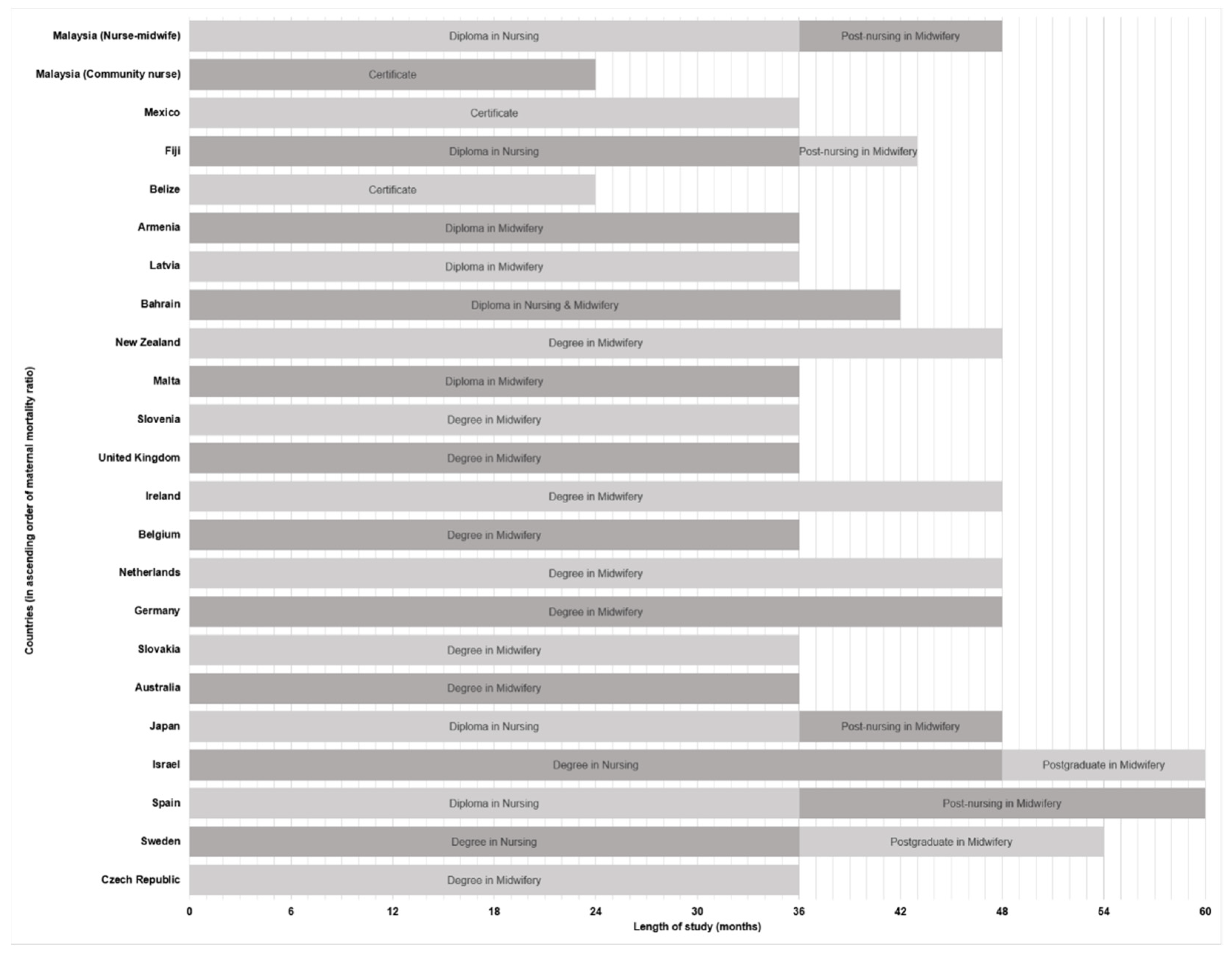

3.2. The Minimum Midwifery Qualification

3.3. Other Requirements to Practise as a Recognised Midwife

4. Discussion

4.1. Higher-Educated Midwives Add Value to the Practice

4.2. Producing Work-Ready, Quality-Assured Midwives

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Roser, M.; Ritchie, H. Maternal Mortality. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/maternal-mortality (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- World Health Organization. Maternal Mortality [Fact Sheet]. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- World Bank. Maternal Mortality Ratio (Modeled Estimate, per 100,000 Live Births). 2015. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/sh.sta.mmrt (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- Say, L.; Chou, D.; Gemmill, A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Moller, A.B.; Daniels, J.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Temmerman, M.; Alkema, L. Global causes of maternal death: A WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2014, 2, e323–e333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dumont, A.; Fournier, P.; Abrahamowicz, M.; Traoré, M.; Haddad, S.; Fraser, W.D. Quality of care, risk management, and technology in obstetrics to reduce hospital-based maternal mortality in Senegal and Mali (QUARITE): A cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2013, 382, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.C.; Kitsantas, P. A review of maternal mortality and quality of care in the USA. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 33, 3355–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, S.E.; Koch, A.R.; Garland, C.E.; MacDonald, E.J.; Storey, F.; Lawton, B. A global view of severe maternal morbidity: Moving beyond maternal mortality. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Maternal Health: Overview. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/maternal-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Jennings, M.C.; Pradhan, S.; Schleiff, M.; Sacks, E.; Freeman, P.A.; Gupta, S.; Rassekh, B.M.; Perry, H.B. Comprehensive review of the evidence regarding the effectiveness of community-based primary health care in improving maternal, neonatal and child health: 2. maternal health findings. J. Glob. Health 2017, 7, 010902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumakech, E.; Anathan, J.; Udho, S.; Auma, A.G.; Atuhaire, I.; Nsubuga, A.G.; Ahaisibwe, B. Graduate Midwifery Education in Uganda Aiming to Improve Maternal and Newborn Health Outcomes. Ann. Glob. Health 2020, 86, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Strategies toward Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality (EPMM); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- International Confederation of Midwives. Global Standards for Midwifery Education; International Confederation of Midwives: The Hague, Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Malaysia Health System Review; WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific: Manila, Philippines, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Public Health. National Health and Morbidity Survey 2016: Maternal and Child Health (MCH), Volume Two: Maternal and Child Health Findings; Institute for Public Health: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Country Report: Malaysia. 2006. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kokusaigyomu/asean/asean/kokusai/siryou/dl/h18_malaysia1.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- Ministry of Health Malaysia. Health Facts 2019, Reference Data for 2018; Ministry of Health Malaysia: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sindot, S. (Community Nurses in Malaysia). Personal communication, 2019.

- Pathmanathan, I.; Liljestrand, J.; Martins, J.M.; Rajapaksa, L.C.; Lissner, C.; de Silva, A.; Selvaraju, S.; Singh, P.J. Investing in Maternal Health: Learning from Malaysia and Sri Lanka. Health, Nutrition, and Population; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Malaysia. Perinatal Care Manual, 3rd ed.; Ministry of Health Malaysia: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, J.; Singh, H. Maternal Health in Malaysia: A Review. WebmedCentral Public Health 2011, 2, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfrew, M.J.; McFadden, A.; Bastos, M.H.; Campbell, J.; Channon, A.A.; Cheung, N.F.; Silva, D.R.A.D.; Downe, S.; Kennedy, H.P.; Malata, A. Midwifery and quality care: Findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. Lancet 2014, 384, 1129–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Langlois, E.V.; Straus, S.E. Rapid Reviews to Strengthen Health Policy and Systems: A Practical Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shakirah, M.S.; Fun, W.H.; Kong, Y.L.; Anis-Syakira, J.; Balqis-Ali, N.Z.; Sindot, S.; Sararaks, S.; Shauki, N.I.A.A. Midwifery Qualification in Primary Care. 2019. Available online: https://osf.io/gzn3a/ (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Alajaijian, S.; Ho, T. Optimizing the Identification of Grey Literature: A Rapid Review. Available online: https://www.peelregion.ca/health/library/pdf/rapid-reviews/optimizing-indentification-grey-literature.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2019).

- Tyndall, J. AACODS Checklist. Available online: http://dspace.flinders.edu.au/jspui/handle/2328/3326 (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia. Registration Standards. Available online: https://www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/registration-standards.aspx (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Australian Nursing and Midwifery Accreditation Council. Midwife Accreditation Standards 2014; Australian Nursing and Midwifery Accreditation Council: Canberra, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nursing Midwifery Board of Ireland. Registration. Available online: https://www.nmbi.ie/Registration (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Nursing Midwifery Board of Ireland. Careers in Nursing and Midwifery: Where to Study to Become a Nurse or Midwife? Available online: https://www.nmbi.ie/Careers-in-Nursing-Midwifery/Becoming-a-Nurse-Midwife/Where-to-study (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Nursing and Midwifery Council. Becoming a Midwife. Available online: https://www.nmc.org.uk/education/becoming-a-nurse-midwife-nursing-associate/becoming-a-midwife/ (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Singapore Nursing Board. Local Graduates. Available online: http://www.healthprofessionals.gov.sg/snb/registration-enrolment/application-for-registration-enrolment/local-graduates (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Midwifery Council of New Zealand. What Does It Take to Qualify as a Midwife? Available online: https://www.midwiferycouncil.health.nz/professional-standards/what-does-it-take-qualify-midwife (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Midwifery Council of New Zealand. Maintaining Competence. Available online: https://www.midwiferycouncil.health.nz/midwives/maintaining-competence (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Midwifery Council of New Zealand. Becoming Registered to Practise. Available online: https://www.midwiferycouncil.health.nz/midwives/becoming-registered-practise (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Midwifery Education and Accreditation Council. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). Available online: http://meacschools.org/education-faq/ (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- North American Registry of Midwives. How to Become a CPM. Available online: http://narm.org/certification/how-to-become-a-cpm/ (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Regulation on the Education, Rights and Obligations of Midwives and Criteria for Granting of Licences and Specialist Licences No. 1089/2012; Ministry of Welfare: Rekjavic, Iceland, 2012.

- Act on Public Health Nurses, Midwives, and Nurses, Act No. 203 1948. Japan. Available online: http://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/law/detail_main?id=2075&re=02&vm=02 (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- Midwifery Act (Consolidated Text, OG 120/08, 145/10); The Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2008.

- Health Care Professions Act, Chapter 464; Ministry of Justice and Home Affairs: Valletta, Malta, 2003.

- Nurses and Midwives Act Chapter 209, 2012 Revised Edition; The Law Revision Commission: Singapore, 2012.

- Lebanese Order of Midwives. 2018. Available online: https://www.daleel-madani.org/civil-society-directory/lebanese-order-midwives (accessed on 16 March 2019).

- Law on Regulated Professions and Recognition of Professional Qualifications; Latvijas Vēstnesis: Riga, Latvia, 2001.

- Nursing and Midwifery Profession Act B.E. 2528; Royal Thai Government Gazette: Bangkok, Thailand, 1985.

- Chapter 194 Midwives Act; Renada. 2003. Available online: http://grenada.mylexisnexis.co.za/# (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- Nurses and Midwives Registration Act, Chapter 321, Revised Edition 2003; Law Revision Comissioner: Belmopan, Belize, 2003.

- Medical Ordinance, Chapter 113; Blackhall Publishing: Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka, 2018.

- Emons, J.K.; Luiten, M.I.J. Midwifery in Europe: An Inventory in fifteen EU-Member States; Deloitte & Touche: Leusden, The Netherland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Berdún, D. The competences of midwives in Spain over time. In Maternity Care in Different Countries. Midwife’s Contribution, 1st ed.; Escuriet, R., Ed.; Consell de Collegis d’Infermeres i Infermers de Catalunya Rosselló: Barcelona, Spain, 2016; pp. 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Leon-Larios, F. The current situation of midwives in Spain. In Maternity Care in Different Countries. Midwife’s Contribution, 1st ed.; Escuriet, R., Ed.; Consell de Collegis d’Infermeres i Infermers de Catalunya Rosselló: Barcelona, Spain, 2016; pp. 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Japanese Nursing Association. Midwifery in Japan; Japanese Nursing Association: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Beeckman, K.; Reyns, M. Midwifery in Belgium. In Maternity Care in Different Countries. Midwife’s Contribution, 1st ed.; Escuriet, R., Ed.; Consell de Collegis d’Infermeres i Infermers de Catalunya Rosselló: Barcelona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, D. The maternity services and becoming a midwife in Ireland. In Maternity Care in Different Countries. Midwife’s Contribution, 1st ed.; Escuriet, R., Ed.; Consell de Collegis d’Infermeres i Infermers de Catalunya Rosselló: Barcelona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gasser, L.; Daly, D.; Benoit Truong Canh, M. The Profession of Midwives in Croatia. Available online: http://www.hupp.hr/baza/upload/File/midwife%20report1_eng.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Sahakyan, S.; Aslanyan, L.; Hovhannisyan, S.; Poghosyan, K.; Petrosyan, V. An Evaluation of Midwifery Education System in Armenia. Armenia: American University of Armenia. Available online: https://chsr.aua.am/files/2019/03/An-Evaluation-of-Midwifery-Education-System-in-Armenia_2019.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Western Pacific Region Nursing and Midwifery Databank. Country: Fiji. Available online: http://www.wpro.who.int/hrh/about/nursing_midwifery/db_fiji_2013.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Atkin, L.C.; Keith-Brown, K.; Rees, M.W.; Sesia, P. Midwifery in Mexico; Management Sciences for Health: Medford, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Public Interest Incorporated Foundation. Japan Society of Midwifery Education. Available online: http://www.zenjomid.org/img/2015icm.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Australian College of Midwives. FAQ-Is Midwifery for Me? Available online: https://www.midwives.org.au/faq-midwifery-me (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- The Royal College of Midwives. How to Become a Midwife? Available online: https://www.rcm.org.uk/learning-and-career/becoming-a-midwife (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- New Zealand College of Midwives. Regulation. Available online: https://www.midwife.org.nz/midwives/midwifery-in-new-zealand/regulation/ (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- American College of Nurse-Midwives. Definition of Midwifery and Scope of Practice of Certified Nurse-Midwives and Certified Midwives. Available online: https://www.midwife.org/acnm/files/ACNMLibraryData/UPLOADFILENAME/000000000266/Definition%20of%20Midwifery%20and%20Scope%20of%20Practice%20of%20CNMs%20and%20CMs%20Feb%202012.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- American College of Nurse-Midwives. Information for Midwives Educated Abroad. Available online: http://www.midwife.org/Foreign-Educated-Nurse-Midwives (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- American College of Nurse-Midwives. Comparison of Certified Nurse-Midwives, Certified Midwives, Certified Professional Midwives Clarifying the Distinctions Among Professional Midwifery Credentials in the US. Available online: http://www.midwife.org/acnm/files/ccLibraryFiles/FILENAME/000000006807/FINAL-ComparisonChart-Oct2017.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- American College of Nurse-Midwives. Become a Midwife. Available online: http://www.midwife.org/Become-a-Midwife (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Urbánková, E.; Hospodková, P.; Severová, L. The Assessment of the Quality of Human Resources in the Midwife Profession in the Healthcare Sector of the Czech Republic. Economies 2018, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Natan, M.B.; Ehrenfeld, M. Nursing and midwifery education, practice, and issues in Israel. Nurs. Health Sci. 2011, 13, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattern, E.; Lohmann, S.; Ayerle, G.M. Experiences and wishes of women regarding systemic aspects of midwifery care in Germany: A qualitative study with focus groups. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mivšek, P.; Pahor, M.; Hlebec, V.; Hundley, V. How do midwives in Slovenia view their professional status? Midwifery 2015, 31, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H. Improving the standards of midwifery education and practice and extending the role of a midwife in Korean women and children’s health care. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2003, 33, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lillo, E.; Oyarzo, S.; Carroza, J.; Román, A. Midwifery in Chile, A Successful Experience to Improve Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health: Facilitators & Challenges. J. Asian Midwives 2016, 3, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, D. Midwifery in Northern Belize. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2001, 46, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Public Service (FPS) Health, Food Chain Safety and Environment. Regulated Healthcare Professions in Belgium. Available online: https://www.health.belgium.be/en/health/taking-care-yourself/patient-related-themes/cross-border-health-care/healthcare-providers-0 (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Ministry of Health. Licence for Independent Practice of Nursing and Midwifery. Available online: http://eugo.gov.si/en/permits/permit/12580/showPermit/ (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Ministry of Health. Entry in the Register of Nursing and Midwifery Services. Available online: http://eugo.gov.si/en/permits/permit/12579/showPermit/ (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Ministry of Public Health. Healthcare Practitioners Registration & Licensing. Available online: https://www.moph.gov.qa/health-services/Pages/healthcare-practitioners-registration-n-licensing.aspx (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Ministry of Public Health. Information about the Qatar Council for Healthcare Practitioners (QCHP). Available online: https://www.prometric.com/test-takers/search/schq2aspx (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Ministry of Health Government of Grenada. Careers in Nursing: Midwifery. Available online: http://www.health.gov.gd/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=189&Itemid=486&lang=en (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Federal Public Service (FPS) Health, Food Chain Safety and Environment. Healthcare Providers. Available online: https://www.health.belgium.be/en/health/taking-care-yourself/patient-related-themes/cross-border-health-care/healthcare-providers (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- UAE Nursing and Midwifery Council. UAE Nursing and Midwifery Education Standards; UAE Nursing and Midwifery Council: Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nursing and Midwifery Board of Ireland. Requirements and Standards for the Midwife Registration Education Programme, 3rd ed.; Nursing and Midwifery Board of Ireland: Dublin, Ireland, 2005; Available online: https://www.nmbi.ie/nmbi/media/NMBI/Requirements-and-Standards-for-the-Midwife-Registration-Education-Programme-3rd-ed.pdf?ext=.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Nursing Midwifery Board of Ireland. Midwife Post-RGN Registration: Standards and Requirements. Available online: https://www.nmbi.ie/Education/Standards-and-Requirements/Midwife-Post-RGN (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Nursing and Midwifery Council. Standards for Competence for Registered Midwives; Nursing and Midwifery Council: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Regulatory Authority. Healthcare Professional Licensing Standards: Nurses 2017. Available online: http://www.nhra.bh/MediaHandler/GenericHandler/documents/departments/HCP/Qualifications_Requirements/HCP_Standards_Licensing%20requirements%20for%20nurses_v1.0_2017.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Weiss, S.; Ditto, M.; Füszl, S.; Lanske, P.; Lust, A.; Oberleitner-Tschan, C.; Wenda, S. Healthcare Professions in Austria. Available online: https://www.sozialministerium.at/siteEN/Health/Healthcare_Professions/Brochure_Healthcare_Professions_in_Austria (accessed on 5 March 2019).

- Beňušová, K.; Hozlárová, M.; Menďanová, Z.; Nagy, M.; Slezáková, Z.; Šablová, V.; Závodná, V. Education of Healthcare Professionals in the Slovak Republic; Ministry of Health of the Slovak Republic: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Qatar Council for Health Practitioners. Nursing Regulations in the State of Qatar. Available online: http://www.qchp.org.qa/en/Documents/Nursing%20Regulations%20in%20the%20State%20of%20Qatar.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Qatar Council of Health Practitioners. Circular No. (12/2016). Available online: http://www.qchp.org.qa/en/QCHPCirculars/Circular%20(12-2016)%20-%20Eng.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Jahlan, I. Perspectives on Birthing Services in Saudi Arabia; Monash University: Melbourne, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zondag, L.; Cadée, F.; de Geus, M. Midwifery in Netherlands. Available online: https://www.knov.nl/serve/file/knov.nl/knov_downloads/526/file/Midwifery_in_The_Netherlands_versie_2017.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Ministry of Health Malaysia. Human Resources for Health, Country Profiles 2015 Malaysia; Planning Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2016; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Kruk, M.E.; Gage, A.D.; Arsenault, C.; Jordan, K.; Leslie, H.H.; Roder-DeWan, S.; Adeyi, O.; Barker, P.; Daelmans, B.; Doubova, S.V.; et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: Time for a revolution. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1196–e1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education for Universal Health Coverage 2030: Framework for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, K.; Birks, M.; Al-Motlaq, M.; Davis, J.; Miles, M.; Bailey, C. Responding to a rural health workforce shortfall: Double degree preparation of the nurse midwife. Aust. J. Rural Health 2010, 18, 210–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfreðsdóttir, H.; Nieuwenhuijze, M.J. Midwifery education: Challenges for the future in a dynamic environment. Midwifery 2018, 59, 78–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Fact Sheet: The Impact of Education on Nursing Practice; American Association of Colleges of Nursing: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.H. Differences in the performances of baccalaureate, associate degree, and diploma nurses: A meta-analysis. Res. Nurs. Health 1988, 11, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H.; Sloane, D.M.; Bruyneel, L.; Van den Heede, K.; Griffiths, P.; Busse, R.; Diomidous, M.; Kinnunen, J.; Kózka, M.; Lesaffre, E. Nurse staffing and education and hospital mortality in nine European countries: A retrospective observational study. Lancet 2014, 383, 1824–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cho, E.; Sloane, D.M.; Kim, E.-Y.; Kim, S.; Choi, M.; Yoo, I.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Aiken, L.H. Effects of nurse staffing, work environments, and education on patient mortality: An observational study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Estabrooks, C.A.; Midodzi, W.K.; Cummings, G.G.; Ricker, K.L.; Giovannetti, P. The impact of hospital nursing characteristics on 30-day mortality. Nurs. Res. 2005, 54, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutney-Lee, A.; Sloane, D.M.; Aiken, L.H. An increase in the number of nurses with baccalaureate degrees is linked to lower rates of postsurgery mortality. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Romp, C.R.; Kiehl, E.M.; Bickett, A.; Bledsoe, S.F.; Brown, D.S.; Eitel, S.B.; Wall, M.P. Motivators and barriers to returning to school: RN to BSN. J. Nurses Prof. Dev. 2014, 30, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finch, D.J. Degree-level education is an essential part of modern health care. Nurs. Stand. 2016, 30, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swindells, C.; Willmott, S. Degree vs diploma education: Increased value to practice. Br. J. Nurs. 2003, 12, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.R. Critical thinking ability and clinical decision-making skills among senior nursing students in associate and baccalaureate programmes in Korea. J. Adv. Nurs. 1998, 27, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muoni, T. Decision-making, intuition, and the midwife: Understanding heuristics. Br. J. Midwifery 2012, 20, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S.; Abdullah, K.L.; Subramanian, P.; Bachmann, R.T.; Ong, S.L. An integrated review of the correlation between critical thinking ability and clinical decision-making in nursing. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 4065–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, L.-M.; Aiken, L.H.; Sloane, D.M.; Liu, K.; He, G.-P.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, X.-L.; Li, X.-H.; Li, X.-M.; Liu, H.-P. Hospital nursing, care quality, and patient satisfaction: Cross-sectional surveys of nurses and patients in hospitals in China and Europe. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The U.S. Nursing Workforce: Trends in Supply and Education; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roets, L.; Botma, Y.; Grobler, C. Scholarship in nursing: Degree-prepared nurses versus diploma-prepared nurses. Health SA Gesondheid 2016, 21, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sackett, D.L.; Rosenberg, W.M.; Gray, J.M.; Haynes, R.B.; Richardson, W.S. Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 1996, 312, 71–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Facilitating Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Midwifery in the WHO European Region; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- De Leo, A.; Bayes, S.; Geraghty, S.; Butt, J. Midwives’ use of best available evidence in practice: An integrative review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 4225–4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lai, N.M.; Teng, C.L.; Lee, M.L. The place and barriers of evidence based practice: Knowledge and perceptions of medical, nursing and allied health practitioners in Malaysia. BMC Res. Notes 2010, 3, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Homer, C.S.; Friberg, I.K.; Dias, M.A.B.; ten Hoope-Bender, P.; Sandall, J.; Speciale, A.M.; Bartlett, L.A. The projected effect of scaling up midwifery. Lancet 2014, 384, 1146–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisawad, K. Role of Midwife in Preconception Care. Songklanagarind J. Nurs. 2017, 37, 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, N.; Kai, J.; Qureshi, N. The effects of preconception interventions on improving reproductive health and pregnancy outcomes in primary care: A systematic review. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2016, 22, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yngyknd, S.G.; Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S.; Babapour, J.; Mirghafourvand, M. The effect of counselling on preconception lifestyle and awareness in Iranian women contemplating pregnancy: A randomized control trial. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018, 31, 2538–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suruhanjaya Perkhidmatan Awam Malaysia. Jururawat Masyarakat Gred U19. 2020. Available online: https://www.spa.gov.my/spa/laman-utama/gaji-syarat-lantikan-deskripsi-tugas/spm-svm-skm-sijil/jururawat-masyarakat-gred-u19 (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Midwives Act 1966 (Amended 2006); The Commissioner of Law Revision, Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2006.

- Rooney, A.; van Ostenberg, P. Licensure, Accreditation, and Certification: Approaches to Health Services Quality; Centre for Human Services: Bethesda, MD, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, C.H. Perceived effects of specialty nurse certification: A review of the literature. AORN J. 2009, 89, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cary, A.H. Certified registered nurses: Results of the study of the certified workforce. Am. J. Nurs. 2001, 101, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, D.K.; Cramer, E.; Potter, C.; Gatua, M.W.; Stobinski, J.X. The relationship between direct-care RN specialty certification and surgical patient outcomes. AORN J. 2014, 100, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, K.; Leatherman, S. Does certification improve medical standards? BMJ 2006, 333, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bradshaw, C.; Tighe, S.M.; Doody, O. Midwifery students’ experiences of their clinical internship: A qualitative descriptive study. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 68, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lukasse, M.; Henriksen, L. Norwegian midwives’ perceptions of their practice environment: A mixed methods study. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 1559–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schytt, E.; Waldenström, U. How well does midwifery education prepare for clinical practice? Exploring the views of Swedish students, midwives and obstetricians. Midwifery 2013, 29, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.J.; Fraser, D.M. ‘Sink or swim’: The experience of newly qualified midwives in England. Midwifery 2011, 27, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Putten, D. The lived experience of newly qualified midwives: A qualitative study. Br. J. Midwifery 2008, 16, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, J.; Green, S. Development of a preceptorship programme. Br. J. Midwifery 2003, 11, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enrico, N.B. The lived experiences of mentoring nurses in Malaysia. Nurse Media J. Nurs. 2011, 1, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pairman, S.; Dixon, L.; Tumilty, E.; Gray, E.; Campbell, N.; Calvert, S.; Kensington, M. The Midwifery First Year of Practice programme: Supporting New Zealand midwifery graduates in their transition to practice. N. Z. Coll. Midwives J. 2016, 52, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dixon, L.; Calvert, S.; Tumilty, E.; Kensington, M.; Gray, E.; Lennox, S.; Campbell, N.; Pairman, S. Supporting New Zealand graduate midwives to stay in the profession: An evaluation of the Midwifery First Year of Practice programme. Midwifery 2015, 31, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıcı, S. Midwifery students’ demographic characteristics and the effect of clinical education on preparation for professional life in Turkey. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2010, 10, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Source | Title | Type of Document | Document ID | Country | Qualification | MMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ministry of Welfare, 2012 [38] | Regulation on the education, rights and obligations of midwives and criteria for granting of licences and specialist licences, No. 1089/2012 | Law document | 44 | Iceland | Degree in Nursing + Postgraduate in Midwifery | 3 |

| Urbánková et al., 2018 [67] | The Assessment of the Quality of Human Resources in the Midwife Profession in the Healthcare Sector of the Czech Republic | Published article | 10 | Czech Republic | Degree in Midwifery | 4 |

| Emons & Luiten, 2001 [49] | Midwifery in Europe: An inventory in fifteen EU-member states | Assessment report | 26 | Sweden | Degree in Nursing + Postgraduate in Midwifery | 4 |

| Weiss, et al., 2017 [86] | Healthcare Professions in Austria 2017 | Government document | 50 | Austria | Degree in Midwifery | 4 |

| Emons & Luiten, 2001 * [49] | Midwifery in Europe: An inventory in fifteen EU-member states | Assessment report | 26 | |||

| Ruiz-Berdún, 2016 [50] | Chapter 1: The competences of midwives in Spain over time in Maternity care in different countries Midwife’s contribution | Assessment report | 4 | Spain | Diploma in Nursing + Post-nursing in Midwifery | 5 |

| Leon-Larios, 2016 [51] | Chapter 2: The current situation of midwives in Spain in Maternity care in different countries: Midwife’s contribution | Assessment report | 4 | |||

| Natan & Ehrenfeld, 2011 [68] | Nursing and midwifery education, practice, and issues in Israel | Published article | 14 | Israel | Degree in Nursing +Postgraduate in Midwifery | 5 |

| Japanese Nursing Association, 2018 [52] | Midwifery in Japan | Assessment report | 25 | Japan a | Diploma in Nursing + Post-nursing in Midwifery | 5 |

| Act on Public Health Nurses, Midwives, and Nurses, Act No.2013 1948 [39] | Act on Public Health Nurses, Midwives, and Nurses, Act No.2013 1948 | Law document | 38 | |||

| Public Interest Incorporated Foundation [59] | Japanese Society of Midwifery Education: How to become a midwife in Japan | Midwifery association web page | 63 | |||

| Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia, 2017 [27] | Registration Standards | Governing body web page | 15 | Australia | Degree in Midwifery | 6 |

| Australian Nursing and Midwifery Accreditation Council, 2014 [28] | Midwife Accreditation Standards 2014 | Governing body web page | 29 | |||

| Australian College of Midwives, 2019 [60] | Is Midwifery for Me? | Midwifery association web page | 59 | |||

| Beňušová et al., 2006 [87] | Education of healthcare professionals in the Slovak Republic | Government document | 21 | Slovakia | Degree in Midwifery | 6 |

| UAE Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2013 [81] | UAE Nursing and Midwifery Education Standards | Standards | 47 | United Arab Emirates | Degree in Midwifery | 6 |

| Mattern, et al., 2017 [69] | Experiences and wishes of women regarding systemic aspects of midwifery care in Germany: a qualitative study with focus groups | Published article | 45 | Germany | Degree in Midwifery | 6 |

| Emons & Luiten, 2001 * [49] | Midwifery in Europe: An inventory in fifteen EU-member states | Assessment report | 26 | |||

| Zondag, et al., 2017 [91] | Midwifery in the Netherlands 2017 | Assessment report | 37 | Netherlands b | Degree in Midwifery | 7 |

| Emons & Luiten, 2001 * [49] | Midwifery in Europe: An inventory in fifteen EU-member states | Assessment report | 26 | |||

| Federal Public Service (FPS) Health, Food Chain Safety and Environment, 2016 [74] | Regulated healthcare professions in Belgium | Government web page | 64 | Belgium | Degree in Midwifery | 7 |

| Federal Public Service (FPS) Health, Food Chain Safety and Environment, 2016 [80] | Healthcare providers | Government web page | 41 | |||

| Emons & Luiten, 2001 * [49] | Midwifery in Europe: An inventory in fifteen EU-member states | Assessment report | 26 | |||

| Beeckman K., & Reyns M., 2016 ** [53] | Chapter 6: Midwifery in Belgium in Midwifery Care in Different Countries | Assessment report | 4 | |||

| Nursing and Midwifery Board of Ireland, 2005 [82] | Requirements and Standards for the Midwife Registration Education Programme Third Edition | Standards | 17 | Ireland | Degree in Midwifery | 8 |

| Nursing and Midwifery Board of Ireland [29] | Registration | Governing body web page | 18 | |||

| Nursing and Midwifery Board of Ireland [30] | Careers in Nursing and Midwifery: Where to study to become a nurse or midwife? | Governing body web page | 19 | |||

| Nursing and Midwifery Board of Ireland [83] | Midwife Post-RGN Registration: Standards and requirements | Standards | 20 | |||

| Emons & Luiten, 2001 * [49] | Midwifery in Europe: An inventory in fifteen EU-member states | Assessment report | 26 | |||

| Daly D., 2016 ** [54] | Chapter 5: The maternity services and becoming a midwife in Ireland in Midwifery Care in Different Countries | Assessment report | 4 | |||

| Gasser et al., 2008 [55] | The profession of midwives in Croatia | Assessment report | 60 | Croatia | Degree in Midwifery | 8 |

| Midwifery Act, 2008 [40] | Midwifery Act (consolidated text, OG 120/08, 145/10) | Law document | 27 | |||

| The Royal College of Midwives [61] | How to become a midwife? | Midwifery association web page | 2 | United Kingdom | Degree in Midwifery | 9 |

| Nursing and Midwifery Council [84] | Standards for competence for registered midwives | Standards | 5 | |||

| Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2019 [31] | Becoming a midwife | Governing body web page | 51 | |||

| Ministry of Health, 2017 [75] | Licence for independent practice of nursing and midwifery services | Government web page | 33 | Slovenia | Degree in Midwifery | 9 |

| Ministry of Health, 2017 [76] | Entry in the register of nursing and midwifery service | Government web page | 46 | |||

| Mivšek et al., 2015 [70] | How do midwives in Slovenia view their professional status? | Published article | 40 | |||

| Health Care Professions Act, Chapter 464, 2003 [41] | Health Care Professions Act, Chapter 464, 2003 | Law document | 43 | Malta | Diploma in Midwifery | 9 |

| Nurses and Midwives Act Chapter 209, 2012 Revised Edition [42] | Nurses and Midwives Act Chapter 209, 2012 Revised Edition | Law document | 16 | Singapore | Diploma in Nursing + Post-nursing in Midwifery | 10 |

| Singapore Nursing Board, 2019 [32] | Local graduates | Governing body web page | 32 | |||

| Midwifery Council of New Zealand [33] | What does it take to qualify as a midwife? | Governing body web page | 1 | New Zealand | Degree in Midwifery | 11 |

| New Zealand College of Midwives [62] | Regulation | Midwifery association web page | 8 | |||

| Midwifery Council of New Zealand [34] | Maintaining competence | Governing body web page | 55 | |||

| Midwifery Council of New Zealand [35] | Becoming Registered to Practise | Governing body web page | 65 | |||

| Lee, 2003 [71] | Improving the Standards of Midwifery Education and Practice and Extending the Role of a Midwife in Korean Women and Children’s Health Care | Published article | 39 | Korea | Unspecified Nursing Education + Midwifery Education | 11 |

| Jahlan, 2016 [90] | Perspectives on Birthing Services in Saudi Arabia | Doctoral thesis | 9 | Saudi Arabia | Degree in Nursing + Master’s in Midwifery | 12 |

| American College of Nurse-Midwives, 2011 [63] | Definition of Midwifery and Scope of Practice of Certified Nurse–Midwives and Certified Midwives | Midwifery association web page | 11 | United States c | Degree in Nursing + Master’s in Midwifery | 13 |

| American College of Nurse-Midwives [64] | Information for Midwives Educated Abroad | Midwifery association web page | 23 | |||

| Midwifery Education and Accreditation Council, 2019 [36] | Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) | Governing body web page | 31 | |||

| American College of Nurse Midwives [65] | Comparison of Certified Nurse–Midwives, Certified Midwives, Certified Professional Midwives Clarifying the Distinctions Among Professional Midwifery Credentials in the US | Midwifery association web page | 48 | |||

| American College of Midwives [66] | Become a Midwife | Midwifery association web page | 52 | |||

| North American Registry of Midwives [37] | How to become a CPM | Governing body web page | 56 | |||

| Qatar Council for Health Practitioners [88] | Nursing Regulations in the state of Qatar | Government document | 12 | Qatar | Degree in Midwifery | 13 |

| Qatar Council for Health Practitioners, 2016 [89] | Circular No. (12/2016) | Government document | 49 | |||

| Ministry of Public Health, 2017 [77] | Healthcare Practitioners Registration & Licensing | Government web page | 57 | |||

| Ministry of Public Health, 2018 [78] | Information about the Qatar Council for Health Practitioners (QCHP) | Government web page | 67 | |||

| Lebanese Order of Midwives, 2018 [43] | Lebanese Order of Midwives, 2018 | Law document | 34 | Lebanon | Degree in Midwifery | 15 |

| National Health Regulatory Authority, 2017 [85] | Healthcare Professional Licensing Standards: Nurses 2017 | Standards | 42 | Bahrain d | Diploma in Nursing & Midwifery | 15 |

| Law on Regulated Professions and Recognition of Professional Qualifications, 2001 [44] | Law on Regulated Professions and Recognition of Professional Qualifications, 2001 | Law document | 36 | Latvia | Diploma in Midwifery | 18 |

| Nursing and Midwifery Profession Act B.E. 2528, 1985 [45] | Nursing and Midwifery Profession Act B.E. 2528, 1985 | Law document | 13 | Thailand | Certificate | 20 |

| Lillo et al., 2016 [72] | Midwifery in Chile, A Successful Experience to Improve Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health: Facilitators & Challenges | Published article | 54 | Chile | Degree in Midwifery | 22 |

| Sahakayan et al., 2019 [56] | An Evaluation of Midwifery Education System in Armenia | Assessment report | 53 | Armenia | Diploma in Midwifery | 25 |

| Ministry of Health Government of Grenada, 2016 [79] | Careers in Nursing: Midwifery | Government web page | 28 | Grenada | Unspecified Nursing Education + Midwifery Education | 27 |

| Chapter 194 Midwives Act, 2003 [46] | Chapter 194 Midwives Act, 2004 | Law document | 35 | |||

| Boyer, 2001 [73] | Midwifery in Northern Belize | Published article | 24 | Belize e | Certificate | 28 |

| Nurses and Midwives Registration Act, Chapter 321, 2003 [47] | Nurses and Midwives Registration Act, Chapter 321, 2003 | Law document | 62 | |||

| Western Pacific Region Nursing and Midwifery Databank, 2013 [57] | Western Pacific Region Nursing and Midwifery Databank. Country: Fiji | Assessment report | 61 | Fiji | Diploma in Nursing + Post-nursing in Midwifery | 30 |

| Medical Ordinance, Chapter 113 [48] | Medical Ordinance, Chapter 113 | Law document | 30 | Sri Lanka | Certificate | 30 |

| Atkin et al., 2017 [58] | Midwifery in Mexico | Assessment report | 58 | Mexico f | Certificate | 38 |

| Country | Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) | Requirements to Practise as a Recognised Midwife * | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing Education | National Nursing Examination | Registration as a Nurse | Licence in Nursing | Work Experience | Supervised In-Service Training | National Midwifery Examination | Registration as a Midwife | Licence in Midwifery | |||

| Iceland | 3 | ● | ● | ||||||||

| Czech Republic | 4 | No information available | |||||||||

| Sweden | 4 | ● | ● | Nurse (6 months) | ● | ||||||

| Austria | 4 | ● | |||||||||

| Spain | 5 | ● | |||||||||

| Israel | 5 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Japan a | 5 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Australia | 6 | ● | |||||||||

| Slovakia | 6 | ● | |||||||||

| United Arab Emirates | 6 | ● | ● | ||||||||

| Germany | 6 | ● | Not required | ||||||||

| Netherlands b | 7 | ● | |||||||||

| Belgium | 7 | ● | ● | ||||||||

| Ireland | 8 | ● | |||||||||

| Croatia | 8 | ● | ● | ||||||||

| United Kingdom | 9 | ● | |||||||||

| Slovenia | 9 | ● | ● | ||||||||

| Malta | 9 | ● | ● | ||||||||

| Singapore | 10 | ● | ● ** | ● | ● | ● *** | |||||

| New Zealand | 11 | ● | ● | ||||||||

| Korea | 11 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||

| Saudi Arabia | 12 | ● | ● | ● | |||||||

| United States c | 13 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Qatar | 13 | ● | ● | ● | |||||||

| Lebanon | 15 | ● | |||||||||

| Bahrain d | 15 | ● | |||||||||

| Latvia | 18 | ● | ● | ||||||||

| Thailand | 20 | ● | ● | ● | |||||||

| Chile | 22 | No information available | |||||||||

| Armenia | 25 | No information available | |||||||||

| Grenada | 27 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||

| Belize e | 28 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||

| Fiji | 30 | ● | ● | Nurse (2 years) | ● | ||||||

| Sri Lanka | 30 | ● | |||||||||

| Mexico f | 38 | No information available | |||||||||

| Malaysia | Community Nurse | 40 | ● | ● | |||||||

| Nurse-Midwife | ● | ● | ● | Nurse (2 years) | ● | ● | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Md. Sharif, S.; Yap, W.S.; Fun, W.H.; Yoon, E.L.; Abd Razak, N.F.; Sararaks, S.; Lee, S.W.H. Midwifery Qualification in Selected Countries: A Rapid Review. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11, 859-880. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep11040080

Md. Sharif S, Yap WS, Fun WH, Yoon EL, Abd Razak NF, Sararaks S, Lee SWH. Midwifery Qualification in Selected Countries: A Rapid Review. Nursing Reports. 2021; 11(4):859-880. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep11040080

Chicago/Turabian StyleMd. Sharif, Shakirah, Wuan Shuen Yap, Weng Hong Fun, Ee Ling Yoon, Nur Fadzilah Abd Razak, Sondi Sararaks, and Shaun Wen Huey Lee. 2021. "Midwifery Qualification in Selected Countries: A Rapid Review" Nursing Reports 11, no. 4: 859-880. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep11040080

APA StyleMd. Sharif, S., Yap, W. S., Fun, W. H., Yoon, E. L., Abd Razak, N. F., Sararaks, S., & Lee, S. W. H. (2021). Midwifery Qualification in Selected Countries: A Rapid Review. Nursing Reports, 11(4), 859-880. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep11040080