Performance Differences Between Spanish AzBio and Latin American HINT: Implications for Test Selection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

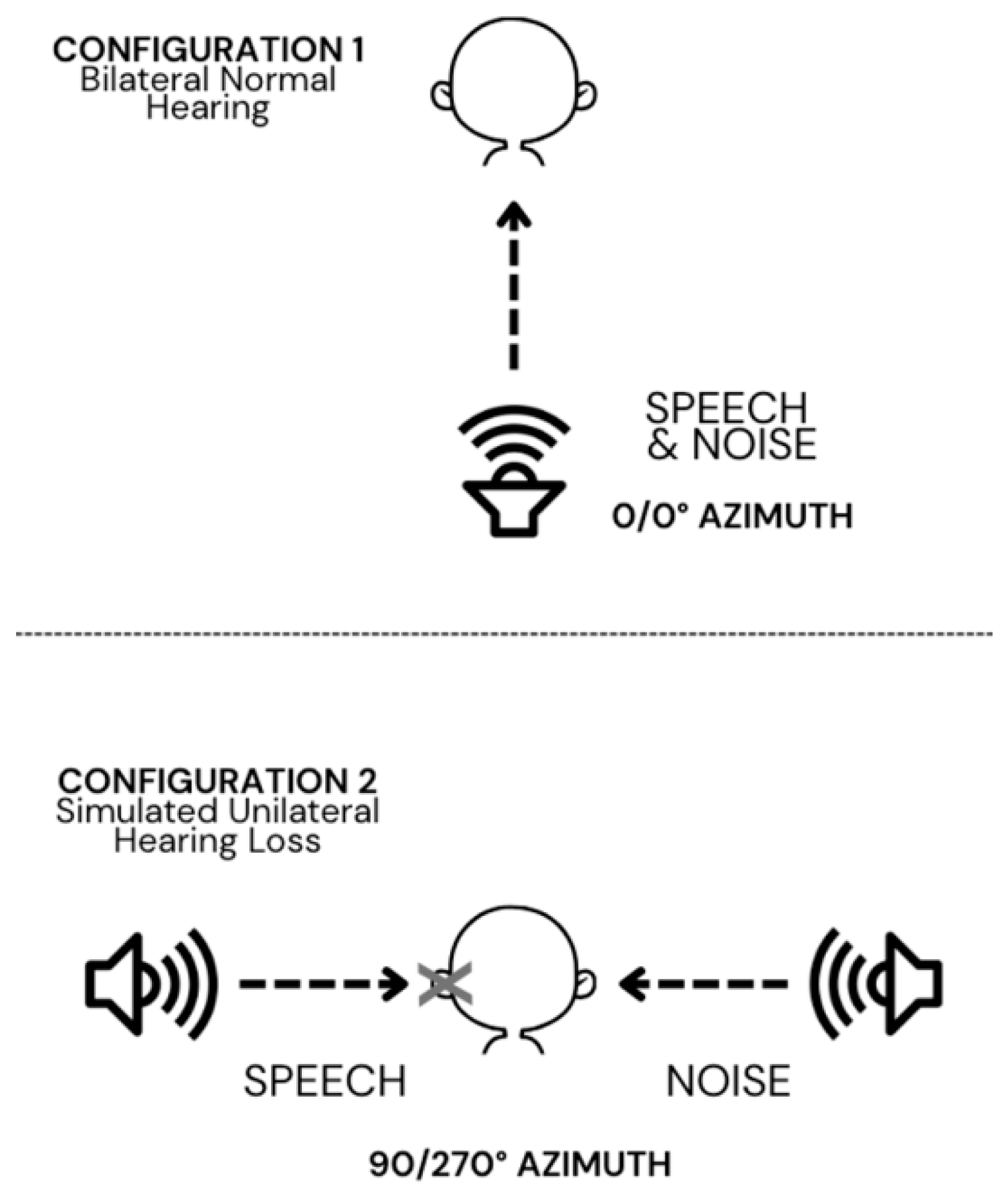

2.2. Speech Perception Testing Conditions

- Bilateral Normal Hearing Condition—Participants were tested with both ears unoccluded and unaided.

- Simulated Unilateral Hearing Loss Condition—A deeply inserted earplug combined with a noise-reducing earmuff was placed on the right ear to simulate unilateral hearing loss, disrupting binaural cues. Of note, this plug and muff configuration resulted in a unilateral, flat moderate hearing loss (mean of 52.5 dB pure tone average; 500–4000 Hz). Monaural testing with contralateral masking was not feasible in this study’s spatially separated speech-in-noise condition because the speech and noise stimuli were already presented through both available audiometer channels. Adding masking would have required a third channel, which was not available on the clinical audiometers used for this study. Therefore, a plug and muff configuration was selected as a practical and clinically accessible method to reduce input to the poorer ear while preserving the intended spatial separation of speech and noise. While this simulation cannot replicate the long-term perceptual and cognitive effects of actual hearing loss, it provides a controlled means of assessing how spatial separation and test type influence performance when binaural hearing is disrupted.

2.3. Test Configurations

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Launch of the World Report on Hearing. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2021/03/03/default-calendar/launch-of-the-world-report-on-hearing (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Nearly 1 in 7 Hispanic/Latino Adults Has Some Hearing Loss. Available online: https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/news/2015/nearly-1-7-hispaniclatino-adults-has-some-hearing-loss (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- U.S. Census Bureau. Hispanic or Latino Origin by Specific Origin: 2020 Census. Available online: https://www.census.gov (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Sanchez, C.; Coto, J.; Alfano, A.; Cejas, I. Paediatric audiology measures for Spanish-speaking patients: Current practice & state of knowledge. Int. J. Audiol. 2023, 63, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbull, M.M.; Martin, B.A.; MacRoy-Higgins, M. Cochlear Implant Evaluations of Spanish-Speaking Adults: A survey. Commun. Disord. Q. 2023, 45, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, A.; Perkins, E.; Rivas, A.; Rincon, L.A.; Litvak, L.; Spahr, T.; Dorman, M.; Kessler, D.; Gifford, R. Development and validation of the Spanish AZBiO Sentence Corpus. Otol. Neurotol. 2020, 42, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soli, S.D.; Vermiglio, A.; Wen, K.; Filesari, C.A. Development of the Hearing in Noise Test (HINT) in Spanish. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2002, 112 (Suppl. 5), 2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velandia, S.; Martinez, D.; Peña, S.; Misztal, C.; Goncalves, S.; Ma, R.; Angeli, S.; Telischi, F.; Holcomb, M.; Dinh, C.T. Speech discrimination outcomes in adult cochlear implant recipients by primary language and bilingual Hispanic patients. Otolaryngology 2023, 170, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spahr, A.J.; Dorman, M.F.; Litvak, L.M.; Van Wie, S.; Gifford, R.H.; Loizou, P.C.; Loiselle, L.M.; Oakes, T.; Cook, S. Development and validation of the AZBiO Sentence lists. Ear Hear. 2011, 33, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, M.; Soli, S.D.; Sullivan, J.A. Development of the Hearing In Noise Test for the measurement of speech reception thresholds in quiet and in noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1994, 95, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, R.H.; Shallop, J.K.; Peterson, A.M. Speech recognition materials and ceiling effects: Considerations for cochlear implant programs. Audiol. Neurotol. 2008, 13, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, R.H.; Dorman, M.F.; Shallop, J.K.; Sydlowski, S.A. Evidence for the expansion of adult cochlear implant candidacy. Ear Hear. 2010, 31, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, E.R.; Shader, M.J. Comparing the AZBio Sentence-in-Noise Test in English and Spanish in bilingual adults. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2025, 35, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holder, J.T.; Levin, L.M.; Gifford, R.H. Speech recognition in noise for adults with normal Hearing: Age-Normative Performance for AZBio, BKB-SIN, and QuickSIN. Otol. Neurotol. 2018, 39, e972–e978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, K.R.; Aarts, N.L. A Comparison of the HINT and Quick SIN Tests. Can. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. Audiol. 2006, 30, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Smeal, M.R.; Coto, J.; Prentiss, S.; Stern, T.; VanLooy, L.; Holcomb, M.A. Cochlear implant referral Criteria for the Spanish-Speaking Adult population. Otol. Neurotol. 2023, 45, e71–e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velandia, S.L.; Prentiss, S.M.; Martinez, D.M.; Sanchez, C.M.; Laffitte-Lopez, D.; Snapp, H.A. Classification performance of Spanish and English word recognition testing to identify cochlear implant candidates. Int. J. Audiol. 2024, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holcomb, M.A.; Williams, E.; Prentiss, S.; Sanchez, C.M.; Smeal, M.R.; Stern, T.; Tolen, A.K.; Velandia, S.; Coto, J. Utilization of the Spanish bisyllable word recognition Test to assess cochlear implant performance trajectory. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manrique, M.; Ramos, Á.; De Paula Vernetta, C.; Gil-Carcedo, E.; Lassaletta, L.; Sanchez-Cuadrado, I.; Espinosa, J.M.; Batuecas, Á.; Cenjor, C.; Lavilla, M.J.; et al. Guideline on cochlear implants. Acta Otorrinolaringológica Española 2018, 70, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manrique, M.; Zubicaray, J.; De Erenchun, R.I.; Huarte, A.; Manrique-Huarte, R. Guidelines for cochlear implant indication in Navarre. An. Del Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2015, 38, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejas, I.; Sanchez, C.; Lochet, D.; Coto, J.; Flores, G. Cochlear Implant Management and Considerations for Bilingual Families. In Pediatric Cochlear Implants; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | 34.29 (8.98) |

| Sex Female Male | 17 (81%) 4 (19%) |

| Highest level of education High school or GED Some college, no degree Associate’s degree Bachelor’s degree Master’s degree Doctoral degree | 1 (4.8%) 3 (14.3%) 2 (9.5%) 5 (23.8%) 1 (4.8%) 9 (42.9%) |

| Ethnicity Non-Hispanic Hispanic | 2 (9.5%) 19 (90.5%) |

| Race White | 21 (100%) |

| Participant Birth Country USA Other Brazil Colombia Cuba Dominican Republic France Venezuela | 13 (61.9%) 8 (38.1%) 1 3 1 1 1 1 |

| Maternal Birth Country USA Other Brazil Colombia Cuba Dominican Republic El Salvador France Nicaragua Venezuela | 2 (9.5%) 19 (90.5%) 1 5 3 1 1 1 5 1 |

| First language spoken English Spanish Other | 2 (9.5%) 17 (81%) 2 (9.5%) |

| Primary language spoken English Spanish Other | 14 (66.7%) 6 (28.6%) 1 (4.8%) |

| Language Dominance English dominant, Spanish secondary Spanish dominant, English secondary Equal language dominance Other language dominant | 11 (52.4%) 3 (14.3%) 6 (28.6%) 1 (4.8%) |

| Mean (SD) | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAzB0 + 10 LAH0 + 10 | 97.15 (4.69) 100.00 (0.00) | −2.72 | 0.01 |

| SAzB0 + 5 LAH0 + 5 | 93.60 (6.17) 100.00 (0.00) | −4.64 | 0.001 |

| SAzB0 + 0 LAH0 + 0 | 71.75 (13.11) 100.00 (0.00) | −9.64 | 0.001 |

| SAzB90 + 10 LAH90 + 10 | 83.55 (14.15) 100.00 (0.00) | −5.20 | 0.001 |

| SAzB90 + 5 LAH90 + 5 | 68.90 (17.05) 99.85 (0.67) | −8.19 | 0.001 |

| SAzB90 + 0 LAH90 + 0 | 22.74 (11.56) 91.84 (10.81) | −27.16 | 0.001 |

| Spanish Dominant, English Secondary (n = 3) Mean (SD) | Equal Language Dominance (n = 6) Mean (SD) | English Dominant, Spanish Secondary (n = 10) Mean (SD) | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAzB0 + 5 | 99.33 (0.58) | 97.17 (2.32) | 90.2 (6.53) | 5.63 | 0.01 |

| SAzB0 + 0 | 82.67 (8.08) | 79.17 (8.28) | 65.5 (12.89) | 4.34 | 0.03 |

| SAzB90 + 10 | 95.33 (3.79) | 94.0 (5.18) | 74.3 (13.68) | 8.34 | 0.01 |

| SAzB90 + 5 | 84 (3.46) | 80.50 (8.09) | 57.10 (15.91) | 8.78 | 0.01 |

| SAzB90 + 0 | 31.67 (5.51) | 25.67 (15.02) | 15.50 (7.03) | 3.79 | 0.05 |

| Spanish Dominant, English Secondary Mean (SD) (n = 3) | Equal Language Dominance Mean (SD) (n = 6) | English Dominant, Spanish Secondary Mean (SD) (n = 10) | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAH + 0 | 100.00 (0.00) | 100.00 (0.00) | 99.30 (1.25) | 1.32 | 0.30 |

| LAH90 + 5 | 100.00 (0.00) | 100.00 (0.00) | 99.7 (0.95) | 0.42 | 0.66 |

| LAH90 + 0 | 100.00 (0.00) | 96.40 (4.62) | 87.70 (12.95) | 2.23 | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sanchez, C.M.; Coto, J.; Velandia, S.; Cejas, I.; Holcomb, M.A. Performance Differences Between Spanish AzBio and Latin American HINT: Implications for Test Selection. Audiol. Res. 2025, 15, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15050129

Sanchez CM, Coto J, Velandia S, Cejas I, Holcomb MA. Performance Differences Between Spanish AzBio and Latin American HINT: Implications for Test Selection. Audiology Research. 2025; 15(5):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15050129

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanchez, Chrisanda Marie, Jennifer Coto, Sandra Velandia, Ivette Cejas, and Meredith A. Holcomb. 2025. "Performance Differences Between Spanish AzBio and Latin American HINT: Implications for Test Selection" Audiology Research 15, no. 5: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15050129

APA StyleSanchez, C. M., Coto, J., Velandia, S., Cejas, I., & Holcomb, M. A. (2025). Performance Differences Between Spanish AzBio and Latin American HINT: Implications for Test Selection. Audiology Research, 15(5), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15050129