Integrating the Genomic Revolution into Newborn Screening: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Metabolomic-Based Newborn Screening: The Current Worldwide Situation

3. Genome-Based Newborn Screening

| Continent/Country | Newborn Screening | Key Characteristics | Genomic Screening | Specific Geographical Area | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | Traditional NBS (RUSP) | Mandatory, state-funded screening for a Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP), currently covering over 35 core disorders. | BabySeq [16,17,18], BeginNGS [121], GUARDIAN [112,113] | Boston, San Diego, New York | Studies exploring the clinical utility and ethical implications of whole-genome/exome sequencing (WGS/WES) in newborns |

| Australia | Expanded NBS | Metabolic (biochemical) and DNA. | BabyScreen+ [117] | Victoria State | Large research study assessing the feasibility of adding genomic sequencing (500+ conditions) to the heel-prick test. |

| Western Europe | National/regional programs | Comprehensive programs covering 30–50+ disorders using MS/MS and targeted DNA as second-tier test. | Screen4Care [115,116,122,123] | Italy, France, Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, etc. | Major European initiative aiming to integrate genomic data into NBS for early diagnosis of rare diseases (RDs). |

| The Generation Study [114] | UK | Large-scale, genomic research project integrating WGS into the NHS structure (700+ conditions). | |||

| BabyDetect [118] | Belgium | A complementary program using targeted NGS to screen for 100+ conditions, exceeding the standard national panel. | |||

| Italian Regional Projects: RING-Lombardia [124] | Lombardia Region | Explores clinical and organizational aspects of genomic NBS, focusing on three WGS scenarios. | |||

| Genoma Puglia Program [125] | Puglia Region | First publicly funded, structural regional program offering WES/targeted sequencing for ~400 rare diseases. | |||

| ASIA | Varies widely | Some nations have established programs; others are gradually expanding but often lack uniformity. | China Neonatal Genomes Project (CNGP) [119] | China | Aims to sequence 100,000 newborns over 5 years to create a Chinese reference genetic database. |

| Taiwan BabySeq Initiative (TBSI) [120] | Taiwan | Collaboration (started in 2024) to launch a pilot program similar to the American BabySeq. |

4. Neonatal Genomic Screening: Active Projects in Italy

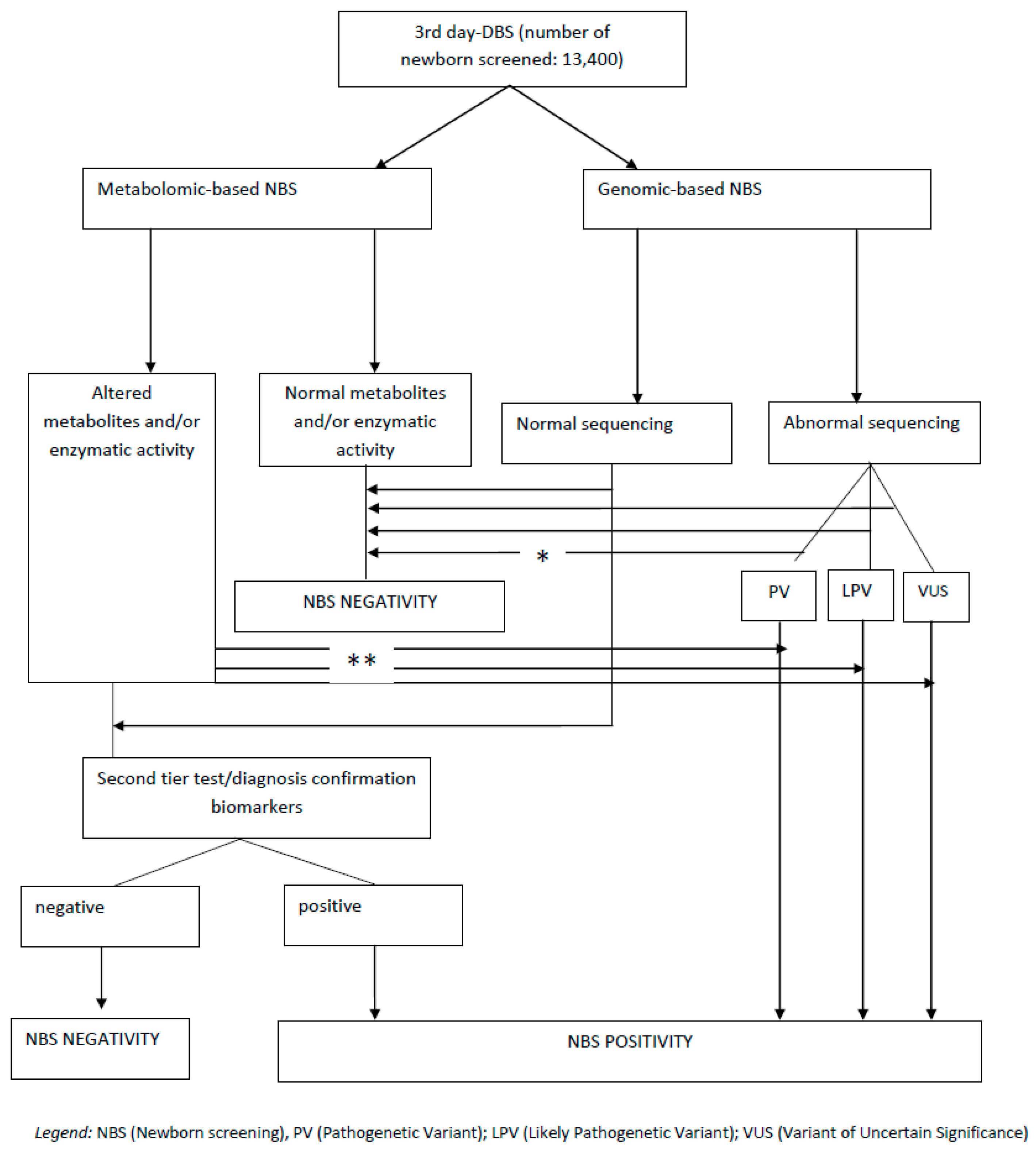

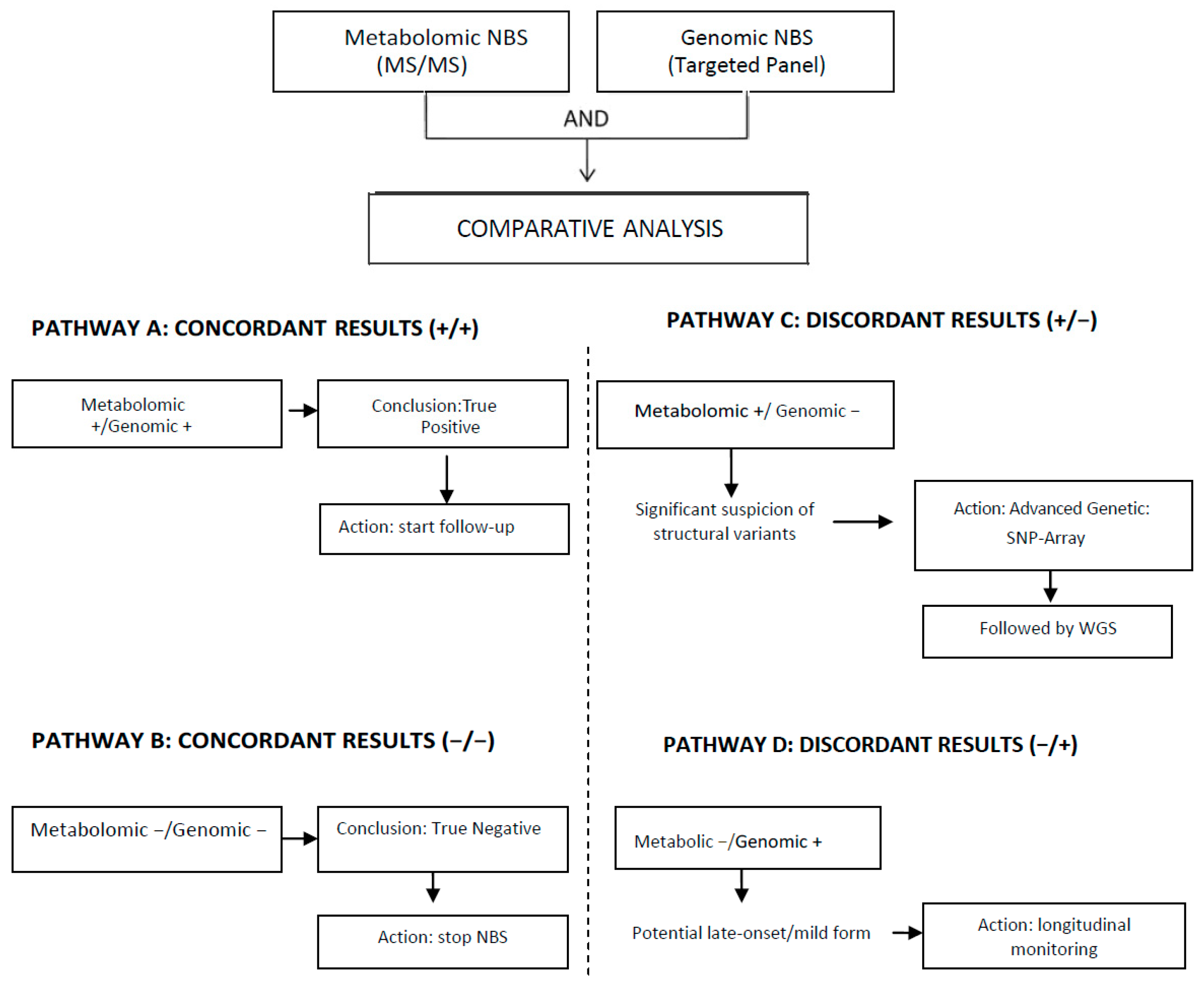

5. Existing Models of Multi-Omics Integration in Newborn Screening

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Screening for inborn errors of metabolism. Report of a WHO Scientific Group. In World Health Organization Technical Report Series; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1968; Volume 401, pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klein, A.H.; Agustin, A.V.; Foley, T.P. Successful laboratory screening for congenital hypothyroidism. Lancet 1974, 2, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthrie, R.; Susi, A. A simple phenylalanine method for detecting phenylketonuria in large populations of newborn infants. Pediatrics 1963, 32, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, H.L. Robert Guthrie and the trials and tribulations of newborn screening. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2021, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Spronsen, F.J.; Blau, N.; Harding, C.; Burlina, A.; Longo, N.; Bosch, A.M. Phenylketonuria. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, O.; Cochrane, B.; Wildgoose, J.; Pinto, A.; Evans, S.; Daly, A.; Ashmore, C.; MacDonald, A. Phenylalanine free infant formula in the dietary management of phenylketonuria. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2023, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichter-Konecki, U.; Vockley, J. Phenylketonuria: Current Treatments and Future Developments. Drugs 2019, 79, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlina, A.; Biasucci, G.; Carbone, M.T.; Cazzorla, C.; Paci, S.; Pochiero, F.; Spada, M.; Tummolo, A.; Zuvadelli, J.; Leuzzi, V. Italian national consensus statement on management and pharmacological treatment of phenylketonuria. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, M.S.; Ozand, P.T.; Bucknall, M.P.; Little, D. Diagnosis of inborn errors of metabolism from blood spots by acylcarnitines and amino acids profiling using automated electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Pediatr. Res. 1995, 38, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hove, J.L.; Chace, D.H.; Kahler, S.G.; Millington, D.S. Acylcarnitines in amniotic fluid: Application to the prenatal diagnosis of propionic acidaemia. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1993, 16, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zytkovicz, T.H.; Fitzgerald, E.F.; Marsden, D.; Larson, C.A.; Shih, V.E.; Johnson, D.M.; Strauss, A.W.; Comeau, A.M.; Eaton, R.B.; Grady, G.F. Tandem Mass Spectrometric Analysis for Amino, Organic, and Fatty Acid Disorders in Newborn Dried Blood Spots: A Two-Year Summary from the New England Newborn Screening Program. Clin. Chem. 2001, 47, 1945–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwu, W.L.; Huang, A.C.; Chen, J.S.; Hsiao, K.J.; Tsai, W.Y. Neonatal screening and monitoring system in Taiwan. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2003, 34, 91–93. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, M.S.; Mann, M.Y.; Lloyd-Puryear, M.A.; Rinaldo, P.; Howell, R.R. Newborn screening: Toward a uniform screening panel and system—Executive summary. Pediatrics 2006, 117, S296–S307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruoppolo, M.; Malvagia, S.; Boenzi, S.; Carducci, C.; Dionisi-Vici, C.; Teofoli, F.; Burlina, A.; Angeloni, A.; Aronica, T.; Bordugo, A.; et al. Expanded Newborn Screening in Italy Using Tandem Mass Spectrometry: Two Years of National Experience. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2022, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, L.; Sohn, H.; Brower, A. Newborn sequencing is only part of the solution for better child health. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2023, 25, 100581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wojcik, M.H.; Gold, N.B. Implications of genomic newborn screening for infant mortality. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2023, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, A.; Ponsaran, R.; Gaviglio, A.; Simancek, D.; Tarini, B.A. Genomics and newborn screening: Perspectives of public health programs. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2022, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woerner, A.C.; Gallagher, R.C.; Vockley, J.; Adhikari, A.N. The use of whole genome and exome sequencing for newborn screening: Challenges and opportunities for population health. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 663752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackley, M.P.; Agrawal, P.B.; Ali, S.S.; Archibald, A.D.; Dawson-McClaren, B.; Ellard, H.; Freeman, L.; Gu, Y.; Jayasinghe, K.; Jiang, S.; et al. Genomic sequencing technologies for rare disease in mainstream healthcare: The current state of implementation. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2025, 33, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wu, D.; Zhu, L.; Wang, W.; Yang, R.; Yang, J.; He, Q.; Zhu, B.; You, Y.; Xiao, R.; et al. Application of a next-generation sequencing (NGS) panel in newborn screening efficiently identifies inborn disorders of neonates. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.L.; Qian, G.L.; Wu, D.W.; Miao, J.K.; Yang, X.; Wu, B.Q.; Yan, Y.Q.; Li, H.B.; Mao, X.M.; He, J.; et al. A multicenter prospective study of next-generation sequencing-based newborn screening for monogenic genetic diseases in China. World J. Pediatr. 2023, 19, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, M.; Bonham, J.R.; Dionisi-Vici, C.; Prevot, J.; Pergent, M.; Meyts, I.; Mahlaoui, N.; Schielen, P.C. Newborn screening as a fully integrated system to stimulate equity in neonatal screening in Europe. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2022, 13, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strand, J.; Gul, K.A.; Erichsen, H.C.; Lundman, E.; Berge, M.C.; Trømborg, A.K.; Sørgjerd, L.K.; Ytre-Arne, M.; Hogner, S.; Halsne, R.; et al. Second-tier next generation sequencing integrated in nationwide newborn screening provides rapid molecular diagnostics of severe combined immunodeficiency. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.M.; Jungner, Y.G. Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease; Public Health Papers, No. 34; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1968.

- Thompson, K.; Atkinson, S.; Kleyn, M. Use of online newborn screening educational resources for the education of expectant parents: An improvement in equity. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2022, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikonja, J.; Groselj, U.; Scarpa, M.; la Marca, G.; Cheillan, D.; Kölker, S.; Zetterström, R.H.; Kožich, V.; Le Cam, Y.; Gumus, G.; et al. Towards achieving equity and innovation in newborn screening across Europe. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2022, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeber, J.G.; Platis, D.; Zetterström, R.H.; Almashanu, S.; Boemer, F.; Bonham, J.R.; Borde, P.; Brincat, I.; Cheillan, D.; Dekkers, E.; et al. Neonatal screening in Europe revisited: An ISNS perspective on the current state and developments since 2010. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2021, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koracin, V.; Mlinaric, M.; Baric, I.; Brincat, I.; Djordjevic, M.; Drole Torkar, A.; Fumic, K.; Kocova, M.; Milenkovic, T.; Moldovanu, F.; et al. Current status of newborn screening in Southeastern Europe. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 648939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- la Marca, G. La organización del cribado neonatal en Italia: Comparación con Europa y el resto del mundo. Rev. Española Salud Pública 2021, 95, e202101007. [Google Scholar]

- Decreto del Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri (DPCM). Aggiornamento dei Livelli Essenziali di Assistenza (LEA), con Estensione dello Screening Neonatale a 8 Nuove Malattie Genetiche Rare (Incluse SMA e SCID) e Revisione di Altre Prestazioni. Available online: https://www.statoregioni.it/it/conferenza-stato-regioni/sedute-2025/seduta-del-23-ottobre-2025/convocazione-e-odg-del-23-ottobre-2025/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Burlina, A.B.; Polo, G.; Rubert, L.; Gueraldi, D.; Cazzorla, C.; Duro, G.; Salviati, L.; Burlina, A.P. Implementation of Second-Tier Tests in Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Disorders in North Eastern Italy. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2019, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munck, A.; Gauthereau, V.; Czernichow, P. Organisation du dépistage néonatal en France. Med. Sci. 2021, 37, 457–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutant, R.; Feillet, F. Présentation de l’état des lieux du dépistage néonatal en France. Med. Sci. 2018, 34, 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haute Autorité de Santé. Évaluation a Priori de L’extension du Dépistage Néonatal à une ou Plusieurs Erreurs Innées du Métabolisme par Spectrométrie de Masse en Tandem. Volet 2. 2020. Available online: https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/c_2866458/fr/evaluation-a-priori-de-l-extension-du-depistage-neonatal-a-une-ou-plusieurs-erreurs-innees-dumetabolisme-par-spectrometrie-de-masse-en-tandem-volet-2 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Dikow, N.; Ditzen, B.; Kölker, S.; Hoffmann, G.F.; Schaaf, C.P. From newborn screening to genomic medicine: Challenges and suggestions on how to incorporate genomic newborn screening in public health programs. Med. Genet. 2022, 34, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tönnies, H.; Nennstiel, U. Newborn screening in Germany. Med. Genet. 2022, 34, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, S.; Dubois, M.; Van Coster, R.; Godefridis, G. Neonatal screening in Belgium: A comprehensive overview of current practices and challenges. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 182, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Belgian Federal Public Service Health, Food Chain Safety and Environment. Official National Newborn Screening Program; Belgian FPS Health: Brussels, Belgium.

- UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC). Newborn and Infant Physical Examination (NIPE) and Newborn Screening for Inherited Metabolic Diseases; UK NSC: London, UK, 2025.

- Public Health England. NHS Screening Programmes. In NHS Newborn Blood Spot Screening Programme Handbook; PHE: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM). RIVM National Neonatal Screening Programme; RIVM: Bilthoven, The Netherlands.

- Jansen, M.E.; Klein, A.W.; Buitenhuis, E.C.; Rodenburg, W.; Cornel, M.C. Expanded Neonatal Bloodspot Screening Programmes: An Evaluation Framework to Discuss New Conditions with Stakeholders. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 635353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rosenau, H.; Steffen, F. Legal aspects of newborn screening. Med. Genet. 2022, 34, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerjav Tansek, M.; Groselj, U.; Angelkova, N.; Anton, D.; Baric, I.; Djordjevic, M.; Grimci, L.; Ivanova, M.; Kadam, A.; Kotori, V.; et al. Phenylketonuria screening and management in southeastern Europe—Survey results from 11 countries. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2015, 10, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcù, E.; Postoli, E.; Cullufi, P.; Santoro, L.; Crisci, D.; Sidira, C.M.; Augoustides-Savvopoulou, P.; Skouma, A.; Grafakou, O. Newborn screening, diagnosis, and management of inherited metabolic disorders: Status and progress of the southern Mediterranean countries. JIM 2024, 1, e539. [Google Scholar]

- Health Resources and Services Administrated. Previously Nominated Conditions. 2025. Available online: https://www.hrsa.gov/advisory-committees/heritable-disorders (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health. Newborn Screening for Cytomegalovirus (CMV). Available online: https://www.wadsworth.org/sites/default/files/WebDoc/017286_20547_NewbornScreeningCMV_web_final.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Martin, M.M.; Wilson, R.; Caggana, M.; Orsini, J.J. The impact of post-analytical tools on New York screening for Krabbe disease and Pompe disease. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2020, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontag, M.K.; Miller, J.I.; McKasson, S.; Gaviglio, A.; Martiniano, S.L.; West, R.; Vazquez, M.; Ren, C.L.; Farrell, P.M.; McColley, S.A.; et al. Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis: A qualitative study of successes and challenges from universal screening in the United States. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2022, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.B., Jr.; Porter, K.A.; Andrews, S.M.; Raspa, M.; Gwaltney, A.Y.; Peay, H.L. Expert evaluation of strategies to modernize newborn screening in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2140998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, C.D.; Therrell, B.L., Jr.; Working Group of the Asia Pacific Society for Human Genetics on Consolidating Newborn Screening Efforts in the Asia Pacific Region. Consolidating newborn screening efforts in the Asia Pacific region: Networking and shared education. J. Community Genet. 2012, 3, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, N.; Hasegawa, Y.; Yamada, K.; Kobayashi, H.; Purevsuren, J.; Yang, Y.; Dung, V.C.; Khanh, N.N.; Verma, I.C.; BijarniaMahay, S.; et al. Diversity in the incidence and spectrum of organic acidemias, fatty acid oxidation disorders, and amino acid disorders in Asian countries: Selective screening vs. expanded newborn screening. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2018, 16, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiley, V.; Webster, D.; Loeber, G. Screening pathways through China, the Asia Pacific Region, the World. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2019, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajima, T. Newborn screening in Japan—2021. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2022, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasaki, K.; Minamitani, K.; Nakamura, A.; Kobayashi, H.; Numakura, C.; Itoh, M.; Mushimoto, Y.; Fujikura, K.; Fukushi, M.; Tajima, T. Guidelines for newborn screening of congenital hypothyroidism (2021 Revision). Clin. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2023, 32, 26–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, A.; Wada, Y.; Ohura, T.; Kure, S. The discovery of GALM deficiency (type IV galactosemia) and newborn screening system for galactosemia in Japan. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2021, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, Y.H.; Hwu, W.L.; Lee, N.C. Newborn screening: Taiwanese experience. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 7, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwu, W.L.; Chien, Y.H. Development of newborn screening for Pompe Disease. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2020, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.J.; Liao, H.C.; Gelb, M.H.; Chuang, C.K.; Liu, M.Y.; Chen, H.J.; Kao, S.M.; Lin, H.Y.; Huang, Y.H.; Kumar, A.B.; et al. Taiwan national newborn screening program by tandem mass spectrometry for mucopolysaccharidoses types I, II, and VI. J. Pediatr. 2019, 205, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S.C.; Chien, Y.H.; Chang, K.L.; Lee, C.; Hwu, W.L. The timely needs for infantile onset Pompe disease newborn screening-practice in Taiwan. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2020, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.C.; Chang, K.L.; In’t Groen, S.L.M.; de Faria, D.O.S.; Huang, H.J.; Pijnappel, W.W.M.P.; Hwu, W.L.; Chien, Y.H. Outcome of later-onset Pompe disease identified through newborn screening. J. Pediatr. 2022, 244, 139–147.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Chang, Y.H.; Lee, C.L.; Tu, Y.R.; Lo, Y.T.; Hung, P.W.; Niu, D.M.; Liu, M.Y.; Liu, H.Y.; Chen, H.J.; et al. Newborn screening program for mucopolysaccharidosis type II and long-term follow-up of the screen-positive subjects in Taiwan. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, Y.H.; Lee, N.C.; Chen, P.W.; Yeh, H.Y.; Gelb, M.H.; Chiu, P.C.; Chu, S.Y.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, A.R.; Hwu, W.L. Newborn screening for Morquio disease and other lysosomal storage diseases: Results from the 8-plex assay for 70,000 newborns. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2020, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajadurai, V.S.; Yip, W.Y.; Lim, J.S.C.; Khoo, P.C.; Tan, E.S.; Mahadev, A.; Joseph, R. Evolution and expansion of newborn screening programmes in Singapore. Singap. Med. J. 2021, 62, S26–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health, Government of Hong Kong. Document Number: NBSIEM/1-60-2/04. Newborn Screening Program for Inborn Errors of Metabolism. Available online: https://www.smartpatient.ha.org.hk/en/smart-patient-web/disease-management/disease-information/disease/NewbornScreeningProgramme (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Belaramani, K.M.; Chan, T.C.H.; Hau, E.W.L.; Yeung, M.C.W.; Kwok, A.M.K.; Lo, I.F.M.; Law, T.H.F.; Wu, H.; Wong, S.S.N.; Lam, S.W.; et al. Expanded Newborn Screening for Inborn Errors of Metabolism in Hong Kong: Results and Outcome of a 7 Year Journey. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2024, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aging Care. Newborn Bloodspot Screening. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/newborn-bloodspot-screening (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- O’Leary, P.; Maxwell, S. Newborn bloodspot screening policy framework for Australia. Australas. Med. J. 2015, 8, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metternick-Jones, S.C.; Lister, K.J.; Dawkins, H.J.; White, C.A.; Weeramanthri, T.S. Review of current international decisionmaking processes for newborn screening: Lessons for Australia. Front. Public Health 2015, 3, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, C.; Knoll, D.; de Hora, M.; Kyle, C.; Glamuzina, E.; Webster, D. The decision to discontinue screening for carnitine uptake disorder in New Zealand. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2019, 42, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heather, N.; de Hora, M.; Brothers, S.; Grainger, P.; Knoll, D.; Webster, D. Introducing newborn screening for severe combined immunodeficiency-the New Zealand experience. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2022, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hora, M.R.; Heather, N.L.; Patel, T.; Bresnahan, L.G.; Webster, D.; Hofman, P.L. Measurement of 17-hydroxyprogesterone by LC MSMS improves newborn screening for CAH due to 21-Hydroxylase deficiency in New Zealand. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2020, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Lin, C.H.; Yin, X.; Zhu, L.; Yang, J.; Shen, Y.; Yang, C.; Chen, X.; Hu, H.; Ma, Q.; et al. Newborn screening for spinal muscular atrophy in China using DNA mass spectrometry. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.L.; Xu, F.; Jiang, K.; Wang, Y.M.; Ji, W.; Zhuang, Y.P. Evaluation of a panel of very long-chain lysophosphatidylcholines and acylcarnitines for screening of X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy in China. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 503, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mookken, T. Universal implementation of newborn screening in India. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2020, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, J.; Roy, P.; Thomas, D.C.; Jhingan, G.; Singh, A.; Bijarnia-Mahay, S.; Verma, I.C. Newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency for improving health care in India. J. Pediatr. Intensive Care 2020, 9, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Octavius, G.S.; Daleni, V.A.; Sagala, Y.D.S. An insight into Indonesia’s challenges in implementing newborn screening programs and their future implications. Children 2023, 10, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Saini, A.; Gupta, P. Improving newborn screening in India: Disease gaps and quality control. Clin. Chim. Acta 2024, 557, 117881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrajo, G.J.C. Newborn screening in Latin America: A brief overview of the state of the art. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C Semin. Med. Genet. 2021, 187, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giugliani, R.; Castillo Taucher, S.; Hafez, S.; Oliveira, J.B.; Rico-Restrepo, M.; Rozenfeld, P.; Zarante, I.; Gonzaga-Jauregui, C. Opportunities and challenges for newborn screening and early diagnosis of rare diseases in Latin America. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1053559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomé-Hidalgo, M.; Campos, J.D.; de Miguel, Á.G. Exploring wealth-related inequalities in maternal and child health coverage in Latin America and the Caribbean. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubaski, F.; Sousa, I.; Amorim, T.; Pereira, D.; Trometer, J.; Souza, A.; Ranieri, E.; Polo, G.; Burlina, A.; Brusius-Facchin, A.C.; et al. Neonatal screening for MPS disorders in Latin America: A survey of pilot initiatives. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2020, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poloni, S.; Dos Santos, B.B.; Chiesa, A.; Specola, N.; Pereyra, M.; Saborío-Rocafort, M.; Salazar, M.F.; Leal-Witt, M.J.; Castro, G.; Peñaloza, F.; et al. Current practices and challenges in the diagnosis and management of PKU in Latin America: A multicenter survey. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, A.L.S.; Martins, A.M.; Ribeiro, E.M.; Specola, N.; Chiesa, A.; Vilela, D.; Jurecki, E.; Mesojedovas, D.; Schwartz, I.V.D. Burden of phenylketonuria in Latin American patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, A.T.; Betsabé Castellanos Gómez, B.C. Barriers and facilitators of knowledge use in the health care system in Mexico: The newborn screening programme. Innov. Dev. 2019, 9, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela-Amieva, M.; Belmont-Martínez, L.; Ibarra-González, I.; Fernández-Lainez, C. Institutional variability of neonatal screening in Mexico. Boletín Médico Hosp. Infant. México 2009, 66, 431–439. [Google Scholar]

- Kopacek, C.; de Castro, S.M.; Prado, M.J.; da Silva, C.M.; Beltrão, L.A.; Spritzer, P.M. Neonatal screening for congenital adrenal hyperplasia in Southern Brazil: A population based study with 108,409 infants. BMC Pediatr. 2017, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusbrasil. Legislação—Lei Nº 14.154, de 26 de Maio de 2021. Law Creating a National Newborn Screening Program. Available online: https://www.jusbrasil.com.br/legislacao/1218254408/lei-14154-21 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Pimentel dos Santos, H.; Bonini Domingos, C.R.; Simone Martins de Castro, S. Twenty years of neonatal screening for sickle cell disease in Brazil: The challenges of a continental country with high genetic heterogeneity. J. Inborn Errors Metab. Screen. 2021, 9, e20210002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, L.M.Z.; Magalhães, P.K.R.; Ciampo, I.R.L.D.; Sousa, M.L.B.; Fernandes, M.I.M.; Sawamura, R.; Bittar, R.R.; Molfetta, G.A.; Silva Júnior, W.A.D. The first five-year evaluation of cystic fibrosis neonatal screening program in São Paulo State, Brazil. Cad. Saúde Pública 2020, 36, e00049719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teper, A.; Smithuis, F.; Rodríguez, V.; Salvaggio, O.; Maccallini, G.; Aranda, C.; Lubovich, S.; Zaragoza, S.; García-Bournissen, F. Comparison between two newborn screening strategies for cystic fibrosis in Argentina: IRT/IRT versus IRT/PAP. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2021, 56, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera Antequera, D.; Montealegre Páez, A.L.; Bermúdez, A.; García Robles, R. Importancia de una propuesta para la implementación de un programa de tamizaje neonatal expandido en Colombia. Revolut. Med. 2019, 27, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Neonatal Screening Is a Transcendental Measure of Equity in Colombia: President Duque. Press Release, 14 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shawky, R.M. Newborn screening in the Middle East and North Africa—Challenges and recommendations. Hamdan Med. J. 2012, 5, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrinska, V.; Khneisser, I.; Schielen, P.; Loeber, G. Introducing and expanding newborn screening in the MENA Region. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2020, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krotoski, D.; Namaste, S.; Raouf, R.K.; El Nekhely, I.; Hindi-Alexander, M.; Engelson, G.; Hanson, J.W.; Howell, R.R.; MENA NBS Steering Committee. Conference report: Second conference of the Middle East and North Africa newborn screening initiative: Partnerships for sustainable newborn screening infrastructure and research opportunities. Genet. Med. 2009, 11, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, R.E.; Op’t Hof, J.; Hitzeroth, H.W. Neonatal screening for congenital hypothyroidism. A decade’s review, including South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 1988, 73, 339–343. [Google Scholar]

- Hitzeroth, H.W.; Niehaus, C.E.; Brill, D.C. Phenylketonuria in South Africa. A report on the status quo. S. Afr. Med. J. 1995, 85, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ezenwosu, O.U.; Itanyi, I.U.; Nnodu, O.E.; Ogidi, A.G.; Mgbeahurike, F.; Ezeanolue, E.E. Community based screening for sickle haemoglobin among pregnant women in Benue State, Nigeria: I-Care-to-Know, A Healthy Beginning initiative. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, O.A.; Chen, C.S.; Brown, B.J.; Cursio, J.F.; Falusi, A.G.; Olopade, O.I. Knowledge and health beliefs assessment of Sickle cell disease as a prelude to neonatal screening in Ibadan, Nigeria. J. Glob. Health Rep. 2019, 3, e2019062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.A.; El-Mougy, F.; Sharaf, S.A.; Mandour, I.; Morgan, M.F.; Selim, L.A.; Hassan, S.A.; Salem, F.; Oraby, A.; Girgis, M.Y.; et al. Inborn errors of metabolism detectable by tandem mass spectrometry in Egypt: The first newborn screening pilot study. J. Med. Screen. 2016, 23, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotb, M.A.; Mansour, L.; William Shaker Basanti, C.; El Garf, W.; Ali, G.I.Z.; Mostafa El Sorogy, S.T.; Kamel, I.E.M.; Kamal, N.M. Pilot study of classic galactosemia: Neurodevelopmental impact and other complications urge neonatal screening in Egypt. J. Adv. Res. 2018, 12, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, R.A. The Human Genome Project changed everything. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020, 21, 575–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akintunde, O.; Tucker, T.; Carabetta, V.J. The Evolution of Next-Generation Sequencing Technologies. In High Throughput Gene Screening: Methods and Protocols; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Volume 2866, pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, T.; Chitnis, N.; Monos, D.; Dinh, A. Next-generation sequencing technologies: An overview. Hum. Immunol. 2021, 82, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Z.; Dolman, L.; Manolio, T.A.; Ozenberger, B.; Hill, S.L.; Caulfield, M.J.; Levy, Y.; Glazer, D.; Wilson, J.; Lawler, M.; et al. Integrating Genomics into Healthcare: A Global Responsibility. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 104, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, A.; Chung, W.K. Universal newborn screening using genome sequencing: Early experience from the GUARDIAN study. Pediatr. Res. 2024, 97, 1315–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillner, S.; Gumus, G.; Gross, E.; Iskrov, G.; Raycheva, R.; Stefanov, G.; Stefanov, R.; Chalandon, A.S.; Granados, A.; Nam, J.; et al. The modernisation of newborn screening as a pan-European challenge—An international delphi study. Health Policy 2024, 149, 105162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L. Integrating Newborn Genetic Screening with Traditional Screening to Improve Newborn Screening. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2025, 38, 2583588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, D.; Quarello, P.; Porta, F.; Cagnazzo, C.; Zucchetti, G.; Proto, C.F.; Gianasso, R.; Biamino, E.; Carbonara, C.; Coscia, A.; et al. A Genomic Sequencing Approach to Newborn Mass Screening and Its Opportunities. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2538198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genomic newborn screening: Current concerns and challenges. Lancet 2023, 402, 265. [CrossRef]

- Furlow, B. Newborn genome screening in the USA: Early steps on a challenging path. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2023, 7, 231–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.; Koval-Burt, C.; Kay, D.M.; Suchy, S.F.; Begtrup, A.; Langley, K.G.; Hernan, R.; Amendola, L.M.; Boyd, B.M.; Bradley, J.; et al. Expanded Newborn Screening Using Genome Sequencing for Early Actionable Conditions. JAMA 2025, 333, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genomics England. The Generation Study: Exploring Genome Sequencing in Newborns; Genomics England: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.genomicsengland.co.uk/initiatives/newborns (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Garnier, N.; Berghout, J.; Zygmunt, A.; Vreugdenhil, K.; Barisic, A.; Baban, A.; Barron, J.; Bejerano, G.; Bellettato, C.M.; Boccia, S. Genetic newborn screening and digital technologies: A project protocol based on a dual approach to shorten the rare diseases diagnostic path in Europe (Screen4Care). PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0295250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreugdenhil, K.; Zygmunt, A.; Lantos, J.D.; Prosser, L.A.; WES-NBS Study Group; Goldenberg, A.J. Ethics, Legal, and Social Implications (ELSI) of genetic newborn screening: An exploration of stakeholder perspectives across European countries—The Screen4Care project. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2024, 142, 107936. [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI). BabyScreen+: The Study; MCRI: Melbourne, Australia, 2024; Available online: https://www.mcri.edu.au/research/projects/babyscreen (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Institut de Pathologie et de Génétique (IPG). BabyDetect: Dépistage Néonatal par Séquençage Génétique; IPG: Gosselies, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://www.babydetect.be (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Zhou, W.; Zhang, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Lin, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, N.; Zong, F.; et al. Protocol of the China Neonatal Genomes Project: An observational study about genetic diseases screening in Chinese newborns. Pediatr. Med. 2021, 4, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.; Zhou, W. The China Neonatal Genomes Project (CNGP): New Advances in the Cohort Study of Genotype and Phenotype of Rare Diseases. J. Rare Dis. 2024, 3, 280–287. [Google Scholar]

- Remec, Ž.; Trebušak Podkrajšek, K.; Repič Lampret, B.; Kovač, J.; Groselj, U.; Tesovnik, T.; Battelino, T. Next-generation sequencing in newborn screening: A review of current state. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 662254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Screen4Care Consortium. Screen4Care: Accelerating Rare Disease Diagnosis. 2024. Available online: https://screen4care.eu (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Burlina, A.B.; Frazzini, G.; In ‘t Groen, S.L.M.; Krivák, R.; La Marca, G.; Scarpa, M.; van den Hout, J.M.P.; Pijnappel, W.W.M.P.; Reuser, A.J.J.; van der Ploeg, A.T. TREAT: Systematic and inclusive selection process of genes for genomic newborn screening as part of the Screen4Care project. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2024, 19, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondazione Giannino Bassetti; Consiglio Regionale della Lombardia. Progetto RINGS: Toward a Responsible Implementation of Genomic Newborn Screening; Fondazione Bassetti: Milano, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://www.fondazionetelethon.it/storie-e-news/news/dalla-ricerca/screening-genomico-neonatale-fondazione-telethon-e-regione-lombardia-annunciano-i-risultati-del-progetto-rings/ (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Regione Puglia. Legge Regionale 29 dicembre 2023, n. 37—Disposizioni per la formazione del bilancio di previsione 2024 e bilancio pluriennale 2024–2026. Boll. Uff. Della Reg. Puglia 2023, 113, 34, Programma “Genoma Puglia”. Available online: https://burp.regione.puglia.it (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Charli, J.; Michelle, A.F.; Sarah, N.; Kaustuv, B.; Bruce, B.; Ainsley, J.N.; Louise, H.; Nicole, M.; Didu, S.K. The Australian landscape of newborn screening in the genomics era. Rare Dis. Orphan Drugs J. 2023, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.J.; Mangwiro, Y.; Wake, M.; Saffery, R.; Greaves, R.F. Multi-omics analysis from archival neonatal dried blood spots: Limitations and opportunities. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2022, 60, 1318–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashenden, A.J.; Chowdhury, A.; Anastasi, L.T.; Lam, K.; Rozek, T.; Ranieri, E.; Siu, C.W.; King, J.; Mas, E.; Kassahn, K.S. The Multi-Omic Approach to Newborn Screening: Opportunities and Challenges. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2024, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerkhofs, M.H.P.M.; Haijes, H.A.; Willemsen, A.M.; van Gassen, K.L.I.; van der Ham, M.; Gerrits, J.; de Sain-van der Velden, M.G.M.; Prinsen, H.C.M.T.; van Deutekom, H.W.M.; van Hasselt, P.M.; et al. Cross-Omics: Integrating Genomics with Metabolomics in Clinical Diagnostics. Metabolites 2020, 10, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.S.; Pereira, C.; Aanicai, R.; Schröder, S.; Bochinski, T.; Kaune, A.; Urzi, A.; Spohr, T.; Viceconte, N.; Oppermann, S.; et al. An integrated multiomic approach as an excellent tool for the diagnosis of metabolic diseases: Our first 3720 patients. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2022, 30, 1029–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Li, P.; Hu, J.; Lin, Y.; Chen, Z.; Sun, L.; Wang, J.; et al. Integrated Metabolomic and Genomic Screening for Inborn Errors of Metabolism in a Large Cohort. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, e192534. [Google Scholar]

- Fecarotta, S.; Vaccaro, L.; Verde, A.; Alagia, M.; Rossi, A.; Colantuono, C.; Cacciapuoti, M.T.; Annunziata, P.; Riccardo, S.; Grimaldi, A.; et al. Combined biochemical profiling and DNA sequencing in the expanded newborn screening for inherited metabolic diseases: The experience in an Italian reference center. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2025, 20, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Q. Evaluating a Novel Newborn Screening Methodology: Combined Genetic and Biochemical Screenings. Arch. Med. Res. 2024, 55, 102959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Fan, C.; Huang, Y.; Feng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, J.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, C.; Jin, W.; et al. Genomic Sequencing as a First-Tier Screening Test and Outcomes of Newborn Screening. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2331162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, G.; Sharo, A.G.; Koleske, M.L.; Brown, J.E.H.; Norstad, M.; Adhikari, A.N.; Wang, S.; Brenner, S.E.; Halpern, J.; Koenig, B.A.; et al. Opportunities and challenges for the computational interpretation of rare variation in clinically important genes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 108, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman, T.S.; Crowley, S.B.; Roche, M.I.; Foreman, A.K.M.; O’Daniel, J.M.; Seifert, B.A.; Lee, K.; Brandt, A.; Gustafson, C.; DeCristo, D.M.; et al. Genomic Sequencing for Newborn Screening: Results of the NC NEXUS Project. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 107, 596–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilov, D.K.; Piazza, J.; Saltzman, J.; Zakaria, S.; Sanchez-Valle, A.; Oglesbee, D.; Raymond, K.; Rinaldo, P.; Tortorelli, S.; Matern, D. The Combined Impact of CLIR Post-Analytical Tools and Second Tier Testing on the Performance of Newborn Screening for Disorders of Propionate, Methionine, and Cobalamin Metabolism. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2020, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsmore, S.F.; Smith, L.D.; Kunard, C.M.; Bainbridge, M.; Batalov, S.; Benson, W.; Blocker, E.; Caylor, S.; Corbett, C.; Ding, Y.; et al. A genome sequencing system for universal newborn screening, diagnosis, and precision medicine for severe genetic diseases. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2022, 109, 1605–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, M.; Messina, G.; Casas, K.A.; Bellettato, C.M.; Lampe, C.; Campion, E.W.; Gevorkyan, A.; Dridi, L.; Brömmel, K.; Angastiniotis, M.; et al. Newborn Screening for Rare Diseases in Europe: Education and Awareness. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2022, 8, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Patti, G.J.; Yanes, O.; Siuzdak, G. Metabolomics: The apogee of the omics trilogy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceyhan-Birsoy, O.; Murry, J.B.; Machini, K.; Lebo, M.S.; Yu, T.W.; Fayer, S.; Genetti, C.A.; Schwartz, T.S.; Agrawal, P.B.; Parad, R.B.; et al. Interpretation of Genomic Sequencing Results in Healthy and Ill Newborns: Results from the BabySeq Project. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 104, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, A.N.; Gallagher, R.C.; Wang, Y.; Currier, R.J.; Amatuni, G.; Bassaganyas, J.; Chen, F.; Feuchtbaum, L.; Frazier, D.M.; Kwok, P.Y.; et al. The NBSeq Project: A Whole-Exome Sequencing-Based System for Universal Newborn Screening and Diagnosis of Inherited Metabolic Diseases. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 107, 599–611. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, G.; Tang, Y.; Cowan, T.M.; Zhao, H.; Scharfe, C. Reducing false positives in newborn screening using machine learning. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2020, 6, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.A.; Pereira, S.; Grandori, A.; Cereda, A.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Bican, A.; Miotto, R.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Gelb, M.H. Artificial intelligence in newborn screening: A systematic review. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1158794. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, N.; Brlek, P.; Bulić, L.; Brenner, E.; Škaro, V.; Skelin, A.; Projić, P.; Shah, P.; Primorac, D. Genomic sequencing for newborn screening: Current perspectives and challenges. Croat. Med. J. 2024, 65, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tummolo, A.; Ponzi, E.; Simonetti, S.; Gentile, M. Integrating the Genomic Revolution into Newborn Screening: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Pediatr. Rep. 2026, 18, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric18010014

Tummolo A, Ponzi E, Simonetti S, Gentile M. Integrating the Genomic Revolution into Newborn Screening: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Pediatric Reports. 2026; 18(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric18010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleTummolo, Albina, Emanuela Ponzi, Simonetta Simonetti, and Mattia Gentile. 2026. "Integrating the Genomic Revolution into Newborn Screening: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives" Pediatric Reports 18, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric18010014

APA StyleTummolo, A., Ponzi, E., Simonetti, S., & Gentile, M. (2026). Integrating the Genomic Revolution into Newborn Screening: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Pediatric Reports, 18(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric18010014