Abstract

Background: Spinal Muscular Atrophy type 1 (SMA type 1) is a genetic neuromuscular disease that typically presents before 6 months of age and is characterized by profound hypotonia, progressive muscle weakness, and early involvement of respiratory and bulbar musculature. Swallowing impairment (dysphagia) is a hallmark of SMA type 1 and significantly contributes to morbidity. Despite the documented benefits of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) in terms of enhanced survival and motor outcomes, their impact on swallowing remains understudied. Aim: This study aims to longitudinally characterize swallowing function in children with SMA type 1 treated with DMTs, while contextualizing these findings in relation to the patients’ current motor abilities and cognitive performance. Materials and Methods: A single-center, longitudinal, observational study was conducted at IRCCS Besta, Milan, Italy, from 2021 to 2025. Swallowing function was evaluated using four validated scales (MAS, OrSAT, FILS, and p-FOIS), while motor and cognitive functions were assessed using CHOP-INTEND and age-appropriate cognitive tests (DQ/IQ). Patients were stratified by baseline swallowing status, pharmacological therapy, and age at DMT administration. Non-parametric statistical tests were applied. Results: No statistically significant changes in swallowing function were observed over one year in the overall cohort or its subgroups, despite significant improvements in motor function. MAS/e, FILS, and p-FOIS showed moderate associations with CHOP-INTEND and DQ/IQ scores. Conclusions: Swallowing function in children with SMA type 1 remained largely stable, while motor function significantly improved over one year, regardless of baseline swallowing status, DMT type, and age at administration. These findings underscore the need for standardized, longitudinal assessments of swallowing, motor, and cognitive functions in the management of SMA type 1.

1. Introduction

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a genetic neuromuscular disease characterized by the progressive degeneration of spinal and bulbar motor neurons. The primary genetic etiology of SMA is a homozygous deletion of the SMN1 gene, leading to deficient production of the survival motor neuron (SMN) protein, which is essential for motor neuron survival and function [1,2].

Werdnig-Hoffmann disease, also known as spinal muscular atrophy type 1 (SMA type 1), is the most prevalent and severe form of SMA, with symptoms onset occurring before 6 months of age [3]. It is characterized by profound hypotonia, progressive muscle weakness, and early involvement of respiratory and bulbar muscles [4]. Prior to the availability of disease-modifying treatments (DMTs), SMA type 1 was associated with significant morbidity and early mortality, typically within the first two years of life.

Bulbar dysfunction, particularly swallowing impairment (dysphagia), is a defining feature of SMA type 1, typically manifesting within the first 12 months of life [1,5,6,7,8]. Dysphagia carries a significant risk of malnutrition, aspiration pneumonia, and failure to thrive [9,10,11]. Therefore, early and comprehensive assessment of swallowing function is essential for the timely implementation of nutritional and respiratory support interventions.

The advent of DMTs—including nusinersen (an antisense oligonucleotide), onasemnogene abeparvovec (a gene replacement therapy), and risdiplam (a small molecule splicing modifier of SMN2)—has fundamentally transformed the clinical trajectory of SMA type 1 by enabling prolonged survival and improved motor function outcomes [12]. However, the therapeutic impact on bulbar function, particularly swallowing ability, remains incompletely characterized. While preliminary reports suggest stabilization or modest improvements in oral feeding abilities [13,14], other studies document persistent or progressive dysphagia [9,15], underscoring the critical need for systematic longitudinal evaluation.

Despite the well-established importance of dysphagia management in SMA type 1, standardized protocols for serial swallowing assessments remain lacking. Current practice shows considerable variability in assessment frequency, evaluation methods, and clinical triggers for reassessment, which may lead to delayed therapeutic interventions and suboptimal patient outcomes.

This study aims to characterize the longitudinal evolution of swallowing function in children with SMA type 1, while contextualizing these findings within the patients’ current motor abilities and cognitive performance. Our first hypothesis is that DMTs have a significant impact on swallowing function, as measured by standardized and specific evaluation scales. Furthermore, we hypothesize that the interplay between functional domains may be relevant in the recovery of feeding abilities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This is a single-center, longitudinal, observational study aiming to examine swallowing function in pharmacologically treated SMA type 1 patients. Assessments were conducted between September 2021 and June 2025 at the SFERA (Swallowing and Feeding Rehabilitation and Assessment) outpatient clinic of the Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milan, Italy.

All assessments were conducted as part of routine clinical practice for patients with SMA type 1 at our center. Motor and cognitive evaluations were included if they were performed during the same follow-up visit as the swallowing assessment, or within a short temporal proximity to it.

2.2. Data Collection and Ethical Considerations

Demographic characteristics, clinical data, DMTs information, and motor milestone development were systematically collected during routine assessments and recorded in an anonymized database. All procedures adhered to Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the 1964 Helsinki Declaration, and its subsequent amendments [16]. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta (CET 27/25).

2.3. Patient Inclusion and Stratification

All SMA type 1 patients who were regularly followed up at our clinic were screened for participation in the study. To be classified as SMA type 1, patients had to present with motor symptom onset before 6 months of age and have a confirmed molecular diagnosis of SMA [3].

Children were eligible if they had undergone at least two swallowing assessments, with a minimum interval of 12 months between them. We established a threshold of 9 months for the first swallowing assessment to enable oral feeding across all consistencies [17]; only evaluations performed after the initiation of MDTs were included.

All other SMA types, as well as patients with only a single swallowing assessment, were excluded from the study.

Based on age at symptom onset, children were classified into three groups [18]: SMA type 1a (before one month), SMA type 1b (between one and three months), and SMA type 1c (between three and six months). We further distinguished patients into “early-treated” and “late-treated” groups, defined by the conventional threshold of 6 months between symptom onset and initiation of DMTs. Finally, children were classified based on their pre-treatment swallowing status (normal versus impaired) and sitting ability (sitters versus non-sitters).

2.4. Swallowing Assessment Protocol

Swallowing assessments were conducted using four validated swallowing scales: Mealtime Assessment Scale (MAS) [19,20], Oral and Swallowing Abilities Tool (OrSAT) [21], Food Intake LEVEL Scale (FILS) [22], and Paediatric Functional Oral Intake Scale (p-FOIS) [15].

MAS assesses the safety and efficacy of swallowing during a meal and includes four subscales addressing structural, functional, and environmental factors influencing the meal, as well as swallowing safety and efficacy. The safety score ranges from 0 to 12, and the efficacy score from 0 to 18, with higher scores (or percentages) indicating less safe or less effective swallowing [20].

OrSAT is a simple, validated tool for assessing oral motor function and swallowing in infants with SMA type 1. It consists of a checklist of abilities, with the maximum score varying according to the patient’s age. Functional impairment is categorized into four levels, ranging from no impairment to severe disorder. The tool was originally validated in children aged 0–2 years, but its use has been extended to include children up to 4 years [9]. To facilitate age-independent comparisons, OrSAT scores were expressed as a percentage of the maximum age-appropriate score, an approach not previously reported in the literature.

FILS is a 10-point observer-rated scale that measures the severity of dysphagia [22]. Scores of 1–3 indicate no oral intake, while scores above 4 reflect partial or total oral intake.

p-FOIS is a 6-point scale assessing changes in functional eating abilities [15]. Scoring is based on clinical observation and the patient’s habitual eating patterns. Scores 2–6 correspond to increasing levels of partial or total oral intake, whereas score 1 indicates no oral intake.

In line with standard clinical practice, all mealtime sessions were videotaped to ensure accurate scoring.

2.5. Motor and Cognitive Assessment

Motor function was evaluated using the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders (CHOP-INTEND) scale [23] during the routine multidisciplinary evaluations. The CHOP-INTEND was developed and validated for children up to 2 years of age; however, consistent with common practice in this population, it was also administered to older patients. Children were classified as “sitters” based on Item 26 of the Bayley-III gross motor scale [24], which assesses the ability to maintain an independent sitting position for 30 seconds.

Cognitive and developmental assessments are a routine part of clinical practice for SMA type 1 patients at our Center. They were evaluated using the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition (Bayley-III) [24], the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, Fourth Edition (WPPSI-IV) [25], or the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) [26], according to the patients’ age. We included a single cognitive assessment for each patient, performed as close as possible to the first swallowing assessment (T0).

For both motor and cognitive function assessments, only the total score of the respective scale was considered.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Being an exploratory pilot study, we included in the analysis all patients followed at our institute who met the eligibility criteria. No power analysis was performed to define the sample size.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (version 28.0, IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Scale data that were not normally distributed are expressed as the median (range/interquartile range [IQR]). Nominal and categorical variables are presented as frequency (percentage [%]). Due to either the non-normal distribution or the ordinal nature of the variables, data were analyzed using non-parametric tests. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to evaluate changes in swallowing function scores from baseline (T0) to the one-year follow-up (T1) for the same subjects, both for the entire sample and for different subgroups. To evaluate differences in the magnitude of change (T1-T0) between subgroups, the Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis test were applied. Due to the presence of a high number of tied ranks and an unbalanced sample size between subgroups, the exact two-tailed significance value was reported, as it provides a more accurate estimate of statistical significance under these conditions. Spearman’s rank correlation was used for all associations; the magnitude of correlation coefficients was interpreted according to Schober, Boer, and Schwarte’s classification [27]. For all statistical analyses significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

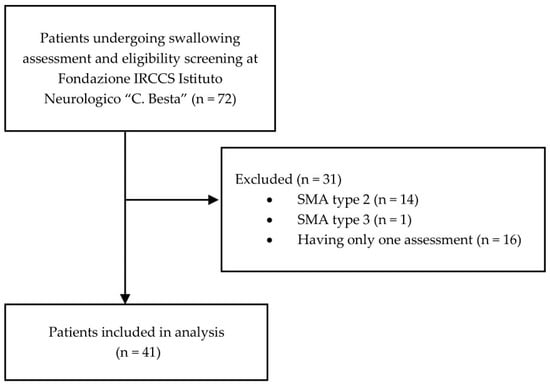

This longitudinal study evaluated swallowing function in 41 children with SMA type 1 who met the inclusion criteria: a confirmed diagnosis of SMA type 1 and at least two swallowing assessments spaced by at least 12 months.

Fifteen patients were excluded because they had a different SMA type, and 16 SMA type 1 patients were excluded because of the absence of a follow-up assessment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patients eligibility flowchart.

Among the included patients, 38 (92.7%) carried two SMN2 copies, while 3 children (7.3%) had three SMN2 copies.

Patients received nusinersen (16/41, 39%), risdiplam (8/41, 19.5%), or onasemnogene abeparvovec (17/41, 41.5%) as their initial treatment.

Comprehensive demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population.

The results of longitudinal swallowing assessments (MAS, OrSAT, FILS, FOIS) and CHOP-INTEND scores are presented in Table 2. Follow-up OrSAT data were available for only 18 patients, as the remaining children were older than four years at T0 or T1. A second CHOP-INTEND assessment (T1) was not available for one patient; therefore, only 40 children were included in this analysis.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for MAS, OrSAT, FILS, p-FOIS, and CHOP-INTEND at first (T0) and second (T1) swallowing assessment.

A developmental/cognitive assessment was performed in 31/41 children (75.6%) at T0, at a median age of 32.9 months (range: 18.0–118.8). The median score—Developmental Quotient (DQ) or Intelligence Quotient (IQ)—was 85 (IQR: 29; range: 55–120).

No statistically significant differences were observed within the entire group between baseline (T0) and one-year follow-up (T1) assessments for any of the swallowing scales. In contrast, motor function, as measured by the CHOP-INTEND, showed a significant improvement (p < 0.001) (see Table A1 in Appendix A). Similarly, no significant differences in any of the swallowing scales were found between T0 and T1 when patients were stratified by treatment timing or type (Table A2 and Table A3 in Appendix A). OrSAT scores could not be calculated for late-treated patients due to age-related limitations. On the other hand, a significant improvement in motor function was observed in the early-treated group.

No statistically significant changes were observed in any of the swallowing-specific scales—OrSAT, MAS/e, MAS/s, FILS, or p-FOIS—after one year of follow-up, regardless of pre-treatment swallowing status, whether patients had adequate or impaired baseline function (Table A4, Appendix A). Conversely, CHOP-INTEND scores increased significantly over the same period in both groups.

Finally, no statistically significant changes in swallowing abilities were detected either in patients unable to maintain a sitting position or in sitters, whereas CHOP-INTEND scores significantly improved between T0 and T1 among sitters (Table A5 in Appendix A).

CHOP-INTEND scores were significantly correlated with swallow efficacy (MAS/e) and swallowing observer-rating scales (p-FOIS and FILS) at both T0 and T1, whereas no association was found with OrSAT and MAS/s (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between swallowing scales and CHOP-INTEND scores at T0 and T1.

Furthermore, a moderate association was observed between developmental/cognitive function (DQ/IQ) and motor function, as well as between cognitive function and swallow efficacy (MAS/e), and between cognitive function and p-FOIS (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association between swallowing/motor function and cognitive development at T0.

No association was found between patients’ age and changes in swallowing scale scores from T0 to T1 (Table A6 in the Appendix A).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal observational study to quantitatively assess the development of swallowing function in children with SMA type 1, using a standardized mealtime assessment performed by speech therapists (MAS), in addition to other clinical tools validated in SMA (OrSAT, p-FOIS). The use of clinical assessments is valuable, providing a simple, non-invasive, universally applicable, and easily replicable method for follow-up. This approach reduces reliance on instrumental assessments, which can be reserved for patients exhibiting overt signs of dysphagia during mealtime evaluation or presenting with complex clinical profiles that may limit the sensitivity of clinical assessment.

The study findings indicate overall stability in swallowing function after at least 12 months of follow-up, with no significant improvement or deterioration detected, regardless of pre-treatment swallowing status, sitting ability, treatment timing, or DMT administered. These results are consistent with previous qualitative studies [9,10,13,15,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] which demonstrated the positive impact of DMTs on dysphagia, and reinforce the evidence for the efficacy of DMTs in mitigating or preventing the deterioration of swallowing, which typically occurs early in the natural history of SMA type 1. However, heterogeneity in outcome measures limits direct comparisons across studies, with some reporting only the initiation of enteral nutrition as a marker of swallowing decline [10,30,31,33,34,35], while others include clinical and/or instrumental assessments [9,13,15,28,29,37,38,39,40,41,42,43].

In contrast to the natural history of SMA type 1—wherein children typically lose oral feeding ability within the first year of life, with the nature and frequency of deficits varying according to phenotype severity [9,11,21,44,45,46,47,48]—treated children appear to maintain their baseline swallowing function throughout the follow-up period, regardless of the age at assessment.

We consider these findings fairly representative of the broader SMA type 1 population, as, in line with previous research, we observed significant improvements in motor function [5,12,28,37,49], particularly in “early-treated” children. This observation supports the growing consensus that early intervention is crucial for maximizing motor outcomes in SMA type 1 [35].

Moreover, these data suggest that while DMTs can positively impact motor function, their effect on swallowing appears primarily to stabilize the pre-treatment status—preventing deterioration—rather than induce improvement. This dissociation may reflect distinct pathophysiological mechanisms affecting motor versus bulbar muscles, differences in the tissue distribution and efficacy of pharmacological treatments, or variability in the sensitivity of assessment tools and rehabilitation protocols. In fact, all children in this cohort received regular physiotherapy, whereas only two of them underwent targeted swallowing interventions (Table 2). This imbalance in rehabilitative focus may contribute to the observed divergence in functional outcomes. While the role of motor rehabilitation is well recognized and routinely integrated into standard care, the impact of swallowing rehabilitation remains underexplored in this population. Further studies are warranted to evaluate whether systematic, individualized dysphagia interventions could enhance swallowing function, particularly in the context of early pharmacological treatment.

A significant association was found between swallowing efficacy (MAS/e, pFOIS) and motor function, but this was not observed for swallowing safety (MAS/s) and OrSAT, likely reflecting the involvement of different pathophysiological mechanisms affecting distinct aspects of swallowing.

Moderate associations between cognitive function and both motor and swallowing efficacy scores suggest that developmental/cognitive status may influence or reflect overall neuromuscular function and disease severity in SMA type 1. The impact of SMA type 1 on cognitive function remains debated. While we are fully aware of the complexity involved in assessing cognition in children with motor disabilities, cognitive function may play a role in the development of compensatory strategies, not only in the motor domain but also in swallowing. The interrelationships among these domains warrant further investigation, as cognitive development may be influenced by disease burden, nutritional status, or the effects pharmacological therapy.

Finally, additional research is needed to examine in depth the evolution of cognitive, motor, and swallowing functions in children identified through newborn screening. Early identification enables the initiation of treatment during a critical developmental window, potentially altering the natural history of the disease. However, the long-term impact of early treatment on the interplay between cognitive, motor, and bulbar functions remains poorly understood. A better understanding of these trajectories could inform future clinical practice and care planning, guiding the design of interdisciplinary interventions aimed at optimizing developmental outcomes.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size in subgroup analyses and the heterogeneity in patients’ ages at the time of the swallowing assessments. Swallowing abilities develop physiologically during early childhood, with toddlers typically able to manage adult-like solid foods between two and three years of life [17]. In our sample, 29% of children were under 2 years of age at the first assessment; therefore, their ability to handle all food consistencies may have evolved over the course of the follow-up. Future studies should more precisely investigate the development of swallowing abilities stratifying patients according to age, in order to achieve greater stability and generalizability of the findings. Moreover, the median follow-up duration was 12 months, which may be too short to fully capture meaningful changes in motor and swallowing functions. Longer follow-up studies are warranted to better characterize the progression of cognitive, swallowing, and motor abilities in this population.

In addition, this study relied exclusively on clinical scales to evaluate swallowing function but did not include objective instrumental assessments. While clinical scales are non-invasive, provide valuable information in daily practice and enable standardized comparisons across patients, they cannot fully capture the physiological mechanisms underlying swallowing impairment. Future studies integrating both clinical and instrumental tools could therefore offer a more comprehensive understanding of swallowing function and its evolution in this population.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that while motor function significantly improves with early treatment, swallowing function remains stable for at least a one-year period, regardless of the DMT administered. These findings highlight the need for comprehensive management strategies that target both motor and bulbar functions to optimize patient outcomes. Early intervention remains essential for motor improvement and the preservation of swallowing abilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G. and R.M.; methodology, S.G. and R.M.; validation, S.G. and R.M.; formal analysis, S.G.; investigation, S.G.; resources, S.G., C.D., S.P., M.T.A., R.Z., S.B., L.R. and R.M.; data curation, S.G., C.D., S.P., M.T.A., R.Z., S.B., L.R. and R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G.; writing—review and editing, S.G., C.D., S.P., M.T.A., R.Z., S.B., L.R. and R.M.; visualization, S.G.; supervision, R.M.; project administration, R.M.; funding acquisition, R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (RRC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Foundation IRCCS Carlo Besta Neurological Institute (CET 27/25, on 19 March 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the work of the SFERA working group components: Simona Bertoli, Ramona De Amicis, Alessandro Campari, Antonio Schindler, Maria Rosa Scopelliti, Anna Mandelli. In addition, we acknowledge the work of the Developmental Neurology Unit at Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta: Emanuela Pagliano, Ilaria Pedrinelli, Maria Foscan, Marta Viganò, Alessia Marchi, Sara Mazzanti, and Tiziana Casalino. The authors gratefully acknowledge Rosalind Hendricks for her assistance with the English language revision. The authors acknowledge the partial support for the clinical activities of the SFERA working group provided by Roche Italia (2023–2024).

Conflicts of Interest

R.M. and C.D. received consultancy fees and speaker honoraria from Roche, Novartis, and Biogen. RZ received consultancy fees and speaker honoraria from Roche and Biogen. S.G., S.P., M.T.A., S.B. and L.R. have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CHOP-INTEND | Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders |

| DQ | Developmental Quotient |

| FILS | Food Intake LEVEL Scale |

| IQ | Intelligence Quotient |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| MAS | Mealtime Assessment Scale |

| OrSAT | Oral and Swallowing Abilities Tool |

| p-FOIS | Paediatric Functional Oral Intake Scale |

| SFERA | Swallowing and Feeding Rehabilitation and Assessment |

| SMA | Spinal Muscular Atrophy |

| SMA type 1 | Spinal Muscular Atrophy type 1 |

| SMN | Survival Motor Neuron |

| T0 | Baseline |

| T1 | One-year follow-up |

| WISC-IV | Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition |

| WPPSI-IV | Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, Fourth Edition |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Comparison of swallowing function scores between baseline (T0) and one-year follow-up (T1) in the whole population.

Table A1.

Comparison of swallowing function scores between baseline (T0) and one-year follow-up (T1) in the whole population.

| Test | n | Negative Ranks | Positive Ranks | Ties | Z | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OrSAT | 18 | 5 | 6 | 7 | −0.224 | 0.823 |

| MAS | ||||||

| MAS/s | 41 | 11 | 13 | 17 | −1.011 | 0.312 |

| MAS/e | 41 | 10 | 20 | 11 | −1.059 | 0.290 |

| FILS | 41 | 6 | 8 | 27 | −0.289 | 0.772 |

| p-FOIS | 41 | 4 | 7 | 30 | −0.189 | 0.850 |

| CHOP-INTEND | 40 | 5 | 22 | 13 | −3.503 | <0.001 ** |

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to evaluate changes in swallowing function scores from baseline (T0) to the one-year follow-up (T1) within the same subjects. **: statistically significant result with p < 0.01.

Table A2.

Comparison of swallowing function scores between baseline (T0) and one-year follow-up (T1) according to treatment timing.

Table A2.

Comparison of swallowing function scores between baseline (T0) and one-year follow-up (T1) according to treatment timing.

| Test | Treatment Group | n | Negative Ranks | Positive Ranks | Ties | Z | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OrSAT | Early | 18 | 5 | 6 | 7 | −0.224 | 0.823 |

| MAS | |||||||

| MAS/s | Early | 37 | 9 | 12 | 16 | −1.169 | 0.242 |

| Late | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | −0.577 | 0.564 | |

| MAS/e | Early | 37 | 8 | 19 | 10 | −1.152 | 0.249 |

| Late | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| FILS | Early | 37 | 6 | 7 | 24 | −0.464 | 0.643 |

| Late | 4 | 0 | 1 | 3 | −1.000 | 0.317 | |

| p-FOIS | Early | 37 | 4 | 5 | 28 | −0.312 | 0.755 |

| Late | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | −1.414 | 0.157 | |

| CHOP-INTEND | Early | 37 | 4 | 20 | 13 | −3.636 | <0.001 ** |

| Late | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to evaluate changes in swallowing function scores from baseline (T0) to the one-year follow-up (T1) within the same subjects, stratified according to treatment timing. **: statistically significant result with p < 0.01.

Table A3.

Comparison of swallowing and motor function scores between baseline (T0) and one-year follow-up (T1) according to DMT.

Table A3.

Comparison of swallowing and motor function scores between baseline (T0) and one-year follow-up (T1) according to DMT.

| Test | Treatment | n | Negative Ranks | Positive Ranks | Ties | Z | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OrSAT | N | 7 | 3 | 2 | 2 | −0.813 | 0.416 |

| O | 11 | 2 | 4 | 5 | −1.160 | 0.246 | |

| MAS | |||||||

| MAS/s | R | 8 | 5 | 1 | 2 | −1.000 | 0.317 |

| N | 16 | 4 | 6 | 6 | −0.417 | 0.638 | |

| O | 17 | 2 | 6 | 9 | −1.496 | 0.135 | |

| MAS/e | R | 8 | 2 | 2 | 4 | −0.730 | 0.465 |

| N | 16 | 4 | 9 | 3 | −0.950 | 0.342 | |

| O | 17 | 4 | 9 | 4 | −1.077 | 0.282 | |

| FILS | R | 8 | 0 | 2 | 6 | −1.342 | 0.180 |

| N | 16 | 3 | 3 | 10 | −0.333 | 0.739 | |

| O | 17 | 3 | 3 | 11 | −0.744 | 0.457 | |

| p-FOIS | R | 8 | 0 | 1 | 7 | −1.000 | 0.317 |

| N | 16 | 1 | 4 | 11 | −0.707 | 0.480 | |

| O | 17 | 3 | 2 | 12 | −0.707 | 0.480 | |

| CHOP-INTEND | R | 8 | 1 | 4 | 3 | −1.625 | 0.104 |

| N | 15 | 3 | 8 | 4 | −1.568 | 0.117 | |

| O | 17 | 1 | 10 | 6 | −2.803 | 0.005 ** |

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to evaluate changes in swallowing function scores from baseline (T0) to the one-year follow-up (T1) within the same subjects, stratified according to DMTs. **: statistically significant result with p < 0.01.

Table A4.

Comparison of swallowing function scores between baseline (T0) and one-year follow-up (T1) according to pre-therapy swallowing status.

Table A4.

Comparison of swallowing function scores between baseline (T0) and one-year follow-up (T1) according to pre-therapy swallowing status.

| Test | Pre-Therapy Swallowing Status | n | Negative Ranks | Positive Ranks | Ties | Z | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OrSAT | Normal | 13 | 4 | 3 | 6 | −0.171 | 0.865 |

| Impaired | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | −0.365 | 0.715 | |

| MAS | |||||||

| MAS/s | Normal | 27 | 7 | 5 | 15 | −0.120 | 0.905 |

| Impaired | 14 | 4 | 8 | 2 | −1.339 | 0.181 | |

| MAS/e | Normal | 27 | 5 | 13 | 9 | −0.952 | 0.341 |

| Impaired | 14 | 5 | 7 | 2 | −0.629 | 0.529 | |

| FILS | Normal | 27 | 4 | 7 | 16 | −0.552 | 0.581 |

| Impaired | 14 | 2 | 1 | 11 | −1.069 | 0.285 | |

| p-FOIS | Normal | 27 | 2 | 5 | 20 | −1.134 | 0.257 |

| Impaired | 14 | 2 | 2 | 10 | −0.736 | 0.461 | |

| CHOP-INTEND | Normal | 27 | 2 | 14 | 11 | −2.775 | 0.006 ** |

| Impaired | 13 | 3 | 8 | 2 | −2.050 | 0.040 * |

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to evaluate changes in swallowing function scores from baseline (T0) to the one-year follow-up (T1) within the same subjects, stratified according to pre-DMT swallowing status. *: statistically significant with p < 0.05; **: statistically significant result with p < 0.01.

Table A5.

Comparison of swallowing function scores between baseline (T0) and one-year follow-up (T1) according to sitting position.

Table A5.

Comparison of swallowing function scores between baseline (T0) and one-year follow-up (T1) according to sitting position.

| Test | Sitting Position | n | Negative Ranks | Positive Ranks | Ties | Z | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OrSAT | Yes | 16 | 4 | 6 | 6 | −0.719 | 0.472 |

| No | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | −1.000 | 0.317 | |

| MAS | |||||||

| MAS/s | Yes | 33 | 10 | 8 | 15 | −0.178 | 0.859 |

| No | 8 | 1 | 5 | 2 | −1.725 | 0.084 | |

| MAS/e | Yes | 33 | 8 | 16 | 9 | −0.390 | 0.697 |

| No | 8 | 2 | 4 | 2 | −1.581 | 0.114 | |

| FILS | Yes | 33 | 5 | 8 | 20 | −0.180 | 0.857 |

| No | 8 | 1 | 0 | 7 | −1.000 | 0.317 | |

| p-FOIS | Yes | 33 | 3 | 5 | 25 | −0.302 | 0.763 |

| No | 8 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| CHOP-INTEND | Yes | 33 | 3 | 18 | 12 | −3.414 | <0.001 ** |

| No | 7 | 2 | 4 | 1 | −1.051 | 0.293 |

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to evaluate changes in swallowing function scores from baseline (T0) to the one-year follow-up (T1) within the same subjects, stratified according to their ability to maintain sitting position. **: statistically significant result with p < 0.01.

Table A6.

Association between age at assessment and changes in swallowing scale scores at T0 and T1.

Table A6.

Association between age at assessment and changes in swallowing scale scores at T0 and T1.

| Swallowing Scale | rs | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| OrSAT | −0.329 | 0.183 |

| MAS/s | −0.244 | 0.159 |

| MAS/e | −0.147 | 0.359 |

| FILS | −0.035 | 0.829 |

| p-FOIS | −0.039 | 0.808 |

Spearman’s rank correlation was used to assess the strength and direction of the monotonic association between the difference in swallowing scales scores at T0 and T1 and age at assessment. The magnitude of the correlation coefficients was interpreted according to the classification proposed by Schober, Boer, and Schwarte [27].

References

- Kolb, S.J.; Coffey, C.S.; Yankey, J.W.; Krosschell, K.; Arnold, W.D.; Rutkove, S.B.; Swoboda, K.J.; Reyna, S.P.; Sakonju, A.; Darras, B.T.; et al. Natural history of infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 82, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, S.; Bürglen, L.; Reboullet, S.; Clermont, O.; Burlet, P.; Viollet, L.; Benichou, B.; Cruaud, C.; Millasseau, P.; Zeviani, M.; et al. Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell 1995, 80, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butchbach, M.E. Copy Number Variations in the Survival Motor Neuron Genes: Implications for Spinal Muscular Atrophy and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2016, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, S.J.; Kissel, J.T. Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Neurol. Clin. 2015, 33, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, R.S.; Mercuri, E.; Darras, B.T.; Connolly, A.M.; Kuntz, N.L.; Kirschner, J.; Chiriboga, C.A.; Saito, K.; Servais, L.; Tizzano, E.; et al. Nusinersen versus sham control in infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrattan, K.E.; Graham, R.J.; Didonato, C.J.; Darras, B.T. Dysphagia phenotypes in spinal muscular atrophy: The past, present, and promise for the future. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2021, 30, 1008–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, J.; Witt, S.; Johannsen, J.; Weiss, D.; Denecke, J.; Dumitrascu, C.; Nießen, A.; Quitmann, J.H.; Pflug, C.; Flügel, T. DySMA—An Instrument to Monitor Swallowing Function in Children with Spinal Muscular Atrophy ages 0 to 24 Months: Development, Consensus, and Pilot Testing. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2024, 11, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnkrant, D.J.; Pope, J.F.; Martin, J.E.; Repucci, A.H.; Eiben, R.M. Treatment of type I spinal muscular atrophy with noninvasive ventilation and gastrostomy feeding. Pediatr. Neurol. 1998, 18, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Heul, A.M.B.; Cuppen, I.; Wadman, R.I.; Asselman, F.; Schoenmakers, M.A.G.C.; Van De Woude, D.R.; Gerrits, E.; Van Der Pol, W.L.; Van Den Engel-Hoek, L. Feeding and Swallowing Problems in Infants with Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type 1: An Observational Study. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2020, 7, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, G.R.; Gushue, C.; Kotha, K.; Shell, R. The respiratory impact of novel therapies for spinal muscular atrophy. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2021, 56, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.A.; Suh, D.I.; Chae, J.H.; Shin, H.I. Trajectory of change in the swallowing status in spinal muscular atrophy type I. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020, 130, 109818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, S.; Waldrop, M.A.; Connolly, A.M.; Mendell, J.R. Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 2021, 37, 100878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrattan, K.E.; Shell, R.D.; Hurst-Davis, R.; Young, S.D.; O’Brien, E.; Lavrov, A.; Wallach, S.; Lamarca, N.; Reyna, S.P.; Darras, B.T. Patients with Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type 1 Achieve and Maintain Bulbar Function Following Onasemnogene Abeparvovec Treatment. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2023, 10, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berti, B.; Fanelli, L.; Stanca, G.; Onesimo, R.; Palermo, C.; Leone, D.; de Sanctis, R.; Carnicella, S.; Norcia, G.; Forcina, N.; et al. Oral and Swallowing Abilities Tool (OrSAT) in nusinersen treated patients. Arch. Dis. Child. 2022, 107, 912–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weststrate, H.; Stimpson, G.; Thomas, L.; Scoto, M.; Johnson, E.; Stewart, A.; Muntoni, F.; Baranello, G.; Conway, E.; Manzur, A.; et al. Evolution of bulbar function in spinal muscular atrophy type 1 treated with nusinersen. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2022, 64, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, W.M. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalhoff, H.; Kersting, M.; Sinningen, K.; Lücke, T. Development of eating skills in infants and toddlers from a neuropediatric perspective. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2024, 50, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pera, M.C.; Coratti, G.; Pane, M.; Masson, R.; Sansone, V.A.; D’Amico, A.; Catteruccia, M.; Agosto, C.; Varone, A.; Bruno, C.; et al. Type I spinal muscular atrophy and disease modifying treatments: A nationwide study in children born since 2016. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 78, 102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzorni, N.; Valentini, D.; Gilardone, M.; Borghi, E.; Corbo, M.; Schindler, A. The Mealtime Assessment Scale (MAS): Part 1—Development of a Scale for Meal Assessment. Folia Phoniatr. Logop. 2020, 72, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzorni, N.; Valentini, D.; Gilardone, M.; Scarponi, L.; Tresoldi, M.; Barozzi, S.; Corbo, M.; Schindler, A. The Mealtime Assessment Scale (MAS): Part 2—Preliminary Psychometric Analysis. Folia Phoniatr. Logop. 2020, 72, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, B.; Fanelli, L.; de Sanctis, R.; Onesimo, R.; Palermo, C.; Leone, D.; Carnicella, S.; Norcia, G.; Forcina, N.; Coratti, G.; et al. Oral and Swallowing Abilities Tool (OrSAT) for Type 1 SMA Patients: Development of a New Module. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2021, 8, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunieda, K.; Ohno, T.; Fujishima, I.; Hojo, K.; Morita, T. Reliability and validity of a tool to measure the severity of dysphagia: The Food Intake LEVEL Scale. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2013, 46, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glanzman, A.M.; Mazzone, E.; Main, M.; Pelliccioni, M.; Wood, J.; Swoboda, K.J.; Scott, C.; Pane, M.; Messina, S.; Bertini, E.; et al. The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders (CHOP INTEND): Test development and reliability. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2010, 20, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasundaram, P.; Avulakunta, I.D. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, 4th ed.; The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. WISC-V: Technical and Interpretive Manual; NCS Pearson, Incorporated: Bloomington, MN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Astudillo, C.; Brooks, O.; Salabarria, S.M.; Coker, M.; Corti, M.; Lammers, J.; Plowman, E.K.; Byrne, B.J.; Smith, B.K. Longitudinal changes of swallowing safety and efficiency in infants with spinal muscular atrophy who received disease modifying therapies. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2024, 59, 1364–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, J.; Johannsen, J.; Denecke, J.; Weiss, D.; Koseki, J.C.; Nießen, A.; Müller, F.; Nienstedt, J.C.; Flügel, T.; Pflug, C. Flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing in children with type 1 spinal muscular atrophy. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2023, 280, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechmann, A.; Behrens, M.; Dörnbrack, K.; Tassoni, A.; Stein, S.; Vogt, S.; Zöller, D.; Bernert, G.; Hagenacker, T.; Schara-Schmidt, U.; et al. Effect of nusinersen on motor, respiratory and bulbar function in early-onset spinal muscular atrophy. Brain 2023, 146, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pane, M.; Coratti, G.; Sansone, V.A.; Messina, S.; Catteruccia, M.; Bruno, C.; Sframeli, M.; Albamonte, E.; Pedemonte, M.; D’Amico, A.; et al. Type I SMA “new natural history”: Long-term data in nusinersen-treated patients. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2021, 8, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.; Nguo, K.; Yiu, E.M.; Woodcock, I.R.; Billich, N.; Davidson, Z.E. Nutrition outcomes of disease modifying therapies in spinal muscular atrophy: A systematic review. Muscle Nerve 2024, 70, 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergenekon, A.P.; Yilmaz Yegit, C.; Cenk, M.; Gokdemir, Y.; Erdem Eralp, E.; Ozturk, G.; Unver, O.; Kenis Coskun, O.; Karadag Saygi, E.; Turkdogan, D.; et al. Respiratory outcome of spinal muscular atrophy type 1 patients treated with nusinersen. Pediatr. Int. 2022, 64, e15175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechmann, A.; Langer, T.; Schorling, D.; Stein, S.; Vogt, S.; Schara, U.; Kölbel, H.; Schwartz, O.; Hahn, A.; Giese, K.; et al. Evaluation of Children with SMA Type 1 Under Treatment with Nusinersen within the Expanded Access Program in Germany. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2018, 5, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Holanda Mendonça, R.; Jorge Polido, G.; Ciro, M.; Jorge Fontoura Solla, D.; Conti Reed, U.; Zanoteli, E. Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type 1 Treated with Nusinersen. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2021, 8, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, R.; Mazurkiewicz-Bełdzińska, M.; Rose, K.; Servais, L.; Xiong, H.; Zanoteli, E.; Baranello, G.; Bruno, C.; Day, J.W.; Deconinck, N.; et al. Safety and efficacy of risdiplam in patients with type 1 spinal muscular atrophy (FIREFISH part 2): Secondary analyses from an open-label trial. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 1110–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendell, J.R.; Al-Zaidy, S.; Shell, R.; Arnold, W.D.; Rodino-Klapac, L.R.; Prior, T.W.; Lowes, L.; Alfano, L.; Berry, K.; Church, K.; et al. Single-Dose Gene-Replacement Therapy for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zaidy, S.; Pickard, A.S.; Kotha, K.; Alfano, L.N.; Lowes, L.; Paul, G.; Church, K.; Lehman, K.; Sproule, D.M.; Dabbous, O.; et al. Health outcomes in spinal muscular atrophy type 1 following AVXS-101 gene replacement therapy. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2019, 54, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercuri, E.; Muntoni, F.; Baranello, G.; Masson, R.; Boespflug-Tanguy, O.; Bruno, C.; Corti, S.; Daron, A.; Deconinck, N.; Servais, L.; et al. Onasemnogene abeparvovec gene therapy for symptomatic infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy type 1 (STR1VE-EU): An open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 832–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlNaimi, A.; Hamad, S.G.; Mohamed, R.B.A.; Ben-Omran, T.; Ibrahim, K.; Osman, M.F.E.; Abu-Hasan, M. A breakthrough effect of gene replacement therapy on respiratory outcomes in children with spinal muscular atrophy. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2023, 58, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiß, C.; Ziegler, A.; Becker, L.L.; Johannsen, J.; Brennenstuhl, H.; Schreiber, G.; Flotats-Bastardas, M.; Stoltenburg, C.; Hartmann, H.; Illsinger, S.; et al. Gene replacement therapy with onasemnogene abeparvovec in children with spinal muscular atrophy aged 24 months or younger and bodyweight up to 15 kg: An observational cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2022, 6, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Silva, A.M.; Holland, S.; Kariyawasam, D.; Herbert, K.; Barclay, P.; Cairns, A.; MacLennan, S.C.; Ryan, M.M.; Sampaio, H.; Smith, N.; et al. Onasemnogene abeparvovec in spinal muscular atrophy: An Australian experience of safety and efficacy. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2022, 9, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, K.A.; Farrar, M.A.; Muntoni, F.; Saito, K.; Mendell, J.R.; Servais, L.; McMillan, H.J.; Finkel, R.S.; Swoboda, K.J.; Kwon, J.M.; et al. Onasemnogene abeparvovec for presymptomatic infants with two copies of SMN2 at risk for spinal muscular atrophy type 1: The Phase III SPR1NT trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1381–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audic, F.; Barnerias, C. Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) type I (Werdnig-Hoffmann disease). Arch. Pediatr. 2020, 27, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martí, Y.; Aponte Ribero, V.; Batson, S.; Mitchell, S.; Gorni, K.; Gusset, N.; Oskoui, M.; Servais, L.; Deconinck, N.; McGrattan, K.E.; et al. A Systematic Literature Review of the Natural History of Respiratory, Swallowing, Feeding, and Speech Functions in Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA). J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2024, 11, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sanctis, R.; Pane, M.; Coratti, G.; Palermo, C.; Leone, D.; Pera, M.C.; Abiusi, E.; Fiori, S.; Forcina, N.; Fanelli, L.; et al. Clinical phenotypes and trajectories of disease progression in type 1 spinal muscular atrophy. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2018, 28, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Heul, A.M.B.; Wijngaarde, C.A.; Wadman, R.I.; Asselman, F.; Van Den Aardweg, M.T.A.; Bartels, B.; Cuppen, I.; Gerrits, E.; Van Den Berg, L.H.; Van Der Pol, W.L.; et al. Bulbar Problems Self-Reported by Children and Adults with Spinal Muscular Atrophy. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2019, 6, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrattan, K.E.; Keeley, M.; McGhee, H.; Clemmens, C.; Hernandez, K. Natural history of physiologic swallowing deficits in spinal muscular atrophy type 1. Dysphagia 2019, 34, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darras, B.T.; Masson, R.; Mazurkiewicz-Bełdzińska, M.; Rose, K.; Xiong, H.; Zanoteli, E.; Baranello, G.; Bruno, C.; Vlodavets, D.; Wang, Y.; et al. Risdiplam-Treated Infants with Type 1 Spinal Muscular Atrophy versus Historical Controls. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).