Place of Work and Level of Satisfaction with the Lives of Polish Nurses

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

The Estimation Method and the Following Statistical Methods Were Used

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Group

3.2. Findings

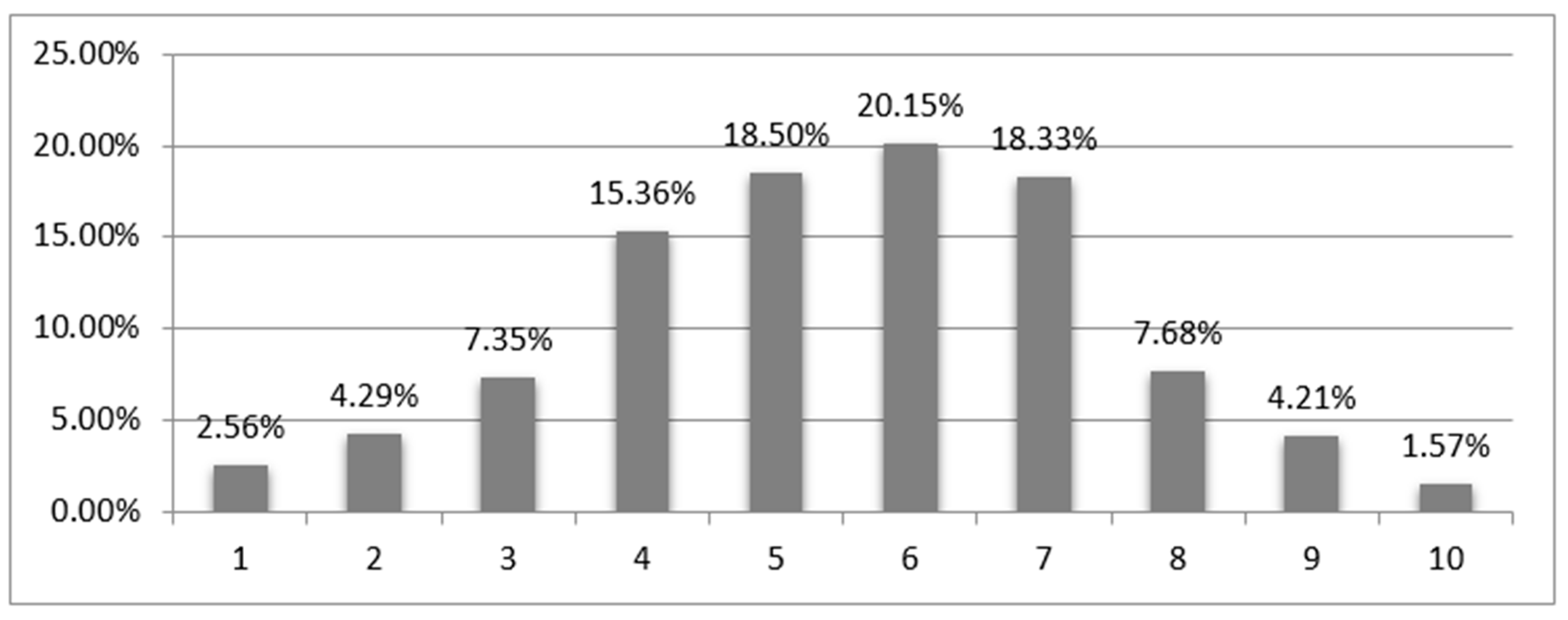

3.3. Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) by Variables for All Respondents (n = 1211)

3.4. Differences between Nurses Working in Primary Health Care, Outpatient Specialist Care, or in Hospital and the Level of Life Satisfaction in Individual Categories of Independent Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global strategy on occupational health for all: The way to health at work. In Proceedings of the Recommendation of the Second Meeting of the WHO Collaborating Centres in Occupational Health, Beijing, China, 11–14 October 1994.

- Global Strategic Directions for Strengthening Nursing and Midwifery 2016–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Tomaszewska, K.; Majchrowicz, B. Professional burnout of nurses employed in non-invasive treatment wards. J. Educ. Health Sport 2018, 9, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar]

- Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Ortega-Campos, E.M.; Cañadas, G.R.; Albendín-García, L.; De la Fuente-Solana, E.I. Prevalence of burnout syndrome in oncology nursing: A meta-analytic study. Psycho Oncol. 2018, 27, 1426–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, E.; Ramirez-Baena, L.; la Fuente-Solana, D.; Emilia, I.; Vargas, C.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L. Gender, marital status, and children as risk factors for burnout in nurses: A meta-analytic study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2102. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Praena, J.; Ramirez-Baena, L.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Cañadas, G.R.; De la Fuente, E.I. Levels of burnout and risk factors in medical area nurses: A meta-analytic study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2800. [Google Scholar]

- Kanadys, K.; Rogowska, J.; Lewicka, M.; Wiktor, H. Satysfakcja z życia kobiet ciężarnych. Med. Ogólna i Nauki o Zdrowiu 2015, 21, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jaracz, K. Sposoby ujmowania i pomiaru jakości życia. Próba kategoryzacji. Piel. Polskie 2001, 2, 219–226. [Google Scholar]

- Juczyński, Z. Narzędzia Pomiaru w Promocji i Psychologii Zdrowia; Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Persnal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kunecka, D.; Kamińska, M.; Karakiewicz, B. Analiza czynników wpływających na zadowolenie z wykonywanej pracy w grupie zawodowej pielęgniarek. Badanie wstępne. Probl. Piel. 2007, 15, 192–196. [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy, M.J. Materialism and quality of life. Soc. Indic. Res. 1998, 43, 227–260. [Google Scholar]

- Kliszcz, J.; Nowicka-Sauer, K.; Trzeciak, B.; Sadowska, A. Poziom lęku, depresji i agresji u pielęgniarek, a ich satysfakcja z życia i z pracy zawodowej. Med. Pracy 2004, 55, 461–467. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowska, K.O.; Wysokiński, M.; Fidecki, W.; Snopek, E. Life satisfaction of Lublin nurses. J. Educ. Health Sport 2017, 7, 142–153. [Google Scholar]

- Wysokiński, M.; Fidecki, W.; Walas, L.; Ślusarz, R.; Sienkiewicz, Z.; Sadurska, A.; Kachaniuk, H. Satysfakcja z życia polskich pielęgniarek. Probl. Piel. 2009, 17, 167–172. [Google Scholar]

- Piotrkowska, R.; Jarzynkowski, P.; Książek, J.; Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W. Satisfaction with life of oncology nurses in Poland. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2019, 66, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghazwin, M.Y.; Kavian, M.; Ahmadloo, M.; Jarchi, A.; Javadi, S.G.; Latifi, S.; Ghajarzadeh, M. The association between life satisfaction and the extent of depression, anxiety and stress among Iranian nurses: A multicenter survey. Iran J. Psychiatry 2016, 11, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Hwang, S.; Kim, J.; Daly, B. Predictors of life satisfaction of Korean nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 48, 632–641. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, W.E.W.; Nordin, M.S.; Omar, A.; Ismail, I. Social support, work-family enrichment and life satisfaction among married nurses in health service. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Hum. 2011, 1, 150. [Google Scholar]

- Kupcewicz, E.; Szczypiński, W.; Kędzia, A. Satysfakcja z życia w kontekście życia zawodowego pielęgniarek Satisfaction with life in the context of professional life of nurses. Piel. Zdr. Publ. 2018, 8, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Swatowska, A.; Fidecki, W.; Wysokiński, M. Wybrane aspekty oceny satysfakcji z życia pielęgniarek oddziałów neurologicznych. J. Neur. Neurosurg. Nurs. 2019, 8, 157–161. [Google Scholar]

- Pietraszek, A.; Charzyńska-Gula, M.; Dobrowolska, B.; Stanisławek, A.; Łuczyk, M. The life satisfaction of Polish nurses at the retirement age. J. Educ. Health Sport 2016, 6, 333–344. [Google Scholar]

- Lewko, J.; Misiak, B.; Sierżantowicz, R. The Relationship between Mental Health and the Quality of Life of Polish Nurses with Many Years of Experience in the Profession: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1798. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowska, E.; Jakubowski, K.; Cipora, E. Satysfakcja z życia chorych z cukrzycą. Probl. Hig. Epid. 2010, 91, 308–313. [Google Scholar]

- Dziąbek, E.; Dziuk, U.; Bieniek, J.; Brończyk-Puzoń, A.; Kowolik, B.; Borgosz, J. Ocena satysfakcji życiowej w wybranej grupie pielęgniarek i położnych członków Beskidzkiej Okręgowej Izby Pielęgniarek i Położnych w Bielsku-Białej–doniesienie wstępne. Probl. Piel. 2015, 23, 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowska, A.; Żuralska, R.; Mziray, M. Assessment of life satisfaction among nurses employed in the Medical University of Gdańsk and paramedics from Pomeranian Voivodeship. Piel. Zdr. Publ. 2017, 7, 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- Caro, M.M.; San-Martín, M.; Delgado-Bolton, R.; Vivanco, L. Empathy, loneliness, burnout, and life satisfaction in Chilean nurses of palliative care and homecare services. Enferm. Clín. 2017, 27, 379–386. [Google Scholar]

| Independent Variables | Categories | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Up to 30 years | 220 | 18.17 |

| From 31–40 years old | 165 | 13.63 | |

| From 41–50 years old | 393 | 32.45 | |

| From 51–60 years old | 388 | 32.04 | |

| Over 60 years | 45 | 3.72 | |

| Place of residence | Town | 661 | 54.58 |

| Village | 550 | 45.42 | |

| Work experience as a nurse | From 1–5 years | 201 | 16.60 |

| From 6–10 years | 111 | 9.17 | |

| From 11–15 years | 104 | 8.59 | |

| From 16–24 years | 213 | 17.59 | |

| Over 25 years | 582 | 48.06 | |

| Education | Secondary nursing education | 583 | 48.14 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 399 | 32.95 | |

| Master’s degree | 229 | 18.91 | |

| Additional qualifications | No | 942 | 77.79 |

| Yes | 269 | 22.21 | |

| Place of work | Primary health care (PHC) | 414 | 34.19 |

| Hospital (H) | 405 | 33.44 | |

| Outpatient specialist care (OSC) | 392 | 32.37 | |

| Held position | Not managerial | 1158 | 95.62 |

| Managerial | 53 | 4.38 | |

| Having a family/motherhood experience | No | 158 | 13.05 |

| Yes | 1053 | 86.95 | |

| Self-assessment of the material situation | Revenues lower than expenses | 209 | 17.26 |

| Revenues equal to expenses | 907 | 74.90 | |

| Revenues higher than expenses | 95 | 7.84 | |

| Self-assessment of health | Very good | 263 | 21.72 |

| Good | 498 | 41.12 | |

| Average | 384 | 31.71 | |

| Disappointing | 66 | 5.45 |

| SWLS/Items | Item No 1 | Item No 2 | Item No 3 | Item No 4 | Item No 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I totally disagree | n | 99 | 68 | 21 | 31 | 106 |

| % | 8.2 | 5.6 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 8.8 | |

| I do not agree | n | 169 | 188 | 45 | 106 | 190 |

| % | 14.0 | 15.5 | 3.7 | 8.8 | 15.7 | |

| Rather disagree | n | 250 | 293 | 99 | 155 | 202 |

| % | 20.6 | 24.2 | 8.2 | 12.8 | 16.7 | |

| Neither agree nor agree | n | 363 | 299 | 237 | 250 | 228 |

| % | 30.0 | 24.7 | 19.6 | 20.6 | 18.8 | |

| I rather agree | n | 222 | 258 | 446 | 386 | 286 |

| % | 18.3 | 21.3 | 36.8 | 31.9 | 23.6 | |

| I agree | n | 91 | 79 | 302 | 225 | 150 |

| % | 7.5 | 6.5 | 24.9 | 18.6 | 12.4 | |

| Totally agree | n | 17 | 26 | 61 | 58 | 49 |

| % | 1.4 | 2.1 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 4.0 | |

| Average | 3.64 | 3.69 | 4.81 | 4.45 | 3.86 | |

| SD | 1.41 | 1.39 | 1.25 | 1.41 | 1.63 | |

| Variance | 1.99 | 1.94 | 1.55 | 2.00 | 2.66 | |

| Independent Variables | Place of Work | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHC | H | OSC | |||||

| Age: Less than 30 years | Level of satisfaction with life | low | n | 11 | 14 | 9 | 0.0030 |

| % | 29.7 | 9.4 | 26.5 | ||||

| average | n | 15 | 52 | 10 | |||

| % | 40.5 | 34.9 | 29.4 | ||||

| high | n | 11 | 83 | 15 | |||

| % | 29.7 | 55.7 | 44.1 | ||||

| Total | 37 | 149 | 34 | ||||

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||||

| Age: Over 50 years | Level of satisfaction with life | low | n | 61 | 21 | 58 | 0.0362 |

| % | 33.9 | 24.1 | 34.9 | ||||

| average | n | 80 | 33 | 72 | |||

| % | 44.4 | 37.9 | 43.4 | ||||

| high | n | 39 | 33 | 36 | |||

| % | 21.7 | 37.9 | 21.7 | ||||

| Total | 180 | 87 | 166 | ||||

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||||

| Place of residence: Town | Level of satisfaction with life | low | n | 78 | 35 | 85 | 0.0003 |

| % | 32.8 | 20.5 | 33.7 | ||||

| average | n | 100 | 64 | 107 | |||

| % | 42.0 | 37.4 | 42.5 | ||||

| high | n | 60 | 72 | 60 | |||

| % | 25.2 | 42.1 | 23.8 | ||||

| Total | 238 | 171 | 252 | ||||

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||||

| Place of residence: Village | Level of satisfaction with life | low | n | 64 | 56 | 40 | 0.0016 |

| % | 36.4 | 23.9 | 28.6 | ||||

| average | n | 70 | 77 | 50 | |||

| % | 39.8 | 32.9 | 35.7 | ||||

| high | n | 42 | 101 | 50 | |||

| % | 23.9 | 43.2 | 35.7 | ||||

| Total | 176 | 234 | 140 | ||||

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||||

| Seniority: 1–5 years | Level of satisfaction with life | low | n | 9 | 16 | 8 | 0.0194 |

| % | 32.1 | 11.2 | 26.7 | ||||

| average | n | 10 | 48 | 10 | |||

| % | 35.7 | 33.6 | 33.3 | ||||

| high | n | 9 | 79 | 12 | |||

| % | 32.1 | 55.2 | 40.0 | ||||

| Total | 28 | 143 | 30 | ||||

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||||

| Seniority: 16–25 years | Level of satisfaction with life | low | n | 37 | 21 | 22 | 0.0463 |

| % | 41.6 | 43.8 | 28.9 | ||||

| average | n | 36 | 11 | 29 | |||

| % | 40.4 | 22.9 | 38.2 | ||||

| high | n | 16 | 16 | 25 | |||

| % | 18.0 | 33.3 | 32.9 | ||||

| total | n | 89 | 48 | 76 | |||

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||||

| Independent Variables | Place of Work | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHC | H | OSC | |||||

| Education: Bachelor’s degree | Level of satisfaction with life | low | n | 40 | 39 | 30 | 0.0003 |

| % | 35.7 | 20.6 | 30.6 | ||||

| average | n | 46 | 60 | 38 | |||

| % | 41.1 | 31.7 | 38.8 | ||||

| high | n | 26 | 90 | 30 | |||

| % | 23.2 | 47.6 | 30.6 | ||||

| Total | n | 112 | 189 | 98 | |||

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||||

| Education: Master’ degree | Level of satisfaction with life | low | n | 19 | 7 | 18 | 0.0176 |

| % | 27.5 | 9.5 | 20.9 | ||||

| average | n | 29 | 26 | 31 | |||

| % | 42.0 | 35.1 | 36.0 | ||||

| high | n | 21 | 41 | 37 | |||

| % | 30.4 | 55.4 | 43.0 | ||||

| Total | n | 69 | 74 | 86 | |||

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||||

| No additional qualification | Level of satisfaction with life | low | n | 119 | 68 | 105 | <0.0001 |

| % | 36.6 | 22.4 | 33.4 | ||||

| average | n | 128 | 103 | 136 | |||

| % | 39.4 | 34.0 | 43.3 | ||||

| high | n | 78 | 132 | 73 | |||

| % | 24.0 | 43.6 | 23.2 | ||||

| Total | n | 325 | 303 | 314 | |||

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||||

| Additional qualification | Level of satisfaction with life | low | n | 23 | 23 | 20 | 0.0470 |

| % | 25.8 | 22.5 | 25.6 | ||||

| average | n | 42 | 38 | 21 | |||

| % | 47.2 | 37.3 | 26.9 | ||||

| high | n | 24 | 41 | 37 | |||

| % | 27.0 | 40.2 | 47.4 | ||||

| Total | n | 89 | 102 | 78 | |||

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||||

| Position held: Not managerial | Level of satisfaction with life | low | n | 139 | 88 | 123 | <0.0001 |

| % | 34.8 | 23.1 | 32.6 | ||||

| average | n | 163 | 135 | 155 | |||

| % | 40.8 | 35.4 | 41.1 | ||||

| high | n | 98 | 158 | 99 | |||

| % | 24.5 | 41.5 | 26.3 | ||||

| Total | n | 400 | 381 | 377 | |||

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||||

| Independent Variables | Place of Work | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHC | H | OSC | |||||

| I don’t have a family | Level of satisfaction with life | low | n | 10 | 15 | 13 | 0.0219 |

| % | 27.0 | 18.5 | 32.5 | ||||

| average | n | 15 | 25 | 19 | |||

| % | 40.5 | 30.9 | 47.5 | ||||

| high | n | 12 | 41 | 8 | |||

| % | 32.4 | 50.6 | 20.0 | ||||

| Total | 37 | 81 | 40 | ||||

| 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||||

| I have a family | Level of satisfaction with life | low | n | 132 | 76 | 112 | <0.0001 |

| % | 35.0 | 23.5 | 31.8 | ||||

| average | n | 155 | 116 | 138 | |||

| % | 41.1 | 35.8 | 39.2 | ||||

| high | n | 90 | 132 | 102 | |||

| % | 23.9 | 40.7 | 29.0 | ||||

| Total | 377 | 324 | 352 | ||||

| 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||||

| Financial situation: Revenues equal to expenses | Level of satisfaction with life | low | n | 125 | 45 | 108 | <0.0001 |

| % | 35.2 | 19.8 | 33.2 | ||||

| average | n | 152 | 77 | 129 | |||

| % | 42.8 | 33.9 | 39.7 | ||||

| high | n | 78 | 105 | 88 | |||

| % | 22.0 | 46.3 | 27.1 | ||||

| Total | 355 | 227 | 325 | ||||

| 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||||

| Health self-assessment: Good | Level of satisfaction with life | low | n | 65 | 17 | 53 | 0.0026 |

| % | 31.0 | 17.0 | 28.2 | ||||

| average | n | 84 | 32 | 75 | |||

| % | 40.0 | 32.0 | 39.9 | ||||

| high | n | 61 | 51 | 60 | |||

| % | 29.0 | 51.0 | 31.9 | ||||

| Total | 210 | 100 | 188 | ||||

| 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||||

| Health self-assessment: Average | Level of satisfaction with life | low | n | 64 | 24 | 54 | 0.0008 |

| % | 40.5 | 28.2 | 38.3 | ||||

| average | n | 68 | 30 | 67 | |||

| % | 43.0 | 35.3 | 47.5 | ||||

| high | n | 26 | 31 | 20 | |||

| % | 16.5 | 36.5 | 14.2 | ||||

| Total | 158 | 85 | 141 | ||||

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bartosiewicz, A.; Nagórska, M. Place of Work and Level of Satisfaction with the Lives of Polish Nurses. Nurs. Rep. 2020, 10, 95-105. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep10020013

Bartosiewicz A, Nagórska M. Place of Work and Level of Satisfaction with the Lives of Polish Nurses. Nursing Reports. 2020; 10(2):95-105. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep10020013

Chicago/Turabian StyleBartosiewicz, Anna, and Małgorzata Nagórska. 2020. "Place of Work and Level of Satisfaction with the Lives of Polish Nurses" Nursing Reports 10, no. 2: 95-105. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep10020013

APA StyleBartosiewicz, A., & Nagórska, M. (2020). Place of Work and Level of Satisfaction with the Lives of Polish Nurses. Nursing Reports, 10(2), 95-105. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep10020013