Adaptability, Yield Stability, and Agronomic Performance of Improved Purple Corn (Zea mays L.) Hybrids Across Diverse Agro-Ecological Zones in Peru

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Plant Material and Treatments

2.3. Experimental Design and Agronomic Management

2.4. Agronomic Traits Measured

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Plant Height (cm)

3.2. Anthesis–Silking Interval (ASI)

3.3. Cob Rot (%)

3.4. Field Weight (kg)

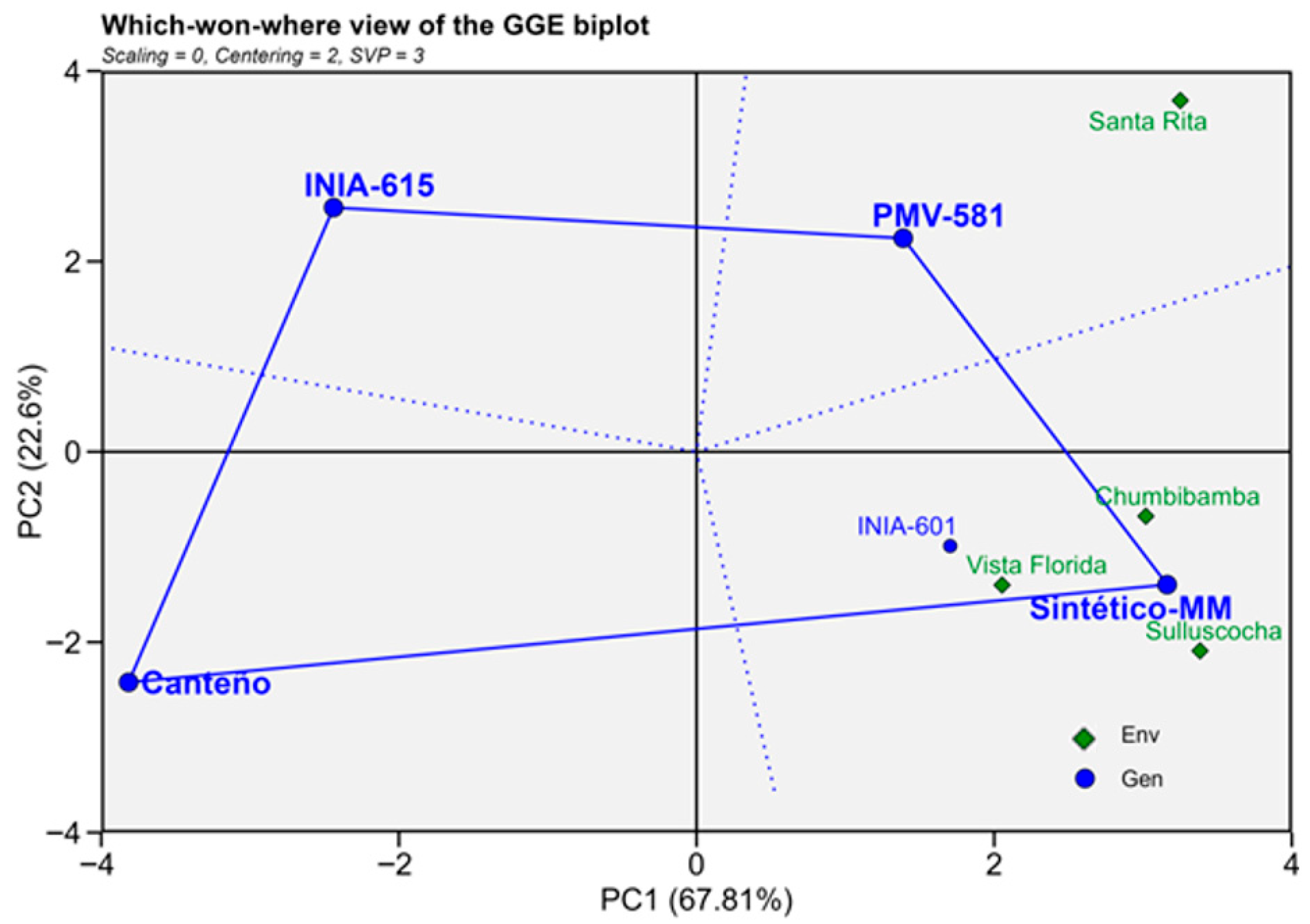

3.5. Grain Yield (t/ha)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministerio del Ambiente (MINAM). Línea de Base de la Diversidad Genética del Maíz Peruano con Fines de Bioseguridad; Grupo Raso: Lima, Perú, 2018; 144p. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, A.; Narro, L.; Chávez, A. Cultivo de maíz morado (Zea mays L.) en zona altoandina de Perú: Adaptación e identificación de cultivares de alto rendimiento y contenido de antocianina. Sci. Agropecu. 2020, 11, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedreschi, R.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L. Antioxidant phytochemicals and oxidative stress: A review. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2007, 13, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Hu, M.J.; Wang, Y.Q.; Cui, Y.L. Antioxidant activities of quercetin and its complexes for medicinal application. Molecules 2019, 24, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coșarcă, S.; Tanase, C.; Muntean, D.L. Therapeutic aspects of catechin and its derivatives—An update. Acta Biol. Marisiensis 2019, 2, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felter, S.P.; Zhang, X.; Thompson, C. Butylated hydroxyanisole: Carcinogenic food additive to be avoided or harmless antioxidant important to protect food supply? Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 121, 104887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.; Chen, X.; Chen, T. Anthocyanins in colorectal cancer prevention review. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wu, X.; Han, L.; Bian, J.; He, C.; El-Omar, E.; Wang, M. The potential roles of dietary anthocyanins in inhibiting vascular endothelial cell senescence and preventing cardiovascular diseases. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIDAGRI. Análisis de Mercado: 2015–2021. Maíz Morado; MIDAGRI: Lima, Perú, 2022; Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/agromercado/informes-publicaciones/2624383-analisis-de-mercado-maiz-morado-2015-2021 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Yue, H.; Olivoto, T.; Bu, J.; Wei, J.; Liu, P.; Wu, W.; Nardino, M.; Jiang, X. Assessing the role of genotype by environment interaction as determinants of maize grain yield and lodging resistance. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bänziger, M.; Cooper, M. Breeding for low-input conditions and consequences for participatory plant breeding: Examples from tropical maize and wheat. Euphytica 2001, 122, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Holland, J.B. A heritability-adjusted GGE biplot for test environment evaluation. Euphytica 2010, 171, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.; Messina, C.D.; Podlich, D.; Totir, L.R.; Baumgarten, A.; Hausmann, N.J.; Graham, G. Predicting the future of plant breeding: Complementing empirical evaluation with genetic prediction. Crop Pasture Sci. 2014, 65, 311–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.B.; Cheng, B.; Peterson, G.W. Genetic diversity analysis of yellow mustard (Sinapis alba L.) germplasm based on genotyping by sequencing. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2014, 61, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadesa, L. Review on genetic-environmental interaction (GxE) and its application in crop breeding. Int. J. Res. Agron. 2022, 5, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye, M.; Adam, M.; Ganyo, K.K.; Guissé, A.; Cissé, N.; Muller, B. Genotype–Environment Interaction: Trade-Offs between the Agronomic Performance and Stability of Dual-Purpose Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) Genotypes in Senegal. Agronomy 2019, 9, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Lee, H.-S.; Lee, C.-M.; Ha, S.-K.; Park, H.-M.; Lee, S.-M.; Kwon, Y.; Jeung, J.-U.; Mo, Y. Multi-Environment Trials and Stability Analysis for Yield-Related Traits of Commercial Rice Cultivars. Agriculture 2023, 13, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvick, D.N. The Contribution of Breeding to Yield Advances in maize (Zea mays L.). Adv. Agron. 2005, 86, 83–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epinat-Le Signor, C.; Dousse, S.; Lorgeou, J.; Denis, J.; Bonhomme, R.; Carolo, P.; Charcosset, A. Interpretation of genotype x environment interactions for early maize hybrids over 12 years. Crop Sci. 2001, 41, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu’quez, J.E.; Aguirrezábal, L.A.N.; Agüero, M.E.; Pereyra, V.R. Stability and adaptability of cultivars in non-balanced yield trials: Comparison of methods for selecting ‘high oleic’ sunflower hybrids for grain yield and quality. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2002, 188, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Kang, M.S.; Ma, B.; Woods, S.; Cornelius, P.L. GGE Biplot vs. AMMI Analysis of Genotype-by-Environment Data. Crop Sci. 2007, 47, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauch, H.G. A simple protocol for AMMI analysis of yield trials. Crop Sci. 2013, 53, 1860–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohane, E.N.; Shimelis, H.; Laing, M.; Mathew, I.; Shayanowako, A. Genotype-by-environment interaction and stability analyses of grain yield in pigeonpea [Cajanus cajan (L.) Millspaugh]. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B Soil Plant Sci. 2021, 71, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singamsetti, A.; Shahi, J.P.; Zaidi, P.H.; Seetharam, K.; Vinayan, M.T.; Kumar, M.; Madankar, K. Genotype × environment interaction and selection of maize (Zea mays L.) hybrids across moisture regimes. Field Crops Res. 2021, 270, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsenios, N.; Sparangis, P.; Leonidakis, D.; Katsaros, G.; Kakabouki, I.; Vlachakis, D.; Efthimiadou, A. Effect of Genotype × Environment Interaction on Yield of Maize Hybrids in Greece Using AMMI Analysis. Agronomy 2021, 11, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaei, S.H.; Mostafavi, K.; Omrani, A.; Omrani, S.; Nasir Mousavi, S.M.; Illés, Á.; Nagy, J. Yield stability analysis of maize (Zea mays L.) hybrids using parametric and AMMI methods. Scientifica 2021, 2021, 5576691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocianowski, J.; Nowosad, K.; Rejek, D. Genotype–environment interaction for grain yield in maize (Zea mays L.) using the additive main effects and multiplicative interaction (AMMI) model. J. Appl. Genet. 2024, 65, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, G.; García-Ramírez, A.; Reynaga-Franco, F.J.; Mendívil-Mendoza, J.E.; Ochoa Meza, A.R.; Cervantes-Ortiz, F.; Andrio Enriquez, E. Rendimiento y componentes agronómicos en híbridos de maíz morado (Zea mays L.) usando el modelo AMMI. An. Cienc. 2023, 84, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobel, R.W.; Wright, M.J.; Gauch, H.G. Statistical analysis of a yield trial. Agron. J. 1988, 80, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivoto, T.; Lúcio, A.D.C.; Da Silva, J.A.G.; Sari, B.G.S.; Diel, M.I. Mean performance and stability in multi-environment trials II: Selection based on multiple traits. Agron. J. 2019, 111, 2961–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Tinker, N.A. Biplot analysis of multi-environment trial data: Principles and applications. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2006, 86, 623–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivoto, T.; Lúcio, A.D. metan: An R package for multi-environment trial analysis. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2020, 11, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, M. Genotype by environment interaction and yield stability analysis of open pollinated maize varieties using AMMI model in Afar Regional State, Ethiopia. J. Plant Breed. Crop Sci. 2020, 12, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abanto, W.; Medina, A.; Injante, P. Maíz Morado INIA 601: Variedad de Maíz Morado para la Sierra Norte del Perú; Plegable No. 3-2014; Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria (INIA): Cajamarca, Perú, 2014; Available online: https://repositorio.inia.gob.pe/handle/20.500.12955/65 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Estación Experimental Agraria Cañaán–Ayacucho. Maíz INIA 615—Negro Cañaán: Nueva Variedad de Maíz Morado para la Sierra Peruana; Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria (INIA): Lima, Perú, 2007; Available online: https://repositorio.inia.gob.pe/handle/20.500.12955/648 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Atalaya, M.R.; Hoyos, A.M. Estudio comparativo de las características agronómicas y químicas de tres cultivares de maíz morado en Perú. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agric. 2022, 13, 953–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo, W.S. Maíz Blanco Urubamba (Blanco Gigante Cuzco); Manual Técnico No. 13; Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria (INIA): Cusco, Perú, 2013; Available online: https://repositorio.inia.gob.pe/handle/20.500.12955/87 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Manrique, A. El Maíz Morado Peruano; Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria (INIA): Lima, Perú, 2000; Available online: https://repositorio.inia.gob.pe/items/d5d896b6-4487-4f07-99fa-29cf2b02fcad (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Mafouasson, H.N.A.; Gracen, V.; Yeboah, M.A.; Ntsomboh-Ntsefong, G.; Tandzi, L.N.; Mutengwa, C.S. Genotype-by-Environment Interaction and Yield Stability of Maize Single Cross Hybrids Developed from Tropical Inbred Lines. Agronomy 2018, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Liu, C.; Ye, Z. Influence of genotype × environment interaction on yield stability of maize hybrids with AMMI model and GGE biplot. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, R.; Amri, A.; Haghparast, R.; Sadeghzadeh, D.; Armion, M.; Ahmadi, M.M. Pattern analysis of genotype-by-environment interaction for grain yield in durum wheat. J. Agric. Sci. 2009, 147, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.A.; Wang, X.; Zafar, S.A.; Noor, M.A.; Hussain, H.A.; Nawaz, M.A.; Farooq, M. Thermal stresses in maize: Effects and management strategies. Plants 2021, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitah, M.; Malec, K.; Maitah, K. Influence of precipitation and temperature on maize production in the Czech Republic from 2002 to 2019. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Hernández, N.A.; Martínez Sifuentes, A.R.; Halecki, W.; Trucíos Caciano, R.; Rodríguez Moreno, V.M. An assessment of the impact of climate change on maize production in northern Mexico. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Aquino, V.; Ignacio-Cárdenas, S.; Japa-Espinoza, A.J.; Campos-Félix, U.; Ciriaco-Poma, J.; Campos-Félix, A.; Pantoja-Medina, B.; Dávalos-Prado, J.Z. Influence of climatic parameters and plant morphological characters on the total anthocyanin content of purple maize (Zea mays L., PMV-581) cob core. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakabayashi, R.; Saito, K. Integrated metabolomics for abiotic stress responses in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015, 24, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naing, A.H.; Kim, C.K. Abiotic stress-induced anthocyanins in plants: Their role in tolerance to abiotic stresses. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 1711–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovinich, N.; Kayanja, G.; Chanoca, A.; Otegui, M.S.; Grotewold, E. Abiotic stresses induce different localizations of anthocyanins in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal. Behav. 2015, 10, e1027850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Li, J.; Lin, X.; Wang, L.; Yang, X.; Xia, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Li, H.; Deng, X.; et al. Changes in plant anthocyanin levels in response to abiotic stresses: A meta-analysis. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2022, 16, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrović, B.; Stanisavljević, D.; Treski, S.; Stojaković, M.; Ivanović, M.; Bekavac, G.; Rajković, M. Evaluation of experimental maize hybrids tested in multi-location trials using AMMI and GGE biplot analyses. Turk. J. Field Crop 2012, 17, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hongyu, K.; García-Peña, M.; Araújo, L.; Santos Dias, C. Statistical analysis of yield trials by AMMI analysis of genotype–environment interaction. Biom. Lett. 2014, 51, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo Júnior, L.A.Y.; de Silva, C.P.; de Oliveira, L.A.; Nuvunga, J.J.; Pires, L.P.M.; Von Pinho, R.G.; Balestre, M. AMMI Bayesian Models to Study Stability and Adaptability in Maize. Agron. J. 2018, 110, 1765–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, H.J.; Atlin, G.; Payne, T. Multi-location testing as a tool to identify plant response to global climate change. In Climate Change and Crop Production; Reynolds, M., Ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2010; pp. 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Kang, M.S.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, J.; Xu, C. Yield Stability of Maize Hybrids Evaluated in Multi-Environment Trials in Yunnan, China. Agron. J. 2007, 99, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.C.D.; Pereira, C.H.; Nunes, J.A.R.; Lepre, A.L. Adaptability and stability of maize hybrids in unreplicated multienvironment trials. Rev. Ciênc. Agron. 2019, 50, e20190010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uberti, A.; Rezende, W.M.; Caixeta, D.G.; Reis, H.M.; Resende, N.C.V.; Destro, V.; DeLima, R.O. Assessment of yield performance and stability of hybrids and populations of tropical maize across multiple environments in Southeastern Brazil. Crop Sci. 2023, 63, 2012–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.L.; Ceccarelli, S.; Blair, M.W.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Are, A.K.; Ortiz, R. Landrace Germplasm for Improving Yield and Abiotic Stress Adaptation. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvick, D.N. What is yield? In Developing Drought and Low N-Tolerant Maize, Proceedings of a Symposium, CIMMYT, El Batán, Mexico, 25–29 March 1996; Edmeades, G.O., Bänziger, B., Mickelson, H.R., Peña-Valdivia, C., Eds.; CIMMYT: Mexico City, Mexico, 1997; pp. 332–335. [Google Scholar]

- Araus, J.L.; Serret, M.D.; Edmeades, G.O. Phenotyping maize for adaptation to drought. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollenaar, M.; Lee, E.A. Dissection of physiological processes underlying grain yield in maize by examining genetic improvement and heterosis. Maydica 2006, 51, 399. [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna, B.M.; Cairns, J.E.; Zaidi, P.H.; Beyene, Y.; Makumbi, D.; Gowda, M.; Magorokosho, C.; Zaman-Allah, M.; Olsen, M.; Das, A.; et al. Beat the stress: Breeding for climate resilience in maize for the tropical rainfed environments. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 1729–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.S. A Rank-Sum Method for Selecting High-Yielding, Stable Corn Genotypes. Cereal Res. Commun. 1988, 16, 113–115. [Google Scholar]

- Nyombayire, A.; Derera, J.; Sibiya, J.; Ngaboyisonga, C. Genotype × Environment Interaction and Stability Analysis for Grain Yield of Diallel Cross Maize Hybrids Across Tropical Medium and Highland Ecologies. J. Plant Sci. 2018, 6, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Crossa, J.; Gauch, H.G., Jr.; Zobel, R.W. Additive Main Effects and Multiplicative Interaction Analysis of Two International Maize Cultivar Trials. Crop Sci. 1990, 30, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubičić, N.; Popović, V.; Kostić, M.; Pajić, M.; Buđen, M.; Gligorević, K.; Dražić, M.; Bižić, M.; Crnojević, V. Multivariate Interaction Analysis of Zea mays L. Genotypes Growth Productivity in Different Environmental Conditions. Plants 2023, 12, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour-Aboughadareh, A.; Khalili, M.; Poczai, P.; Olivoto, T. Stability indices to deciphering the genotype-by-environment interaction (GEI) effect: An applicable review for use in plant breeding programs. Plants 2022, 11, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, D.C.; de Leon, N.; Kaeppler, S.M. Utility of anthesis–silking interval information to predict grain yield under water and nitrogen limited conditions. Crop Sci. 2022, 63, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Hao, Z.; Pang, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, N.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Wang, L.; Xu, M. Effect of water-deficit on tassel development in maize. Gene 2019, 681, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolaños, J.; Edmeades, G.O. The Importance of the Anthesis-Silking Interval in Breeding for Drought Tolerance in Tropical Maize. Field Crops Res. 1996, 48, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrás, L.; Vitantonio-Mazzini, L.N. Maize reproductive development and kernel set under limited plant growth environments. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 3235–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.C.; Moon, J.-C.; Kim, J.Y.; Song, K.; Kim, K.-H.; Lee, B.-M. Evaluation of Drought Tolerance using Anthesis-silking Interval in Maize. Korean J. Crop Sci. 2017, 62, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, P.F.; Bolaños, J.; Edmeades, G.O.; Eaton, D.L. Gains from Selection under Drought versus Multilocation Testing in Related Tropical Maize Populations. Crop Sci. 1995, 35, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmeades, G.O.; Bolanos, J.; Elings, A.; Ribaut, J.M.; Bänziger, M.; Westgate, M.E. The role and regulation of the anthesis-silking interval in maize. In Physiology and Modeling Kernel Set in Maize; CSSA Special Publications; Crop Science Society of America (CSSA): Madison, WI, USA, 2000; Volume 29, pp. 43–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monneveux, P.; Sanchez, C.; Tiessen, A. Future progress in drought tolerance in maize needs new secondary traits and cross combinations. J. Agric. Sci. 2008, 146, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmeades, G.O. Progress in achieving and delivering drought tolerance in maize–An update. In Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops; The International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications (ISAAA): Ithaca, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Deressa, T.; Adugna, G.; Suresh, L.M.; Bekeko, Z.; Opoku, J.; Vaughan, M.; Prasanna, B.M. Biophysical factors and agronomic practices associated with Fusarium ear rot and fumonisin contamination of maize in multiple agroecosystems in Ethiopia. Crop Sci. 2024, 64, 827–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesterhazy, A.; Szabo, B.; Szieberth, D.; Tóth, S.; Nagy, Z.; Meszlenyi, T.; Herczig, B.; Berenyi, A.; Tóth, B. Stability of Resistance of Maize to Ear Rots (Fusarium graminearum, F. verticillioides and Aspergillus flavus) and Their Resistance to Toxin Contamination and Conclusions for Variety Registración. Toxins 2024, 16, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lana, F.D.; Paul, P.A.; Minyo, R.; Thomison, P.; Madden, L.V. Stability of Hybrid Maize Reaction to Gibberella Ear Rot and Deoxynivalenol Contamination of Grain. Phytopathology 2020, 110, 1908–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Physicochemical Properties | Units | Environment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vista Florida | Santa Rita | Chumbibamba | Sulluscocha | ||

| pH | unid. pH | 7.7 | 7.7 | 6.5 | 8.1 |

| Electrical conductivity | mS/m | 3.1 | 117.4 | 3.6 | 11.5 |

| Organic matter | % | 1.25 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 4.0 |

| Nitrogen | % | - | - | 0.13 | - |

| Available phosphorus | mg/kg | 6.6 | 69.5 | 57.8 | 13.9 |

| Available potassium | mg/kg | 128 | 813.38 | 146.38 | 277.1 |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent | % | 3.06 | 2.1 | - | 12.69 |

| SoilTexture | |||||

| Sand | % | 60 | 78.6 | 48 | - |

| Silt | % | 17 | 10.2 | 22 | - |

| Clay | % | 23 | 11.2 | 30 | - |

| Textural Class | Sandy clay loam | Loam | Clay loam | Clay loam | |

| Genotype | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| INIA 601 | This variety was developed in 1990 at the Cajabamba Experimental Station. It originated from a population of 256 progenies, comprising 108 derived from the purple corn variety Caraz and 148 from the local variety Negro Bañosbamba. INIA-601 is characterized by a plant height of 2.16 m, female flowering at 98 days, a thousand-seed weight of 456.2 g, and an average grain yield of 3.0 t ha−1. | [34] |

| INIA 615 | Developed from 36 collections of Kully-race local cultivars gathered in 1990 from the provinces of Huanta, Huamanga, and San Miguel, this variety was refined through nine consecutive cycles of half-sib recurrent selection. It was improved through nine cycles of half-sib recurrent selection. INIA-615 exhibits the following characteristics: plant height of 2.28 m, female flowering between 84 and 92 days, and an average commercial yield of 7.8 t ha−1. | [35] |

| Canteño | Derived from the Cuzco race, this variety represents the predominant purple corn consumed in Lima. It is characterized by large kernels arranged in well-defined rows on the cob. The Canteño variety shows an average grain yield ranging from 1.50 to 1.90 t ha−1. | [2,36,37] |

| PMV 581 | PMV-581 is an improved purple corn genotype developed at the Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina using germplasm derived from Morado de Caraz. It has an intermediate growth cycle and produces elongated, medium-sized ears (15–20 cm) with high anthocyanin content. Under well-managed production conditions, PMV-581 can reach grain yields of up to 6 t ha−1. | [38] |

| Sintético-MM | Morado Mejorado (MM) is a synthetic purple corn variety derived from INIA 601 and developed through recurrent selection of S1 progenies at the Baños del Inca Experimental Station (INIA–Peru). | [2] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Garcia, G.; Montero, F.; Torres, M.E.; Alvarez, S.; Vasquez, W.; Villantoy, A.; Ruiz, Y.; Escobal, F.; Cántaro-Segura, H.; Paitamala, O.; et al. Adaptability, Yield Stability, and Agronomic Performance of Improved Purple Corn (Zea mays L.) Hybrids Across Diverse Agro-Ecological Zones in Peru. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2026, 17, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb17010003

Garcia G, Montero F, Torres ME, Alvarez S, Vasquez W, Villantoy A, Ruiz Y, Escobal F, Cántaro-Segura H, Paitamala O, et al. Adaptability, Yield Stability, and Agronomic Performance of Improved Purple Corn (Zea mays L.) Hybrids Across Diverse Agro-Ecological Zones in Peru. International Journal of Plant Biology. 2026; 17(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb17010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcia, Gilberto, Fernando Montero, Maria Elena Torres, Selwyn Alvarez, Wildo Vasquez, Abraham Villantoy, Yoel Ruiz, Fernando Escobal, Hector Cántaro-Segura, Omar Paitamala, and et al. 2026. "Adaptability, Yield Stability, and Agronomic Performance of Improved Purple Corn (Zea mays L.) Hybrids Across Diverse Agro-Ecological Zones in Peru" International Journal of Plant Biology 17, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb17010003

APA StyleGarcia, G., Montero, F., Torres, M. E., Alvarez, S., Vasquez, W., Villantoy, A., Ruiz, Y., Escobal, F., Cántaro-Segura, H., Paitamala, O., & Matsusaka, D. (2026). Adaptability, Yield Stability, and Agronomic Performance of Improved Purple Corn (Zea mays L.) Hybrids Across Diverse Agro-Ecological Zones in Peru. International Journal of Plant Biology, 17(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb17010003