Malignancy Ratio in Pediatric Patients with Hereditary Multiple Exostoses: True Association or Reporting Bias?

Abstract

1. Introduction

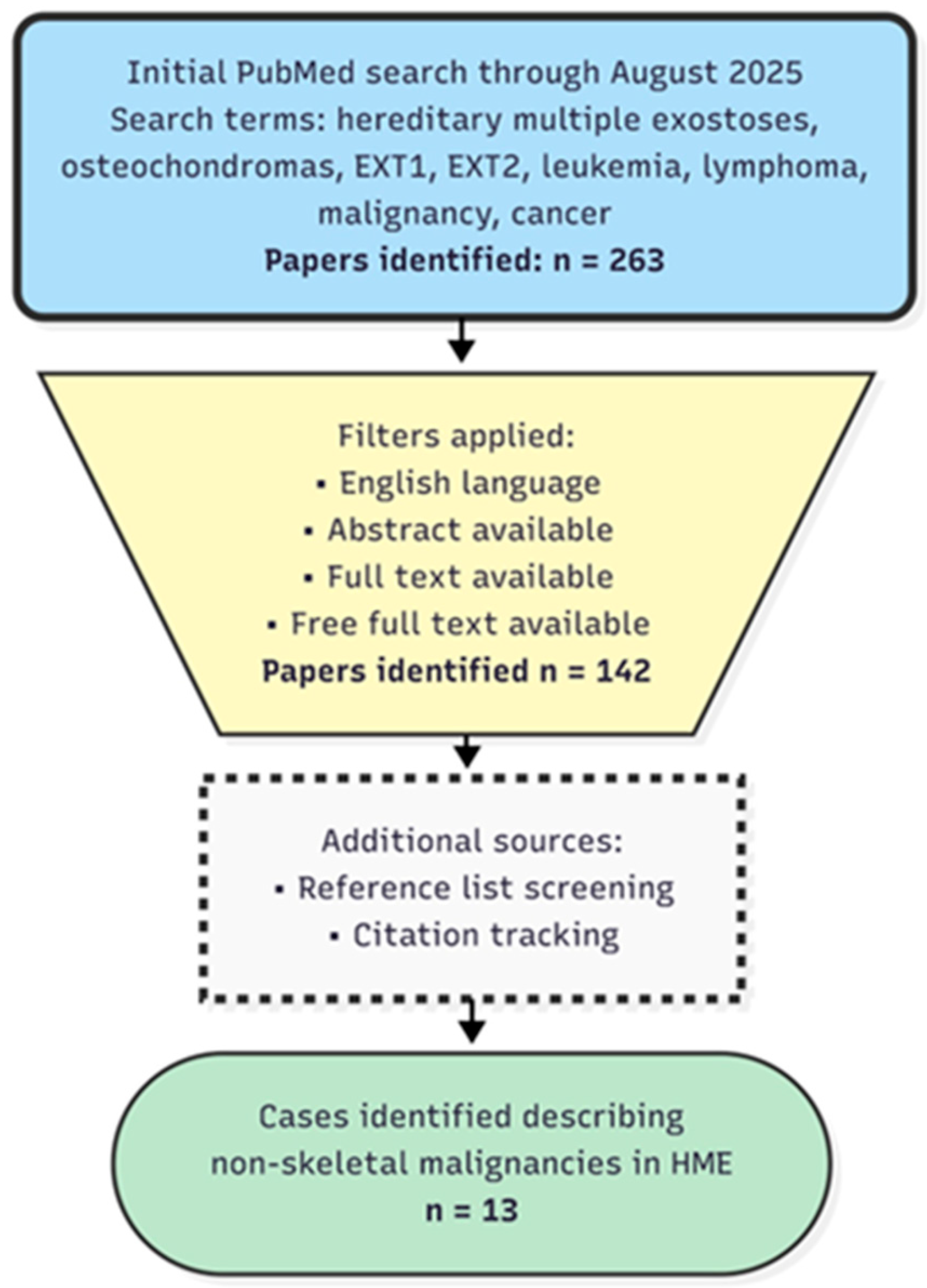

2. Materials and Methods

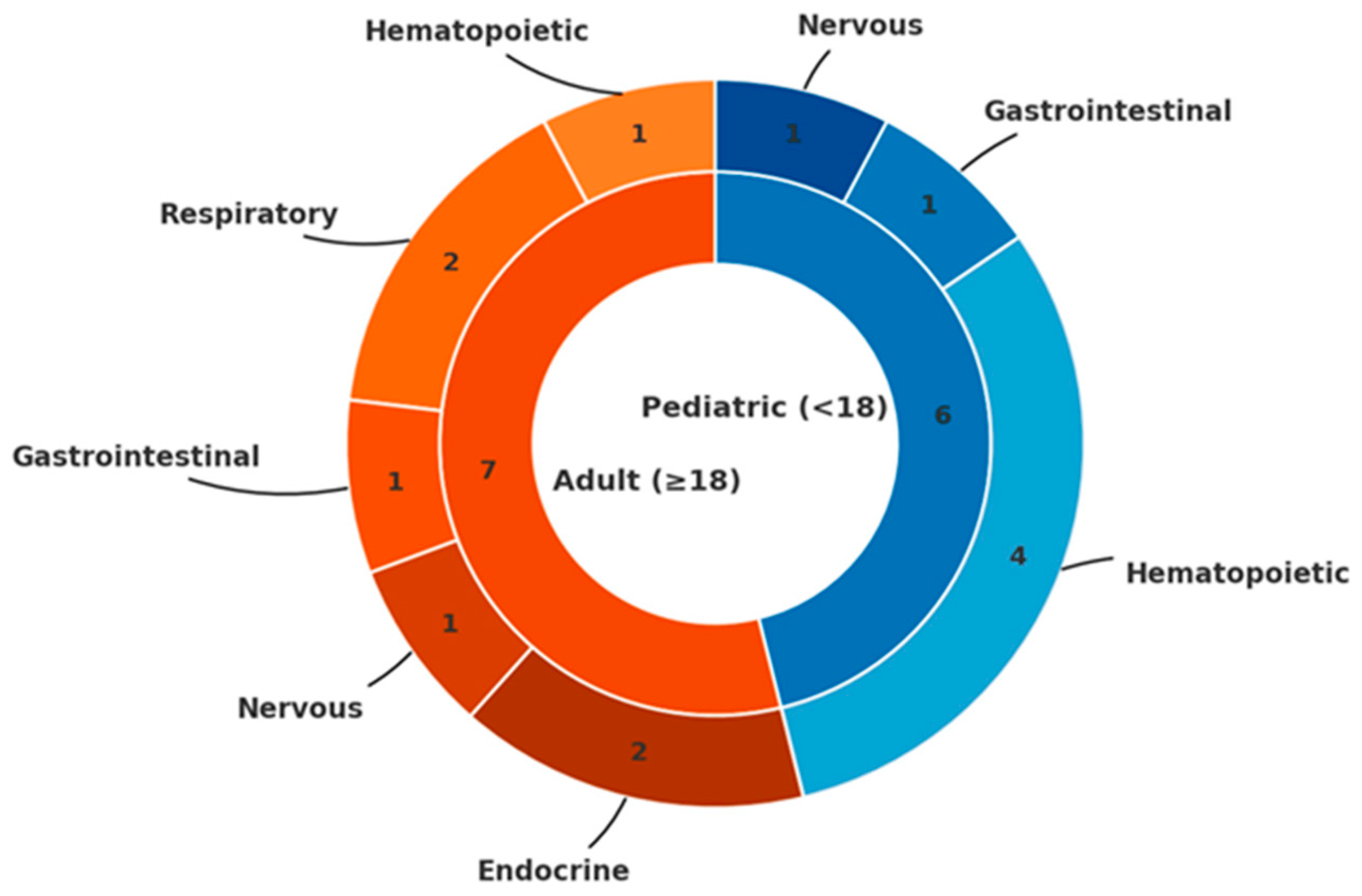

3. Results

3.1. Skeletal Malignancies

3.2. Hematologic Malignancies

3.3. Other Malignancies

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Francannet, C.; Cohen-Tanugi, A.; Le Merrer, M.; Munnich, A.; Bonaventure, J.; Legeai-Mallet, L. Genotype-phenotype correlation in hereditary multiple exostoses. J. Med. Genet. 2001, 38, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bovée, J.V.; Sakkers, R.J.; Geirnaerdt, M.J.; Taminiau, A.H.; Hogendoorn, P.C. Intermediate grade osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma arising in an osteochondroma. A case report of a patient with hereditary multiple exostoses. J. Clin. Pathol. 2002, 55, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ryckx, A.; Somers, J.F.; Allaert, L. Hereditary multiple exostosis. Acta Orthop. Belg. 2013, 79, 597–607. [Google Scholar]

- Wicklund, C.L.; Pauli, R.M.; Johnson, D.R.; Hecht, J.T. Natural history of hereditary multiple exostoses. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1995, 55, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmale, G.A.; Conrad, E.U.; Raskind, W.H. The natural history of hereditary multiple exostoses. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1994, 76, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanacci, M. Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors; Springer-Wien GmbH: Bologna, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, L. Hereditary multiple exostosis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 1963, 45-B, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, T.; Ichioka, Y.; Yagi, T.; Ishii, S. Spindle-cell sarcoma in patients who have osteochondromatosis. A report of two cases. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1988, 70, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krooth, R.S.; Maklin, M.T.; Hilsbish, T.S. Diaphyseal aclasis (multiple exostoses) on Guam. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1961, 13, 340–347. [Google Scholar]

- Stocks, P.; Barrington, A. Hereditary Disorders of Bone Development; Treasury of Human Inheritance; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 1925; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Terry Canale, S. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics; Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- D’Arienzo, A.; Andreani, L.; Sacchetti, F.; Colangeli, S.; Capanna, R. Hereditary Multiple Exostoses: Current Insights. Orthop. Res. Rev. 2019, 11, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrosi, R.; Ragone, V.; Caldarini, C.; Serra, N.; Usuelli, F.G.; Facchini, R.M. The impact of hereditary multiple exostoses on quality of life, satisfaction, global health status, and pain. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2017, 137, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ropero, S.; Setien, F.; Espada, J.; Fraga, M.F.; Herranz, M.; Asp, J.; Benassi, M.S.; Franchi, A.; Patiño, A.; Ward, L.S.; et al. Epigenetic loss of the familial tumor-suppressor gene exostosin-1 (EXT1) disrupts heparan sulfate synthesis in cancer cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004, 13, 2753–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cajiao, K.; Tomás, X.; Larqué, A.B.; Peris, P. Chondrosarcoma Transformation in Hereditary Multiple Exostosis: When to Suspect? Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 26, 2095–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishya, R.; Swami, S.; Vijay, V.; Vaish, A. Bilateral Total Hip Arthroplasty in a Young Man with Hereditary Multiple Exostoses. BMJ Case Rep. 2015, 2015, bcr2014207853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, D.E.; Lonie, L.; Fraser, M.; Dobson-Stone, C.; Porter, J.R.; Monaco, A.P.; Simpson, A.H. Severity of disease and risk of malignant change in hereditary multiple exostoses. A genotype-phenotype study. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2004, 86, 1041–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sønderskov, E.; Rölfing, J.D.; Baad-Hansen, T.; Møller-Madsen, B. Hereditary multiple exostoses. Ugeskr. Laeg. 2024, 186, V07240452. (In Danish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, L.; Ngoh, C.; Porter, D.E. Chondrosarcoma transformation in hereditary multiple exostoses: A systematic review and clinical and cost-effectiveness of a proposed screening model. J. Bone Oncol. 2018, 13, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rueda-de-Eusebio, A.; Gomez-Pena, S.; Moreno-Casado, M.J.; Marquina, G.; Arrazola, J.; Crespo-Rodríguez, A.M. Hereditary multiple exostoses: An educational review. Insights Imaging 2025, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ha, T.H.; Ha, T.M.T.; Nguyen Van, M.; Le, T.B.; Le, N.T.N.; Nguyen Thanh, T.; Ngo, D.H.A. Hereditary multiple exostoses: A case report and literature review. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep. 2022, 10, 2050313X221103732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Handa, T.; Asanuma, K.; Yuasa, H.; Nakamura, T.; Hagi, T.; Uchida, K.; Sudo, A. Osteosarcoma Arising from Iliac Bone Lesions of Hereditary Multiple Osteochondromas: A Case Report. Case Rep. Oncol. 2024, 17, 1266–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gözdaşoğlu, S.; Uysal, Z.; Kürekçi, A.E.; Akarsu, S.; Ertem, M.; Fitöz, S.; Ikincioğullari, A.; Cin, S. Hereditary multiple exostoses and acute myeloid leukemia: An unusual association. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2000, 17, 707–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakane, T.; Goi, K.; Oshiro, H.; Kobayashi, C.; Sato, H.; Kubota, T.; Sugita, K. Pre-B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a boy with hereditary multiple exostoses caused by EXT1 deletion. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2014, 31, 667–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comisi, F.; Fusco, C.; Mura, R.; Cerruto, C.; D’Agruma, L.; Carnazzo, S.; Castori, M.; Savasta, S. Hereditary Multiple Osteochondromas and Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Possible Role for EXT1 and EXT2 in Hematopoietic Malignancies. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2025, 18, e64052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neben, K.; Werner, M.; Bernd, L.; Ewerbeck, V.; Delling, G.; Ho, A.D. A man with hereditary exostoses and high-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the bone. Ann. Hematol. 2001, 80, 682–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince, S.D.; Krieger, P.A.; Walter, A.W. Burkitt Lymphoma in a Pediatric Patient with Hereditary Multiple Exostoses. Jefferson Digital Commons, Pediatric and Adolescent Cancer and Blood Diseases Faculty Papers. 2013. Available online: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1149&context=pacbfp (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Chudina, A.P.; Akulenko, L.V.; Prokopenko, V.D. Combination of multiple exostoses and lung cancer in 1 family. Vopr. Onkol. 1981, 27, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barbone, F.; Bovenzi, M.; Cavallieri, F.; Stanta, G. Cigarette smoking and histologic type of lung cancer in men. Chest 1997, 112, 1474–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.; Liu, Y.; Wu, C.; Wu, Z.; Ji, N.; Huang, M. Hereditary multiple exostoses complicated with lung cancer with cough as the first symptom: A case report. Transl. Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 3040–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pata, G.; Nascimbeni, R.; Di Lorenzo, D.; Gervasi, M.; Villanacci, V.; Salerni, B. Hereditary multiple exostoses and juvenile colon carcinoma: A case with a common genetic background? J. Surg. Oncol. 2009, 100, 520–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calas, R.A.R.; Millán, T.G.; Mohammed, S.; Leal, G.A.; Amadu, M.; Seidu, A.S. Advanced colon cancer coexisting with multiple Osteochondromatosis in a child; coincidence or causality?—A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2023, 108, 108427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Decker, R.E.; Wei, W.C. Thoracic cord compression from multiple hereditary exostoses associated with cerebellar astrocytoma. Case report. J. Neurosurg. 1969, 30, 310–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Xiao, B.O.; Li, L.I.; Feng, L.I. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor with hereditary multiple exostoses in an 18-year-old male: A case report. Oncol. Lett. 2015, 10, 1561–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Remde, H.; Kaminsky, E.; Werner, M.; Quinkler, M. A patient with novel mutations causing MEN1 and hereditary multiple osteochondroma. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. Case Rep. 2015, 2015, 14-0120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- I Numeri del Cancro in Italia. AIOM. Available online: https://www.aiom.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/2024_NDC-web.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49, Erratum in CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 203, https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisci, S.; Guzzinati, S.; Dal Maso, L.; Sacerdote, C.; Buzzoni, C.; Gigli, A.; AIRTUM Working Group. An estimate of the number of people in Italy living after a childhood cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 140, 2444–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| System | Pt | Malignancy | Age | Sex | Genetic Anomaly |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematopoietic | 1 | AML | 8 y | F | Not available |

| 2 | Pre-B ALL | 14 m | M | EXT1 deletion | |

| 3 | Pre-B ALL | 14 y | F | EXT2 mutation | |

| 4 | High grade NHL | 53 y | M | Not available | |

| 5 | BL (abdomen) | 10 y | M | Not available | |

| Respiratory | 6 | Lung SCC (uncertain correlation) | 56 y | M | Not available |

| 7 | Lung adenocarcinoma | 33 y | M | Not available | |

| Gastrointestinal | 8 | Colon carcinoma | 31 y | M | EXTL3 variant |

| 9 | Colorectal carcinoma | 12 y | M | Not available | |

| Nervous | 10 | Cerebellar astrocytoma | 15 y | M | Not available |

| 11 | Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor | 18 y | M | Not available | |

| Endocrine | 12 | Papillary thyroid carcinoma | 36 y | M | No EXT1/EXT2 alterations |

| 13 | MEN Type 1 | 47 y | M | EXT1 and MEN1 mutations |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Comisi, F.F.; Comisi, A.M.; Esposito, E.; Savasta, S. Malignancy Ratio in Pediatric Patients with Hereditary Multiple Exostoses: True Association or Reporting Bias? Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17060132

Comisi FF, Comisi AM, Esposito E, Savasta S. Malignancy Ratio in Pediatric Patients with Hereditary Multiple Exostoses: True Association or Reporting Bias? Pediatric Reports. 2025; 17(6):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17060132

Chicago/Turabian StyleComisi, Francesco Fabrizio, Andrea Maria Comisi, Elena Esposito, and Salvatore Savasta. 2025. "Malignancy Ratio in Pediatric Patients with Hereditary Multiple Exostoses: True Association or Reporting Bias?" Pediatric Reports 17, no. 6: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17060132

APA StyleComisi, F. F., Comisi, A. M., Esposito, E., & Savasta, S. (2025). Malignancy Ratio in Pediatric Patients with Hereditary Multiple Exostoses: True Association or Reporting Bias? Pediatric Reports, 17(6), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17060132