Abstract

Background: Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (ACP) is a life-threatening, rare condition of non-mechanical colon dilatation that can result in bowel ischaemia and perforation. The aetiology is relatively unknown but includes older age coupled with high comorbidity, decreased parasympathetic activity, certain medications, chemoradiotherapy and recent surgery. There are limited research data on ACP following reversal of ileostomy after ultra-low anterior resections (ULAR), thus this systematic review included cases from various types of bowel surgeries. Methods: A comprehensive literature search of relevant articles was conducted using the EMBASE, Medline, PubMed, Cochrane, and Scopus databases. Two cases of ACP following ileostomy reversal after ULAR for rectal cancer were also reported from the authors’ rural institution. This systematic review was conducted according to PRISMA 2020 guidelines. Results: A total of 522 studies were screened of which five case reports were included. Two case series (six patients) and the two patients from the authors’ rural institution developed ACP following reversal of ileostomy post-ULAR with potential causes being the > 6 months’ time from initial surgery to reversal causing prolonged colonic mucosal inflammation and reduced wall contractile strength. Anastomotic leak and chemoradiotherapy were other considerations. One of the rural patients developed right colon ischaemia and perforation needing urgent laparotomy, right hemicolectomy and formation of end ileostomy and mucous fistula. Conservative treatment included aperients, enemas, flatus tube, bedside or endoscopic decompression, and neostigmine. Conclusions: Early recognition is vital to treat ACP with medical therapy and decompression to prevent bowel ischaemia and perforation. Further research is needed to better characterise the aetiology, incidence and management strategies for this rare condition.

1. Introduction

ACP (Ogilvie Syndrome) is the abnormal dilation of the large bowel from the caecum to the splenic flexure, in the absence of mechanical obstruction [1]. The exact aetiology of ACP remains unclear, but it is predominantly observed in Western populations, particularly among elderly patients (>80 years old) with multiple co-morbidities [2]. Other possible causes include the inhibition of parasympathetic activity from the sacral plexus, decreased splanchnic perfusion, anticholinergic medications, recent surgery, opiates, and electrolyte disturbances particularly hypokalaemia [1]. The main concern with colonic pseudo-obstruction is the bowel dilation which can lead to ischaemia and perforation [3].

Reversal of ileostomy is considered a relatively minor surgical procedure but has been associated with significant morbidity including intestinal obstruction, fistulas, anastomotic leaks, and symptoms of low anterior resection syndrome [4]. However, ACP is a very rare complication following this procedure and any bowel surgery in general [3]. We have focused on this complication following reversal of ileostomy because in particular as it is an extremely rare event (two case reports world-wide), yet has occurred twice in our rural institution. An extensive literature search demonstrated only two case reports demonstrating this pathology following closure of loop ileostomy and three case reports describing other types of bowel surgery [5,6,7,8,9].

In this systematic review and case series we present the experience of two patients who developed ACP after ileostomy reversal at our institution in rural NSW, to raise awareness about this rare condition and the need for more research into the epidemiology, incidence and outcomes of this potentially life-threatening event.

2. Methods

We performed an extensive literature search of relevant articles using the EMBASE, Medline, PubMed, Cochrane, and Scopus databases. Additional sources, including Google Scholar, were consulted to ensure comprehensive literature coverage. Keywords included Ogilvie Syndrome, pseudo-obstruction, bowel obstruction, ileostomy closure, reversal of ileostomy, bowel surgery, and surgery. The search was conducted in August 2024, looking at research published in the last 30 years. It revealed 522 articles which were filtered through relevant inclusion and exclusion criteria yielding five studies (all case reports/series) that were applicable for analysis. Authors KC and AD performed this search and results were agreed upon by all authors. All studies were thoroughly reviewed and independent verifications of inclusion and exclusion criteria were made by all authors

All research was conducted in compliance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines. This systematic review is currently not registered. Informed consent for participation was obtained from the two subjects involved in the case studies of our local institution.

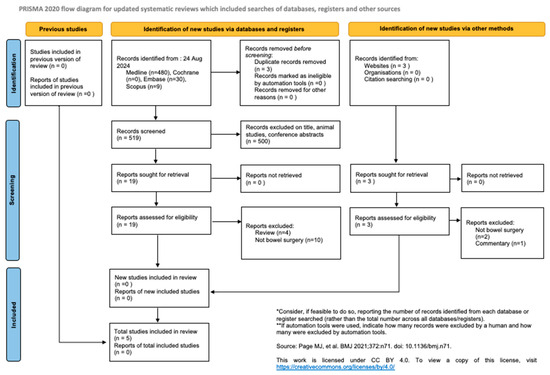

Inclusion criteria included articles written in English, and participants who underwent bowel surgery and for whom colonic pseudo-obstruction was a post-operative complication. Exclusion criteria included articles that were animal studies, conference abstracts, literature or narrative reviews, and commentaries. The outcome and conduct of the literature search are reflected in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) [10].

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram of literature and database search for this systematic review. Page MJ et al. BMJ 2021;372:n71.doic 10.1136/bmj.n71 [11].

2.1. Cases from Our Institution

2.1.1. Case 1

A 68-year-old male underwent an elective reversal of loop ileostomy and adhesiolysis in the context of having a previous laparoscopic ULAR and formation of loop ileostomy the year prior for rectal adenocarcinoma. He underwent adjuvant chemotherapy for 6 months following the ULAR. His past medical history included ischaemic heart disease with previous coronary bypass graft surgery, hypertension, and COPD. He was an ex-smoker. His pre-operative work-up included a CT with rectal contrast as well as a flexible sigmoidoscopy. Neither demonstrated evidence of anastomotic leak or stenosis.

The reversal of the loop ileostomy was unremarkable and side-to-side bowel anastomosis was achieved using a TLC 75 mm stapler with 3/0 PDS trouser suture to secure the anastomosis. Post-operatively he was commenced on oral paracetamol, immediate-release tapentadol, intravenous metoclopramide 10 mg TDS and his regular medications.

He initially progressed well, was tolerating a clear fluid diet, passing flatus and opening bowels 2 days post-operatively. However, on day 3 his abdomen became more distended, abdominal X-ray demonstrated colonic pseudo-obstruction (Figure 2) and a 22Fr IDC was inserted with proctoscope into the rectum for bedside decompression. There was no access to a rigid sigmoidoscope at the time.

Figure 2.

Supine AP Abdominal X-ray demonstrating colonic pseudo-obstruction day 3 post reversal of loop ileostomy.

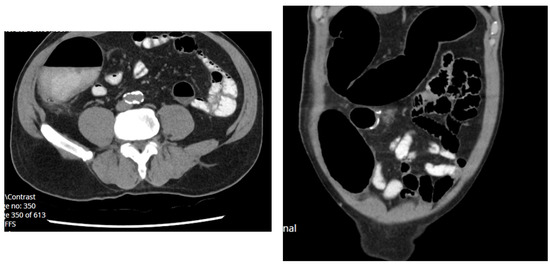

On day 4 he became febrile to 37.8 °C, had sinus tachycardia to 110 bpm and minor vomiting with worsening abdominal discomfort, seven type 7 bowel openings and was passing flatus. His blood tests revealed significantly raised inflammatory markers: WCC 16.9, CRP 180 and a new onset acute kidney injury eGFR 33, Cr 180. A CTAP with IV and oral contrast (Figure 3) demonstrated distended ascending and transverse colon with gradual transition of calibre extending towards the rectum consistent with pseudo-obstruction.

Figure 3.

Axial and coronal CT abdomen pelvis demonstrating pseudo-obstruction day 4 post reversal of loop ileostomy.

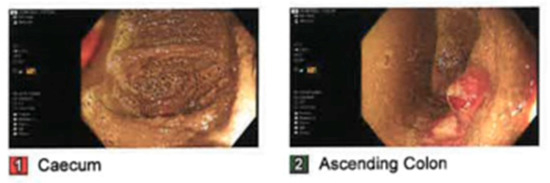

He underwent a colonoscopy the same day which demonstrated a diffuse area of erythematous mucosa in the descending, transverse, and ascending colon, as well as a caecum consistent with pressure changes and colitis from pseudo-obstruction (Figure 4). Manual decompression with colonoscope was also performed. A rectal tube was inserted. The patient received subcutaneous neostigmine 0.5 mg TDS, a clear fluid diet, IV antibiotics, intravenous fluid rehydration and an indwelling urinary catheter (IDC).

Figure 4.

Clinical photographs taken during colonoscopy of caecum and ascending colon demonstrating pressure changes and colitis from pseudo-obstruction.

Day 1 post colonoscopy he passed loose stools; the rectal tube was removed and he was commenced on a light diet. A repeat abdominal X-ray revealed a significant reduction in colonic dilatation to normal calibre and neostigmine was subsequently reduced. Stool cultures were negative, and he was commenced on regular Metamucil. His inflammatory markers also improved to WCC 8.7 and CRP 122. His renal function normalised to eGFR 88 and Cr 78. His IDC was removed day 2 post procedure and he successfully passed his trial of void. Intravenous Augmentin was transitioned to an oral course to complete 5 days total of antibiotic therapy. He was discharged day 3 post colonoscopy and day 7 post reversal of ileostomy. He did not develop further complications.

2.1.2. Case 2

A 60-year-old male underwent an elective reversal of loop ileostomy and adhesiolysis in the context of having a previous laparoscopic ULAR and formation of loop ileostomy two years prior for rectal adenocarcinoma (pT3N0). He did not undergo neoadjuvant/adjuvant therapy. His past medical history included atrial fibrillation on rivaroxaban, dyslipidaemia, and GERD. He was a heavy smoker and occasionally consumed alcohol.

There were delays to his ileostomy reversal due to poor patient compliance with follow-up. He was also diagnosed in the interim with a lung adenocarcinoma for which he underwent a wedge resection. His pre-operative work-up included a CT with rectal contrast as well as a flexible sigmoidoscopy. Again, neither demonstrated evidence of anastomotic leak or stenosis.

The reversal of loop ileostomy was unremarkable and side-to-side bowel anastomosis was achieved using a TLC 75 mm stapler with 3/0 PDS trouser suture to secure the anastomosis.

Post-operatively he was commenced on oral paracetamol, oral Endone, intravenous metoclopramide 10 mg TDS, and his regular medications except rivaroxaban.

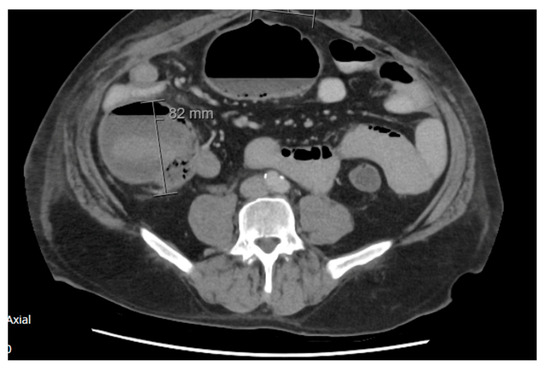

Day 1 post-operatively he passed flatus, denied nausea/vomiting and was tolerating a light diet. Day 2 post-operatively he developed worsening abdominal pain, nausea, and mild abdominal distension. His diet was de-escalated to free fluids. Day 3 post-operatively he was passing loose bowel motions, had two small vomits and a moderately distended abdomen. He developed a clinical ileus and was placed on a fast; a nasogastric tube was inserted, placed on free drainage with four hourly aspirates. There was a 1.65 L output in the first 24 h but this reduced over the next two days. On day 5 the nasogastric tube was removed and the patient commenced on a clear fluid diet, as his abdomen was less distended and he was opening his bowels multiple times. On day 6 he developed more abdominal pain. His abdomen became more distended; he was again placed on a fast and the nasogastric tube was re-inserted. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis (Figure 5) was performed the next day and revealed pseudo-obstruction. Two fleet enemas were administered, and a rectal tube was inserted then subsequently removed. He was commenced on TPN, regular lactulose 20 mg daily and 2 fleet enemas BD.

Figure 5.

Axial view of abdomen and pelvis CT scan demonstrating colonic pseudo-obstruction with caecum measuring 82 mm, day 6 post reversal of ileostomy.

The following day (day 8) he was haemodynamically stable, and feeling clinically better with reduced abdominal pain and nausea. However, an abdominal X-ray (Figure 6) revealed dilated loops of colon up to more than 9 cm and dilated loops of small bowel to 5 cm. The transverse colon was featureless and there was a suggestion of a Rigler sign (free gas) in the right upper quadrant and left lower quadrant. A subsequent abdomen and pelvis CT scan (Figure 7) revealed features of hollow viscus perforation. Several locules of gas surrounding the enteric anastomosis (within the right lower quadrant) were suspicious for an anastomotic leak. He underwent an urgent laparotomy, adhesiolysis, right hemicolectomy, formation of end ileostomy and mucous fistula. The operative findings were colonic pseudo-obstruction with the ischaemic right colon as the site of perforation, no evidence of leak at the small bowel anastomosis, a large serosal tear at the mid-transverse colon and good arterial supply to the colon, thus ischaemia was thought to have been due to pressure necrosis from pseudo-obstruction.

Figure 6.

Erect AP abdominal X-ray demonstrating Rigler sign and dilated small and large bowel loops taken day 8 post reversal of ileostomy.

Figure 7.

Axial slice of CT abdomen pelvis demonstrating pneumoperitoneum and gas locules surrounding the enteric anastomosis suspicious for leak.

Post-operatively the patient improved slowly. He was transitioned off TPN, tolerated a full diet, had a good stoma output with regular Metamucil, no abdominal pain, and was fit for discharge 3 weeks after the initial reversal of ileostomy operation. The patient underwent a reversal of the end ileostomy five months later and recovered well from this.

3. Results

Table 1 outlines the baseline characteristics, operative details, and management strategies for ACP following ileostomy reversal post-ULAR or LAR. This includes the case series by Tan et al. 2023 [5], Tominaga et al. 2019 [9], and the two cases from our rural institution. There are many similarities between our cases; of note, our patients did not undergo neoadjuvant therapy and had longer times to reversal than the other five cases primarily due to limitations with accessing timely surgeries in rural healthcare settings.

Table 1.

Summary table of reversal of ileostomy following ULAR or LAR for rectal cancer: patients’ baseline history, presenting history, management and outcomes *.

The baseline characteristics, surgical pathology, and management of subsequent pseudo-obstruction from the other three case reports outlining other bowel surgeries is demonstrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of patient demographics, operative details, management, and outcomes for studies regarding other bowel surgeries.

4. Discussion

ACP, also known as Ogilvie’s syndrome, is a rare and potentially life-threatening condition characterised by acute colonic dilatation without mechanical obstruction [1]. Common symptoms are acute abdominal distension and pain. Nausea, vomiting or constipation are not consistently present [3]. Progressive large bowel dilatation can lead to bowel ischaemia or perforation in up to 15% of cases and a high mortality rate of 40% [1]. This was evident in patient B from Tan et al., 2023 and a patient in Nakamura et al. 2024 who died following bowel perforation, and our patient 2 who had evidence of large bowel ischaemia and perforation but recovered following laparotomy [5,8].

Although the aetiology for ACP is largely unknown, it is commonly observed in hospitalised elderly patients with multiple comorbidities or severe illnesses such as cardiac or neurological events, trauma, infection, or recent surgery [2]. Possible causes of this pathology include an inhibition of parasympathetic innervation of the colon from the sacral plexus and a resultant excess of sympathetic tone [3]. This is theoretically seen following recent surgery. Medications including anticholinergics, opiates, calcium channel blockers and psychotropic agents have been associated with ACP [1].

All studies included in this systematic review, including our institution case studies, had participants that had undergone recent bowel surgeries. Our participants also took oral opioids which may have contributed to the pathology. Patients in Tan et al. 2023, and Tominaga et al. 2019, as well as our participants underwent laparoscopic ULAR for rectal cancers prior to reversal of ileostomy [5,9]. Pelvic dissection in these operations frequently results in neural injury and some studies have hypothesized that abnormal neural regeneration can contribute to colonic dysmotility [12]. In addition, the ascending fibres of the pelvic plexus and descending fibres of the inferior mesenteric plexus are sacrificed during the transection of the descending colon and inferior mesenteric artery [13]. The neorectum wall is also thinner with reduced contractile strength compared to a normal colonic wall [14].

Furthermore, the effects of forming an end ileostomy and diverting stool can result in delayed muscular inactivity of the pelvic floor, sphincter complex and affected remaining colon [12]. Thus, the risk of delayed colonic motility increases with prolonged disuse. It is recommended that reversals are undertaken 6 months after initial ULAR [15]. The patient in Tominaga et al. 2019, and four of five patients in Tan et al. 2023 underwent reversal ileostomy at 7–12 months due to the need for neoadjuvant chemoradiation [5,9]. In our cases, both patients underwent their reversals at 12–24 months due to delays with access associated with the rural healthcare system. Of note, patient 2 who had the longest delay at 24 months after initial ULAR had a worse outcome after pseudo-obstruction was identified, resulting in bowel perforation and laparotomy.

Prolonged faecal diversion also induces a risk of chronic inflammation to the affected colon [13]. In Tan et al. 2023 patients C and D underwent colonoscopy with evident erythematous mucosa and inflammation although biopsies only demonstrated regenerative changes without inflammation [5]. In our patient 1, colonoscopy revealed diffuse erythematous mucosa of the whole colon and caecum consistent with dilation pressure changes from pseudo-obstruction. No biopsies were taken. The patient in Tominaga et al. 2019 had colitis megacolon following ileostomy reversal post ULAR, and histology revealed isolated hypoganglionosis secondary to acquired isolated hypoganglionosis (AIHG) [9]. This is a very rare condition and its aetiology is unknown [16]. It can be postulated that damaged and reduced ganglion cells within Auerbach’s plexus due to ongoing colitis, can result in dysmotility causing pseudo-obstruction [16].

Tan et al. 2023 demonstrated that pre-operative radiotherapy may be a contributing factor to pseudo-obstruction of their cases due to the effects of fibrosis, possible neo-rectal hypersensitivity and subsequent impaired afferent nerve function [5]. Studies have demonstrated impaired bowel function with manometry studies post-radiotherapy [17]. None of our patients received neoadjuvant therapy. Chemotherapy including 5-fluorouracil or oxaliplatin can cause gastrointestinal dysfunction as a result of direct epithelial injury, tissue ischaemia, villi shortening and bacterial translocation [18]. Our patient 2 received adjuvant chemotherapy, four of five patients in Tan et al. 2023 and the one patient in Tominaga et al. 2019 received neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy [5,9].

Anastomotic leaks causing pelvic sepsis and inflammation could lead to pseudo-obstruction due to worsening fibrosis and decreased neorectum compliance [19]. Our patients did not have anastomotic complications however four of the five patients in Tan et al. 2023, the case of Tominaga et al. 2019, and Nakamura et al. 2024 all had anastomotic breakdowns ranging from a small sinus to a leak with collection and overt perforation [5,8,9].

Furthermore, in our case reports, patients underwent ULAR and consequent ligation at the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery which resulted in the marginal artery providing majority of blood supply to the anastomosis. Given the advanced age and comorbidities of case report subjects there is a risk of non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia primarily due to low cardiac output [20].

Management of colonic pseudo-obstruction includes medical therapy with prokinetics aperients and enemas and bedside decompression with a flatus tube [1]. Failing conservative measures, decompressive colonoscopy and neostigmine are recommended options [2]. One study suggested that decompressive colonoscopy as a first approach was associated with fever, compared with subsequent interventions using neostigmine initially [21]. In our patient 1 we pursued all medical therapy bedside, with subsequent endoscopic decompression with a flatus tube, following which neostigmine was commenced, all to good effect.

A limitations of this study was that all included research were only case reports with small sample sizes. Further research directions would be the investigation of preventative strategies and the timing of ileostomy reversal to avoid pseudo-obstruction as a complication. This should also ideally involve a larger sample size in a multi-institutional setting.

5. Conclusions

ACP after ileostomy closure in patients who have undergone ULAR for rectal cancer, and any bowel surgery in general, is a very rare but potentially life-threatening condition. Many potential causes include chemoradiotherapy, anastomotic leaks, opioid use, or neural disruption from surgery or ongoing colitis. Early recognition is vital to treat colon dilatation; this includes awareness of post-operative abdominal distension and pain, and early investigation with CT scans. Treatment includes medical therapy, bedside decompression, or endoscopic methods to prevent bowel ischaemia and perforation. Evidently, more research is required to better characterise the aetiology, incidence and management of this rare condition.

Author Contributions

K.R.C., A.D. and A.D.R. were all involved with conceptualisation, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources and data curation. K.R.C. was involved with writing—original draft preparation. K.R.C., A.D. and A.D.R. were involved with writing—review and editing and visualization. A.D.R. was involved with supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wells, C.I.; O’Grady, G.; Bissett, I.P. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction: A systematic review of aetiology and mechanisms. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 5634–5644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vanek, V.W.; Al-Salti, M. Acute pseudo-obstruction of the colon (Ogilvie’s syndrome). An analysis of 400 cases. Dis. Colon Rectum 1986, 29, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maloney, N.; Vargas, H.D. Acute intestinal pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome). Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 2005, 18, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sharma, A.; Deeb, A.P.; Rickles, A.S.; Iannuzzi, J.C.; Monson, J.R.; Fleming, F.J. Closure of defunctioning loop ileostomy is associated with considerable morbidity. Colorectal Dis. 2013, 15, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, M.N.A.; Tham, H.Y.; How, K.Y.; Wong, K.Y. Colonic pseudo-obstruction following closure of loop ileostomy after ultralow rectal resections: Five Case reports. Clin. Case Stud. Rep. 2023, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gortani, G.; Pederiva, F.; Ammar, L.; Miorin, E.; Tonin, G.; Dobbiani, G.; Marcuzzi, E.; Barbi, E. Ogilvie syndrome in a 8 year old girl after laparoscopic appendectomy. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nakamura, T.; Sugimoto, R.; Harada, S.; Nobori, S.; Ushigome, H.; Yoshikawa, M. Hand-Assisted Laparoscopic Subtotal Colectomy for Ogilvie Syndrome Associated With Idiopathic Fibrosis of Colon After Simultaneous Pancreas Kidney Transplant. Exp. Clin. Transplant. 2021, 19, 1348–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Sakuraba, S.; Koido, K.; Hazama, H.; Ohata, K. A Case of Acute Colonic Pseudo-Obstruction and Anastomotic Leakage After Sigmoidectomy for Sigmoid Volvulus. Cureus 2024, 16, e61133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tominaga, T.; Nagayama, S.; Takamatsu, M.; Miyanari, S.; Nagasaki, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Akiyoshi, T.; Konishi, T.; Fujimoto, Y.; Fukunaga, Y.; et al. A case of severe megacolon due to acquired isolated hypoganglionosis after low anterior resection for lower rectal cancer. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 13, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.F.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.Y.; Yang, S.Y.; Han, Y.D.; Cho, M.S.; Hur, H.; Min, B.S.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, N.K. Predictive Factors for Bowel Dysfunction After Sphincter-Preserving Surgery for Rectal Cancer: A Single-Center Cross-sectional Study. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2019, 62, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iizuka, I.; Koda, K.; Seike, K.; Shimizu, K.; Takami, Y.; Fukuda, H.; Tsuchida, D.; Oda, K.; Takiguchi, N.; Miyazaki, M. Defecatory malfunction caused by motility disorder of the neorectum after anterior resection for rectal cancer. Am. J. Surg. 2004, 188, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, C.; Oh, S.Y.; Choi, S.J.; Suh, K.W. Ultralow Anterior Resection and Coloanal Anastomosis for Low-Lying Rectal Cancer: An Appraisal Based on Bowel Function. Dig. Surg. 2019, 36, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowakowski, M.M.; Rubinkiewicz, M.; Gajewska, N.; Torbicz, G.; Wysocki, M.; Małczak, P.; Major, P.; Wierdak, M.; Budzyński, A.; Pędziwiatr, M. Defunctioning ileostomy and mechanical bowel preparation may contribute to development of low anterior resection syndrome. Wideochir. Inne Tech. Maloinwazyjne 2018, 13, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dingemann, J.; Puri, P. Isolated hypoganglionosis: Systematic review of a rare intestinal innervation defect. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2010, 26, 1111–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ihnát, P.; Slívová, I.; Tulinsky, L.; Ihnát Rudinská, L.; Máca, J.; Penka, I. Anorectal dysfunction after laparoscopic low anterior rectal resection for rectal cancer with and without radiotherapy (manometry study). J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 117, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boussios, S.; Pentheroudakis, G.; Katsanos, K.; Pavlidis, N. Systemic treatment-induced gastrointestinal toxicity: Incidence, clinical presentation and management. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2012, 25, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bittorf, B.; Stadelmaier, U.; Merkel, S.; Hohenberger, W.; Matzel, K.E. Does anastomotic leakage affect functional outcome after rectal resection for cancer? Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2003, 387, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagnacci, G.; Guerrini, S.; Gentili, F.; Sordi, A.; Mazzei, F.G.; Pozzessere, C.; Guazzi, G.; Mura, G.; Savelli, V.; D’Amico, S.; et al. Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) and prognostic signs at CT: Reperfusion or not reperfusion that is the question! Abdom. Radiol. 2022, 47, 1603–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, S.; Muller, A.; Butts, C.A.; Geng, T.A.; Ong, A.W. Acute Colonic Pseudo-obstruction: Colonoscopy Versus Neostigmine First? J. Surg. Res. 2023, 288, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).