Translation and Validation of the Portuguese Version of European School for Interdisciplinary Tinnitus Research Screening Questionnaire (ESIT-SQ-PT)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The ESIT-SQ

2.2. Translation and Back-Translation

2.3. Cross-Cultural Validation

2.4. Validation Study

3. Results

3.1. Translation and Back-Translation

3.2. Cross-Cultural Validation

3.3. Validation Study

3.3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.3.2. Tinnitus Characteristics

3.4. Psychometric Properties of the ESIT-SQ-PT

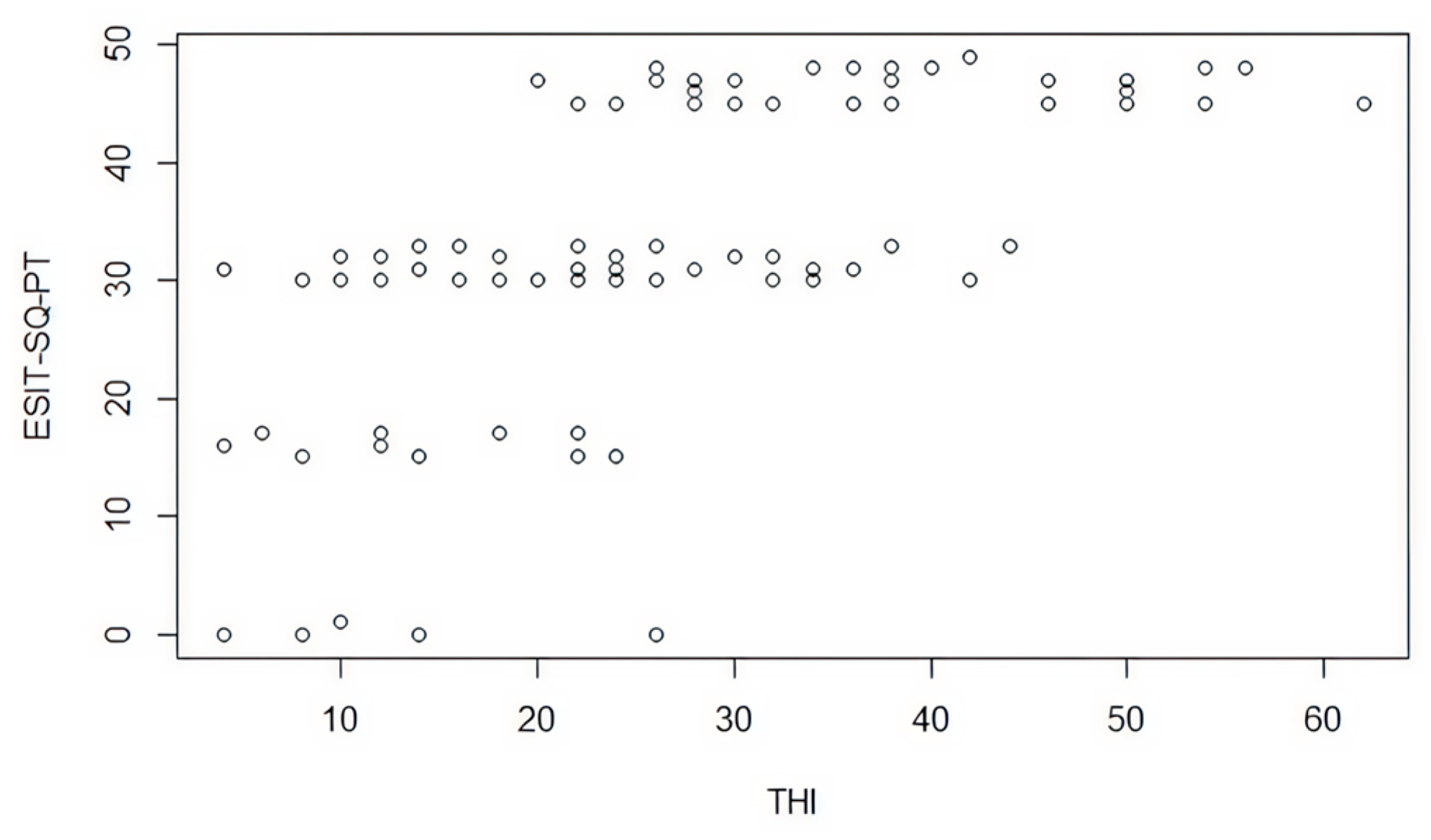

Validity

Reliability Study

3.5. Portuguese-Language Version of the ESIT-SQ

4. Discussion

- Part A

- Part O

- Part B

4.1. Validity of the ESIT-SQ-PT

4.2. Reliability of the ESIT-SQ-PT

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TIN | Tinnitus group |

| STIN | No tinnitus group |

| ESIT-SQ-PT | European School for Interdisciplinary Tinnitus Research Screening Questionnaire—Portuguese version |

References

- Dalrymple, S.N.; Lewis, S.H.; Philman, S. Tinnitus: Diagnosis and Management. Am. Fam. Physician 2021, 103, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haider, H.F.; Hoare, D.J.; Ribeiro, S.F.; Ribeiro, D.; Caria, H.; Trigueiros, N.; Borrego, L.M.; Szczepek, A.J.; Papoila, A.L.; Elarbed, A.; et al. Evidence for biological markers of tinnitus: A systematic review. Prog Brain Res. 2021, 262, 345–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A. Acufenos: Revisão Sistemática. 2017. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10451/30849 (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Chang, T.G.; Yao, Y.T.; Hsu, C.Y.; Yen, T.T. Exploring the interplay of depression, sleep quality, and hearing in tinnitus-related handicap: Insights from polysomnography and pure-tone audiometry. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarach, C.M.; Lugo, A.; Scala, M.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Cederroth, C.R.; Odone, A.; Garavello, W.; Schlee, W.; Langguth, B.; Gallus, S. Global prevalence and incidence of Tinnitus: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2022, 79, 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillard, R.; Decobecq, F.; Fraysse, M.J.; Favre, A.; Congedo, M.; Loche, V.; Boyer, M.; Londero, A. Validated French translation of the ESIT-SQ standardized tinnitus screening questionnaire. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2023, 140, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genitsaridi, E.; Partyka, M.; Gallus, S.; Lopez-Escamez, J.A.; Schecklmann, M.; Mielczarek, M.; Trpchevska, N.; Santacruz, J.L.; Schoisswohl, S.; Riha, C.; et al. Standardised profiling for tinnitus research: The European School for Interdisciplinary Tinnitus Research Screening Questionnaire (ESIT-SQ). Hear. Res. 2019, 377, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haro-Hernandez, E.; Perez-Carpena, P.; Unnikrishnan, V.; Spiliopoulou, M.; Lopez-Escamez, J.A. Standardized clinical profiling in Spanish patients with chronic tinnitus. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, D.A.; Zaragoza Domingo, S.; Hamdache, L.Z.; Manchaiah, V.; Thammaiah, S.; Evans, C.; Wong, L.; International Collegium of Rehabilitative Audiology and TINnitus Research NETwork. A good practice guide for translating and adapting hearing-related questionnaires for different languages and cultures. Int. J. Audiol. 2018, 57, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, V.; Meneses, R.F. Balanço da Utilização da Versão Portuguesa do Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) Y (THI). 2011. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.22/1922 (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- Han, B.I.; Lee, H.W.; Kim, T.Y.; Lim, J.S.; Shin, K.S. Tinnitus: Characteristics, causes, mechanisms, and treatments. J. Clin. Neurol. 2009, 5, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veile, A.; Zimmermann, H.; Lorenz, E.; Becher, H. Is smoking a risk factor for tinnitus? A systematic review, meta-analysis and estimation of the population attributable risk in Germany. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e016589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amanat, S.; Gallego-Martinez, A.; Lopez-Escamez, J.A. Genetic inheritance and its contribution to tinnitus. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 51, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miura, M.; Goto, F.; Inagaki, Y.; Nomura, Y.; Oshima, T.; Sugaya, N. The effect of comorbidity between tinnitus and dizziness on perceived handicap, psychological distress, and quality of life. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, T.G.; Pedalini, M.E.B.; Bento, R.F. Hiperacusia: Artigo de revisão. Arq. Int. Otorrinolaringol. 1999, 3, 184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Hallam, R.S. Correlates of sleep disturbance in chronic distressing tinnitus. Scand. Audiol. 2009, 25, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babson, K.A.; Trainor, C.D.; Feldner, M.T.; Blumenthal, H. A test of the effects of acute sleep deprivation on general and specific self-reported anxiety and depressive symptoms: An experimental extension. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2010, 41, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ümüş Özbey-Yücel Uçar, A.; Aydoğan, Z.; Tokgoz-Yilmaz, S.; Beton, S. The effects of dietary and physical activity interventions on tinnitus symptoms: An RCT. Auris Nasus Larynx 2022, 50, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, L.N.; Sanchez, T.G. Zumbido e telefones celulares: O papel da radiação de radiofrequência eletromagnética. Rev. Bras. Otorrinolaringol. 2016, 82, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Chaput, J.P.; Dutil, C.; Sampasa-Kanyinga, H. Sleeping hours: What is the ideal number and how does age impact this? Nat. Sci. Sleep 2018, 10, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisz, N.; Moratti, S.; Meinzer, M.; Dohrmann, K.; Elbert, T. Tinnitus perception and distress is related to abnormal spontaneous brain activity as measured by magnetoencephalography. PLoS Med. 2005, 2, e153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, V.; Cooke, B.; Eitutis, S.; Simpson, M.T.W.; Beyea, J.A. Approach to tinnitus management. Can. Fam. Physician 2018, 64, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | %(n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Tinnitus daily or almost every day | 86.1% (105) | |

| Heard their tinnitus constantly or almost always | 80.5% (99) | |

| Having intermittent tinnitus | 19.5% (24) | |

| Having tinnitus for years | 54.1% (66) | |

| Moderate level of concern regarding tinnitus | 41.7% (55) | |

| Feeling bothered for some time | 47.9% (58) | |

| Tinnitus as a single sound | 70.5% (93) | |

| Tinnitus began suddenly | 50% (66) | |

| Not knowing when tinnitus began | 26% (34) | |

| Initial onset of tinnitus related with stress | 18.9% (27) | |

| Initial onset of tinnitus related to another event | 21% (30) | |

| Taking medication at the time of tinnitus onset | 31.0% (39) | |

| No direct relationship between the disease and the onset of tinnitus | 71% (93) | |

| Tinnitus loudness variable | 54.2% (71) | |

| Tinnitus as a tone | 37.5% (51) | |

| High pitched tinnitus | 43.3% (55) | |

| Bilateral tinnitus | 23.3% (31) | |

| Tinnitus not rhythmic | 96.6% (98) | |

| Tinnitus audible by another person | 24.6% (32) | |

| Reduction in tinnitus | Optimal quality of sleep | 13.2% (26) |

| Being relaxed | 11.2% (22) | |

| Loud sounds | 18.8% (37) | |

| Nothing | 17.8% (35) | |

| Increasing in tinnitus | Silent environment | 31.1% (70) |

| Being stressed or anxious | 18.7% (42) | |

| Min. 1 | 1st Qu. 2 | Median | Mean | 3rd Qu. 3 | Max 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1-O6 | STIN | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| A1-O6 | TIN | 0 | 0 | 0.82 | 0.54 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| O7-A17 | STIN | 0.91 | 1 | 1 | 0.99 | 1 | 1 |

| O7-A17 | TIN | 0 | 0.03 | 0.83 | 0.56 | 0.91 | 1 |

| Min. 1 | 1st Qu. 2 | Median | Mean | 3rd Qu. 3 | Max 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1-B22.1 | TIN | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.63 | 0.49 | 0.83 | 0.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Haider, H.F.; Fernandes, A.S.; Aguiar, A.F.; Oliveira, B.; Peixoto, I.; Antunes, M.; Hoare, D.J.; Caria, H. Translation and Validation of the Portuguese Version of European School for Interdisciplinary Tinnitus Research Screening Questionnaire (ESIT-SQ-PT). Audiol. Res. 2026, 16, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres16010002

Haider HF, Fernandes AS, Aguiar AF, Oliveira B, Peixoto I, Antunes M, Hoare DJ, Caria H. Translation and Validation of the Portuguese Version of European School for Interdisciplinary Tinnitus Research Screening Questionnaire (ESIT-SQ-PT). Audiology Research. 2026; 16(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres16010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaider, Haúla F., Ana Solange Fernandes, Ana Filipa Aguiar, Beatriz Oliveira, Iris Peixoto, Marília Antunes, Derek James Hoare, and Helena Caria. 2026. "Translation and Validation of the Portuguese Version of European School for Interdisciplinary Tinnitus Research Screening Questionnaire (ESIT-SQ-PT)" Audiology Research 16, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres16010002

APA StyleHaider, H. F., Fernandes, A. S., Aguiar, A. F., Oliveira, B., Peixoto, I., Antunes, M., Hoare, D. J., & Caria, H. (2026). Translation and Validation of the Portuguese Version of European School for Interdisciplinary Tinnitus Research Screening Questionnaire (ESIT-SQ-PT). Audiology Research, 16(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres16010002