Acquired Hypolipoproteinemia and Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis: A Case Series and Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Case Series

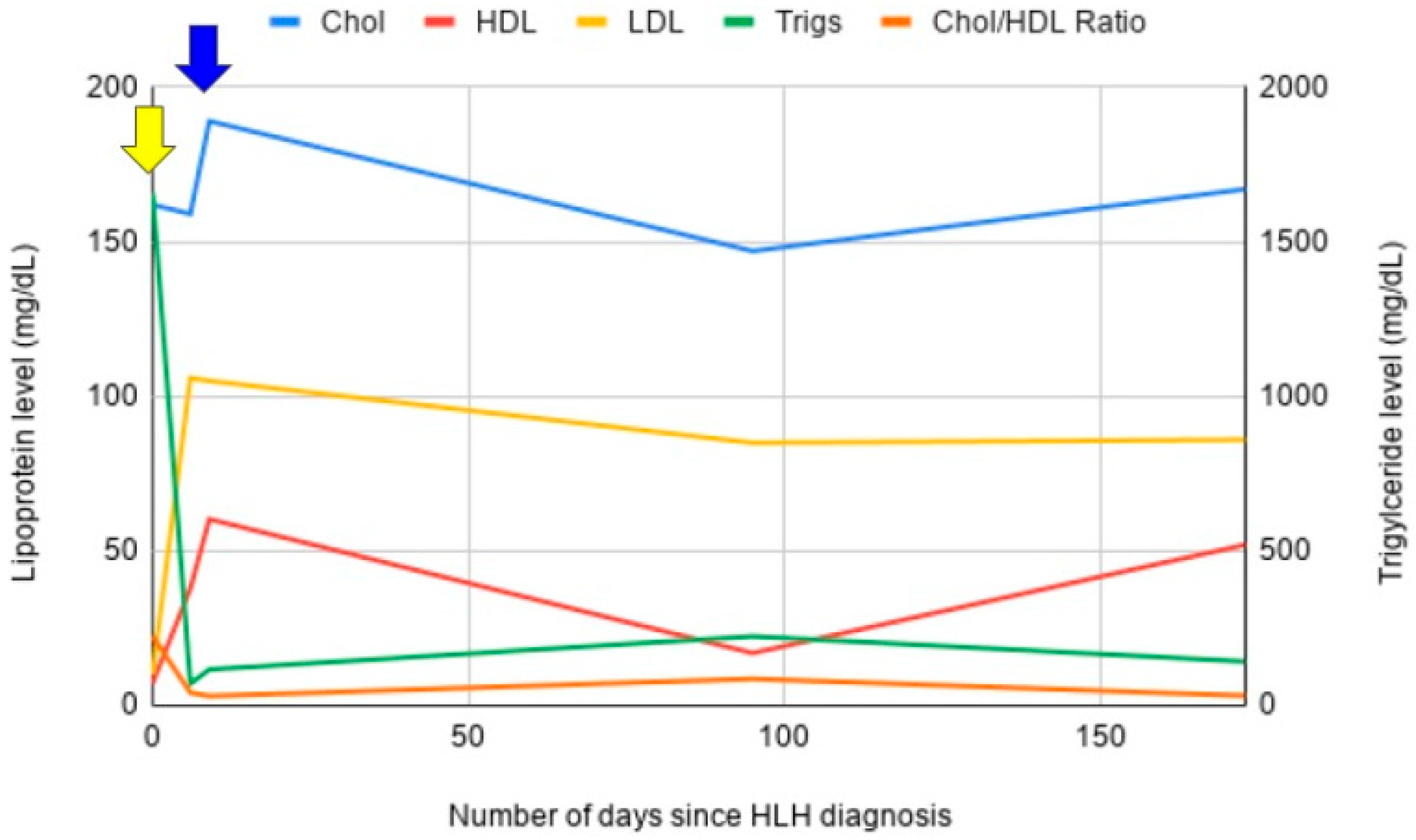

3.1. Case 1

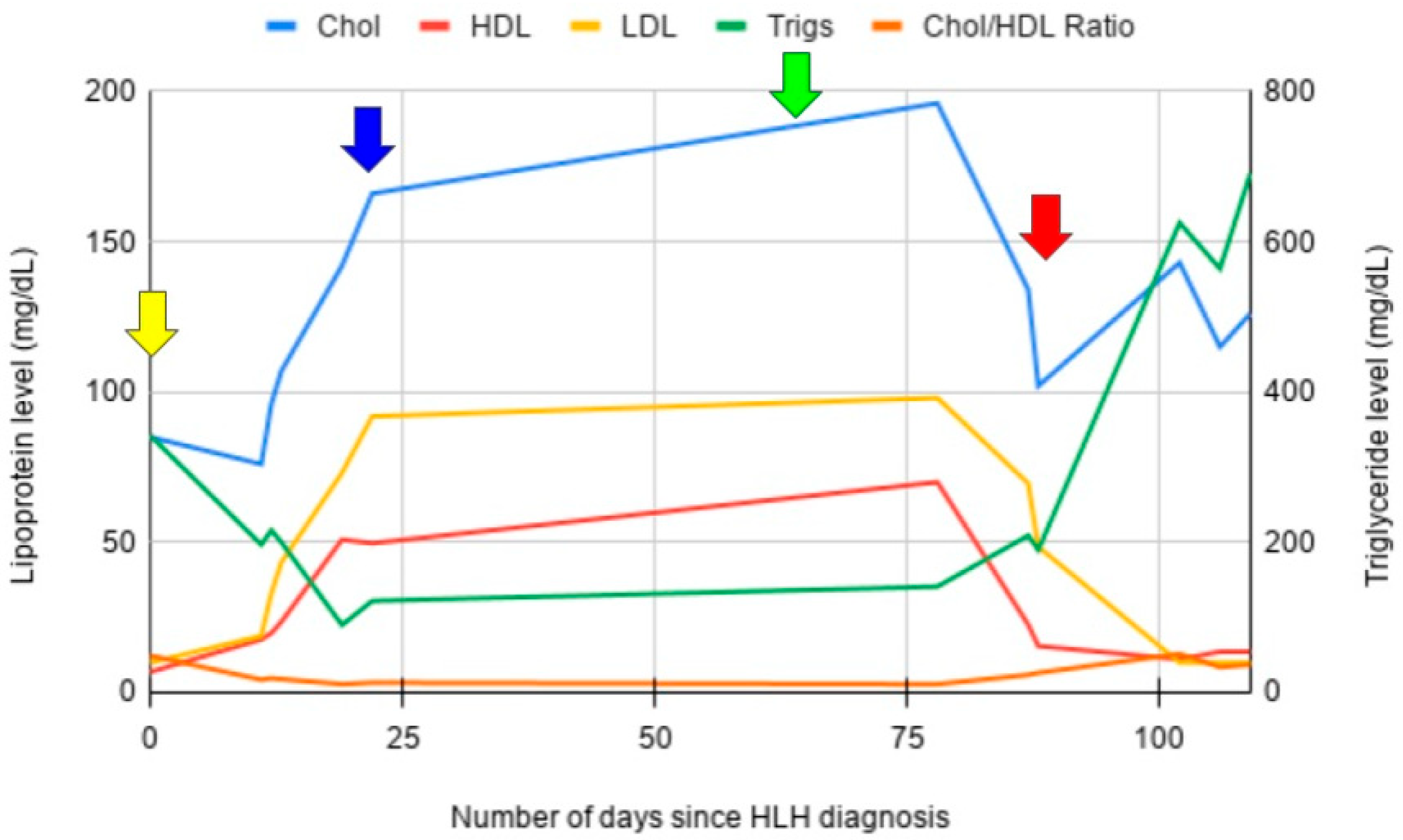

3.2. Case 2

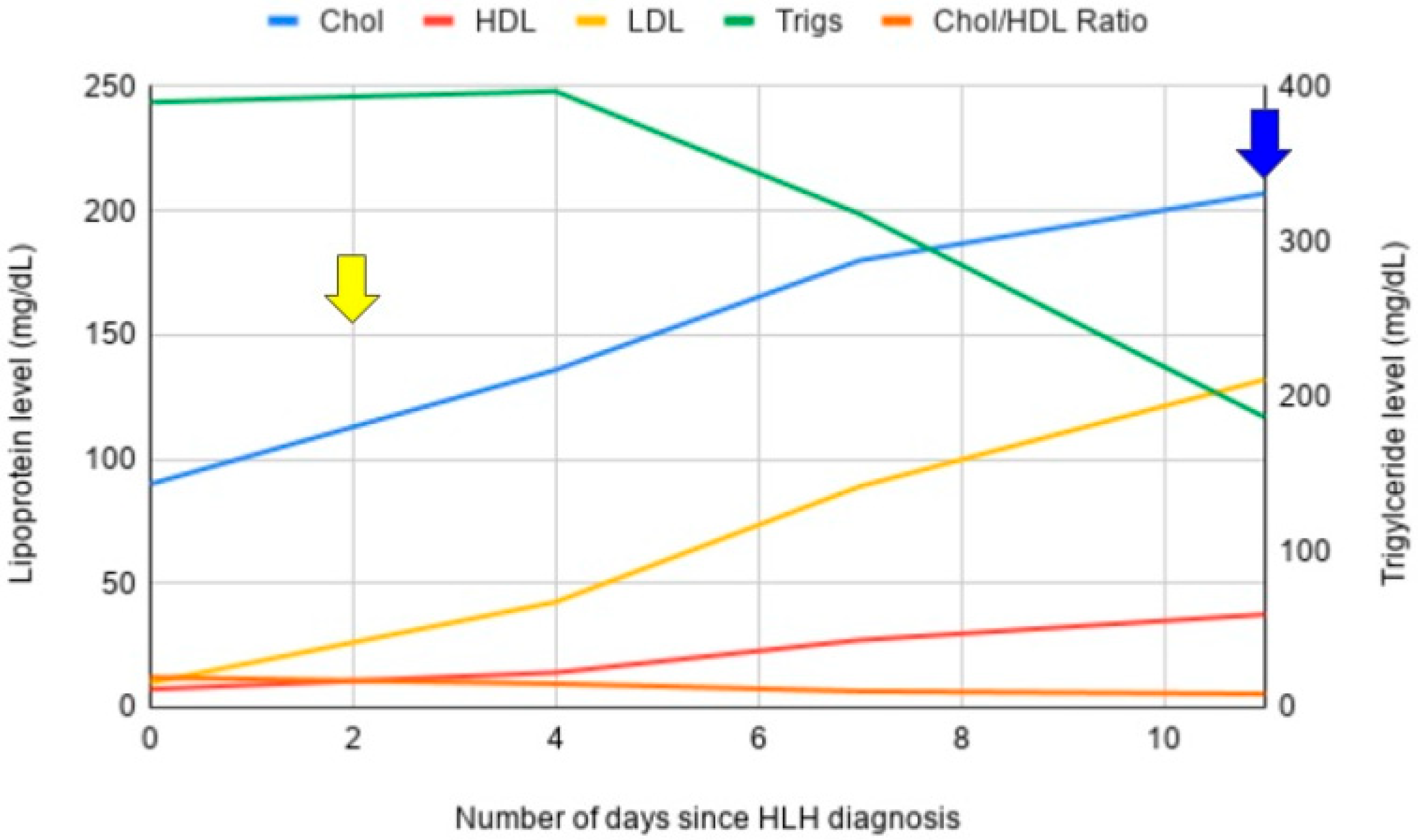

3.3. Case 3

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein |

| LDL-C | Low-density lipoprotein |

| VLDL-C | Very-low density lipoprotein |

| ERCP | Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography |

| CRRT | Continuous renal replacement therapy |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| RBC | Red blood cell |

| HLH | Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis |

| NK-cell | Natural killer cell |

| CD-47 | Cluster of differentiation 47 |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IFN-y | Interferon gamma |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| LOX-1 | Lectin-like oxidized LDL-C receptor |

| STAT | Signal transducer and activator of transcription |

References

- La Rosée, P.; Horne, A.; Hines, M.; von Bahr Greenwood, T.; Machowicz, R.; Berliner, N.; Birndt, S.; Gil-Herrera, J.; Girschikofsky, M.; Jordan, M.B.; et al. Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood 2019, 133, 2465–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Samkari, H.; Berliner, N. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2018, 13, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Review of etiologies and management. J. Blood Med. 2014, 5, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, W.; Veer, M.V.; Besser, M. Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: An elusive syndrome. Clin. Med. 2016, 16, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipovich, A.H. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and related disorders. Hematol. ASH Educ. Program 2009, 2009, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani, G.N.; Woda, B.A.; Newburger, P.E. Advances in understanding the pathogenesis of HLH. Br. J. Haematol. 2013, 161, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madkaikar, M.; Shabrish, S.; Desai, M. Current updates on classification, diagnosis and treatment of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). Indian J. Pediatr. 2016, 83, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuriyama, T.; Takenaka, K.; Kohno, K.; Yamauchi, T.; Daitoku, S.; Yoshimoto, G.; Kikushige, Y.; Kishimoto, J.; Abe, Y.; Harada, N.; et al. Engulfment of hematopoietic stem cells caused by down-regulation of CD47 is critical in the pathogenesis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood 2012, 120, 4058–4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, J.M.; Zheleznyak, A.; Chung, J.; Lindberg, F.P.; Sarfati, M.; Frazier, W.A.; Brown, E.J. Role of cholesterol in formation and function of a signaling complex involving αvβ3, integrin-associated protein (CD47), and heterotrimeric G proteins. J. Cell Biol. 1999, 146, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, J.F.; Zheleznyak, A.; Frazier, W.A. Cholesterol-independent interactions with CD47 enhance αvβ3 avidity. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 17301–17311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sick, E.; Jeanne, A.; Schneider, C.; Dedieu, S.; Takeda, K.; Martiny, L. CD47 update: A multifaceted actor in the tumour microenvironment of potential therapeutic interest. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 167, 1415–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Z.; Bian, Z.; Shi, L.; Niu, S.; Ha, B.; Tremblay, A.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Paluszynski, J.; Liu, M.; et al. Loss of cell surface CD47 clustering formation and binding avidity to SIRPα facilitate apoptotic cell clearance by macrophages. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henter, J.I.; Horne, A.; Aricó, M.; Egeler, R.M.; Filipovich, A.H.; Imashuku, S.; Ladisch, S.; McClain, K.; Webb, D.; Winiarski, J.; et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2006, 48, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henter, J.I.; Samuelsson-Horne, A.; Aricò, M.; Egeler, R.M.; Elinder, G.; Filipovich, A.H.; Gadner, H.; Imashuku, S.; Komp, D.; Ladisch, S.; et al. Treatment of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with HLH-94 immunochemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. Blood 2002, 100, 2367–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirillo, A.; Norata, G.D.; Catapano, A.L. LOX-1, OxLDL, and atherosclerosis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 152786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.W.; Yang, E.J.; Yoo, K.H.; Choi, I.H.; Mishra, V.K. Macrophage differentiation from monocytes is influenced by the lipid oxidation degree of low-density lipoprotein. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 235797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soran, H.; Schofield, J.D.; Durrington, P.N. Antioxidant properties of HDL. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brites, F.; Martin, M.; Guillas, I.; Kontush, A. Antioxidative activity of high-density lipoprotein (HDL): Mechanistic insights into potential clinical benefit. BBA Clin. 2017, 8, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahotupa, M. Oxidized lipoprotein lipids and atherosclerosis. Free Radic. Res. 2017, 51, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Leeuwen, H.J.; Heezius, E.C.J.M.; Dallinga, G.M.; van Strijp, J.A.G.; Verhoef, J.; van Kessel, K.P.M. Lipoprotein metabolism in patients with severe sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 31, 1359–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, B.H.; Grossman, J.; Ansell, B.J.; Skaggs, B.J.; McMahon, M. Altered lipoprotein metabolism in chronic inflammatory states: Proinflammatory high-density lipoprotein and accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2008, 10, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, E.J.; Krueger, J.G. Lipoprotein metabolism and inflammation in patients with psoriasis. Am. J. Cardiol. 2016, 118, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, S.; Raman, G.; Vishwanathan, R.; Jacques, P.F.; Johnson, E.J. Dietary cholesterol and cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvente-Poirot, S.; Poirot, M. Cholesterol metabolism and cancer: The good, the bad and the ugly. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2012, 12, 673–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansel, B.; Kontush, A.; Bonnefont-Rousselot, D.; Bruckert, E.; Chapman, M.J. Alterations in lipoprotein defense against oxidative stress in metabolic syndrome. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2006, 8, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balder, J.W.; de Vries, J.K.; Nolte, I.M.; Lansberg, P.J.; Kuivenhoven, J.A.; Kamphuisen, P.W. Lipid and lipoprotein reference values from 133,450 Dutch Lifelines participants: Age- and gender-specific baseline lipid values and percentiles. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2017, 11, 1055–1064.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcinkaya, A.; Unal, S.; Oztas, Y. Altered HDL particle in sickle cell disease: Decreased cholesterol content is associated with hemolysis, whereas decreased apolipoprotein A1 is linked to inflammation. Lipids Health Dis. 2019, 18, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amendola, G.; Danise, P.; Todisco, N.; D’Uurzo, G.; Di Palma, A.; Concilio, R. Lipid profile in β-thalassemia intermedia patients: Correlation with erythroid bone marrow activity. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2007, 29, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allampallam, K.; Dutt, D.; Nair, C.; Shetty, V.; Mundle, S.; Lisak, L.; Andrews, C.; Ahmed, B.; Mazzone, L.; Zorat, F.; et al. The clinical and biologic significance of abnormal lipid profiles in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. J. Hematotherapy Stem Cell Res. 2000, 9, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woollett, L.A.; Shah, A.S. Fetal and neonatal sterol metabolism. In Endotext; Feingold, K.R., Anawalt, B., Boyce, A., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK395580/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Bernecker, C.; Köfeler, H.; Pabst, G.; Trötzmüller, M.; Kolb, D.; Strohmayer, K.; Trajanoski, S.; Holzapfel, G.A.; Schlenke, P.; Dorn, I. Cholesterol deficiency causes impaired osmotic stability of cultured red blood cells. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, C.; Conrard, L.; Guthmann, M.; Pollet, H.; Carquin, M.; Vermylen, C.; Gailly, P.; Van Der Smissen, P.; Mingeot-Leclercq, M.P.; Tyteca, D. Contribution of plasma membrane lipid domains to red blood cell (re)shaping. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraitis, A.G.; Freeman, L.A.; Shamburek, R.D.; Wesley, R.; Wilson, W.; Grant, C.M.; Price, S.; Demosky, S.; Thacker, S.G.; Zarzour, A.; et al. Elevated interleukin-10: A new cause of dyslipidemia leading to severe HDL deficiency. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2015, 9, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, C.; Hu, X.; Li, W.P.; Samuels, S.; Sharif, M.N.; Kotenko, S.; Ivashkiv, L.B. Reprogramming of IL-10 activity and signaling by IFN-γ. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 5034–5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Hu, S.; Xuan, C.; Jin, M.; Ji, Q.; Wang, Y. Interferon gamma and interleukin 10 polymorphisms in Chinese children with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2017, 64, e26465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Farrell, A.M.; Liu, Y.; Moore, K.W.; Mui, A.L. IL-10 inhibits macrophage activation and proliferation by distinct signaling mechanisms: Evidence for Stat3-dependent and -independent pathways. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 1006–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbour, E.; McClain, K.L.; Allen, C.E.; Parikh, S.A.; Otrock, Z.K.; Rojas-Hernandez, C.M.; Blechacz, B.; Wang, S.; Minkov, M.; Jordan, M.B.; et al. A consensus review on malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Cancer 2017, 123, 3229–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, B.; Loike, J.D.; Kako, Y.; Weinstock, P.H.; Breslow, J.L.; Silverstein, S.C.; Goldberg, I.J. Lipoprotein lipase regulates Fc receptor–mediated phagocytosis by macrophages maintained in glucose-deficient medium. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 100, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.L.; Garcia-Arcos, I.; Nyrén, R.; Olivecrona, G.; Kim, J.Y.; Hu, Y.; Agrawal, R.R.; Murphy, A.J.; Goldberg, I.J.; Deckelbaum, R.J. Lipoprotein lipase deficiency impairs bone marrow myelopoiesis and reduces circulating monocyte levels. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henter, J.I.; Carlson, L.A.; Söder, O.; Nilsson-Ehle, P.; Elinder, G. Lipoprotein alterations and plasma lipoprotein lipase reduction in familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Acta Paediatr. 1991, 80, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Wang, L.; Gao, X.; Duan, L.; Shu, Y.; Qiu, H. Prognostic value of lipid profile in adult secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1083088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Dou, Y.; Guan, X.; Guo, Y.; Yu, J. Low total cholesterol level predicts early death in children with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 1006817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yan, H.; Luo, T.; Xiao, Z.; Gong, L.; Huang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, M.; Yao, Z.; Zang, P.; et al. Prognostic value of hypertriglyceridemia and hypofibrinogenemia in pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: A latent class analysis. Orphanet, J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.; Zhang, C.; George, D.; Kotecha, S.; Abdelghaffar, M.; Forster, T.; Santos Rodrigues, P.D.; Reisinger, A.C.; White, D.; Hamilton, F.; et al. Low circulatory levels of total cholesterol, HDL-C and LDL-C are associated with death of patients with sepsis and critical illness: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and perspective of observational studies. EBioMedicine 2024, 100, 104981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ID | Sex | Primary or Secondary HLH | Secondary Cause | LDL (mg/dL) | HDL (mg/dL) | Cholesterol (mg/dL) | TG (mg/dL) | Ferritin (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | Secondary | MDS | 10 | 13 | 56 | 279 | 3106.5 |

| 2 | Male | Secondary | Cisplatin | 110 | 5 | 157 | 208 | 40,163 |

| 3 | Female | Secondary | Still’s disease | 33 | 26 | 78 | 96 | 16,500 |

| 4 | Male | Secondary | EBV | 168 | 5 | 209 | 181 | 16,500 |

| 5 | Male | Secondary | Intravascular DLBCL | 100 | 9 | 162 | 265 | 1356.9 |

| 6 | Male | Secondary | EBV | 35 | 5 | 74 | 168 | 11,873.1 |

| 7 | Female | Secondary | EBV | 64 | 5 | 124 | 275 | 2370.2 |

| 8 | Female | Secondary | CRC | 132 | 5 | 171 | 172 | 16,500 |

| 9 | Male | Secondary | Idiopathic | 134 | 5 | 206 | 334 | 33,000 |

| 10 | Male | Secondary | Idiopathic | 54 | 8 | 157 | 747 | 16,500 |

| 11 | Female | Secondary | CMV | 1 | 10 | 57 | 363 | 3977.9 |

| 12 | Female | Secondary | SLE, autoimmune hepatitis | 1 | 5 | 82 | 381 | 1814.2 |

| 13 | Male | Primary | N/A | 58 | 24 | 106 | 120 | 5868.4 |

| 14 | Male | Secondary | Viral | 35 | 20 | 137 | 1013 | 14,800 |

| 15 * | Male | Secondary | T-cell lymphoma | 10 | 7 | 85 | 342 | 8330 |

| 16 * | Female | Secondary | Idiopathic | 10 | 7 | 162 | 1658 | 1332 |

| 17 * | Female | Secondary | Idiopathic | 10 | 7 | 90 | 390 | 20,294 |

| 18 | Male | Secondary | Idiopathic | 658 | 6 | 727 | 440 | 16,500 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reap, L.; Mynam, R.S.; Takiar, R.; Ma, V.T. Acquired Hypolipoproteinemia and Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis: A Case Series and Review. Hematol. Rep. 2025, 17, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep17050050

Reap L, Mynam RS, Takiar R, Ma VT. Acquired Hypolipoproteinemia and Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis: A Case Series and Review. Hematology Reports. 2025; 17(5):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep17050050

Chicago/Turabian StyleReap, Leo, Ritwick S. Mynam, Radhika Takiar, and Vincent T. Ma. 2025. "Acquired Hypolipoproteinemia and Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis: A Case Series and Review" Hematology Reports 17, no. 5: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep17050050

APA StyleReap, L., Mynam, R. S., Takiar, R., & Ma, V. T. (2025). Acquired Hypolipoproteinemia and Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis: A Case Series and Review. Hematology Reports, 17(5), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep17050050