Tinnitus Prevalence, Associated Characteristics, and Treatment Patterns among Adults in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of Questionnaire

2.2. The Pilot Questionnaire

2.3. The Main Questionnaire

2.4. Participants

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Tinnitus and Associated Factors

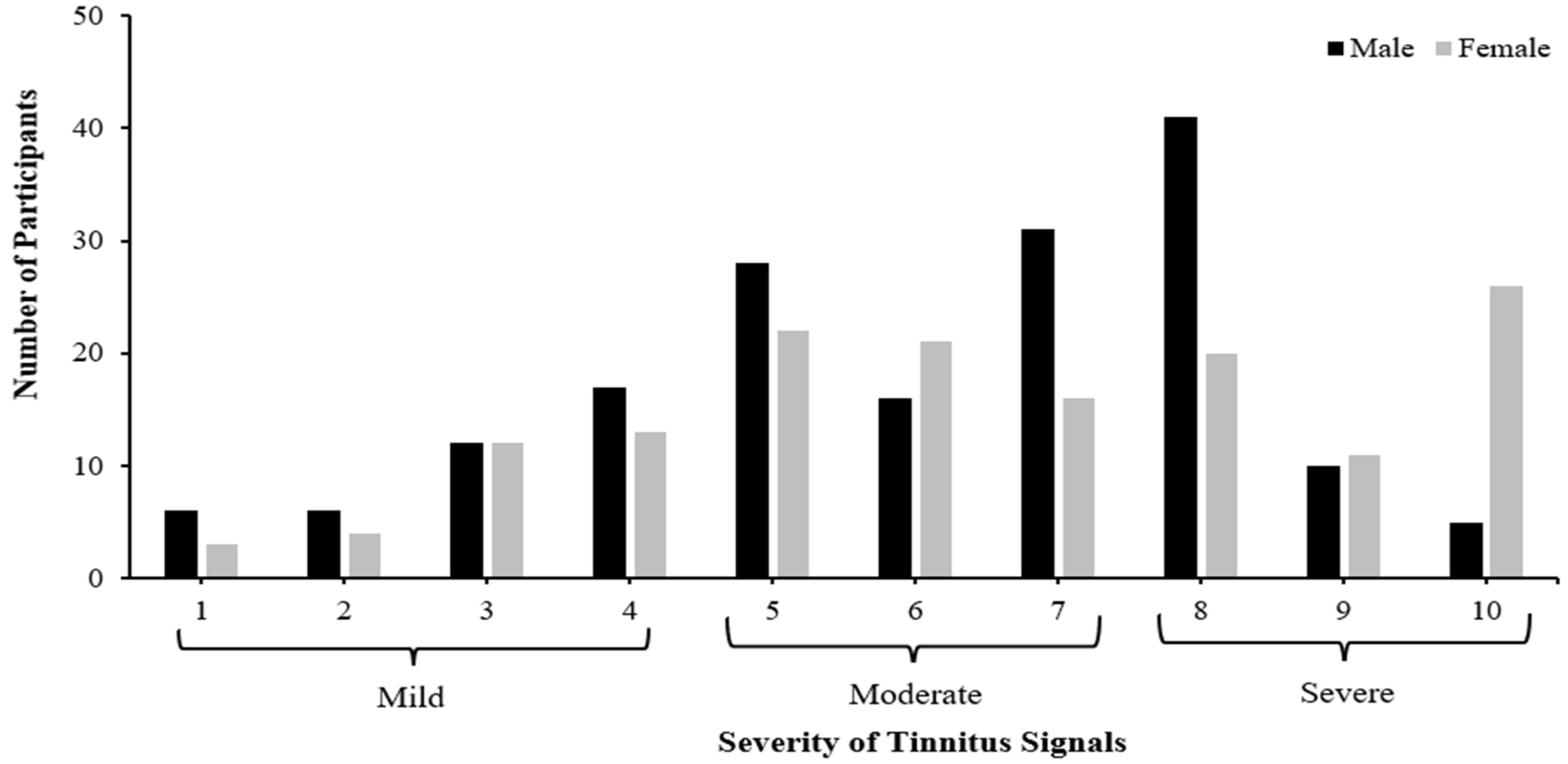

3.2. Experience of Tinnitus

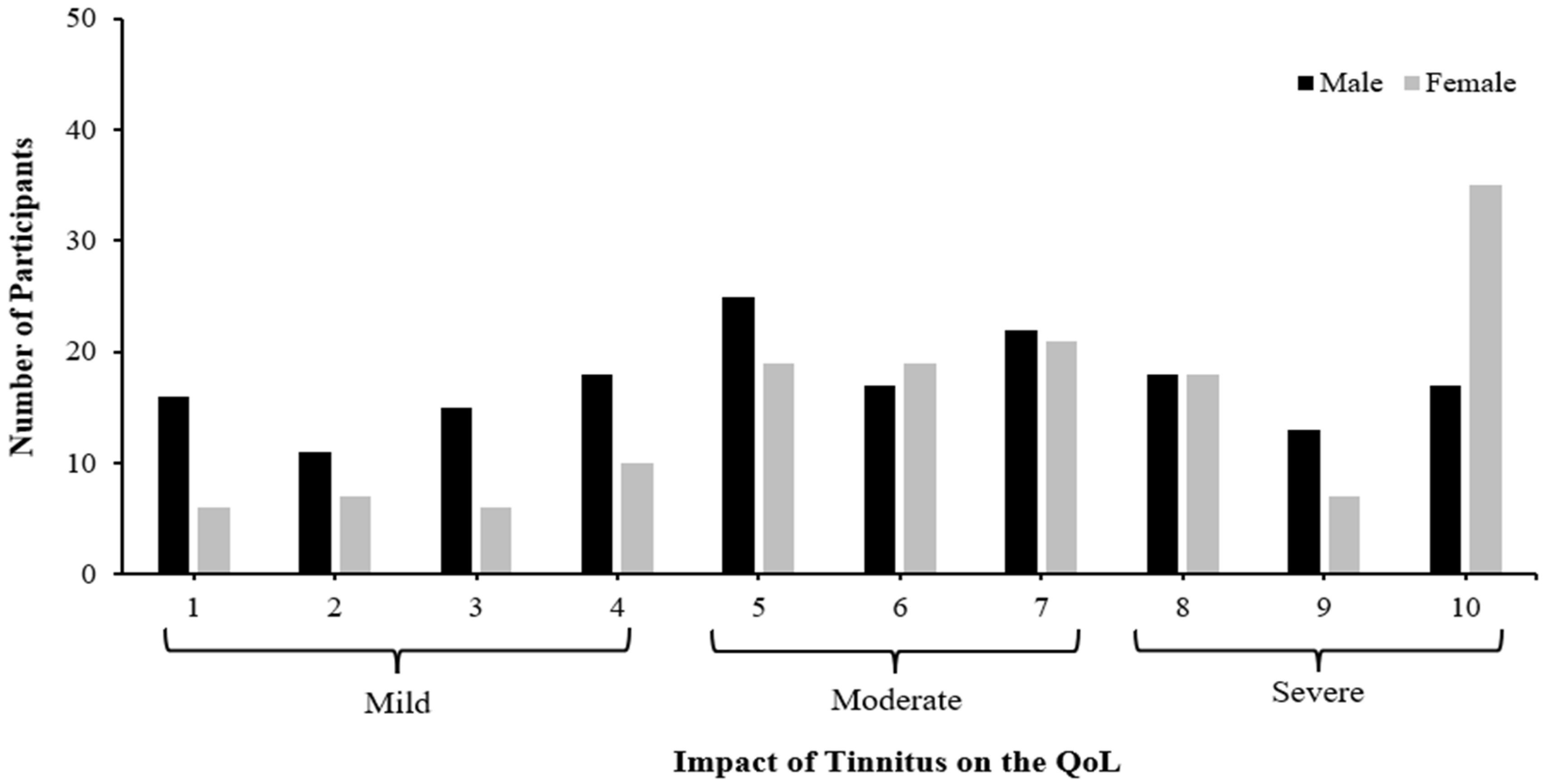

3.3. Impact of Tinnitus

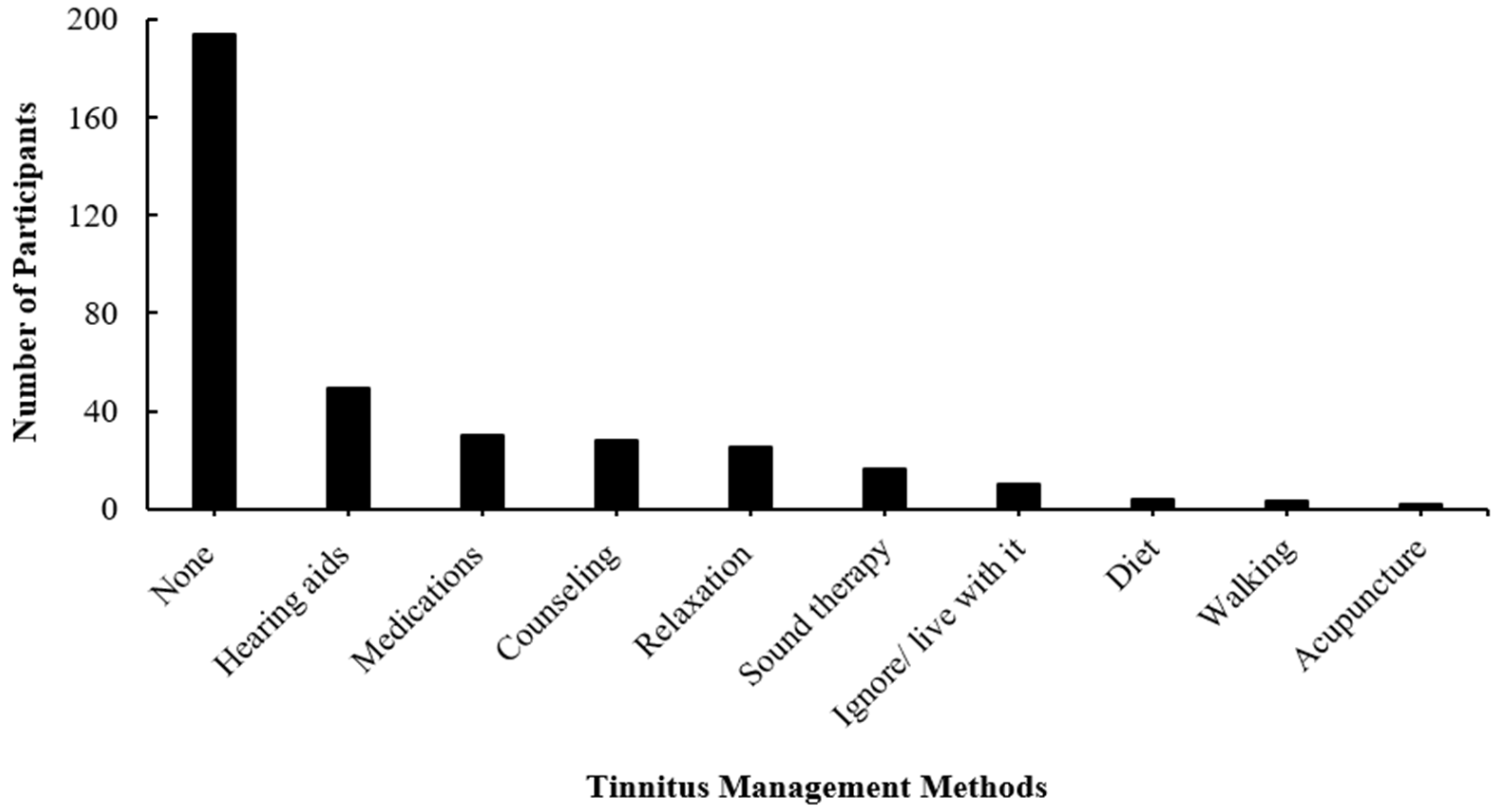

3.4. Management of Tinnitus

3.5. Association between the Impact of Tinnitus and Other Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence of Tinnitus and Associated Factors

4.2. Experience of Tinnitus

4.3. Impact of Tinnitus

4.4. Management of Tinnitus

5. Study Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire

- A.

- Demographics and associated factors

- 1.

- What is your gender?

- ○

- Male

- ○

- Female

- 2.

- What is your age (years)?

- ○

- 18–30

- ○

- 31–40

- ○

- 41–50

- ○

- 51–60

- ○

- 61–70

- ○

- 71–80

- ○

- 81–90

- ○

- >90

- 3.

- What is your nationality?

- ○

- Saudi

- ○

- Non-Saudi

- 4.

- Do you have hearing loss based on a hearing test conducted by an audiologist?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- 5.

- Do you wear a hearing aid/s?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- 6.

- Does your reaction to any sound (sound tolerance) similar to people around you?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No (please specify)

- B.

- Experience of Tinnitus

- 7.

- Do you know the cause of your tinnitus?

- ○

- Yes (please specify)

- ○

- No

- 8.

- How long have you had tinnitus (years)?

- ○

- <1

- ○

- 1–2

- ○

- 3–5

- ○

- 6–8

- ○

- 9–10

- ○

- >10

- 9.

- What is the first onset of your tinnitus?

- ○

- Sudden

- ○

- Gradual

- 10.

- How do you describe the duration of your tinnitus?

- ○

- Constant

- ○

- Intermittent

- 11.

- What is the number of times you perceive tinnitus?

- ○

- Daily

- ○

- Weekly

- ○

- Monthly

- ○

- Sometimes

- ○

- Other (please specify)

- 12.

- What is the sound of your tinnitus? (Choose all applicable)

- ○

- Pulsing

- ○

- Ringing

- ○

- Whooshing

- ○

- Whistling

- ○

- Buzzing

- ○

- Clicking

- ○

- Other (please specify)

- 13.

- Where do perceive your tinnitus? (Choose all applicable)

- ○

- Right Ear

- ○

- Left Ear

- ○

- Both Ears

- ○

- Head

- 14.

- What is the severity of your tinnitus? (Choose from 1 to 10, [10 is very severe])

- ○

- 1

- ○

- 2

- ○

- 3

- ○

- 4

- ○

- 5

- ○

- 6

- ○

- 7

- ○

- 8

- ○

- 9

- ○

- 10

- C.

- Impact of Tinnitus

- 15.

- What is the impact of tinnitus on your quality of life? (Choose from 1 to 10, [10 is very severe])

- ○

- 1

- ○

- 2

- ○

- 3

- ○

- 4

- ○

- 5

- ○

- 6

- ○

- 7

- ○

- 8

- ○

- 9

- ○

- 10

- 16.

- Are you afraid that your tinnitus gets worse?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- 17.

- Does your tinnitus make you feel depressed or anxious?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- 18.

- What activities are affected by your tinnitus? (Choose all applicable)

- ○

- Concentration

- ○

- Work

- ○

- Sleep

- ○

- Social

- ○

- Sports

- ○

- Quiet settings

- ○

- Other (please specify)

- D.

- Management of Tinnitus

- 19.

- What management/treatment services and/or devices have you tried to manage your tinnitus? (Choose all applicable)

- ○

- Hearing aids

- ○

- Sound therapy

- ○

- Medical Counseling

- ○

- Medications

- ○

- Relaxation

- ○

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- ○

- Tinnitus Retraining Therapy

- ○

- Other (please specify)

- ○

- Nothing

- 20.

- Are you satisfied with the method you have been using to relieve your tinnitus?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- ○

- Not applicable

- 21.

- Would you like to receive more information about tinnitus?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

References

- Kajuter, J.; Schaap, G.; Sools, A.; Simões, J.P. Using participatory action research to redirect tinnitus treatment and research—An interview study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.I.; Lee, H.W.; Ryu, S.; Kim, J.S. Tinnitus update. J. Clin. Neurol. 2021, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langguth, B.; Kreuzer, P.M.; Kleinjung, T.; De Ridder, D. Tinnitus: Causes and clinical management. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.S.; Koo, M.; Chen, J.C.; Hwang, J.H. The association between tinnitus and the risk of ischemic cerebrovascular disease in young and middle-aged patients: A secondary case-control analysis of a nationwide, population-based health claims database. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nondahl, D.M.; Cruikshanks, K.J.; Wiley, T.L.; Klein, B.E.K.; Klein, R.; Chapell, R.; Tweed, T.S. The ten-year incidence of tinnitus among older adults. Int. J. Audiol. 2010, 49, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.H.; Han, K.D.; Park, K.H. Associate of hearing loss and tinnitus with health-related quality of life: The Korea national health and nutrition examination survey. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ridder, D.; Schlee, W.; Vanneste, S.; Londero, A.; Weisz, N.; Kleinjung, T.; Shekhawat, G.S.; Elgoyhen, A.B.; Song, J.-J.; Andersson, G.; et al. Tinnitus and tinnitus disorder: Theoretical and operational definitions (an international multidisciplinary proposal). Prog. Brain. Res. 2021, 260, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamad, N.; Hoare, D.J.; Hall, D.A. The consequences of tinnitus and tinnitus severity on cognition: A review of the behavioral evidence. Hear. Res. 2016, 322, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, K.E.B.; Corrêa, C.C.; Gonçalves, C.G.O.; Baran, J.B.C.; Marques, J.M.; Zeigelboim, B.S.; José, M.R. Effect of tinnitus on sleep quality and insomnia. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2023, 27, e197–e202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFerran, D.J.; Stockdale, D.; Holme, R.; Large, C.H.; Baguley, D.M. Why is there no cure for tinnitus? Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunkel, D.E.; Bauer, C.A.; Sun, G.H.; Rosenfeld, R.M.; Chandrasekhar, S.S.; Cunningham, E.R., Jr.; Archer, S.M.; Blakley, B.W.; Carter, J.M.; Granieri, E.C.; et al. Clinical practice guideline: Tinnitus. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2014, 151 (Suppl. S2), S1–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademaker, M.M.; Meijers, S.M.; Smit, A.L.; Stegeman, I. Prediction models for tinnitus presence and the impact of tinnitus on daily life: A systematic review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, C.W.; Sandridge, S.A.; Jacobson, G.P. Psychometric adequacy of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) for evaluating treatment outcome. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 1998, 9, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Henry, J.A.; Griest, S.; Thielman, E.; McMillan, G.; Kaelin, C.; Carlson, K.F. Tinnitus functional index: Development, validation, outcomes research, and clinical application. Hear. Res. 2016, 334, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobo, P.; Cuesta, M. Special Issue “New insights into pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of tinnitus”. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atik, A. Pathophysiology and treatment of tinnitus: An elusive disease. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2014, 66 (Suppl. S1), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarach, C.M.; Lugo, A.; Scala, M.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Cederroth, C.R.; Odone, A.; Garavello, W.; Schlee, W.; Langguth, B.; Gallus, S. Global prevalence and incidence of tinnitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2022, 79, 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsanosi, A.A. Impact of tinnitus on the quality of life among Saudi patients. Saudi Med. J. 2011, 32, 1274–1278. [Google Scholar]

- Musleh, A.; Alharthy, A.K.H.; Alzahrani, M.Y.M.; Bin Maadhah, S.A.; Al Zehefa, I.A.; AlQahtani, R.Y.; Alshehri, I.S.M.; Alqahtani, F.B.A.; Asiri, K.A.M.; Almushari, A.A. Psychological impact and quality of life in adults with tinnitus: A cross-sectional study. Cureus 2024, 16, e51976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nondahl, D.M.; Cruickshanks, K.J.; Wiley, T.L.; Klein, R.; Klein, B.E.; Tweed, T.S. Prevalence and 5-year incidence of tinnitus among older adults: The epidemiology of hearing loss study. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2002, 13, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.A.; Dennis, K.C.; Schechter, M.A. General review of tinnitus: Prevalence, mechanisms, effects, and management. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2005, 48, 1204–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.A.; Mehta, R.L.; Argstatter, H. Interpreting the tinnitus questionnaire (German version): What individual differences are clinically important? Int. J. Audiol. 2018, 57, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalessi, M.; Farhadi, M.; Asghari, A.; Kamrava, S.K.; Amintehran, E.; Ghalehbaghi, S.; Heshmatzadeh Behzadi, A.; Pousti, S.B. Tinnitus: An epidemiologic study in Iranian population. Acta. Med. Iran. 2013, 51, 886–891. [Google Scholar]

- Khedr, E.M.; Ahmed, M.A.; Shawky, O.A.; Mohamed, E.S.; El Attar, G.S.; Mohammad, K.A. Epidemiological study of chronic tinnitus in Assiut, Egypt. Neuroepidemiology 2010, 35, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassar, M.; Islam, M.S.; D’souza, S.; Praveen, M.; Al Masri, M.H.; Sauro, S.; Jamleh, A. Tinnitus prevalence and associated factors among dental clinicians in the United Arab Emirates. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khreesha, L.; Al-Rawashdeh, B.; Tawalbeh, M.; Sawalha, A.; Doudin, M.; Dardas, M.; Mahafda, H.; Omari, R.; Bello, Z.; Alhyari, A. Epidemiology and characteristics of tinnitus in Jordan. Int. Tinnitus J. 2024, 28, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nondahl, D.M.; Cruickshanks, K.J.; Huang, G.-H.; Klein, B.E.K.; Klein, R.; Nieto, F.J.; Tweed, T.S. Tinnitus and its risk factors in the Beaver Dam Offspring Study. Int. J. Audiol. 2011, 50, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormack, A.; Edmondson-Jones, M.; Fortnum, H.; Dawes, P.; Middleton, H.; Munro, K.J.; Moore, D.R. The prevalence of tinnitus and the relationship with neuroticism in a middle-aged UK population. J. Psychosom. Res. 2014, 76, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, T.G.; Medeiros, I.R.; Levy, C.P.; Ramalho, J.D.R.; Bento, R.F. Tinnitus in normally hearing patients: Clinical aspects and repercussions. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2005, 71, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oiticica, J.; Bittar, R.S. Tinnitus prevalence in the city of São Paulo. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 81, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, C.; Wallenhorst, C.; McFerran, D.; Hall, D.A. Incidence rates of clinically significant tinnitus: 10-year trend from a cohort study in England. Ear Hear. 2015, 36, e69–e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubak, T.; Kock, S.; Koefoed-Nielsen, B.; Lund, S.P.; Bonde, J.P.; Kolstad, H.A. The risk of tinnitus following occupational noise exposure in workers with hearing loss or normal hearing. Int. J. Audiol. 2008, 47, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kryter, K.D. Effects of nosocusis, and industrial and gun noise on hearing of U.S. adults. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1991, 90, 3196–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabrizio-Stover, E.M.; Oliver, D.L.; Burghard, A.L. Tinnitus mechanisms and the need for an objective electrophysiological tinnitus test. Hear Res. 2024, 449, 109046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ridder, D.; Vanneste, S.; Freeman, W. The Bayesian brain: Phantom percepts resolve sensory uncertainty. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 44, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaab, F.A.; Alaraifi, A.K.; Alhomaydan, W.A.; Ahmed, A.Z.; Elzubair, A.G. Hearing impairment in military personnel in Eastern Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Community Med. 2021, 28, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALqarny, M.; Assiri, A.M.; Alshehri, A.; Alharbi, S.A.; Alshahrani, E.H.; Alessa, H.; Alghubishi, S.A. Patterns and correlations of hearing loss among adolescents, adults, and elderly in Saudi Arabia: A retrospective study. Cureus 2021, 13, e13913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller, A.J. Classification and epidemiology of tinnitus. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2003, 36, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aazh, H.; McFerran, D.; Salvi, R.; Prasher, D.; Jastreboff, M.; Jastreboff, P. Insights from the first international conference on hyperacusis: Causes, evaluation, diagnosis and treatment. Noise Health 2014, 16, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederroth, C.R.; Lugo, A.; Edvall, N.K.; Lazar, A.; Lopez-Escamez, J.A.; Bulla, J.; Uhlen, I.; Hoare, D.J.; Baguley, D.M.; Canlon, B.; et al. Association between hyperacusis and tinnitus. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Seidman, M. Tinnitus in the older adult: Epidemiology, pathophysiology and treatment options. Drugs Aging. 2004, 21, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michikawa, T.; Nishiwaki, Y.; Kikuchi, Y.; Saito, H.; Mizutari, K.; Okamoto, M.; Takebayashi, T. Prevalence and factors associated with tinnitus: A community-based study of Japanese elders. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 20, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althomali, O.W.; Amin, J.; Acar, T.; Shahanawaz, S.; Alanazi, T.A.; Alnagar, D.K.; Almeshari, M.; Alzamil, Y.; Althomali, K.; Alshoweir, N.; et al. Prevalence of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in Saudi Arabia and associated modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors: A population-based cross-sectional study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciminelli, P.; Machado, S.; Palmeira, M.; Carta, M.G.; Beirith, S.C.; Nigri, M.L.; Mezzasalma, M.A.; Nardi, A.E. Tinnitus: The sound of stress? Clin Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2018, 14, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanazi, A.A. Referral and lost to system rates of two newborn hearing screening programs in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2020, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, S.; Bhatarai, P.; Prabhu, P. Awareness and experience of tinnitus in Nepalese young adult population. Ann. Otol. Neurotol. 2022, 5, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, E.; Testa, M.A.; Hartnick, C. Prevalence of noise-induced hearing-threshold shifts and hearing loss among US youths. Pediatrics 2011, 127, e39–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, B.; Xiong, Q.; Schroeder-Butterfill, E. Impact of the use of the internet on quality of life in older adults: Review of literature. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2020, 21, e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoroff, S.M.; Konrad-Martin, D. Noise: Acoustic trauma and tinnitus, the US military experience. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 53, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, B.E.; Agrup, C.; Haskard, D.O.; Luxon, L.M. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Lancet 2010, 375, 1203–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligmann, H.; Podoshin, L.; Ben-David, J.; Fradis, M.; Goldsher, M. Drug-induced tinnitus and other hearing disorders. Drug Saf. 1996, 14, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilles, A.; Van Hal, G.; De Ridder, D.; Wouters, K.; Van de Heyning, P. Epidemiology of noise-induced tinnitus and the attitudes and beliefs towards noise and hearing protection in adolescents. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sindhusake, D.; Mitchell, P.; Newall, P.; Golding, M.; Rochtchina, E.; Rubin, G. Prevalence and characteristics of tinnitus in older adults: The Blue Mountains Hearing Study. Int. J. Audiol. 2003, 42, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, S.; Padgham, N.D. “Ringing in the ears”: Narrative review of tinnitus and its impact. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2011, 13, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, E.; Behr, R.; Neumann-Haefelin, T.; Schwager, K. Pulsatile tinnitus: Imaging and differential diagnosis. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2013, 110, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narsinh, K.H.; Hui, F.; Duvvuri, M.; Meisel, K.; Amans, M.R. Management of vascular causes of pulsatile tinnitus. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2022, 14, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, N.; Katarkar, A.; Shah, P.; Jalvi, R.; Jain, A.; Shah, M. Audiological, psychological and cognitive characteristics of tinnitus sufferers. Indian J. Otolaryngol. 2012, 18, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombe, A.; Baguley, D.; Coles, R.; McKenna, L.; Mckinney, C.; Windle-Taylor, P. Guidelines for the grading of tinnitus severity: The results of a working group commissioned by the British Association of Otolaryngologists, Head and Neck Surgeons, 1999. Clin. Otolaryngol. Allied. Sci. 2001, 26, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cima, R.F.; Crombez, G.; Vlaeyen, J.W. Catastrophizing and fear of tinnitus predict quality of life in patients with chronic tinnitus. Ear Hear. 2011, 32, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackenberg, B.; Döge, J.; O’Brien, K.; Bohnert, A.; Lackner, K.J.; Beutel, M.E.; Michal, M.; Münzel, T.; Wild, P.S.; Pfeiffer, N.; et al. Tinnitus and its relation to depression, anxiety, and stress: A population-based cohort study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folmer, R.L.; Griest, S.E.; Martin, W.H. Chronic tinnitus as phantom auditory pain. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2001, 124, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, G. Psychological aspects of tinnitus and the application of cognitive-behavioral therapy. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2002, 22, 977–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, A.H.; Salvi, R.J.; Burkard, R.F. Tinnitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlandsson, S.I.; Hallberg, L.R.; Axelsson, A. Psychological and audiological correlates of perceived tinnitus severity. Audiol. 1992, 31, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiller, W.; Goebel, G. Factors influencing tinnitus loudness and annoyance. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2006, 132, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nondahl, D.M.; Cruickshanks, K.J.; Dalton, D.S.; Klein, B.E.; Klein, R.; Schubert, C.R.; Tweed, T.S.; Wiley, T.L. The impact of tinnitus on quality of life in older adults. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2007, 18, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meric, C.; Gartner, M.; Collet, L.; Chéry-Croze, S. Psychopathological profile of tinnitus sufferers: Evidence concerning the relationship between tinnitus features and impact on life. Audiol. Neurotol. 1998, 3, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.A. Directed attention and habituation: Two concepts critical to tinnitus management. Am. J. Audiol. 2023, 32, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.J.; Chen, K. The relationship of tinnitus, hyperacusis, and hearing loss. Ear. Nose. Throat. J. 2004, 83, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, F.G. Tinnitus and hyperacusis: Central noise, gain and variance. Curr Opin Physiol. 2020, 18, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastreboff, P.J.; Jastreboff, M.M. Tinnitus retraining therapy for patients with tinnitus and decreased sound tolerance. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2003, 36, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sindhusake, D.; Golding, M.; Wigney, D.; Newall, P.; Jakobsen, K.; Mitchell, P. Factors predicting severity of tinnitus: A population-based assessment. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2004, 15, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisz, N.; Voss, S.; Berg, P.; Elbert, T. Abnormal auditory mismatch response in tinnitus sufferers with high-frequency hearing loss is associated with subjective distress level. BMC. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, D.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, S.K.; Kang, H.J.; Yeo, S.G. Review of pharmacotherapy for tinnitus. Healthcare 2021, 9, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, V.; Cooke, B.; Eitutis, S.; Simpson, M.T.W.; Beyea, J.A. Approach to tinnitus management. Can. Fam. Physician. 2018, 64, 491–495. [Google Scholar]

- Bagwandin, V.; Joseph, L. A survey exploring awareness and experience of tinnitus in young adults. S. Afr. J. Commun. Disord. 2017, 64, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.A.; McMillan, G.; Dann, S.; Bennett, K.; Griest, S.; Theodoroff, S.; Silverman, S.P.; Whichard, S.; Saunders, G. Tinnitus Management: Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Extended-Wear Hearing Aids, Conventional Hearing Aids, and Combination Instruments. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2017, 28, 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boecking, B.; Psatha, S.; Nyamaa, A.; Dettling-Papargyris, J.; Funk, C.; Oppel, K.; Brueggemann, P.; Rose, M.; Mazurek, B. Hearing aid use time is causally influenced by psychological parameters in mildly distressed patients with chronic tinnitus and mild-to-moderate hearing loss. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, J.; Waddell, A. Tinnitus. BMJ. Clin. Evid. 2014, 2014, 0506. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, R.S.; Chang, S.A.; Gehringer, A.; Gogel, S. Tinnitus: How you can help yourself. J. Audiol. Med. 2008, 6, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.A.; Zaugg, T.L.; Myers, P.J.; Kendall, C.J.; Michaelides, E.M. A triage guide for tinnitus. J. Fam. Pract. 2010, 59, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.; Verrier, E.; Walsh, M.; Lind, C. Adults’ perceptions of their tinnitus and a tinnitus information service. Aust. N. Z. J. Audiol. 2012, 32, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Alanazi, A.A. Audiology and speech-language pathology practice in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Health. Sci. 2017, 11, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Matti, A.I.; McCarl, H.; Klaer, P.; Keane, M.C.; Chen, C.S. Multiple sclerosis: Patients’ information sources and needs on disease symptoms and management. Patient. Prefer. Adherence 2010, 4, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepu, R.; Rasheed, A.; Nagavi, B. Effect of patient counselling on quality of life in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in two selected south Indian community pharmacies. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2007, 69, 519–524. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Total (n = 320) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | |||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 172 (53.8) | ||

| Female | 148 (46.2) | ||

| Age (years) | Male | Female | Total |

| 18–30 | 13 (7.5) | 14 (9.5) | 27 (8.4) |

| 31–40 | 12 (7.0) | 11 (7.4) | 23 (7.2) |

| 41–50 | 23 (13.4) | 14 (9.5) | 37 (11.6) |

| 51–60 | 39 (22.7) | 34 (23.0) | 73 (22.8) |

| 61–70 | 50 (29.1) | 43 (29.0) | 93 (29.1) |

| 71–80 | 31 (18.0) | 29 (19.6) | 60 (18.7) |

| 81–90 | 4 (2.3) | 3 (2.0) | 7 (2.2) |

| >90 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Nationality | |||

| Saudi | 316 (98.8) | ||

| Non-Saudi | 4 (1.2) | ||

| Hearing loss | |||

| Yes | 223 (69.7) | ||

| No | 97 (30.3) | ||

| Hearing aid/s usage | |||

| Yes | 61 (19.1) | ||

| No | 259 (80.9) | ||

| Sound tolerance | |||

| Normal | 171 (53.4) | ||

| Abnormal (Hyperacusis) | 149 (46.6) | ||

| Experience of Tinnitus | Total (n = 320) |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Cause | |

| Unaware | 205 (64) |

| Aware | 116 (36) |

| Probable causes | |

| |

| Period of complaints (years) | |

| <1 | 42 (13.1) |

| 1–2 | 76 (23.8) |

| 3–5 | 58 (18.1) |

| 6–8 | 22 (6.9) |

| 9–10 | 33 (10.3) |

| >10 | 89 (27.8) |

| Onset | |

| Gradual | 169 (52.8) |

| Sudden | 151 (47.2) |

| Duration | |

| Continuous | 217 (67.8) |

| Intermittent | 103 (32.2) |

| Perception time | |

| Daily | 227 (70.9) |

| Weekly | 37 (11.6) |

| Monthly | 6 (1.9) |

| Sometimes | 50 (15.6) |

| Type * | |

| Whistling | 139 (43.4) |

| Ringing | 127 (39.7) |

| Whooshing | 87 (27.2) |

| Pulsing | 26 (8.1) |

| Buzzing | 9 (2.8) |

| Clicking | 3 (0.9) |

| Location * | |

| Both ears | 166 (51.9) |

| Left ear | 74 (23.1) |

| Right ear | 60 (18.8) |

| Head | 46 (14.4) |

| Variables | Impact of Tinnitus on the QoL (n = 320) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild Impact * n (%) | Moderate Impact * n (%) | Severe Impact * n (%) | p-Value + (Chi-Square Test) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 60 (67.4) | 64 (52) | 48 (44.4) | 0.005 |

| Female | 29 (32.6) | 59 (48) | 60 (55.6) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–30 | 27 (22.0) | 0 | 0 | 0.001 |

| 31–40 | 23 (18.7) | 0 | 0 | |

| 41–50 | 36 (29.3) | 0 | 0 | |

| 51–60 | 37 (30.0) | 36 (40.4) | 0 | |

| 61–70 | 0 | 53 (59.6) | 41 (38.0) | |

| >70 | 0 | 0 | 67 (62.0) | |

| Period of complaints (years) | ||||

| <1 | 42 (34.2) | 0 | 0 | 0.001 |

| 1–2 | 0 | 28 (31.5) | 48 (44.4) | |

| 3–5 | 41 (33.3) | 0 | 17 (15.8) | |

| 6–8 | 22 (17.9) | 0 | 0 | |

| 9–10 | 1 (0.8) | 32 (35.9) | 0 | |

| >10 | 17 (13.8) | 29 (32.6) | 43 (39.8) | |

| Severity of tinnitus signals | ||||

| Mild | 73 (59.3) | 0 | 0 | 0.001 |

| Moderate | 50 (40.7) | 81 (91.0) | 3 (2.8) | |

| Severe | 0 | 8 (9.0) | 105 (97.2) | |

| Hearing loss | ||||

| Yes | 123 (100) | 40 (44.9) | 60 (55.6) | 0.001 |

| No | 0 | 49 (55.1) | 48 (44.4) | |

| Hyperacusis | ||||

| Yes | 57 (35) | 29 (42) | 63 (71.6) | 0.001 |

| No | 106 (65) | 40 (58) | 25 (28.4) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alanazi, A.A. Tinnitus Prevalence, Associated Characteristics, and Treatment Patterns among Adults in Saudi Arabia. Audiol. Res. 2024, 14, 760-777. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres14050064

Alanazi AA. Tinnitus Prevalence, Associated Characteristics, and Treatment Patterns among Adults in Saudi Arabia. Audiology Research. 2024; 14(5):760-777. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres14050064

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlanazi, Ahmad A. 2024. "Tinnitus Prevalence, Associated Characteristics, and Treatment Patterns among Adults in Saudi Arabia" Audiology Research 14, no. 5: 760-777. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres14050064

APA StyleAlanazi, A. A. (2024). Tinnitus Prevalence, Associated Characteristics, and Treatment Patterns among Adults in Saudi Arabia. Audiology Research, 14(5), 760-777. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres14050064