Auditory Processing and Speech Sound Disorders: Behavioral and Electrophysiological Findings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Participant Recruitment and Language and Auditory Processing Assessment

2.3. Electrophysiological Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Summary of Demographic and Behavrioral AP Assessment Findings

- -

- The Speech in Babble test [67] at S/N form −1 and 3 (with the −1 condition being when the noise level exceeds that of speech by 5 dB).

- -

- Temporal processing, frequency perception, and dichotic listening tests from the auditory processing assessment battery.

- -

- Grammar, specifically the use of prepositional phrases from the language battery.

- -

- Immediate word repetition and initial phoneme deletion from the phonology battery.

3.2. Group Comparisons

Binary Logistic Regression and Correlations

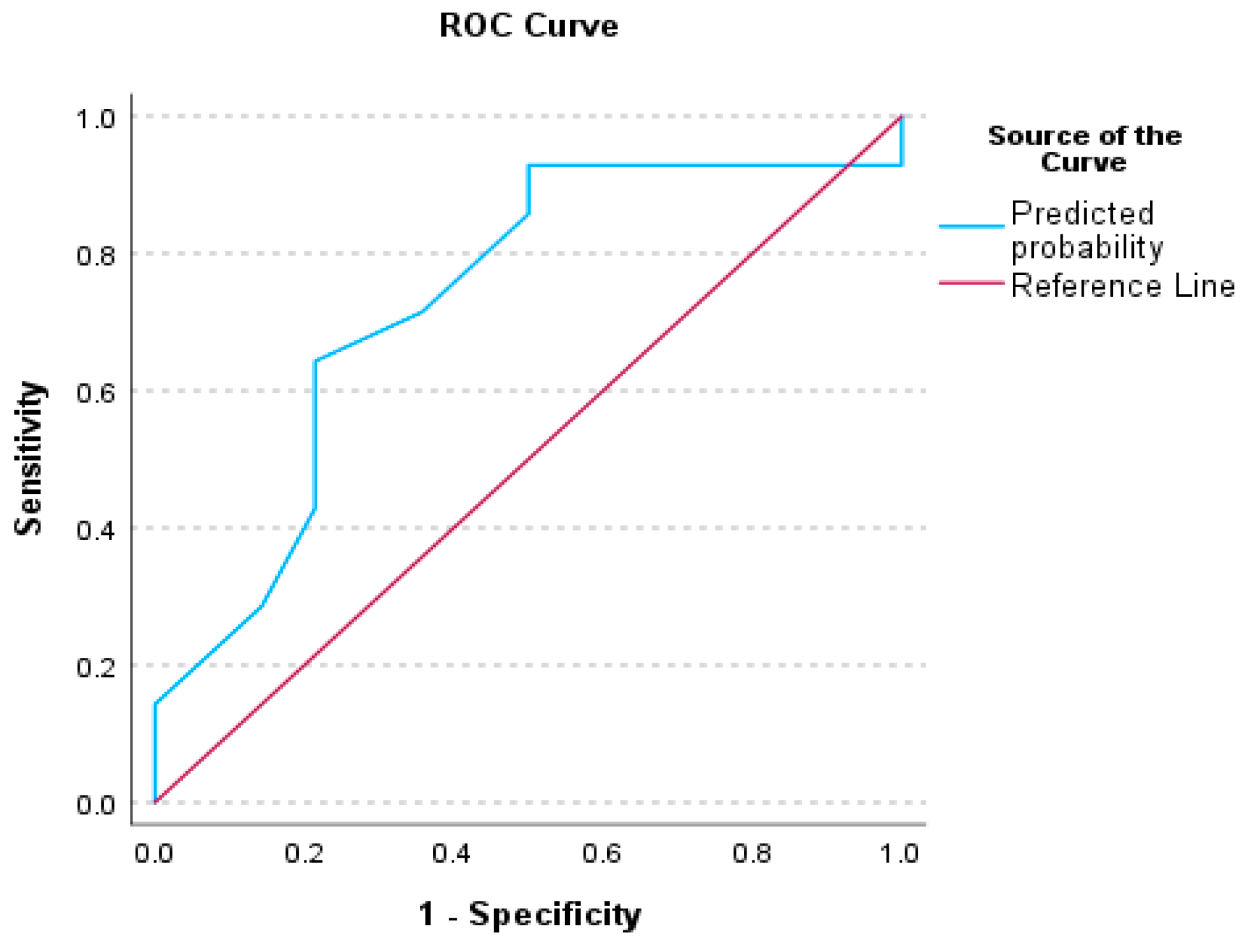

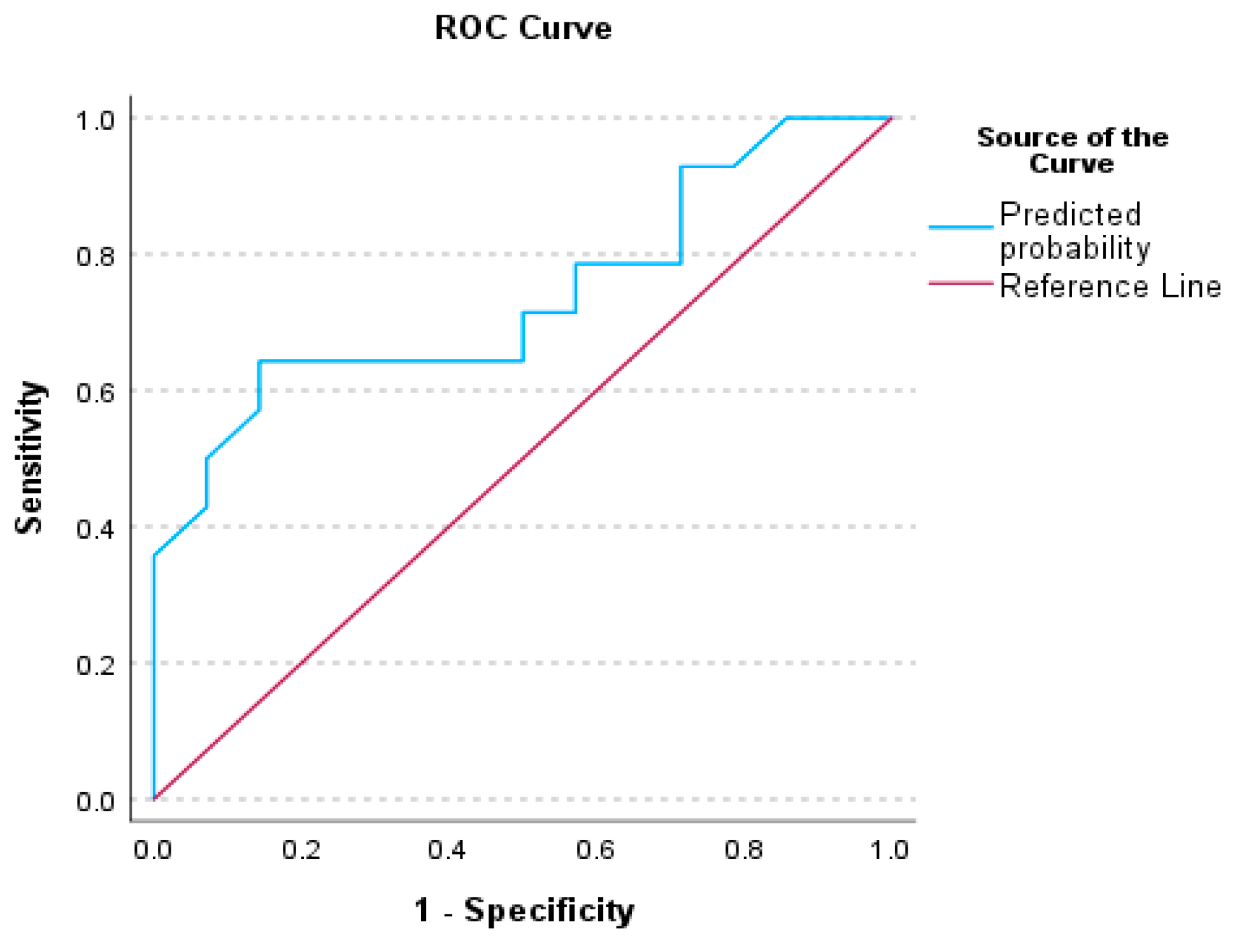

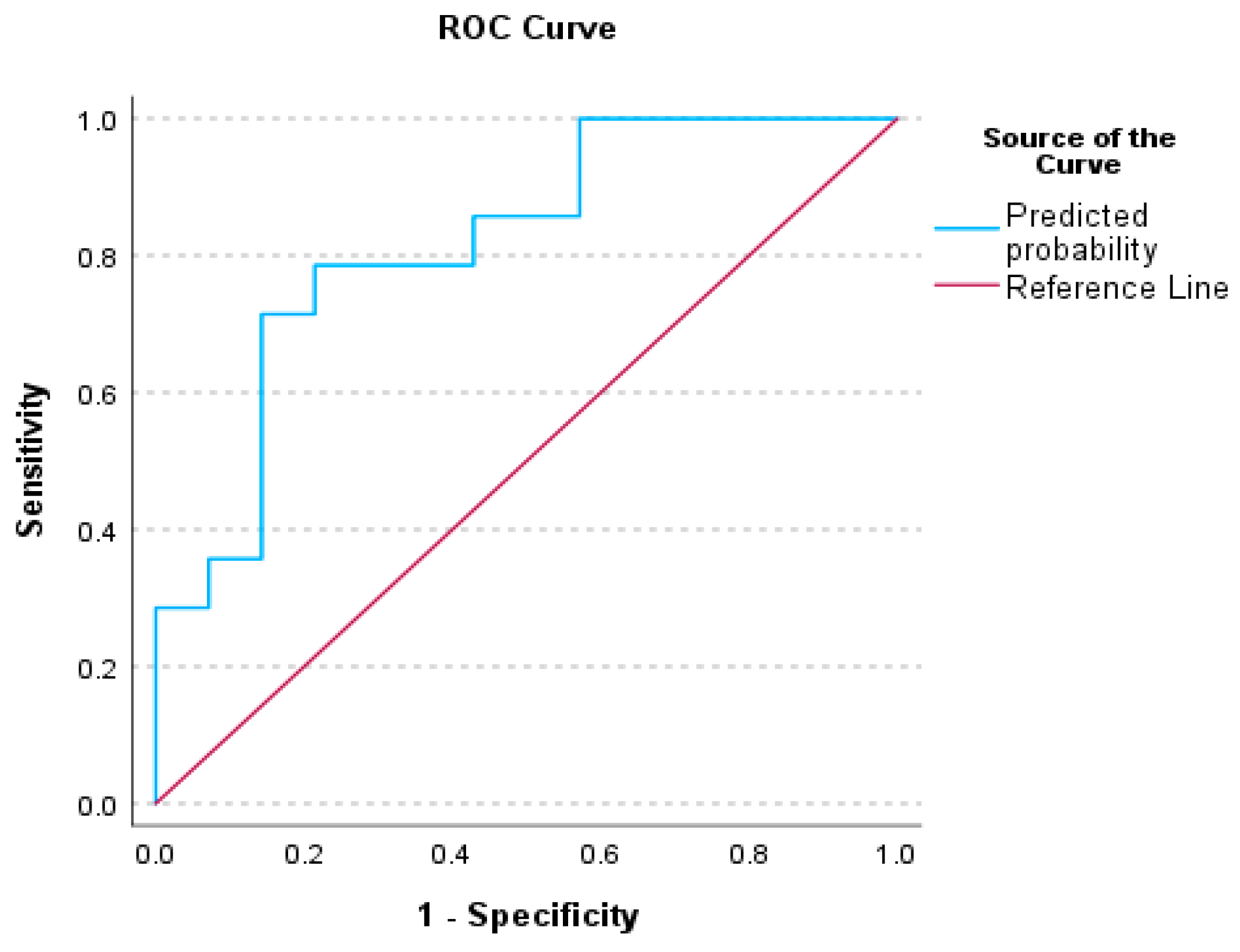

3.3. Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) Analysis for Auditory Processing Tests

4. Discussion

4.1. Receiver Operative Characteristics (ROC) for Auditory Behavioral Scores

4.2. Electrophysiological Assessment and Auditory Processing Correlations

4.3. Limitations and Future Extensions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Experimental Group Children (n = 14) | TD Children (n = 14) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mdn (IQR) | Mdn (IQR) | Mann–Whitney U | p | n2 | |

| ABR measures | |||||

| ABR RIGHT IPSILATΕRAL V MS | 6.05 (5.74–6.28) | 6.05 (5.99–6.26) | 79.00 | 0.593 | 0.007 |

| ABR RIGHT IPSILATΕRAL I–V MS | 3.5 (2.5–4.4) | 4.2 (3.2–5.7) | 52.50 | 0.072 | 0.083 |

| ABR RIGHT CONTROLATΕRAL V MS | 6.15 (6.05–6.31) | 6.10 (6.05–6.36) | 84.50 | 0.787 | 0.01 |

| ABR RIGHT CONTROLATΕRAL I–V MS | 2.6 (1.9–3.4) | 2.7 (2.0–3.7) | 81.00 | 0.666 | 0.004 |

| ABR LEFT IPSILATΕRAL V MS | 6.05 (5.89–6.28) | 6.00 (5.84–6.15) | 81.00 | 0.663 | 0.004 |

| ABR LEFT CONTROLATΕRAL V MS | 6.15 (5.94–6.38) | 5.95 (5.94–6.15) | 70.00 | 0.325 | 0.003 |

| ABR LEFT CONTROLATΕRAL I–V MS | 2.4 (1.6–3.5) | 3.3 (1.1–4.4) | 70.50 | 0.350 | 0.003 |

| MLR measures | |||||

| MLR RIGHT IPSILATΕRAL AMPLITUDE Na | −0.14 (−0.26–0.04) | −0.01 (−0.32–0.14) | 67.50 | 0.280 | 0.029 |

| MLR RIGHT CONTROLATΕRAL AMPLITUDE Na | −0.11 (−0.25–−0.01) | 0.00 (−0.20–0.11) | 88.00 | 0.924 | 0.023 |

| MLR LEFT IPSILATΕRAL AMPLITUDE Na | −0.11 (−0.21–−0.06) | −0.16 (−0.36–−0.07) | 63.50 | 0.204 | 0.041 |

| MLR LEFT CONTROLATΕRAL AMPLITUDE Na | −0.12 (−0.21–0.01) | 0.47 (0.03–0.08) | 73.00 | 0.415 | 0.017 |

| LLR measures | |||||

| LLR_RIGHT_IPSILATERAL_TIME_P1 | 78.43 (68.43–87.60) | 73.43 (60.10–80.10) | 50.50 | 0.119 | 0.006 |

| LLR_RIGHT_IPSILATERAL_TIME_P2 | 175.10 (151.34–235.51) | 165.93 (148.43–195.93) | 59.50 | 0.479 | 0.012 |

| LLR_RIGHT_IPSILATATERAL_AMPLITUDE_P1 | 0.79 (0.41–0.93) | 1.09 (0.93–1.28) | 28.00 | =0.05 | 0.192 |

| LLR RIGHT IPSILATERAL AMPLITUDE P2 | 0.25 (−0.15–1.07) | 0.32 (−0.18–1.29) | 67.00 | 0.978 | 0.01 |

| LLR RIGHT CONTROLATERAL TIME P1 | 81.76 (69.68–88.43) | 72.60 (63.43–80.93) | 72.50 | 0.077 | 0.082 |

| LLR RIGHT CONTROLATERAL TIME P2 | 175.93 (155.10–231.35) | 162.60 (148.43–183.43) | 81.00 | 0.329 | 0.026 |

| LLR RIGHT CONTROLATERAL AMPLITUDE P1 | 0.98 (0.60–1.82) | 1.42 (1.15–1.72) | 60.00 | 0.182 | 0.048 |

| LLR RIGHT CONTROLATERAL AMPLITUDE P2 | 0.33 (−0.86–0.89) | 0.92 (−0.28–1.82) | 74.00 | 0.187 | 0.047 |

| LLR LEFT IPSILATERAL TIME P1 | 81.77 (69.27–86.75) | 71.76 (56.76–84.68) | 62.50 | 0.241 | 0.036 |

| LLR LEFT IPSILATERAL TIME P2 | 160.10 (142.60–182.18) | 155.10 (140.09–195.52) | 62.50 | 0.979 | 0.01 |

| LLR LEFT IPSILATERAL AMPLITUDE P1 | 0.89 (0.29–1.32) | 1.33 (0.87–1.83) | 56.00 | 0.150 | 0.055 |

| LLR LEFT IPSILATERAL AMPLITUDE P2 | 0.31 (0.63–0.97) | 0.23 (−0.29–1.00) | 70.00 | 0.660 | 0.05 |

| LLR LEFT CONTROLATERAL TIME P1 | 77.60 (69.27–88.00) | 72.60 (60.51–78.01) | 78.00 | 0.109 | 0.066 |

| LLR LEFT CONTROLATERAL TIME P2 | 167.60 (159.27–197.60) | 150.10 (145.93–188.84) | 49.50 | 0.285 | 0.003 |

| LLR LEFT CONTROLATERAL AMPLITUDE P2 | 0.56 (0.35–0.87) | 0.30 (−0.56–1.02) | 45.00 | 0.567 | 0.009 |

References

- Souza, M.A.; Passaglio, N.D.; Lemos, S.M. Language and auditory processing disorders: Literature review. Rev. CEFAC 2016, 18, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, E.A.; Gonçalves, L.F.; Blanco-Dutra, A.P.; Paiva, K.M.; Stolz, J.V.; Haas, P. Impact of the central auditory processing disorder on children with phonological deviation: A systematic review. Rev. Assoc. Médica Bras. 2021, 67, 1204–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tervaniemi, M.; Hugdahl, K. Lateralization of auditory-cortex functions. Brain Res. Rev. 2003, 43, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M.W. Understanding the role of the prefrontal cortex in phonological processing. Clin. Linguist. Phon. 2009, 23, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo, J.H.; Rosen, S.; Bamiou, D.E. Auditory training effects on the listening skills of children with auditory processing disorder. Ear Hear. 2016, 37, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tse, S.M.; Ingram, D. Phonological Development in Young Children. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 1978, 7, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wren, Y.; Harding, S.; Goldbart, J.; Roulstone, S. A systematic review and classification of interventions for speech-sound disorder in preschool children. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2018, 53, 446–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharani, P.N.; Afifah, N.; Lubis, Y. The Power of Phonology: Analyzing the Impact of Sound Structure on Language. J. Engl. Lang. Teach. Learn. 2023, 4, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bamiou, D.E.; Musiek, F.E.; Luxon, L.M. Aetiology and clinical presentations of auditory processing disorders—A review. Arch. Dis. Child 2001, 85, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hind, S.E.; Haines-Bazrafshan, R.; Benton, C.L.; Brassington, W.; Towle, B.; Moore, D.R. Prevalence of clinical referrals having hearing thresholds within normal limits. Int. J. Audiol. 2011, 50, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, K.; Riegner, T.; Padilla, J.; Greenwood, L.A.; Loson, J.; Zavala, S.; Morlet, T. Prevalence of auditory processing disorder in school-aged children in the Mid-Atlantic region. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2016, 27, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imhof, M.; Henning, N.; Kreft, S. Effects of backround noise on cognitive performance in elementary school children. List. Educ. 2009, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Iliadou, V.; Ptok, M.; Grech, H.; Pedersen, E.R.; Brechmann, A.; Deggouj, N.; Kiese-Himmel, C.; Śliwińska-Kowalska, M.; Nickisch, A.; Demanez, L.; et al. A European perspective on auditory processing disorder-current knowledge and future research focus. Front. Neurol. 2017, 28, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Purdy, S.C.; Kelly, A.S. Comorbidity of auditory processing, language, and reading disorders. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2009, 52, 706–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçınkaya, F.; Muluk, N.B.; Şahin, S. Effects of listening ability on speaking, writing and reading skills of children who were suspected of auditory processing difficulty. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2009, 73, 1137–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalnak, N.; Nakeva von Mentzer, C. Listening and Processing Skills in Young School Children with a History of Developmental Phonological Disorder. Healthcare 2024, 12, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.R.; Ferguson, M.A.; Edmondson-Jones, A.M.; Ratib, S.; Riley, A. Nature of auditory processing disorder in children. Pediatrics 2010, 126, e382–e390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieńkowska, K.; Gos, E.; Skarżyński, P.H. Psychometric properties of the Polish version of the Children’s Auditory Performance Scale. Med. Ogólna I Nauk. O Zdrowiu 2020, 26, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.D.; Nunes, A.D.; Farias, T.R.; Santos, A.B.; Taveira, K.V.; Balen, S.A. Accuracy of screening instruments in identifying central auditory processing disorders: An integrative literature review. Rev. CEFAC 2021, 23, e11720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, M.I.; Casali, R.L.; Boscariol, M.; Lunardi, L.L.; Guerreiro, M.M.; Colella-Santos, M.F. Temporal auditory processing and phonological awareness in children with benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 256340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, C.; Priya, M.B.; Joshi, K. Relationship between temporal processing and phonological awareness in children with speech sound disorders. Clin. Linguist. Phon. 2020, 34, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, A.E.; Hood, L.J.; Cullen, J.K., Jr.; Cranford, J. Click ABR characteristics in children with temporal processing deficits. J. Educ. Audiol. 2008, 14, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Iliadou, V.; Bamiou, D.E. Psychometric evaluation of children with auditory processing disorder (APD): Comparison with normal-hearing and clinical non-APD groups. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2012, 55, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerger, J.; Musiek, F. Report of the consensus conference on the diagnosis of auditory processing disorders in school-aged children. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2000, 11, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, A.C.; Silva, L.A.F.; Barrozo, T.F.; Leite, R.A.; Wertzner, H.F.; Matas, C.G. Neuronal plasticity of the auditory pathway in children with speech sound disorder: A study of Long-Latency Auditory Evoked Potentials. CoDAS 2021, 33, e20200145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, T.S.; Follestad, T.; Andersson, S.; Lind, O.; Øygarden, J.; Nordgård, S. Normative data for diagnosing auditory processing disorder in Norwegian children aged 7–12 years. Int. J. Audiol. 2018, 57, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosos, K.; Papanicolaou, A.; Voniati, L.; Panayidou, K.; Thodi, C. Auditory Processing and Speech-Sound Disorders. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagacé, J.; Jutras, B.; Gagné, J.P. Auditory processing disorder and speech perception problems in noise: Finding the underlying origin. Am. J. Audiol. 2010, 19, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Muniz, C.N.; Befi-Lopes, D.M.; Schochat, E. Investigation of auditory processing disorder and language impairment using the speech-evoked auditory brainstem response. Hear. Res. 2012, 294, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermiglio, A.J. On the clinical entity in audiology:(Central) auditory processing and speech recognition in noise disorders. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2014, 25, 904–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, R.O.; Kumar, P.; Singh, N.K. Subcortical and cortical electrophysiological measures in children with speech-in-noise deficits associated with auditory processing disorders. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2022, 65, 4454–4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhu, H.; Chen, M.; Hong, Q.; Chi, X. Electrophysiological screening for children with suspected auditory processing disorder: A systematic review. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 692840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, N.; Barrozo, T.F.; de Oliveira Pagan-Neves, L.; Sanches, S.G.; Wertzner, H.F.; Carvallo, R.M. The influence of (central) APD on the severity of speech-sound disorders in children. Clinics 2016, 71, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintas, V.G.; Attoni, T.M.; Keske-Soares, M.; Mezzomo, C.L. Processamento auditivo e consciência fonológica em crianças com aquisição de fala normal e desviante. Pró-Fono Rev. Atualização Cient 2010, 22, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vilela, N.; Wertzner, H.F.; Sanches, S.G.; Neves-Lobo, I.F.; Carvallo, R.M. Temporal processing in children with phonological disorders submitted to auditory training: A pilot study. J. Soc. Bras 2012, 24, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, E.; van Dijk, P.; Hanekamp, S.; Visser-Bochane, M.I.; Steenbergen, B.; van der Schans, C.P.; Luinge, M.R. Same or different: The overlap between children with auditory processing disorders and children with other developmental disorders: A systematic review. Ear Hear. 2018, 39, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pugh, K.R.; Landi, N.; Preston, J.L.; Mencl, W.E.; Austin, A.C.; Sibley, D.; Frost, S.J. The relationship between phonological and auditory processing and brain organization in beginning readers. Brain Lang. 2013, 125, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, C. A systematic review of auditory processing abilities in children with speech sound disorders. J. Hear. Sci. 2023, 13, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, R.A.; Wertzner, H.F.; Matas, C.G. Long latency auditory evoked potentials in children with phonological disorder. Pró-Fono Rev. De Atualização Científica 2010, 22, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearnshaw, S.; Baker, E.; Munro, N. The speech perception skills of children with and without speech sound disorder. J. Commun. Disord. 2018, 71, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, M.F.; Cremasco, E.B.; Silva, L.M.; Berti, L.C. Auditory-perceptual performance in children with and without phonological disorder in the stops class. InCodas 2021, 33, e20190248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearnshaw, S.; Baker, E.; Munro, N. Speech perception skills of children with speech sound disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2019, 62, 3771–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, E.; Visser-Bochane, M.I.; Steenbergen, B.; van Dijk, P.; van der Schans, C.P.; Luinge, M.R. Characteristics of auditory processing disorders: A systematic review. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res 2016, 59, 384–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geffner, D.; Ross-Swain, D. The Speech-Language Pathologist’s Role in the Assessment of Auditory Processing Skills. In Auditory Processing Disorders: Assessment, Management, and Treatment; Plural Publishing Inc.: San Diego, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 181–213. [Google Scholar]

- Iliadou, V.V.; Chermak, G.D.; Bamiou, D.E.; Musiek, F.E. Gold standard, evidence-based approach to diagnosing APD. Hear. J. 2019, 72, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (Central) Auditory Processing Disorders—The Role of the Audiologist. Available online: https://www.asha.org/policy/ps2005-00114/ (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Richard, G.J. The role of the speech-language pathologist in identifying and treating children with auditory processing disorder. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2011, 42, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, P.; Allan, C. Auditory processing disorders: Relationship to cognitive processes and underlying auditory neural integrity. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2014, 78, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggu, A.R.; Yu, Y.; Overath, T. The click-evoked auditory brainstem response is not affected in auditory processing disorder: A meta-analysis systematic review. Front. Audiol. Otol. 2024, 2, 1369716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfins, M.D.; Colella-Santos, M.F. A review of the clinical applicability of speech-evoked auditory brainstem responses. J. Hear. Sci. 2016, 6, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.; Lodhia, V.; Hautus, M.J. Electrophysiological indices of amplitude modulated sounds and sensitivity to noise. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2019, 139, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouillon, I.; de Lamaze, A.; Ribot, M.; Collet, G.; de Bollardière, T.; Elmir, R.; Parodi, M.; Achard, S.; Denoyelle, F.; Loundon, N. Auditory processing disorder in children: The value of a multidisciplinary assessment. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2021, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeranna, S.A.; Allan, C.; Allen, P. Assessment of cochlear electrophysiology in typically developing children and children with auditory processing disorder. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021, 151, 110962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidvar, S.; Duquette-Laplante, F.; Bursch, C.; Jutras, B.; Koravand, A. Assessing auditory processing in children with listening difficulties: A pilot study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, M. The N1 response and its applications. Audiol. Neurotol. 1997, 2, 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, J.L.; Cone-Wesson, B.K.; Shepherd, R. Maturation of the cortical auditory evoked potential in infants and young children. Hear. Res. 2006, 212, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čeponienė, R.; Cummings, A.; Wulfeck, B.; Ballantyne, A.; Townsend, J. Spectral vs. temporal auditory processing in specific language impairment: A developmental ERP study. Brain Lang. 2009, 110, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrozo, T.F.; Silva, L.A.; Matas, C.G.; Wertzner, H.F. The Relationship between Speech Sound Disorder and Cortical Auditory Evoked Potential. Folia Phoniatr. Logop. 2024, 76, 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosos, K.; Tafiadis, D.; Voniati, L.; Papanicolaou, A.; Thodi, C. Preliminary Validation of the Children’s Auditory Performance Scale (CHAPS) and the Auditory Processing Domain Questionnaire (APDQ) in Greek Cypriot Children. Audiol. Res. 2024, 14, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Audiology. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management of Children and Adults with Central APD. Available online: https://www.audiology.org/practice-guideline/clinical-practice-guidelines-diagnosis-treatment-and-management-of-children-and-adults-with-central-auditory-processing-disorder/ (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- British Society of Audiology (BSA). Position Statement and Practice Guidance: Auditory Processing Disorder (APD). Available online: https://www.thebsa.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Position-Statement-and-Practice-Guidance-APD-2018.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Keith, W.J.; Purdy, S.C.; Baily, M.R.; Kay, F.M. New Zealand Guidelines on Auditory Processing Disorder; New Zealand Audiological Society: Auckland, New Zealand, 2019; pp. 28–55. [Google Scholar]

- Tabone, N.; Grech, H.; Bamiou, D.E. Contentious issues related to auditory processing disorder. Malta J. Health Sci. 2020, 7, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, E.E.; Smart, J.L.; Boiano, J.A.; Bragg, L.E.; Colon, T.N.; Hanson, E.M.; Emanuel, D.C.; Kelly, A.S. Assessing auditory processing abilities in typically developing school-aged children. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2016, 27, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keith, R.W. SCAN C: Test for Auditory Processing Disorders in Children; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Musiek, F.E.; Shinn, J.B.; Jirsa, R.; Bamiou, D.E.; Baran, J.A.; Zaida, E. GIN (Gaps-In-Noise) test performance in subjects with confirmed central auditory nervous system involvement. Ear Hear. 2005, 26, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiras, C.; Iliadou, V.V.; Chermak, G.D.; Nimatoudis, I. Assessment of functional hearing in Greek-speaking children diagnosed with central auditory processing disorder. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2016, 27, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiek, F.E.; Baran, J.A.; Pinheiro, M.L. Neuroaudiology: Case Studies; Singular Publishing Group: San Diego, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Vogindroukas, I.; Protopapas, A.; Stavrakaki, S. Action Pictures Test; Glafki: Chania, Greece, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Giannetopoulou, A.; Kirpotin, L. Metaphon Test; Konstantaras: Athens, Greece, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sideridis, G.; Antoniou, F.; Mouzaki, A.; Simos, P. Raven’s Coloured Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary; Motivo: Athens, Greece, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.e3diagnostics.com/products/abr---assr/vivosonic-integrity-v500 (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Harris, J.K. Primer on binary logistic regression. Fam. Med. Community Health 2021, 9, e001290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pituch, K.A.; Stevens, J.P. Binary logistic regression. In Applied Multivariate Statistics For The Social Sciences; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 434–470. [Google Scholar]

- IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2021.

- Ponterotto, J.G.; Ruckdeschel, D.E. An overview of coefficient alpha and a reliability matrix for estimating adequacy of internal consistency coefficients with psychological research measures. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2007, 105, 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, E.; Ohtamaa, L. Listening Difficulties in children with Developmental Phonological Disorder: A Survey of Parents’ Perception of Their Children’s Listening Abilities. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1286067/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Bishop, D.V.; Snowling, M.J. Developmental dyslexia and specific language impairment: Same or different? Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 858–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawes, P.; Bishop, D. Auditory processing disorder in relation to developmental disorders of language, communication and attention: A review and critique. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2009, 44, 440–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmmed, A.U.; Ahmmed, A.A. Setting appropriate pass or fail cut-off criteria for tests to reflect real life listening difficulties in children with suspected auditory processing disorder. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol 2016, 84, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, L.; Lam, E. Evaluation of screening instruments for auditory processing disorder (APD) in a sample of referred children. Aust. N. Z. J. Audiol 2007, 29, 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bellis, T.J. Assessment and Management of Central Auditory Processing Disorders in the Educational Setting: From Science to Practice; Plural Publishing: San Diego, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, D.R.; Sieswerda, S.L.; Grainger, M.M.; Bowling, A.; Smith, N.; Perdew, A.; Eichert, S.; Alston, S.; Hilbert, L.W.; Summers, L.; et al. Referral and diagnosis of developmental auditory processing disorder in a large, United States hospital-based audiology service. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2018, 29, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankmnal-Veeranna, S.; Allan, C.; Allen, P. Auditory brainstem responses in children with auditory processing disorder. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2019, 30, 904–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkach, J.A.; Chen, X.; Freebairn, L.A.; Schmithorst, V.J.; Holland, S.K.; Lewis, B.A. Neural correlates of phonological processing in speech sound disorder: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Brain Lang. 2011, 119, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abrams, D.A.; Nicol, T.; Zecker, S.G.; Kraus, N. Auditory brainstem timing predicts cerebral asymmetry for speech. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 11131–11137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinn, L.K.; Zhukova, M.A.; Kroeger, R.J.; Ledesma, L.M.; Cavitt, J.E.; Grigorenko, E.L. Auditory brainstem response deficits in learning disorders and developmental language disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidvar, S.; Guijo, L.M.; Duda, V.; Costa-Faidella, J.; Escera, C.; Koravand, A. Can auditory evoked responses elicited to click and/or verbal sound identify children with or at risk of central auditory processing disorder: A scoping review. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2023, 171, 111609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morlet, T.; Nagao, K.; Greenwood, L.A.; Cardinale, R.M.; Gaffney, R.G.; Riegner, T. Auditory event-related potentials and function of the medial olivocochlear efferent system in children with auditory processing disorders. Int. J. Audiol. 2019, 58, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, Z.; Malayeri, S.; Rostami, R. Subcortical encoding of speech cues in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2015, 126, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purdy, S.C.; Kelly, A.S. Cortical auditory evoked potential testing in infants and young children. N. Z. Audiol. Soc. Bull. 2001, 11, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, I.C.; Wertzner, H.F.; Samelli, A.G.; Matas, C.G. Speech and non-speech processing in children with phonological disorders: An electrophysiological study. Clinics 2011, 66, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.R.; Vesole, A.S.; Lin, L.; Caldwell-Kurtzman, J.; Hunter, L.L. Medical Risk Factors Associated with Listening Difficulties in Children. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Test | Stimulus Type | Stim. Intensity | Presentation Rate | Filter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABR | Click | 60 dBnHL | 37.7/s | 10–1500 Hz |

| MLR | Click | 60 dBnHL | 5.7/s | 10–100 Hz |

| LLR | 1000 Hz tone | 60 dBnHL | 1.1/s | 1–15 Hz |

| Factors | Cronbach α |

|---|---|

| Factor 1—CHAPS | 0.60 |

| Factor 5—PHONOLOGY | 0.779 |

| Factor 13—ABR-wV | 0.821 |

| χ2 | p | R2 | Wald | OR | 95%CI | Model Prediction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1—CHAPS | 5.754 | 0.016 | 0.186 | 4.539 | 29.276 | 1.310–654.094 | 71.4% |

| Factor 5—PHONOLOGY | 5.111 | 0.024 | 0.167 | 4.129 | 0.577 | 0.339–0.981 | 67.9% |

| Factor 13—ABR wV | 5.209 | 0.022 | 0.170 | 4.094 | 1.0 × 10−4 | 2.0 × 10−8–0.753 | 60.7% |

| Correlations | r | p |

|---|---|---|

| Factor 1—CHAPS and Factor 13 ABR wV | −0.141 * | 0.475 |

| Factor 1—CHAPS and Factor 5—PHONOLOGY | −0.251 ** | −0.197 |

| Factor 5—PHONOLOGY and Factor 13—ABR wV | 0.385 ** | 0.043 |

| AUC | AUC (95%CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1—CHAPS | 0.740 | (0.545–0.935) | 0.016 |

| Factor 5—PHONOLOGY | 0.730 | (0.535–0.924) | 0.021 |

| Factor 13—ABR wV | 0.737 | (0.547–0.928) | 0.015 |

| Factor 1—CHAPS & Factor 13—ABR-wV | 0.816 | (0.657–0.975) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Drosos, K.; Vogazianos, P.; Tafiadis, D.; Voniati, L.; Papanicolaou, A.; Panayidou, K.; Thodi, C. Auditory Processing and Speech Sound Disorders: Behavioral and Electrophysiological Findings. Audiol. Res. 2025, 15, 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15050119

Drosos K, Vogazianos P, Tafiadis D, Voniati L, Papanicolaou A, Panayidou K, Thodi C. Auditory Processing and Speech Sound Disorders: Behavioral and Electrophysiological Findings. Audiology Research. 2025; 15(5):119. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15050119

Chicago/Turabian StyleDrosos, Konstantinos, Paris Vogazianos, Dionysios Tafiadis, Louiza Voniati, Alexandra Papanicolaou, Klea Panayidou, and Chryssoula Thodi. 2025. "Auditory Processing and Speech Sound Disorders: Behavioral and Electrophysiological Findings" Audiology Research 15, no. 5: 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15050119

APA StyleDrosos, K., Vogazianos, P., Tafiadis, D., Voniati, L., Papanicolaou, A., Panayidou, K., & Thodi, C. (2025). Auditory Processing and Speech Sound Disorders: Behavioral and Electrophysiological Findings. Audiology Research, 15(5), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15050119