Abstract

The confirmed cases with COVID-19 in children account for just 1% of the overall confirmed cases. Severe COVID-19 in children is rare. Case Presentation: Our patient was 16 years old with a severe case of COVID-19 and did not survive due to the presence of Granulomatosis with polyangiitis and being treated with immunosuppressive drugs. We used lopinavir, ritonavir, hydroxy chloroquine, intravenous immunoglobulin and continuous veno-venous hemodialysis for treatment. Conclusion: In this patient, an underlying disease and delayed admission to the hospital were two factors complicating his condition.

1. Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 started as an epidemic in Wuhan, China and caught world-wide attention as a pandemic in January 2020. Confirmed pediatric cases account for just 1% of total cases [1].

Severe COVID-19 infections in children are rare. To date, the largest review of children with COVID-19 included 2143 children in China. Only 112 (5.6%) of 2143 children infected presented with severe symptoms (defined as hypoxia) and 13 (0.6%) children developed respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or multi-organ failure [2].

Our patient had a severe case of COVID-19 and did not survive due to the presence of Granulomatosis with polyangiitis and being treated with immunosuppressive drugs.

Rheumatological diseases and inflammatory bowel disease are immune disorders that are associated with an increased risk of opportunistic and community-acquired infections such as respiratory virus infections. They are at risk of high mortality and co-morbidity [3].

For patients with rheumatic disease, there is little data to understand the real consequences of the infection. Pediatric rheumatologists are expected to play a supporting role in treatment of COVID-19, both as pediatricians treating infected children, and as rheumatologists taking care of their rheumatic patients, as well as offering their experience in the possible alternative use of immunomodulatory drugs [4].

2. Case Presentation

A 16 year-old, 80-kg patient was referred to a tertiary hospital in Shiraz, Iran on 27 March 2020. He had a known case of Granulomatosis with polyangiitis and was diagnosed 2 years prior. At that time the patient presented with headache, sore throat, conjunctivitis for 1 month that was followed by lower extremities edema and joints pain and skin rash, and the Granulomatosis with polyangiitis was distinguished. His condition was in remission according to the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score for Wegener’s Granulomatosis Evaluation Form [5] before recent disease. The patient was on these medications before admission: prednisolone 10 milligrams (mg) daily, mycophenolate 360 mg twice per day, aspirin 80 mg daily, valsartan 10 mg daily, allopurinol 100 mg daily and folic acid. The patient’s complaint started with coughing and rhinorrhea 7 days prior to admission. His condition worsened over the following few days. He had very limited activity in the 3 days prior to admission. He displayed shortness of breath and preferred to lie down in a prone position.

On the day of admission, he was intubated in the emergency room due to respiratory distress and decreased O2 Saturation (O2 Sat) of 70%. He was transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). In the PICU, a ventilator was set up on SIMV with a respiratory rate of 20/min, tidal volume of 500 mL, inspiratory time: 1min, peak end expiratory pressure (PEEP): 15 cm H2O and FIO2: 100%. An infusion of norepinephrine was administered due to hypotension. Covid-19 RT-PCR came back positive. There was no history of exposure to confirmed or suspected coronavirus cases.

His medication continued except valsartan. Prednisolone changed to stress dose of hydrocortisone.

Lopinavir, ritonavir, hydroxy chloroquine, vancomycin and meropenem started. He also received intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) the first day of admission because of his refractory shock.

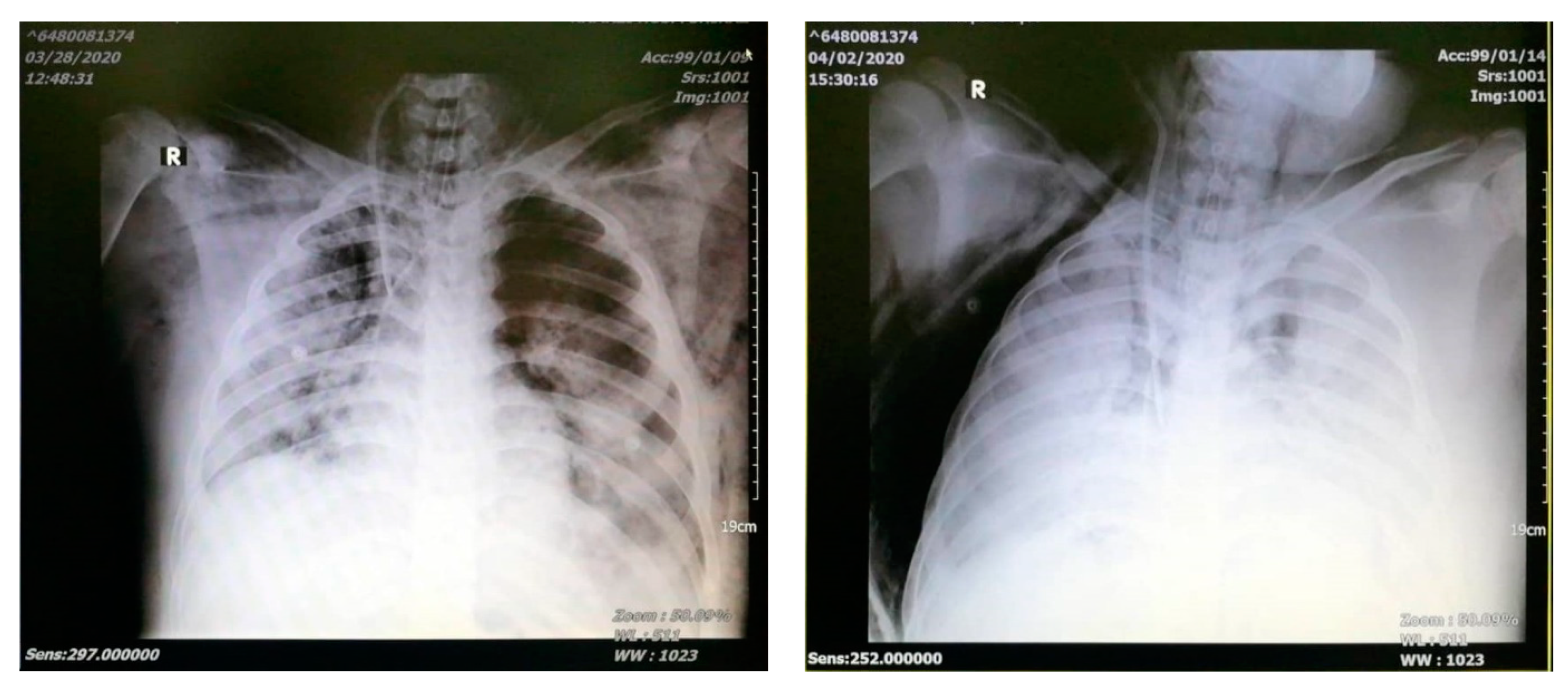

Chest X-ray on admission showed bilateral patchy infiltration which deteriorated to white lung on day 6 (Figure 1). A CT scan was not done due to his severe condition and the lack of a portable ventilator with high PEEP set up. All lab tests are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray on day 1 (left) and day 4 (right).

Table 1.

Lab tests from day 1 to day 6 of admission.

On day 3 he had atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. After emergency intervention, flecainide began with pediatric cardiologist consultation.

He also became anuric on day 4 and continuous veno-venous hemodialysis started for him. His condition deteriorated over time with a decrease in O2 Sat in spite of 100% of FIO2 and an increase in PEEP to 22cm H2O. On day 3, he was put into a prone positioning which helped to increase O2 Sat (up to 97%). However, it started to decline again after 36 h.

Unfortunately, the patient expired on day 6 of admission with low O2 Sat and bradycardia.

3. Discussion

COVID-19 mortality in children is very rare. The data from a low number of children suggest that even children who are on immunosuppressive treatment for various indications have a mild clinical course of COVID-19. Additionally, a study with eight children with inflammatory bowel disease (IBS), despite treatment with immunomodulators, biologics, or both, shows that all children diagnosed with COVID-19 had a mild infection [6].

But in this patient, an underlying disease and delayed admission to the hospital were two factors complicating his condition.

In addition, while there was extensive publicity for home quarantine, it is important to note that fears of contracting coronavirus may cause people to delay going to health centers until it is too late to treat them effectively. Some patients, concerned about over-burdening the healthcare system, may also delay seeking hospital treatment until their symptoms become critical.

The existing data on past and present coronavirus outbreaks show that immunosuppressed patients are not at increased risk of severe pulmonary disease compared with the general population. Children under the age of 12 years do not progress to severe coronavirus pneumonia, without paying attention to their immune status, although they get infected and can spread the infection [7].

Screening those who care for these high-risk patients is also suggested.

Author Contributions

A.S. and E.S. wrote the manuscript. E.S. gathered patient’s data and submitted the manuscript. Z.S. and S.A. edited the manuscript and were scientific consultant. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (IR.SUMS.MED.REC.1399.216).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents and sent to the ethics committee.

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yu, H.; Cai, Q.; Dai, X.; Liu, X.; Sun, H. The clinical and epidemiological features and hints of 82 confirmed COVID-19 pediatric cases aged 0–16 in Wuhan, China. MedRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, I.P.; Harwood, R.; Semple, M.G.; Hawcutt, D.B.; Thursfield, R.; Narayan, O.; Kenny, S.; Viner, R.; Hewer, S.L.; Southern, K.W. COVID-19 infection in children. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 446–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Marotto, D.; Antivalle, M.; Salaffi, F.; Atzeni, F.; Maconi, G.; Monteleone, G.; Rizzardini, G.; Antinori, S.; Galli, M.; et al. How to handle patients with autoimmune rheumatic and inflammatory bowel diseases in the COVID-19 era: An expert opinion. Autoimmun. Rev. 2020, 19, 102574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licciardi, F.; Giani, T.; Baldini, L.; Favalli, E.G.; Caporali, R.; Cimaz, R. COVID-19 and what pediatric rheumatologists should know: A review from a highly affected country. Pediatric Rheumatol. 2020, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, J.H.; Hoffman, G.S.; Merkel, P.A.; Min, Y.I.; Uhlfelder, M.L.; Hellmann, D.B.; Specks, U.; Allen, N.B.; Davis, J.C.; Spiera, R.F.; et al. A disease-specific activity index for Wegener’s granulomatosis: Modification of the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score. International Network for the Study of the Systemic Vasculitides (INSSYS). Arthritis Rheum 2001, 44, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlais, M.; Wlodkowski, T.; Vivarelli, M.; Pape, L.; Tönshoff, B.; Schaefer, F.; Tullus, K. The severity of COVID-19 in children on immunosuppressive medication. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, e17–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antiga, L. Coronaviruses and immunosuppressed patients: The facts during the third epidemic. Liver Transplant. 2020, 26, 832–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).